Keywords

antibiotics, antibiotic resistance, drug production batches, country of drug manufacture, drug integrity.

Introduction

Nigeria is one of the developing countries that are still currently battling with fake, adulterated and substandard medications [1,2]. As far back as 1960s, almost all clinical drugs in Nigeria were imported drugs from pharmaceutical companies like May & Baker, Pfizer, Beecham, Smithkline, etc. By late 1980, few drugs were imported into the country due their cheaper costs but by early 1990, a number of medications, unfortunately most of which were adulterated, sub-standard, fake or poisonous found their ways into the country. There has been growing universal concern regarding counterfeit medications, in particular, counterfeit antimicrobial drugs, which are a threat to public health, with many devastating consequences for patients, including increased mortality and morbidity [3]. Whereas, there had been situations in which sub-standard or adulterated clinical drugs, which would not be distributed for sale or administration in the countries of manufacture, were specifically produced for some developing countries like Nigeria, so that unscrupulous drug merchants can make more profits at the expense of the lives of patients that would be administered with such medications.

The need for antibiotics is usually driven by high incidence of infectious disease [4], while diarrhoea is one of the most-common reasons for which patients seek medical care, and among the major causes of childhood deaths, provided estimates of deaths from diarrhoea have usually been significantly alarming [5-13]. Considering that under-5 mortality rates is of global significance, with Nigeria currently among those rating highest [14,15]; administration of antibiotics on infants and children in most cases of infantile diarrhoea (gastroenteritis), even sometimes, prior to hospital attendance [2,16-18] cannot be underestimated. However, high prevalence of antibiotic resistance is unfortunately a continually increasing and widely reported problem, most especially among children in developing countries [17,19-25], and sometimes with occasional treatment failure. It is generally believed that the relationship between antibiotic use and emergence of resistance as well as spread of resistance is complex but in spite of ignorance-/complacence-based malpractices of antibiotics therapy being characterised as overused, underused, wrong use and indiscriminate use [26]; still, antibiotic misuse in clinical practices alone cannot explain the high frequency of antibiotic resistant bacteria in developing countries [2,27,28].

Infantile and childhood diarrhoea have been with humans as far back as human memory can recount [29,30]. It seemed at a point in time that there was a dramatic fall in the mortality rates from acute childhood gastroenteritis in developed countries; however, it has always been reported that there were still too many children dying each year from diarrhoea [14-16,19,31], which of course confirms treatment failures in infantile diarrhoeal cases. Clinical/ medical screening for likely prescribed antibiotics, both in adult/infantile infectious disease conditions of bacteria origins is antibiotic susceptibility testing using antibiotic discs. However, it has been proven that results of is antibiotic susceptibility testing using antibiotic discs and corresponding antibiotic drugs vary significantly in most cases, therefore, the current preliminary study assayed for the most-commonly administered paediatric antibiotics, comparing Nigeria and Dubai, a commercial country from where most products are presently imported into the country.

The aim of the current preliminary study therefore, was to compare the in vitro bacteriostatic activities and antibiotic resistance profiles of commonly-available oral paediatric antibiotics sold in Nigeria and Dubai, using diarrhoeagenic bacteria as indicator organisms. This study is a means of determining the potency of oral paediatric antibiotics sold in Nigeria, in comparison with oral paediatric antibiotics sold in another popular commercial country, with largest number of imported products into Nigeria.

Methods

Diarrhoeagenic bacterial species

Test bacteria used in this study were diarrhoeagenic bacterial strains originally isolated from faecal specimens of infants and children between 9 months and 1½ years of age that were presented for weaning diarrhoea at Oni Memorial Children Hospital, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria and at various residences [18]. Stock isolates were reactivated in sterile unbuffered peptone water (Lab M, Basingstoke, England) and incubated for 24-48 h at 35ºC, after which they were sub-cultured by streaking on sterile blood and MacConkey agar (MCC, Lab M, England) to assure purity. Pure isolates were then stored on cystein lactose electrolyte deficient agar (CLED, Lab M, England) slants as bench cultures.

