Key words

Caesalpinia pulcherrima, Fabaceae/Leguminosae, antimicrobial activity, antioxidant activity, physico-chemical analysis, phenols

Introduction

Caesalpinia pulcherrima (Fabaceae/Leguminosae) is a shrub or small tree up to 5 m height, commonly known as Guleture is distributed throughout India [1]. This shrub is one of the most popular summer bloomers. From May through August this tropical looking shrub produces loads of spectacular flower clusters. The plant is used as emmenagogue, purgative, stimulant and abortifacient, also used in bronchitis, asthma and malarial fever [2]. The fruit was used to check bleeding and prevent diarrhea and dysentery, while the flowers were utilized to combat oxidative stresses [3]. According to folkloric uses, the stem has been used as an abortifacient and an emmenagogue [4,5]. In traditional Indian medicine C. pulcherrima is used in the treatment of tridosha, fever, ulcer, abortifacient, emmenagogue, asthma, tumors, vata and skin diseases [6]. Antiviral, antiulcer, anti-inflammatory activity of different parts of C. pulcherrima has been reported [7-9].

The use of traditional medicine is widespread and plants still represent a large source of natural antioxidants that might serve as leads for the development of novel drugs [10]. Traditionally common people use crude extracts of plant parts as curative agents [11,12]. Plants are known to produce antimicrobial agents as their defense mechanism; they can be considered as potential sources of new antibacterial agents. A number of antibiotics and chemotherapeutic agents of natural or semi synthetic origins are available today to fight against infections caused by various pathogenic microorganisms [13].

In searching for novel natural antioxidants, some plants have been extensively studied in the past few years for their antioxidant and radical scavenging components [14,15] but there is still a demand to find more information concerning the antioxidant potential of plant species. Plant phenols are of interest because they are an important group of natural antioxidants and some of them are potent antimicrobial compounds [16]. DPPH (1, 1- diphenyl 2-picrylhydrazyl) has been used extensively as a free radical to evaluate reducing substances [17].

In view of the above considerations, it was thought of interest to investigate the antimicrobial and the antioxidant potential of Caesalpinia pulcherrima. The main goal of the present work was to assess the total phenolic and flavonoidal contents, antimicrobial activity, and antioxidant properties of various solvent extracts of the seed and fruits rind of C. pulcherrima.

Material and Methods

Plant collection

The fruits of Caesalpinia pulcherrima Swartz were collected in September, 2007 from Rajkot, Gujarat, India. The identification of this plant was done by Dr. N.K. Thakrar, of the Department of Biosciences, Saurashtra University, Rajkot, Gujarat, India, and kept under the Voucher specimen No. PSN246.

Plant extraction

The seeds and fruit rinds were separated and then washed under running tap water, air dried, homogenized to fine powder and stored in air-tight bottles. The powder of the seeds and fruits rind was extracted (10 g) successively with 100 ml each of n-hexane, chloroform, acetone, methanol and water with crude cold percolation extraction method. The extraction flasks were kept on a rotary shaker for 24 h at 120 rpm. Thereafter they were filtered through 8 layers of muslin cloth and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was concentrated to dryness under reduced pressure and stored at 4°C in air-tight bottles.

Qualitative Phytochemical analysis

The preliminary phytochemical analyses (Alkaloids, Flavonoids, Tannins, Phlobatannins, Triterpenes, Steroids, Saponins, and Cardiac glycosides) were performed according to the reported method [18].

Physico-chemical analysis

Physico-chemical analyses were carried out according to reported method in The Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India [19] and Vaghasiya et al. [20]. The following physico-chemical analyses; loss on drying at 105o C, total ash, water soluble ash, acid insoluble ash, Petroleum ether soluble extractive value, Ethanol soluble extractive value and Aqueous soluble extractive value were carried out.

Determination of the total phenolic content

The amount of the total phenolic content in the extracts of the different parts of C. pulcherrima was determined with Folin-Ciocalteu reagent method [21]. 0.5 ml sample (1 mg/ml) in 3 replicates and 0.1ml (0.5 N) Folin-Ciocalteu reagent were mixed and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Then, 2.5 ml saturated sodium carbonate was added and the resulting mixture was again incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance of the mixture was measured at 760 nm using spectrophotometer (Systronics: 106). The calibration curve was prepared using gallic acid (10 to 100 μg/ml) solution in distilled water. Total phenol values were expressed in terms of gallic acid (SRL, India) equivalent (mg/g of extracted compound).

Determination of the flavonoidal content

The flavonoidal content in the extracts of the different parts of C. pulcherrima was determined by Aluminum chloride colorimetric method [22]. 1.0 ml sample (1 mg/ml) in 3 replicates, 1.0 ml of methanol, 0.5 ml of (1.2 %) Aluminum chloride and 0.5 ml (120 mM) potassium acetate were mixed and the resulting mixture was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The absorbance of all the samples was measured at 415 nm using spectrophotometer (Systronics: 106). The calibration curve was prepared using quercetin (5 to 60 μg/ml) solution in methanol. The flavonoidal content was expressed in terms of quercetin (SRL, India) equivalent (mg/g of extracted compound).

DPPH• free radical scavenging assay

The free radical scavenging activity of various solvent extracts of C. pulcherrima was measured by using 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH) by the modified method of McCune and Johns [23]. The reaction mixture consisting of DPPH in methanol (0.3 mM, 1 ml) and different concentrations of the solvent extracts (1 ml) were incubated for 10 min. in dark, after which the absorbance was measured at 517 nm. Ascorbic acid (Hi Media, India) was used as positive control. The radical scavenging activity was expressed in terms of the amount of antioxidants necessary to decrease the initial DPPH absorbance by 50% (IC50).

