Charles W. Denko1,Joanne D. Denko1, and Charles J. Malemud2*

1Division of Rheumatic Diseases at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH 44106-5076, USA

2Department of Medicine, University Hospitals Case Medical Center, USA

Corresponding Author:

Charles J. Malemud

Department of Medicine, Division of Rheumatic Diseases

University Hospitals Case Medical Center, 2061 Cornell Rd., Rm. 207 Cleveland

OH 44106-5076, USA

Tel: 2168447846

Fax: 2168442288

E-mail:cjm4@cwru.edu

Received date: December 03, 2015 Accepted date: January 07, 2016 Published date: January 14, 2016

Citation: Denko CW , Denko J, Malemud CJ , Artistic Evidence of Inflammatory Arthopathy from Ancient Scythia. Arch Med. 2015, 8:2.

Introduction

Evidence for the existence of inflammatory arthropathy, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), in antiquity is based mainly on studies of skeletal remains that are centuries old [1]. For example, in North America, RA was described in ancient times as long ago as 6500-4500 BCE based on the RA-like deformities found in skeletons unearthed from the Tennessee River and from bones believed to have been from around 1400-1550 that were recovered from skeletal remains in Mexico [1]. However, from a clinical perspective, the first clinical distinction between RA and the inflammatory arthopathy of gout was mentioned by Aceves- Avila et al. [2] to have existed in Mexico in 1578. Sir Benjamin Brodie (1817-1880) also clearly described an inflammatory arthritis which may have been reactive arthritis or RA [3]. By most accounts, the first accurate clinical description of RA is generally attributed to Augustin-Jacob Landre-Beauvais who in 1880 described a clinical condition that appeared to be most compatible with RA [4].

Undoubtedly, a clinical condition with inflammatory arthopathy-like characteristics existed well before the 19th century [5]. For example, the Roman Emperor Constantine seems to have had a condition now known as RA, although it was probably misdiagnosed as ‘rheumatism.’ According to an analysis of several paintings from the Flemish-Dutch school (1400-1700) which was reviewed by Dequeker [6], the appearance of hands were often portrayed as deformities in works of art from that period. Of note, the Dutch painter, Van Gogh, did not ignore features suggestive of RA in the female model who posed for him for “La Berceuse” which he completed in 1888 [7]. Notably, the esteemed artist, Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) also clearly suffered from RA [8].

The Scythian Empire

The Scythians were the first pastoral nomadic group from Central Asia. In the latter half of the 7th century BCE, the Scythians were allied with the Assyrians against the Medes, who were rising to power in northwestern Persia, and with the Cimmerians, a little known people who preceded the Scythians into southern Russia [9]. In his writings, the Greek historian Herotodus indicated that the Scythians ruled from the Dover River in present-day Southern Russia to the Carpathian Mountains in central Europe in the 5th century BCE. The Scythians remained in power until the Samaratians displaced them around the 2nd and 1st century BCE [9]. Because there is no record of a written Scythian language, much of what is known about their cultural activities stems from artistic renditions of everyday life.