Oral paediatric suspensions

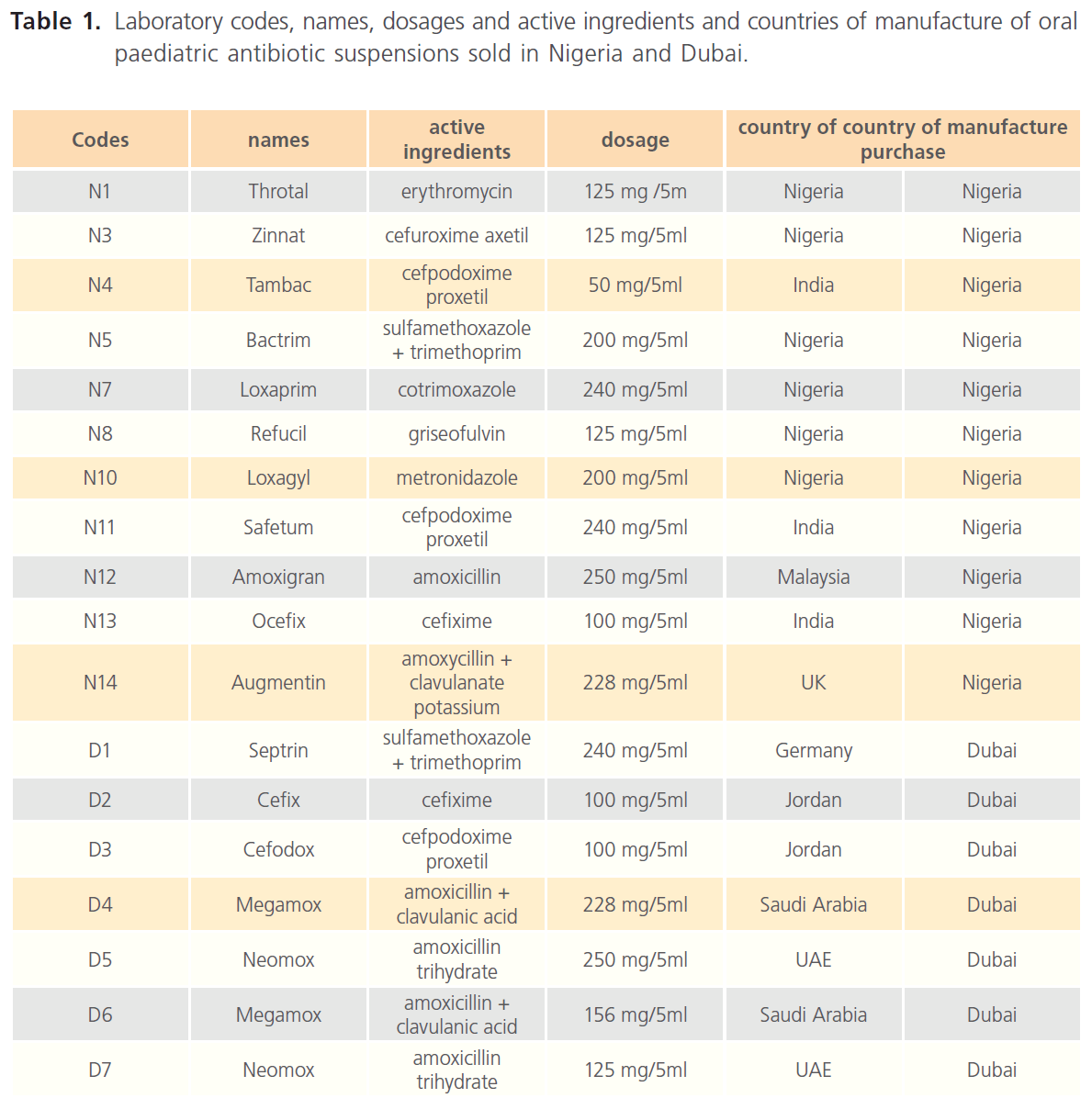

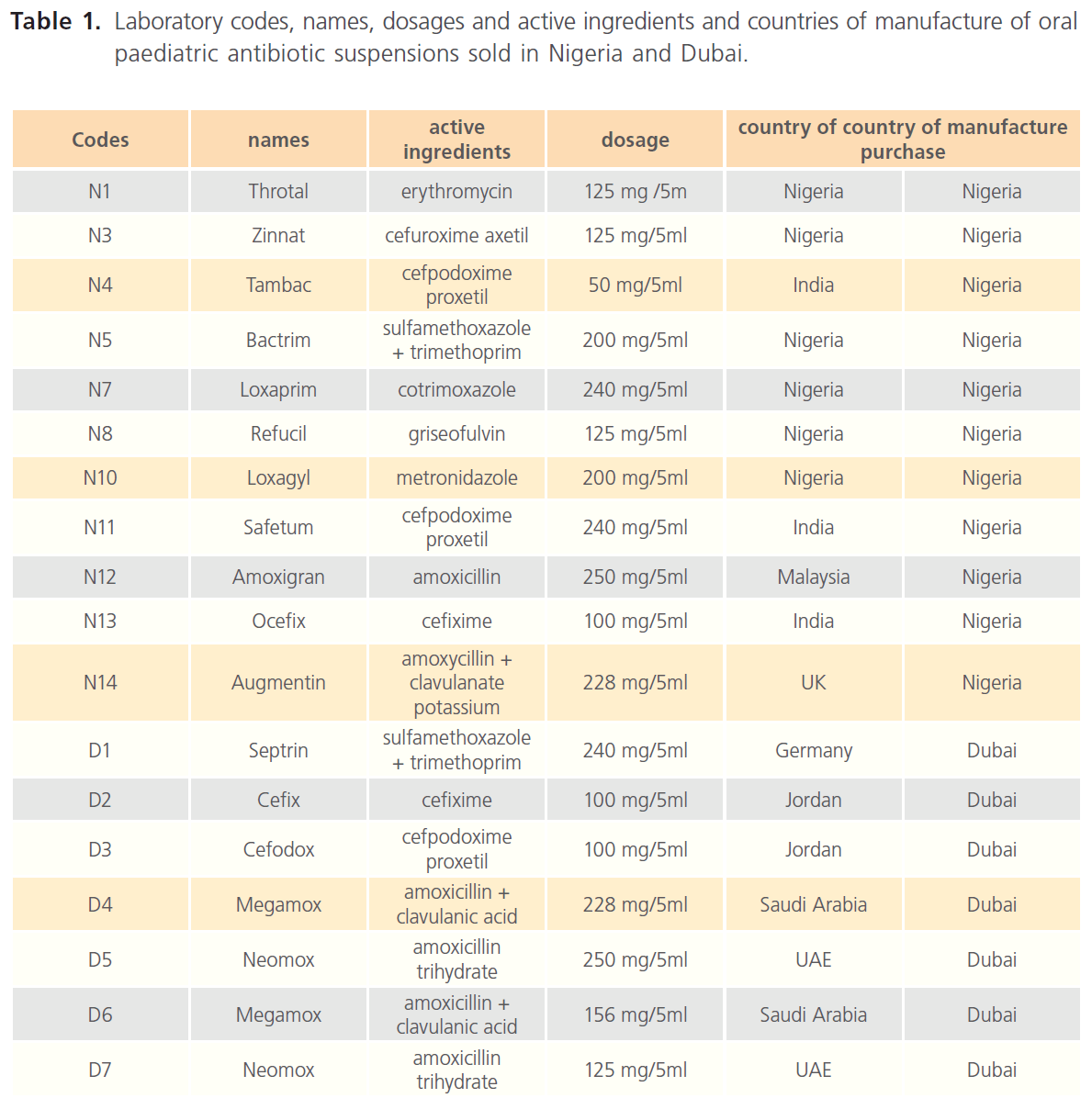

Laboratory codes, names, dosage and active ingredients and countries of manufacture of oral paediatric antibiotics purchased in Nigeria and Dubai are as presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Laboratory codes, names, dosages and active ingredients and countries of manufacture of oral paediatric antibiotic suspensions sold in Nigeria and Dubai.