% DPPH• radical scavenging = [(B – A) / B] × 100

Where B is the absorbance of the blank (DPPH• plus methanol) and A is the absorbance of the sample (DPPH• , methanol plus sample).

Antimicrobial Assay

Microorganisms tested

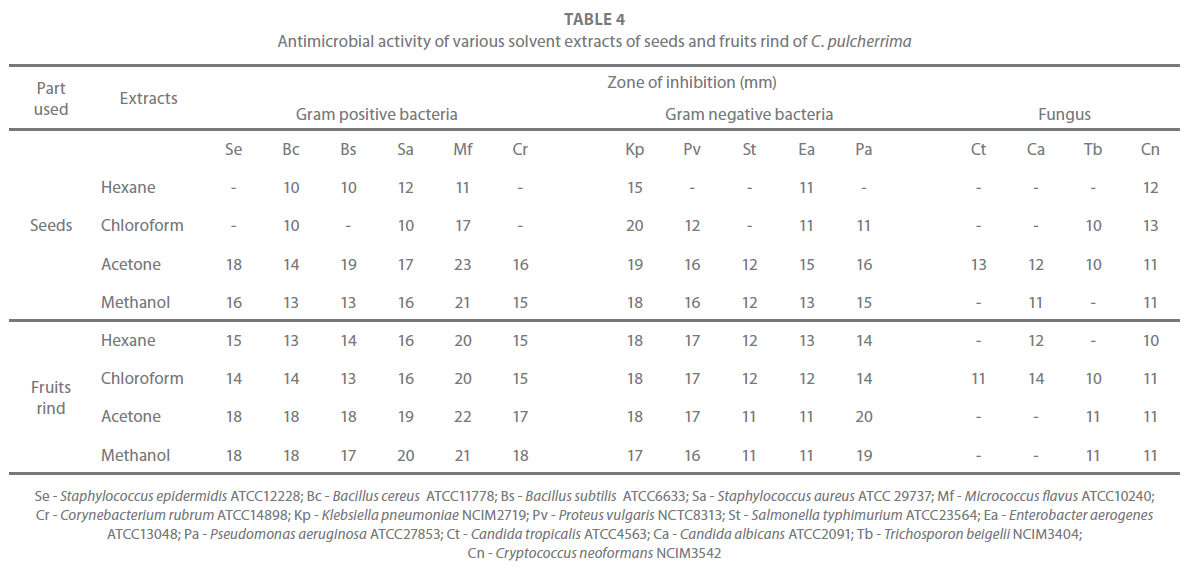

The microbial strains used to assess the antimicrobial properties included six Gram positive, five Gram negative and four fungal strains (Table 4). The investigated microbial strains were obtained from National Chemical Laboratory (NCL), Pune, India. The microorganisms were maintained on nutrient agar/MGYP (Hi Media, India) slope at 4o C and sub-cultured before use. The microorganisms are clinically important ones causing several infections and it is essential to overcome them through some active therapeutic agents.