Scythian Gold

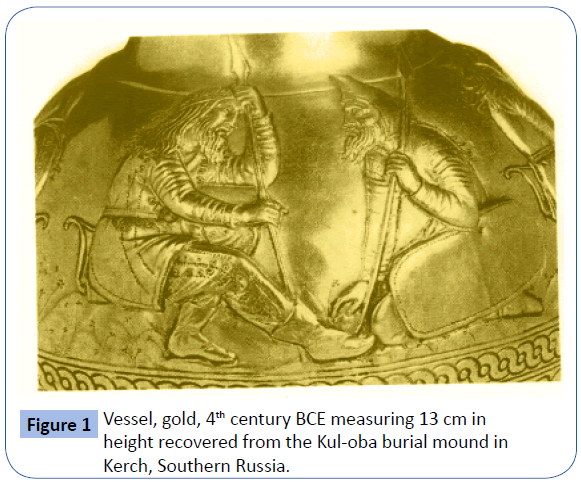

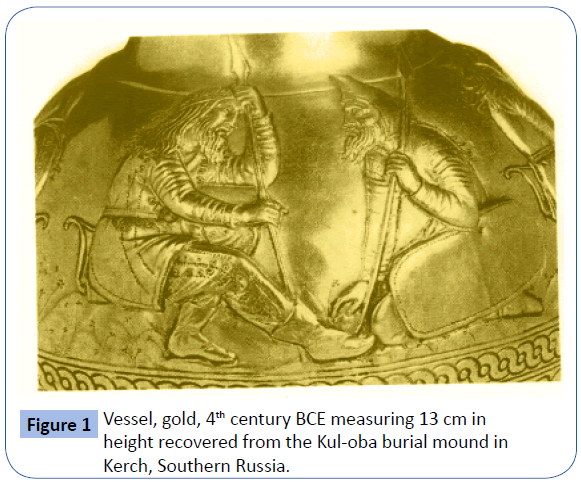

An unknown artist, working in gold, a common medium for Scythian goldsmiths created a pictorial panel (Figure 1) suggesting a patient in consultation with his physician 2500 years ago [10].

Figure 1: Vessel, gold, 4th century BCE measuring 13 cm in height recovered from the Kul-oba burial mound in Kerch, Southern Russia.

In the summer of 1983, Dr. Charles W. Denko (CWD) visited the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, which had been established by Czar Peter the Great. There an exhibit of Scythian gold artifacts was on display. A gold vessel (Figure 1) held a special interest for CWD because it appeared to depict an historical rendition of rheumatic diseases in antiquity that had been described by Hippocrates and Herodotus [11,12]. CWD suggested that the portrayal shown on this gold vessel represented inflammatory arthopathy in ancient Scythia. This view was sustained by Professor Valentina Nassonova who agreed in a correspondence with CWD (A communication between Charles W. Denko, PhD, MD and Professor Valentina Nassonova, MD, October 30, 1997) that the deformities depicted in the hand and foot appeared to be consistent with inflammatory arthopathy.

Based on photographs taken at the time of CWD’s visit to the Hermitage, the gold vessel (Figure 1) was measured at 13 cm in height. The vessel was said to have been recovered from the Kul-oba burial mound in the district called Kurgans near Kerch in Southern Russia. This region formed a part of the Crimean Peninsula where the vessel was believed to have been buried in the 4th century BCE. On the mid-portion of the vessel is a panel measuring about 8 cm × 10 cm depicting two Figures which fill most of the panel. We presume that the Figures on the viewer’s left is a patient with a swollen foot. We contend that the other Figures on the viewer’s right is a physician or shaman. Thus, the physical attributes depicted in the personage to the right could serve as a control subject for comparison to the patient on the left.

Demographic differences in societal status between the two Figures are suggested by both the clothing and furniture. Each of the individuals has a spear of the same size suggesting that the shaman probably also participated in battle as did the patient. Thus, the possibility that the person on the left is being examined for evidence of a wound sustained in battle must also be considered. The two persons are on the same level, eye to eye. The shaman appears to be kneeling while the patient appears to be sitting on a small chair. Behind the shaman is another large object but it is difficult to determine the exact character of this ornament. What may be a badge of office appears on the shaman’s blouse. The patient, however, wears a flat hat and his clothing is more highly decorated than the shaman’s garb suggesting that the patient was a prominent member of society. In addition, the patient wears trousers which appear more practical for riding horses than the tunic or toga more commonly found in other parts of Europe. The patient’s face appears to show an anguished expression suggestive of a painful condition whilst the shaman’s face appears unruffled, suggesting that he was accustomed to examining patients.

The patient’s right leg appears swollen at the knee, ankle and mid-foot. There is also some evidence of metatarsal swelling (Figure 1). Conversely, the left foot appears smaller than the right foot, but this may result from artistic perspective. The shaman’s left foot is folded underneath his body, and his left knee appears smaller than the patient’s right knee.