Antibiotic susceptibility / resistance determination (agar well-diffusion method)

Antibiotic susceptibility/resistance determination was according to the modification of Tagg et al. [32] method, in which about 5 ml of 0.5% sterile plain agar (autoclaved at 1210C for 15 min.) was added to 30 ml of each aqueous suspension of the oral paediatric antibiotics, to avoid spreading of the antibiotic suspensions on the surface of the seeded agar plates. Sterile Mueller-Hinton agar was poured into sterile Petri dishes and allowed to set, after which wells of about 6.0 mm were bored into the agar, followed by surface sterilisation of the agar plates by flaming. Entire surface of each cooled sterile Mueller-Hinton agar plate was then seeded with each diarrhoeagenic bacterial isolate, and the plates were left for about 30 minutes, before aseptically dispensing the oral paediatric antibiotic suspensions into the agar wells. The plates were then incubated at 35ºC for 24-48 hours and zones of inhibition, measured and recorded in millimetre diameter were in triplicates to minimise bias, while zones less than 10.0 mm in diameter or absence of inhibition zones were recorded as resistant (negative).

Results

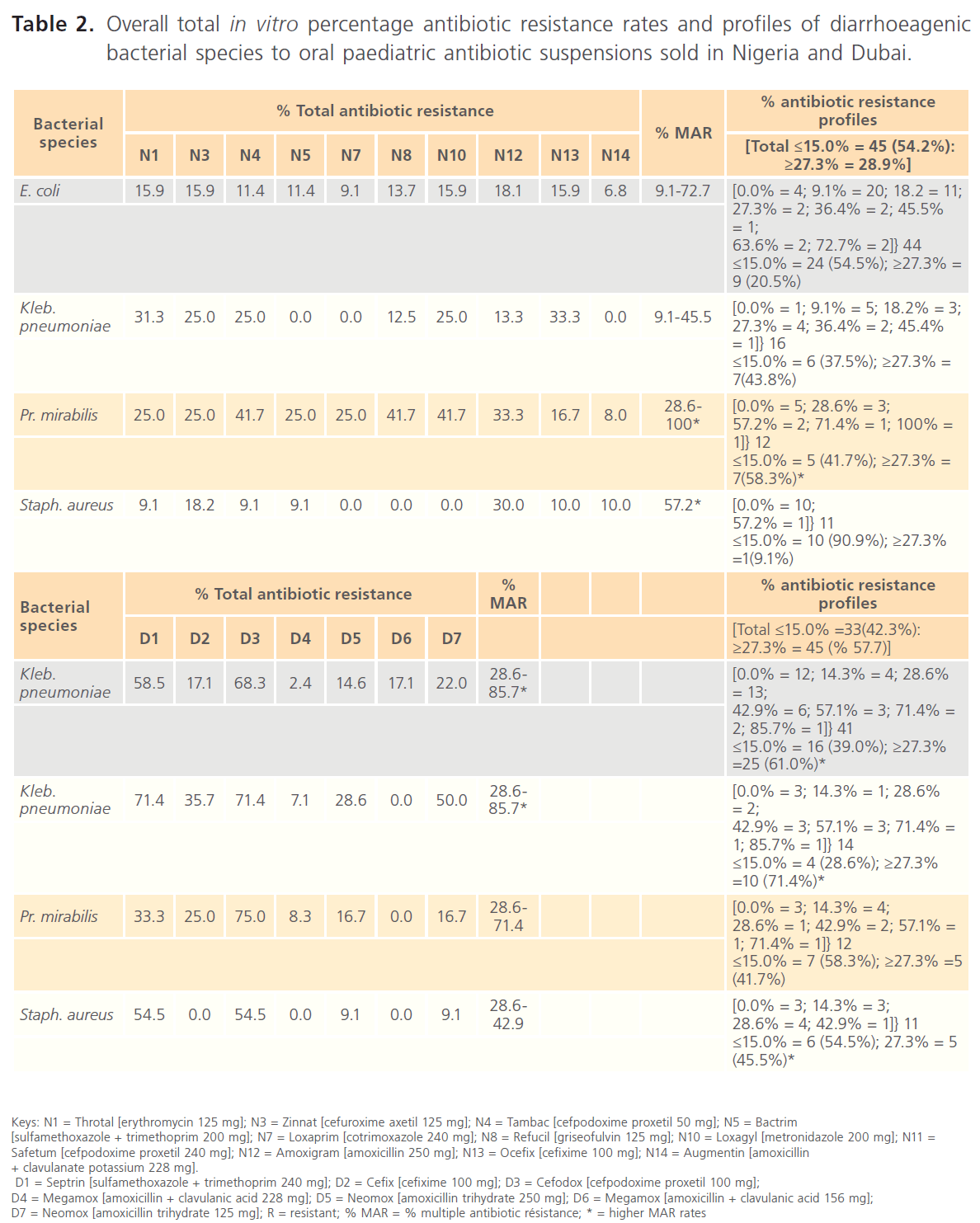

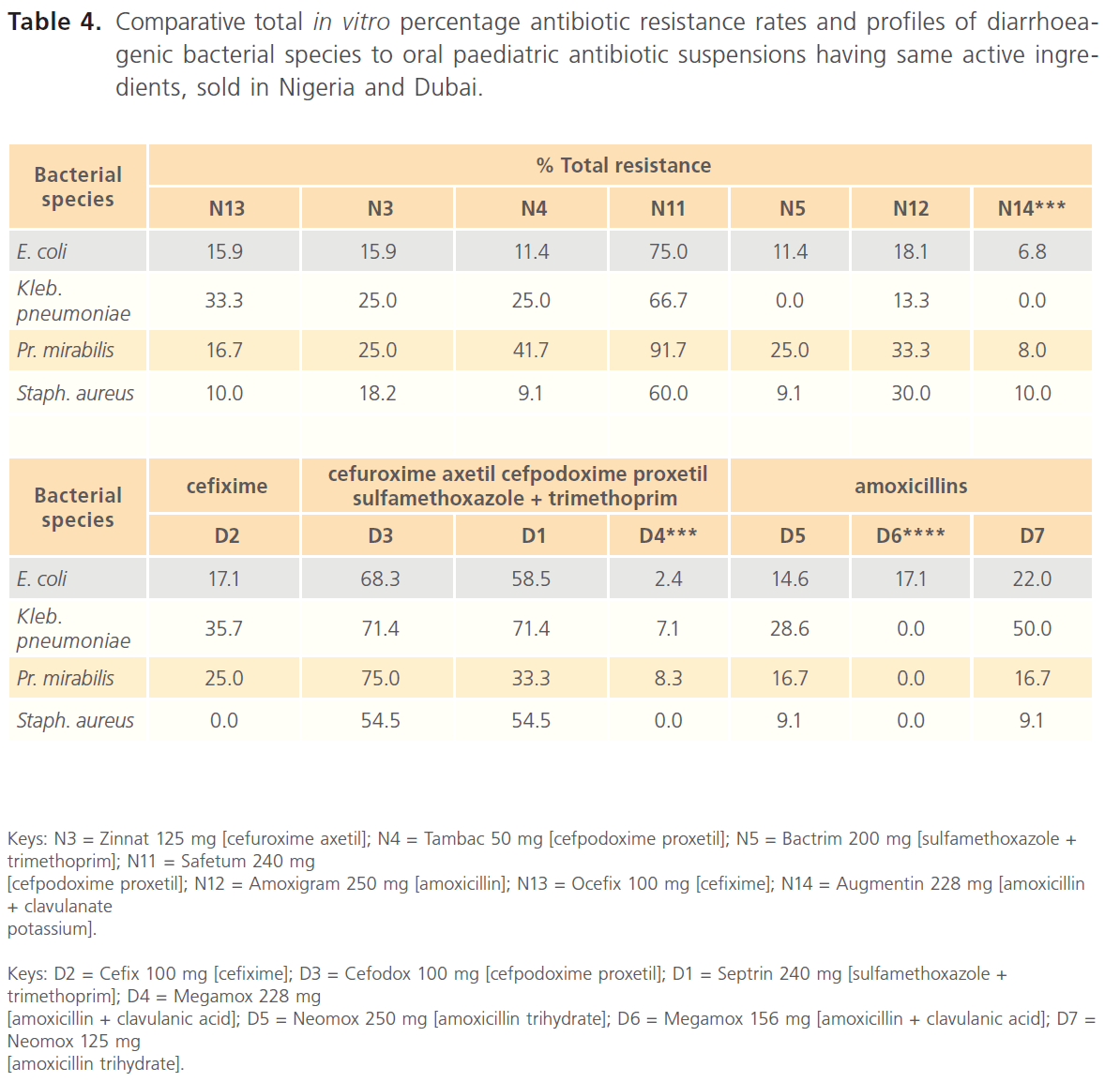

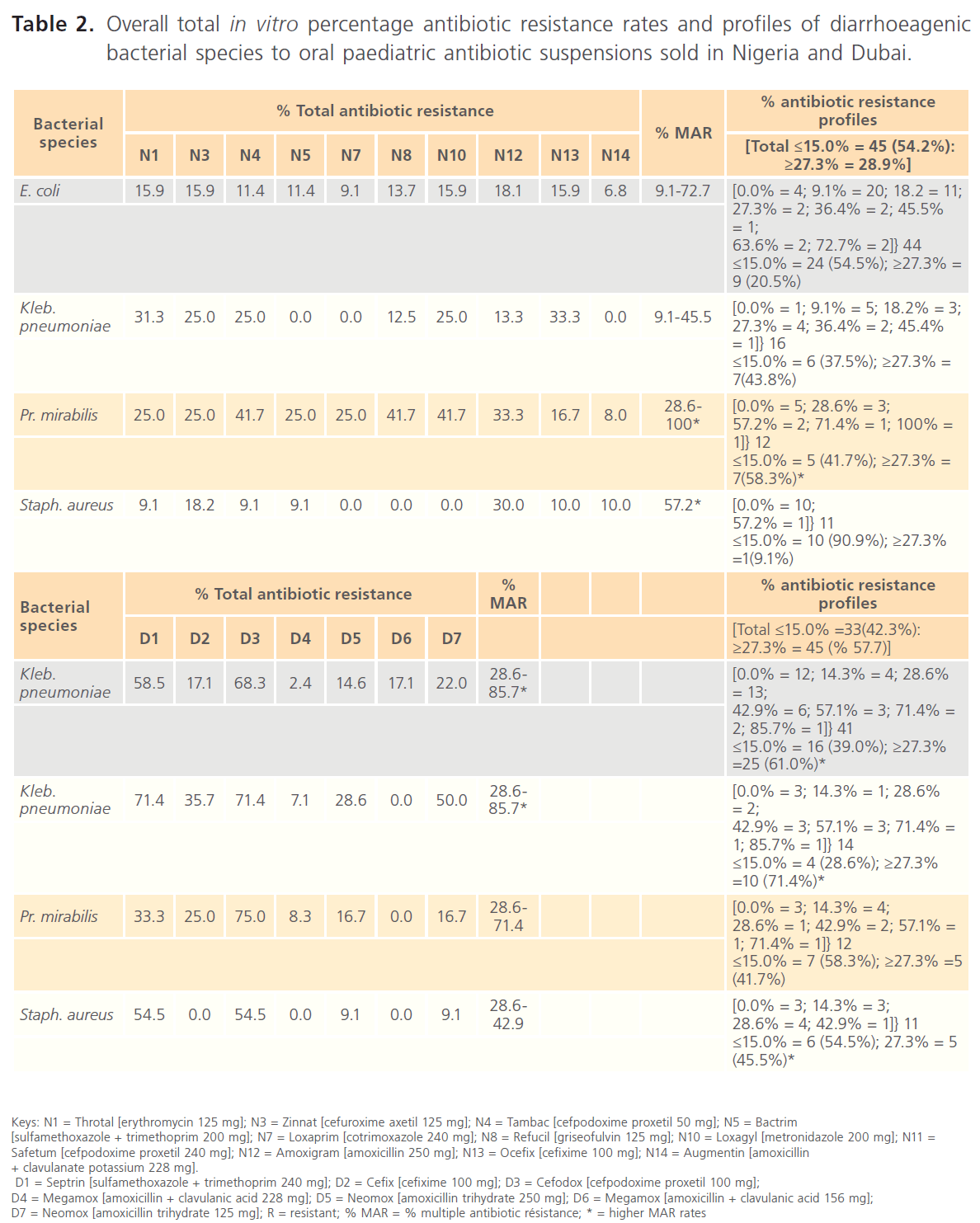

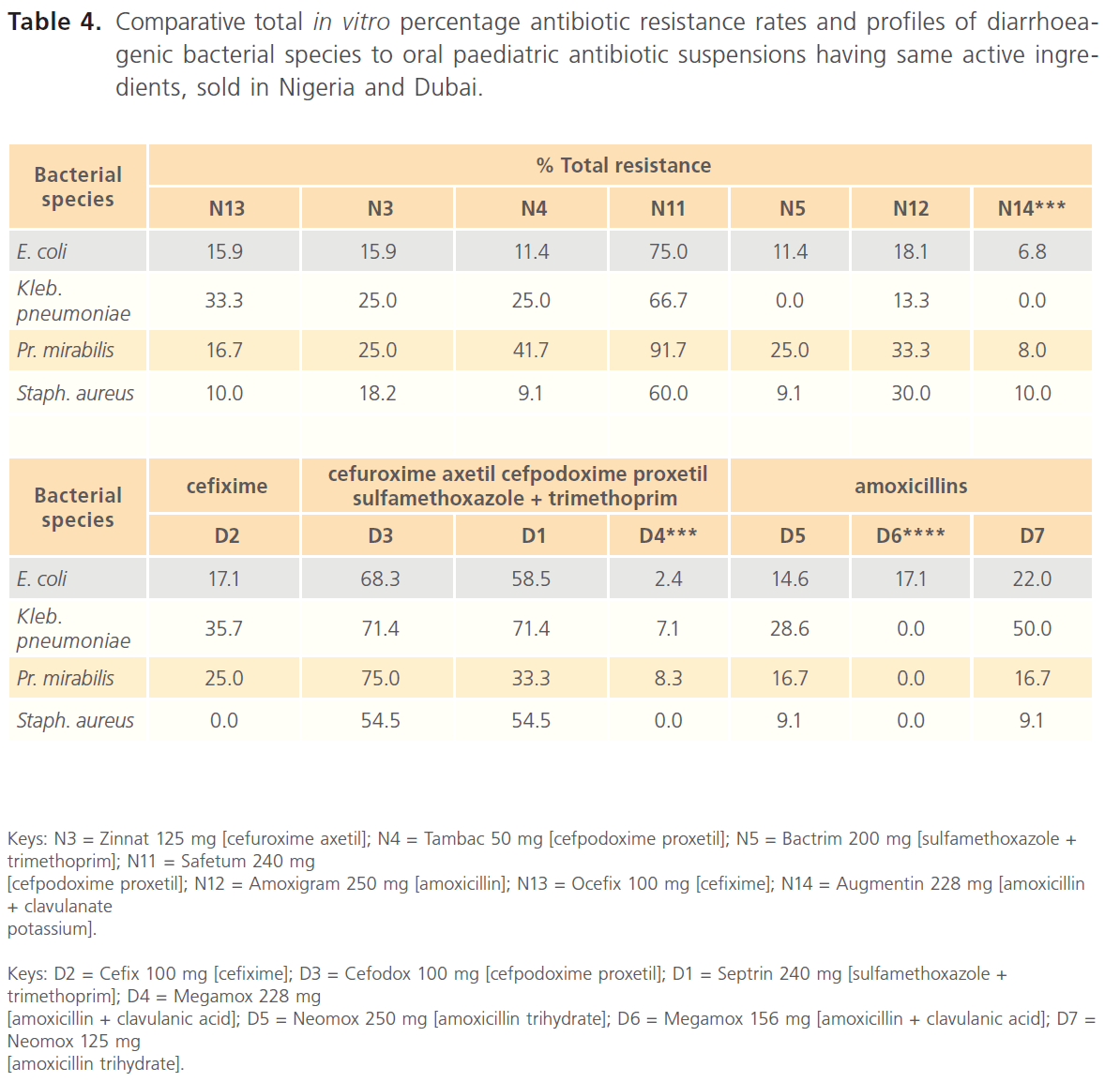

In the current study, 83 diarrhoeagenic bacterial strains of Staphylococcus 11 (13.3%), E. coli 44 (53.0%), Klebsiella pneumoniae 16 (19.3%) and Proteus 12 (14.5%) species exhibited varying in vitro susceptibility/resistance rates, patterns and profiles against the test oral paediatric antibiotics sold in Nigeria and Dubai (Table 1). Overall, Staphylococcus strains were more susceptible to Nigerian-sold paediatric antibiotics, displaying 0.0-30.0% resistance, with the exception of Safetum (N11) [cefpodoxime proxetil 240 mg] to which 60.0% of the Staphylococcus strains exhibited resistance. E. coli strains were more susceptible to Dubai-sold antibiotics, displaying 2.4-22.0% resistance but 58.5% and 68.3% of the E. coli strains were resistant to Septrin (D1) [sulfamethoxazole + trimethoprim 240mg] and Cefodox (D3) [cefpodoxime proxetil 100 mg] respectively (Tables 2 & 4).

Table 2: Overall total in vitro percentage antibiotic resistance rates and profiles of diarrhoeagenic bacterial species to oral paediatric antibiotic suspensions sold in Nigeria and Dubai.