Determination of the antimicrobial activity

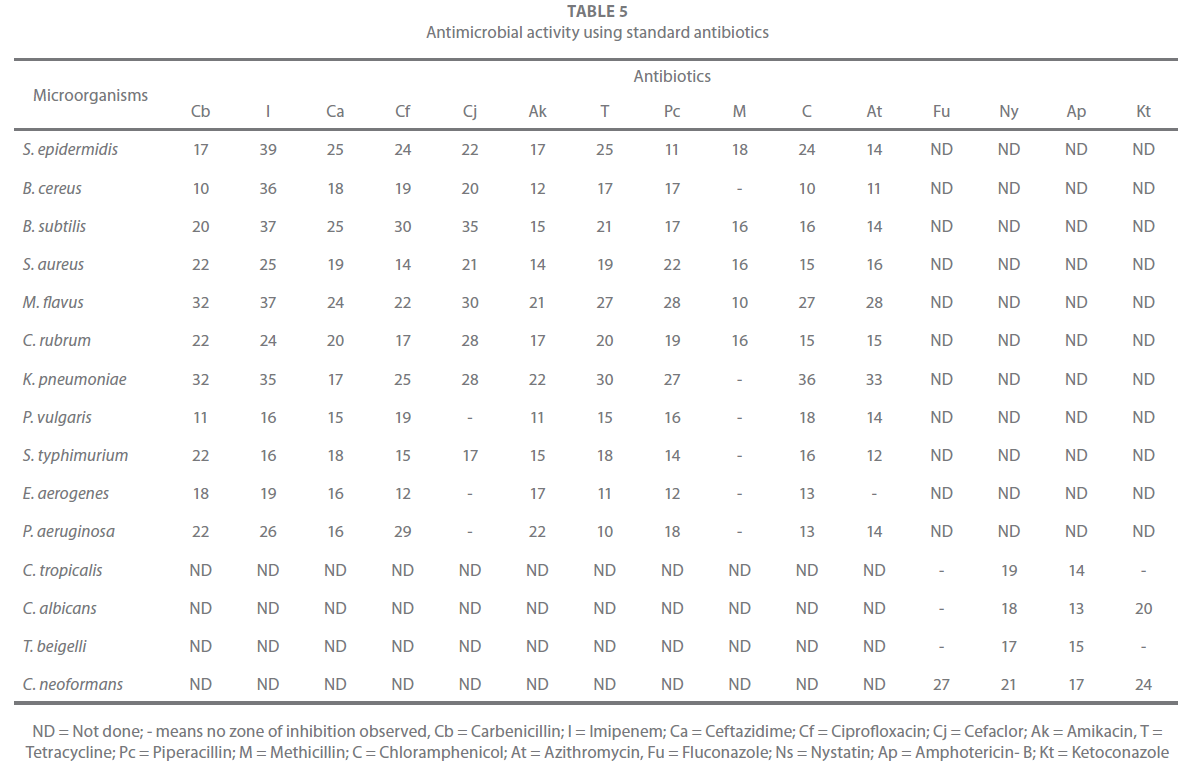

The antimicrobial assay of the extracts was carried out by agar well diffusion method [24,25]. The media used for bacteria was Muller Hinton agar no. 2 (Hi Media, India) and for fungi it was Sabaroud dextrose agar (Hi Media, India). The tested drug was diluted in 100% DMSO at a concentration of 25 mg/ml and the antimicrobial activity was evaluated at a concentration of 2.5 mg/well. The agar was melted and cooled to 48 – 50oC and a standard inoculum (1.5 x 108 cfu/ml, 0.5 McFarland) was then added aseptically to the molten agar and poured into sterile Petri dishes to give a solid plate. Wells were prepared in the seeded agar plates. Each tested compound (100 μl) was introduced in the well (8.5 mm). The plates were incubated at 37º C for bacteria and 28º C for fungi 24 h and 48 h respectively. The bacterial growth was determined by measuring the the diameter of inhibition zone. For each bacterial strain DMSO was used as negative control where pure solvents were used instead of the extract. The experiment was repeated three times to minimize the error and the mean values were presented. Commercial antibiotics (Hi Media, India) were used as positive control and were evaluated for their susceptibility against the microorganisms investigated. The antibiotics studied are given in Table 5.

Determination of the Minimum Inhibition Concentration (MIC)

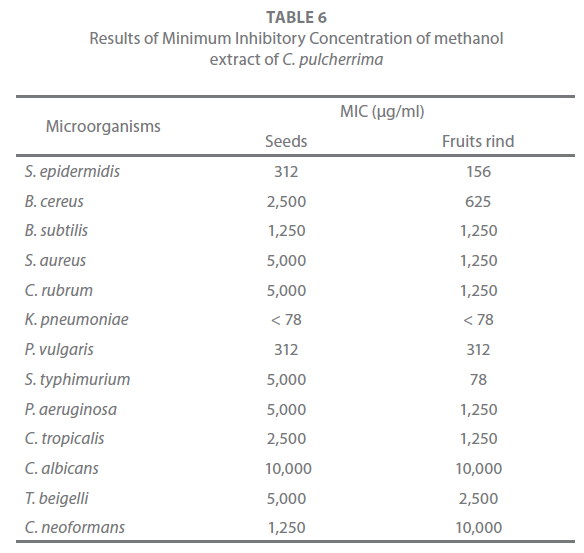

The end point MIC is the lowest concentration of compounds at which the tested microorganisms does not demonstrate visible growth. The broth tube dilution method utilizes relatively large amounts of the test agent and is not suitable for high throughput screening. Therefore, agar well diffusion method was used in the present study [26] to determine the MIC of the methanol extract of the different parts of Caesalpinia pulcherrima. The solution of the extract was 2-fold serially diluted in DMSO, in the range of 10,000 – 78 μg/ml. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration at which visible zone of inhibition was observed.

Results and Discussion

The presence of antibacterial substances in the higher plants is well established [27] and plants were also a good source for natural antioxidants [28]. Plants have provided a source of inspiration for novel drug compounds as plant derived medicines have made significant contribution towards human health. Phytomedicine can be used for the treatment of diseases caused by infectious diseases or those diseases caused by free radicals or it can be the base for the development of a medicine, a natural blueprint for the development of a drug.