The venue for this examination appears to be the inside of a yurt. The shape of the upper portion of the gold vessel is similar to the shape of a yurt. In the background is a wall hanging consisting of small Figure 1s with similarities to the decorations on the clothing of the patient. The clothing material appears to be of woven textiles. Both persons present with luxuriant hair and beards, a common feature in Caucasian males at the time.

Applying current criteria for the classification of inflammatory arthopathy would of course require several longitudinal observations which for obvious reasons are not available. However, other features may suffice. There are several areas of symmetrical swollen joints. Both elbows, including metacarpal areas, wrists and knees appear to be involved. On the right leg the ankle, mid-foot and metatarsals appear swollen. The patient’s right shoe or mukluk has been cut away perhaps to relieve metatarsal swelling.

We suggest that this artistic portrayal shows a patient whose clinical presentation is compatible with moderate to severe inflammatory arthropathy quite possibly RA. However, several other rheumatic diseases, should also be considered in this regard. Although gouty or reactive arthritis could not be unequivocally ruled out, the joint abnormalities of these conditions often present as an asymmetrical oligoarthropathy [13,14]. Whilst Reiter’s syndrome can present symmetrically, it is far less common than RA. In addition, the arthopathy of Reiter’s syndrome tends to involve primarily the small joints more than they do both large and small joints [15].

There were no written descriptions of this historical episode. However, the quality of the pictorial presentation appears to be consistent with inflammatory arthropathy quite possibly RA which has plagued mankind even in ancient Scythia. This historic consultation in a Scythian yurt between shaman and patient could therefore truly represent a “golden” moment in the long history of Rheumatology.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to Dr. Vladmir Matveyev, Deputy Director of the Hermitage Museum for permitting CWD to use photographs of copyrighted material in the preparation of this manuscript. We also wish to acknowledge the cooperation of Valentina A. Nassonova, M.D. Dr. Nassonova (now deceased) was the Director of the Institute of Rheumatology of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences in Moscow when CWD examined the Scythian gold artifacts. She is acknowledged to have worked with CWD and agreed with CWD that the pictorial on the vessel suggested that the person on the left suffered from an inflammatory arthopathy.

8458

References

- Rothschild BM, Woods RJ, Rothschild C, Sebes JI (1992) Geographic distribution of rheumatoid arthritis in ancient North America: implications for pathogenesis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 22: 181-187.

- Aceves-Avila FJ, Medina F, Fraga A (2001) The antiquity of rheumatoid arthritis: a reappraisal. J Rheumatol 28: 751-757.

- Benedek TC (1993) History of rheumatic diseases. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases. (10th Edn), Atlanta.

- Keat A (1983) Reiter's syndrome and reactive arthritis in perspective. N Engl J Med 309: 1606-1615.

- Clary JN. Rheumatoid arthritis. Modern therapeutic options for primary care physicians.

- Dequeker J (1977) Arthritis in Flemish paintings (1400-1700). Br Med J 1: 1203-1205.

- Weinberger A(1998) The Arthritis of Vincent van Gogh's Model, Augustine Roulin. J ClinRheumatol 4: 39-41.

- BoonenA, van de Rest J, Dequeker J, van der Linden S (1997) How Renoir coped with rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ 315: 1704-1708.

- The Hermitage Catalogue -Selected Treasures from a Great Museum. The State Hermitage Museum, Leningrad, Russia.

- Adams FA (1939) On airs, waters and places. The General Works of Hippocrates. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore.

- Edwards NL (2001) Clinical and laboratory features. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases. (12thedn), Atlanta.

- Boumpas D, Illei GR, Tassiulas IO (2001) Psoriatic arthritis. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases, (12thedn), Atlanta.

- Arnett FC (2001) Seronegativespondyloarthropathies. B. Reactive arthritis and enteropathic arthritis. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases. (12th Edn), Atlanta.