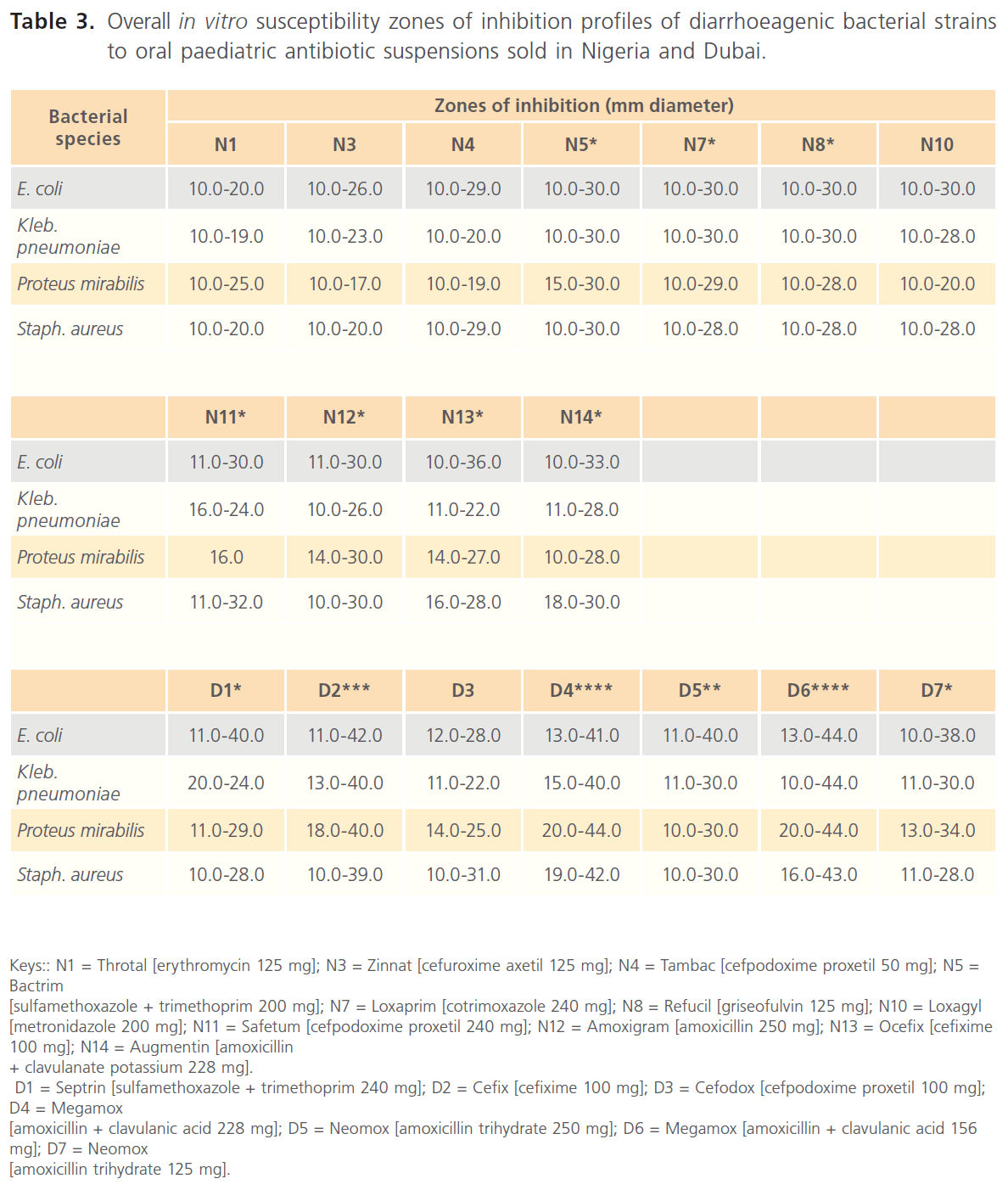

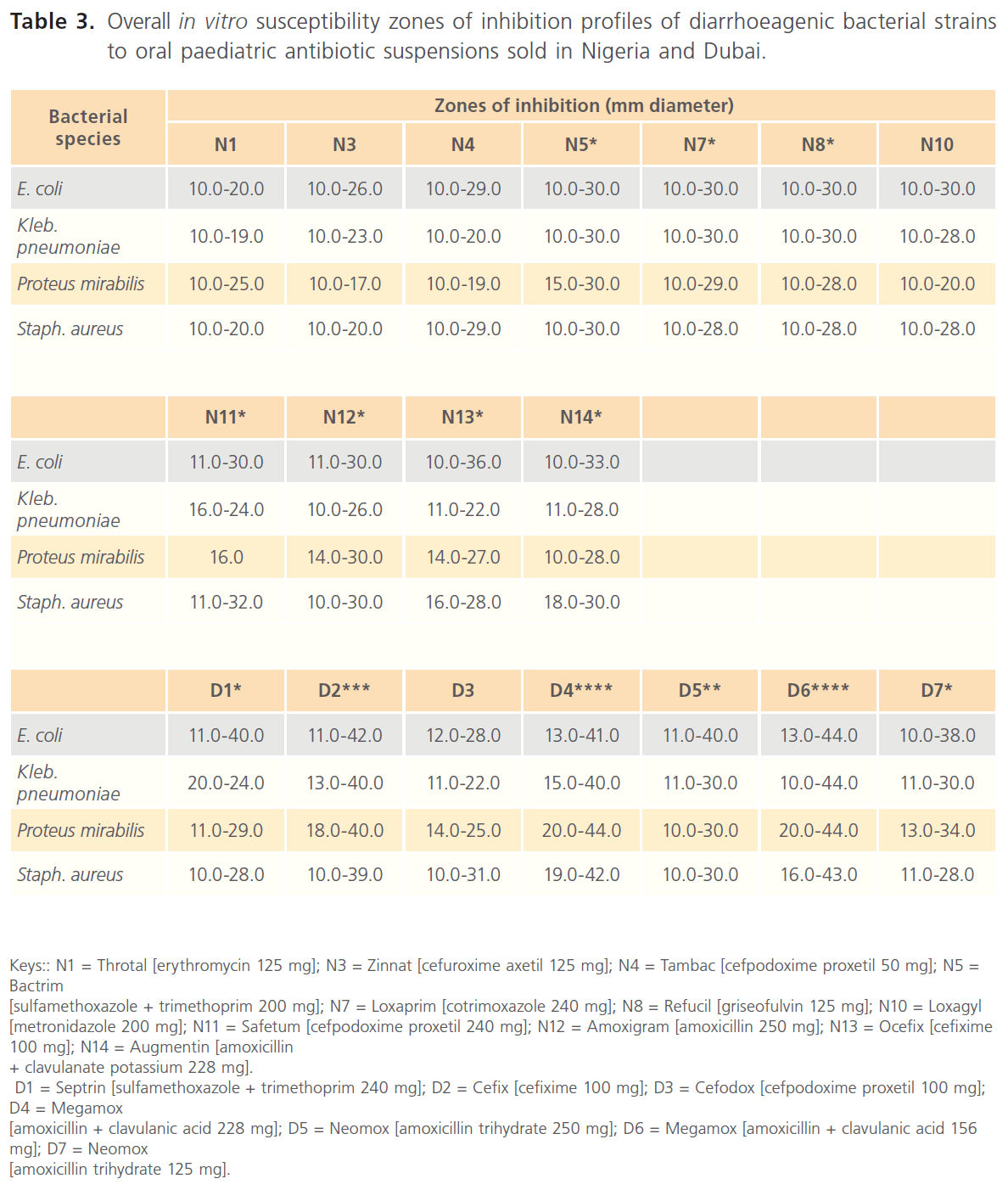

Table 3: Overall in vitro susceptibility zones of inhibition profiles of diarrhoeagenic bacterial strains to oral paediatric antibiotic suspensions sold in Nigeria and Dubai.