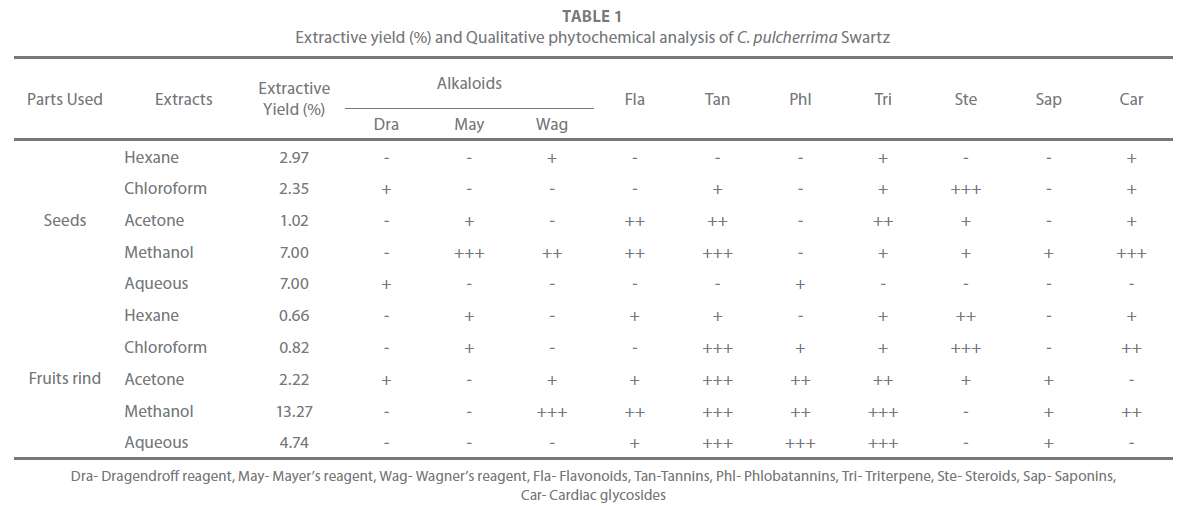

Extractive yield

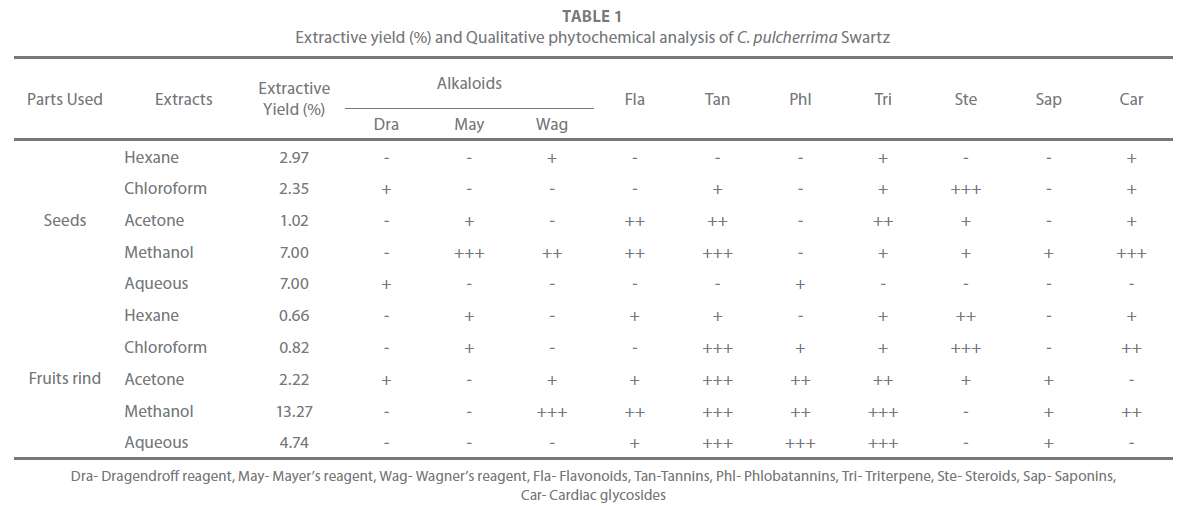

The extractive yield of the seeds and fruit rinds is given in Table 1. The extractive yield varied amongst the solvents used. In, both of the seeds and fruits rind, the methanol extracts showed highest extractive yield while the hexane and acetone extract of the fruits rind and the seeds respectively, showed minimum extractive yield. The extractive yield of the methanol extract of the fruits rind was 13.27% while that of the seeds was only 7%.

Table 1: Extractive yield (%) and Qualitative phytochemical analysis of C. pulcherrima Swartz

Phytochemical analysis

The hexane extract of the seeds showed only trace amount of triterpenes, cardiac glycosides and alkaloids (Wagner’s). The chloroform extract showed the presence of steroids and trace amount of tannins, triterpenes, cardiac glycosides and alkaloids (Dragendroff). The acetone extract showed the presence of flavonoids, tannins, triterpenes and trace amount of steroids, cardiac glycosides and alkaloids (Mayer’s) while the methanol extract exhibited the presence of all phytoconstituents except phlobatannins while the aqueous extract only contained phlobatannins and alkaloids (Dragendroff) in very trace amount. The hexane extract of the fruits rind showed the presence of flavonoids, tannins, triterpenes, cardiac glycosides, alkaloids (Mayer’s test) and steroids in very trace amount. Tannins, steroids, cardiac glycosides were present in the chloroform extract while phlobatannins, triterpenes and alkaloids (Mayer’s test) were present in very trace amount. The acetone extract showed the presence of all phytoconstituents except cardiac glycosides. The methanol extract showed the presence of all phytoconstituents except steroids (positive for Wagner’s test). Tannins, phlobatannins and triterpenes were present in aqueous extract while flavonoids and saponins were present in very trace amount (Table 1).

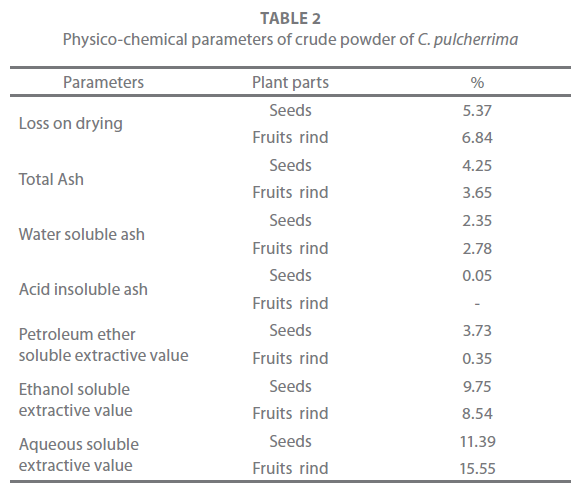

Physico-chemical analysis

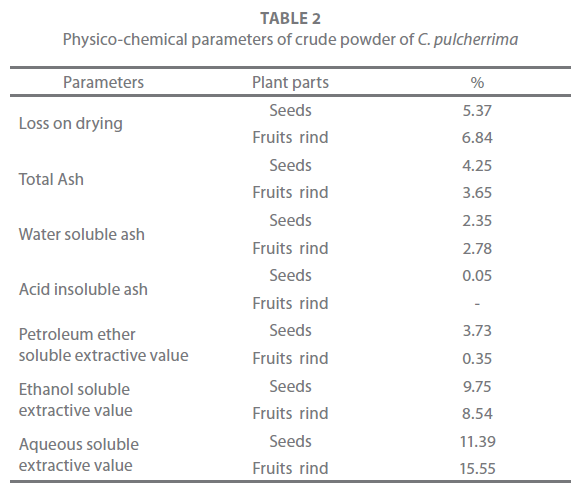

Physico-chemical (proximate) parameters may enhance the efficacy of the crude powder against various ailments. Crude powder of the seeds and fruits rind of C. pulcherrima was subjected to various proximate parameters, the results of which are shown in Table 2. The fruits rind had the highest value of loss on drying (6.84%) indicated more moisture content. Water soluble ash and aqueous soluble extractive value were also the maximum in fruits rind (15.55 %). While total ash, petroleum ether soluble extractive yield and ethanol soluble extractive yield were the maximum in the seeds. The acid insoluble ash value was almost absent.

Table 2: Physico-chemical parameters of crude powder of C. pulcherrima

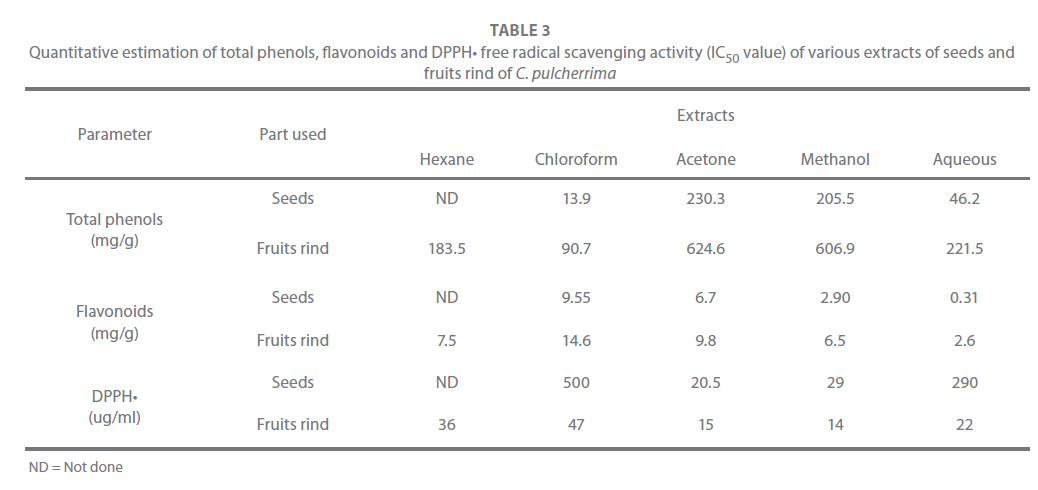

Total phenolic and flavonoidal content

The antioxidant activity of the phenolics is mainly due to their redox properties, which allow them to act as reducing agents, hydrogen donors and singlet oxygen quenchers. In addition, they have a metal chelating potential [29]. Flavonoids are a group of naturally occurring compounds widely distributed, as secondary metabolites in the plant kingdom. These flavonoids have been reported to possess antioxidant and antiradical properties [30].

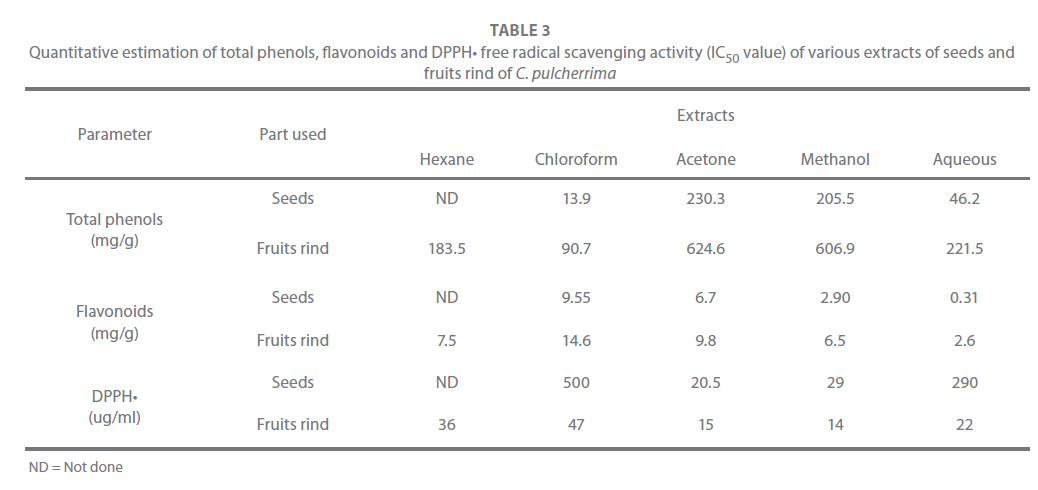

The total phenolic and flavonoidal content of the seeds and fruits rind are shown in Table 3, in which the extractive solvents of both parts revealed that, the total phenolic content was more than the flavonoidal content. Furthermore, the solvent extracts of the fruits rind had more phenolic content than that of the seeds; while the maximum content being in acetone extract, closely followed by methanol extract. The same trend was observed in the seeds extracts. The flavonoidal content also was more in the fruits rind as compared to that of the seeds, while maximum content being in the chloroform extract. A number of studies have focused on the biological activities of the phenolic compounds, which are the potential antioxidants and free radicalscavengers [29,31]. In the present study, the acetone and the methanol extracts contained the maximum amount of phenolics. Hence this may be a good source for phenolic compounds. Many studies have shown that natural antioxidants in plants are closely related to their biofunctionalities such as the reduction of chronic diseases and inhibition of pathogenic bacterial growth, which are often associated with the termination of free radical propagation in biological systems [32]. The phenolic compounds are also thought to contribute directly to the antioxidant activity. Yen et al. [33] and Duh et al. [34] suggested a correlation between phenolic content and antioxidant activity.