Table 4: Comparative total in vitro percentage antibiotic resistance rates and profiles of diarrhoeagenic bacterial species to oral paediatric antibiotic suspensions having same active ingredients, sold in Nigeria and Dubai.

Among the 11 Nigerian-sold paediatric antibiotic suspensions assayed for in this study, the most-resisted was Safetum [cefpodoxime proxetil (240mg) N11], manufactured in India, to which 60.0-91.7% of the diarrhoeagenic bacterial strains were resistant. Relatively lower resistance rates of 0.0-41.7% were recorded for other Nigerian-sold antibiotics, including two other Indian-manufactured antibiotics, Tambac [cefpodoxime proxetil (50 mg/ 5ml) N4] (9.1-41.7%) and Ocefix [cefixime (100 mg/5ml) N13] (10.0-33.3%). The least resisted antibiotic was Augmentin [amoxicillin + clavulanate potassium (228mg) N14], manufactured in UK (Table 2).

Septrin [sulfamethoxazole + trimethoprim (240 mg) D1] manufactured in Germany and Cefodox [cefpodoxime proxetil (100mg) D3] manufactured in Jordan were the most-resisted oral paediatric antibiotics sold in Dubai, with respective resistance rates of 33.3-71.4% and 54.5-75.0%. Lower resistance rates (9.1-50.0%) were exhibited against other antibiotics sold in Dubai, although, Saudi Arabia manufactured Megamox [amoxicillin + clavulanic acid (228mg) D4] and Megamox [amoxicillin + clavulanic acid (156mg) D6], which had resistance rates of 0.0-8.3% and 0.0-17.1% respectively were the least resisted Dubai- sold antibiotics (Table 2).

As shown in Table 2, taking ≤15.0% and ≥27.3% resistance rates as the comparative baselines, the antibiotic resistance profiles of the diarrhoeagenic bacteria to the test oral paediatric antibiotic suspensions indicated that more of the bacterial strains exhibited overall higher resistance rates against paediatric antibiotics sold in Nigeria (≤15.0% = 45 (54.2%): ≥27.3% = 28.9%) than the paediatric antibiotics sold in Dubai (≤15.0% =33(42.3%): ≥27.3% = 45 (% 57.7%). However, Proteus mirabilis strains exhibited less overall resistance against antibiotics sold in Nigeria.

Comparative in vitro susceptibility zones of inhibition profiles of the diarrhoeagenic bacteria to the test oral paediatric antibiotic suspensions indicated general wider zones of inhibitions among the oral paediatric antibiotics sold in Dubai (10.0-44.0 mm in diameter), most especially among the amoxicillins (Tables 2 & 4), while zones of inhibition among the Nigerian-sold antibiotics were 10.0-36.0 mm in diameter. Susceptibility zones of inhibition profiles also indicated that overall inhibitory potentials of paediatric antibiotics sold in Nigeria, in decreasing order were - Bactrim (sulfamethoxazole + trimethoprim 200 mg) [N5]. Augmentin (amoxicillin + clavulanate potassium 228 mg) [N14]. Loxaprim (cotrimoxazole 240 mg) [N7]. Refucil (griseofulvin 125 mg) [N8]. Ocefix (cefixime 100 mg) [N13]. Amoxigram (amoxicillin 250 mg) [N12]. Loxagyl (metronidazole 200 mg) [N10]. Safetum (cefpodoxime proxetil 240 mg) [N11]. Tambac (cefpodoxime proxetil 50 mg) [N4]. Zinnat (cefuroxime axetil 125 mg) [N3]. Throtal (erythromycin 125 mg) [N1] (Tables 1 & 3). Inhibitory potentials of paediatric antibiotics sold in Dubai in decreasing order were Megamox (amoxicillin + clavulanic acid 156 mg) [D6]. Megamox (amoxicillin + clavulanic acid 228 mg) [D4]. Cefix (cefixime 100 mg) [D2]. Neomox (amoxicillin trihydrate 250 mg) [D5]. Neomox (amoxicillin trihydrate 125 mg) [D7]. Septrin (sulfamethoxazole + trimethoprim 240 mg) [D1]. Cefodox ([cefpodoxime proxetil 100 mg) [D3] (Tables 2 & 4).

Nigerian-sold Tambac 50 mg [N4] and Safetum 240 mg [N11], though both manufactured in India and of the same active ingredients (cefpodoxime proxetil), still exhibited significantly different resistance profiles of 9.1-41.7% and 60.0-91.7% respectively (Tables 1 & 3). Similarly, the two amoxicillin derivatives sold in Nigeria, Amoxigram (amoxicillin) 250 mg [N12], manufactured in Malaysia and Augmentin (amoxicillin + clavulanate) 228 mg [N14], manufactured in UK also exhibited relatively significantly different resistance profiles of 13.3-33.3% and 0.0- 10.0% respectively (Tables 1 & 3). Same trend was also recorded among the amoxicillins (amoxicillin + clavulanic acid) sold in Dubai, such that Megamox 228 mg [D4] and 156 mg [D6], manufactured in Saudi Arabia exhibited 0.0-8.3% and 0.0-17.1% respectively, while Neomox 250 mg [D5] and 125 mg [D7], manufactured in United Arab Emirates exhibited 9.1-28.6% and 9.1-50.0% respectively.