Table 3: Quantitative estimation of total phenols, flavonoids and DPPH• free radical scavenging activity (IC50 value) of various extracts of seeds and fruits rind of C. pulcherrima

DPPH• free radical scavenging activity

There are different methods for the estimation of the antioxidant activity. DPPH• free radical is commonly used as a substrate to evaluate the antioxidant activity; it is a stable free radical that can accept an electron or hydrogen radical to become a stable molecule. The DPPH• scavenging activity of the different solvent extracts of the seeds and fruit rind was different (Table 3). Comparing the five solvent extracts of the seeds and fruits rind, revealed that, the scavenging activity was more in the fruits rind than the seeds extract. The IC50 value of acetone and methanol extract of the fruits rind (IC50 value - 15 and 14 μg/ml respectively), was as good as that of the standard ascorbic acid (IC50 value - 11. 4 μg/ml); the other 3 extracts also showed a low IC50 values. In the seeds extracts, only the acetone and the methanol extracts showed a low IC50 values. The acetone and the methanol extracts of the fruits rind showed the maximum phenolic content and also a good antioxidant activity. It is also appeared that the extracts having more phenolics exhibited greatest antioxidant activity suggesting that the high scavenging activity may be due to hydroxyl groups existing in the phenolic compounds and the chemical structure that can provide the necessary component as a radical scavenger. Similar results were reported by Nuutila et al. [35], Yen et al. [33] and Saravana Kumar et al., [36].

Antimicrobial activity

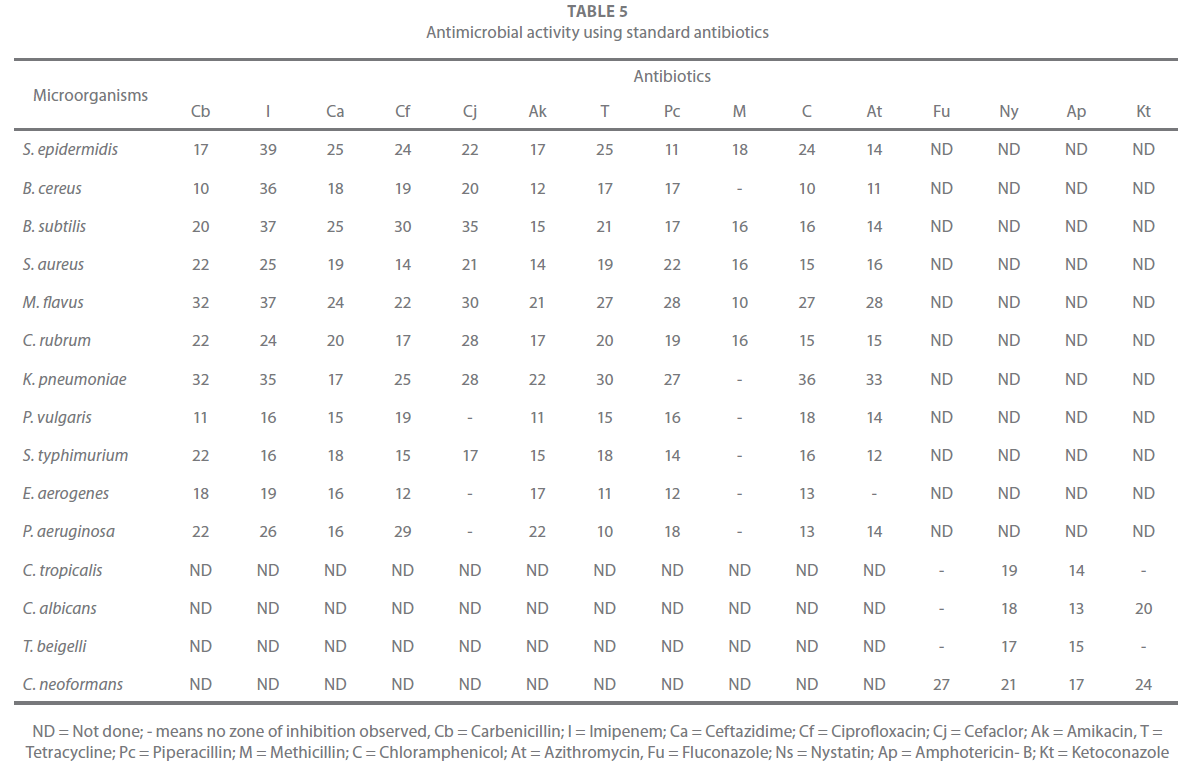

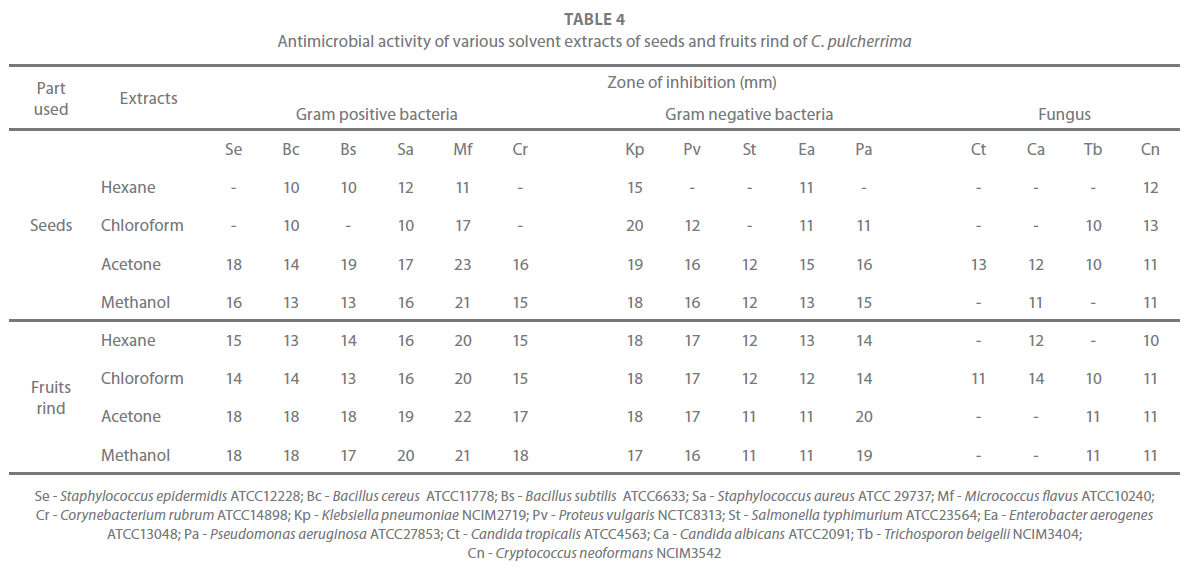

The antimicrobial activity of various solvent extracts of the seeds and the fruits rind of C. pulcherrima against six Gram positive, five Gram negative and four fungal strains are shown in Table 4 and the antimicrobial activity of these organism with different antibiotics is shown in Table 5. Amongst the four solvents, the acetone and the methanol extracts of both the seeds and the fruits rind showed better antimicrobial activity. The Gram positive bacteria were more susceptible than Gram negative bacteria. All the solvents extracts of both the seeds and the fruits rind showed a feeble anti-fungal activity. The most susceptible bacteria was M. flavus.

Table 4: Antimicrobial activity of various solvent extracts of seeds and fruits rind of C. pulcherrima

Table 5: Antimicrobial activity using standard antibiotics

From the above results, it can be stated that irrespective of the part and the solvent used, C. pulcherrima showed better antibacterial activity than antifungal activity. The antimicrobial activity of the fifteen studied strains against standard antibiotics is shown in Table 5. The antimicrobial activity of some of the solvent extracts was comparable with that of the standard antibiotics.

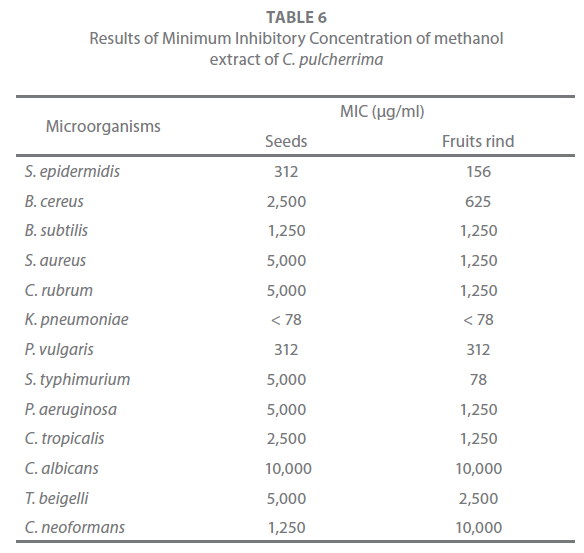

From the results of antimicrobial activity, the most active extract was subjected to the evaluation of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). The minimum inhibitory concentration of the methanol extract of the seeds and the fruits rind of C. pulcherrima is shown in Table 6. The MIC of C. pulcherrima ranged from 10,000 – 78 μg/ml. In the seeds and the fruits rind extracts, K. pneumoniae showed the least MIC value (< 78 μg/ml) while C. albicans showed MIC value > 10,000 μg/ml.

Table 6: Results of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of methanol extract of C. pulcherrima

Conclusion

Plant based antimicrobials have enormous therapeutic potential, they can serve the purpose without any side effects that are often associated with the synthetic antimicrobials. It is hoped that this study will lead to the establishment of some results, that could be used for further investigation to isolate the active compounds from the promising extracts, which could be used to formulate new and more potent antibacterial and antioxidant drugs from natural origin.

Acknowledgment

One of the authors Yogesh Baravalia is thankful to University Grants Commission, New Delhi, India for providing financial support as Junior Research Fellow.

273

References

- Pawar CR, Mutha RE, Landge AD, JadhavRB, SuranaSJ (2009) Antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of Caesalpiniapulcherrimawood. Indian J BiochemBiophys 46: 198-200.

- Pawar C, ShahareHV, BandalJN, Pal SC (2007) Antibacterial activity of heartwood of Caesalpiniapulcherrima. Indian J Nat Prod 23: 27.

- Ragasa CY, Hofilena JG, Rideout JA (2002) Newfuranoidditerpenes from Caesalpiniapulcherrima. J Nat Prod 65: 1107-1110.

- Patil AD, FreyerAJ, Webb RL, Zuber G, Reichwein R et al. (1997) Pulcherrimins A-D, novel diterpenedibenzoates from Caesalpiniapulcherrimawith selective activity against DNA repair- deficient yeast mutants. Tetrahedron 53:1583-1592.

- SrinivasKVNS, Rao YK, Mahender I, Das B, Rama Krishna KVS et al. (2003) Flavanoids from Caesalpiniapulcherrima. Phytochemistry 63: 789-793.

- Kirtikar KR, Basu BD (1935) Indian Medicinal Plants. Parts 1–3, L.M. Basu, Allahabad, India.

- Chiang LC, Chiang W, Liu MC, Lin CC (2003) In vitro antiviral activities of Caesalpiniapulcherrimaand its related flavonoids. J AntimicrobChemotherap 52: 194–198.

- Kumar A, Nirmala V (2004) Gastric antiulcer activity of the leaves of Caesalpiniapulcherrima. Indian J PharmaceuticSci 66: 676-678.

- Rao YK, Fang SH, TzengYM (2005) Anti-inflammatory activities of flavonoids isolated from Caesalpiniapulcherrima. J Ethnopharmacol 100: 249-253.

- Perry EK, Pickering AT, Wang WW, Houghton PJ, Perry NS (1999) Medicinal plants and Alzheimer’s disease: from ethnobotany to phytotherapy. J Pharm Pharmacol 51: 527-534.

- Mendoza L, Wilkens M, Urzua A (1997) Antimicrobial study of the resinous exudates and of diterpenoids and flavonoids isolated from some Chilean Pseudognaphalium(Asteraceae). J Ethnopharmacol 58: 85-88.

- Sanches NR, Cortez DAG, Schiavini MS, Nakamura CV, Filho BPD (2005) An evaluation of antibacterial activities of Psidiumguajava(L.). Brazilian Arch BiolTechnol 48: 429-436.

- Rahman MM, Gray AI, Khondkar P, Sarker SD (2008) Antibacterial and antifungal activities of the constituents of Flemingiapaniculata. PharmaceutBiol 46: 356-359.

- Mantle D, Eddeb F, Pickering AT (2000) Comparison of relative antioxidant activities of British medicinal plant species in vitro. J Ethnopharmacol 72: 47-51.

- OkeJM, Hamburger MO (2002) Screening of some Nigerian medicinal plants for antioxidant activity using 2, 2- diphenyl- picryl- hydrazyl radical.Afr J Biomed Res 5: 77-79.

- Chakraborty M, Mitra A (2008) The antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of the methanolic extract from Cocosnuciferamesocarp. Food Chem 107: 994-999.

- Cotelle N, BeminerJL, Catteau JP, Pommery J, Wallet JC et al. (1996) Antioxidant properties of hydroxyl flavones. Free Rad Biol Med 20: 35-43.

- Parekh J, Chanda S (2007a) Antibacterial and phytochemical studies on twelve species of Indian medicinal plants. Afr J Biomed Res 10: 175-181.

- The Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India (2008) Vol. VI, Government of India, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, department of Ayush, New Delhi.

- Vaghasiya Y, Nair R, Chanda S (2008) Antibacterial and preliminary phytochemical and physico-chemical analysis of Eucalyptus citriodoraHk leaf. Nat Prod Res 22: 754-762.

- McDonald S, PrenzlerPD, Antolovich M, Robards K (2001) Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of olive extracts. Food Chem 73: 73-84.

- Chang C, Yang M, Wen H, Chern J (2002) Estimation of total flavonoid content in propolis by two complementary colorimetric methods. J Food Drug Anal 10: 178-182.

- McCune LM, Johns T (2002) Antioxidant activity in medicinal plants associated with the symptoms of diabetes mellitus used by the indigenous peoples of the North American boreal forest. J Ethnopharmacol 82: 197-205.

- Perez C, Paul M, Bazerque P (1990) An antibiotic assay by the agar well diffusion method. ActaBiol Med Expt 15: 113-115.

- Parekh J, Chanda S (2007b) In vitro antibacterial activity of the crude methanol extract of WoodfordiafruticosaKurz. Flower (Lythraceae). Braz J Microbiol 38: 204-207.

- Habeeb F, Shakir E, Bradbury F, Cameron P, TaravatiMR et al. (2007) Screening methods used to determine the antimicrobial properties of Aloe verainner gel. Methods 42: 315-320.

- Srinivasan D, Nathan S, Suresh T, Perumalsamy O (2001) Antimicrobial activity of certain Indian medicinal plants used in folkloric medicine. J Ethnopharmacol 74: 217-220.

- Maisuthisakul P, Gordon MH (2009) Antioxidant and tyrosinase inhibitory of mango seed kernel by product. Food Chem 117: 332-341.

- Kahkonen MP, Hopia AI, VuorelaHJ, Rauha JP, Pihlaja K et al. (1999) Antioxidant activity of plant extracts containing phenolic compounds. J Agric Food Chem 47: 3954- 3962.

- Nakayama J, Yamada M (1995) Suppresion of active oxygen indeed cytotoxicity by flavonoids. BiochemPharmacol 45: 265-267.

- Sugihara N, Arakawa T, Ohnishi M, Furuno K (1999) Anti and prooxidative effects of flavonoids on metal induced lipid hydroperoxide dependent lipid peroxidation in cultured hepatocytes coaded with α-linolenic acid. Free Rad Biol Med 27: 1313-1323.

- Covacci V, Torsello A, Palozza P, Sgambato A, Romano G et al. (2001) DNA oxidative damage during differentiation of HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells. Chem Res Toxicol 14: 1492–1497.

- Yen GC, Duh PD, Tsai CL (1993) Relationship between antioxidant activity and maturity of peanut hulls. J Agric Food Chem 41: 67-70.

- Duh PD, TuYY, Yen GC (1999) Antioxidant activity of water extract of HarngJyur (Chrysanthemum morifoliumRamat). Leb-WisTechnol 32: 269-277.

- Nuutila AM, Puupponen-Pimia R, Aarni M, Oksman-Caldentery KM (2003) Comparison of antioxidant activities of onion and garlic extracts by inhibition of lipid peroxidation and radical scavenging activity. Food Chem 81: 485-493.

- Saravanakumar A, Mazumder A, Vanitha J, Venkateshwaran K, Kamalakannan K et al. (2008) Evaluation of antioxidant activity, phenol and flavonoid contents of some selected Indian medicinal plants. Phcog Mag 4: 143- 147.