Discussion

As far back as 1990s, reports in Nigeria indicated that more than 194,000 children were killed yearly as a result of diarrhoea [14,15,28,33]; while, from time in memorial, after ORS, antibiotics had always been commonly administered in cases of infantile diarrhoea, and sometimes, in cases of dysentery [16,18,21,29,34-36]. Antibiotic administration being either alone or in combination with ORS has been to reduce the bacteriological and clinical symptoms of diarrhoeal conditions. However, authenticity of the alarming increase in antibiotic resistance as a cause of treatment failure in paediatric diarrhoeal infectious conditions has never seriously addressed the likely influence of production batches, country of manufacture or country of purchase of paediatric antibiotics on increasing, globally-reported antibiotic resistance rates.

The clinical/medical screening for likely prescribed antibiotics, both in adult/infantile infectious disease conditions of bacteria origins is antibiotic susceptibility testing using antibiotic discs. However, it has been proven that results of is antibiotic susceptibility testing using antibiotic discs and corresponding antibiotic drugs vary significantly in most cases, therefore, the current preliminary study assayed for the most-commonly administered paediatric antibiotics, comparing Nigeria and Dubai, a commercial country from where most products are presently imported into the country.

Considering the varying antibiotic susceptibility and resistance rates and patterns recorded in the current study, in which there were alternating higher resistance rates among the oral paediatric antibiotics sold in Nigeria and Dubai, it may not be quite easy to confirm that the paediatric antibiotics sold in Nigeria or Dubai were more resistant but taking cognisance of the percentage antibiotic resistance profiles, as well as the zones of inhibition profiles, more of the diarrhoeagenic bacterial strains were susceptible to the Dubai-sold paediatric antibiotics compared to the Nigerian-sold antibiotics but higher percentage antibiotic resistance were more among the Dubaisold paediatric antibiotics, although there were few exceptions. However, result findings of this study confirmed that comparative in vitro susceptibility zones of inhibition profiles indicated wider zones of inhibitions among the oral paediatric antibiotics sold in Dubai.

Bacteriological failure in diarrhoeal cases can be defined as failure to clear diarrhoeagenic pathogen(s) isolated from a patient by the end of treatment period, while bacteriological relapse in diarrhoeal cases can be defined as the re-appearance of a diarrhoeagenic pathogen(s) in stool after the pathogen(s) has been cleared by treatment. Inability of an antibiotic to clear diarrhoeagenic pathogen(s) after therapy can therefore, be regarded as antibiotic resistance. The diarrhoeagenic bacterial strains exhibited significantly different susceptibility and resistance profiles against most of the paediatric antibiotics containing same active ingredients but manufactured by different drug manufacturers. Clinical interpretation and implications of the key findings in the current study are that the recorded differences in vitro percentage antibiotic resistance and percentage multiple antibiotic susceptibility and resistance profiles of the diarrhoeagenic bacterial pathogens towards same antibiotics of same active ingredients but of different brands will mislead in antibiotic prescriptions and can ultimately produce different effects in the patients.

Based on the concepts of antibiotic susceptibility and resistance, it would have been expected that antibiotics of same class and active ingredients should have same antibiotic activities against same bacterial strains, irrespective of country of manufacture or country of sale. It can therefore, be inferred that brands/manufacturers of the paediatric antibiotics are determining factors for the reported antibiotic patterns and profiles in this study and likely in similar cases. A newly introduced concept that can be deduced from findings of this study is that sometimes, reportedly alarming increase in antibiotic resistance may be apparent, since the potencies of some administered antibiotics are inconsistent and thus, questionable in the first place, considering the significant differences in antibiotic susceptibility/resistance profiles of antibiotics presumably containing same active ingredients or of the same class, exhibited against same bacterial strains.

According to Ogunshe [17] and O’Ryan et al. [37], when antimicrobial therapy is appropriate for diarrhoeal cases, selection of a specific antimicrobial agent should be made based upon susceptibility patterns of the aetiological pathogen(s) or information on local antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. This study could not confirm if the concentrations (mg/ml) of the oral paediatric antibiotics had any effect on the bacteriostatic potentials or resistance rates of the antibiotics, since some antibiotics of same active ingredients but different mg/ml concentrations had varying bacteriostatic/resistance rates, irrespective of higher or lower mg/ml concentration. As examples, Nigerian-sold antibiotics, Augmentin (amoxicillin + clavulanate potassium 228 mg) had higher susceptibility rates than Amoxigram (amoxicillin 250 mg), Tambac (cefpodoxime proxetil 50 mg) had higher susceptibility rates than Zinnat (cefuroxime axetil 125 mg). Similarly, Dubai-sold antibiotics, Megamox (amoxicillin + clavulanic acid 156 mg) had higher susceptibility rates than Megamox (amoxicillin + clavulanic acid 228 mg), while Neomox (amoxicillin trihydrate 250 mg) had higher susceptibility rates than Neomox (amoxicillin trihydrate 125 mg).

Regulatory measures such as drug registration can greatly enhance the quality of drugs on the market if effectively implemented, while strict adherence to regulations guarding drug manufactures is expected in every country of the world. But in situations where drug quality is compromised by manufacturing companies, it is mandatory that drug regulating bodies be interested in drugs/drug formularies from countries that are known to manufacture under compromised integrity, and in giving registration numbers to drugs [38]. While very stiff penalties, sometimes execution await those who tamper with clinical drugs and other medications in some countries, it is a well-known fact that in Nigeria, the maximum penalties in most cases are burning of intercepted drugs with press sensations, while drugs not seized find their ways into the Nigerian pharmacies, killing as many Nigerian children and adults as possible.

Infectious diseases are major causes of death in children in developing countries but the additional problem of the presently unstoppable antibiotic resistance is grossly aiding the increasing rates of children mortalities. Even many infectious diseases which were previously controlled by antibiotics are re-emerging due to antibiotic resistance. It is therefore, very important and necessary to consider all the possible and likely factors that can be responsible for the increasing antibiotic resistance, especially in children. According to Bates et al. [38], laboratory tests alone may not be adequate to confirm if a drug is counterfeit or not, and considering the fact that some paediatric antibiotics in Nigeria or which would be imported into the country or worst still manufactured illegally in the country and which were not among those tested in the current study may present with critical results, it is thus, recommended that paediatric antibiotics available in the country be constantly assayed for their bacteriostatic and bactericidal potentials and results made public. Also, as suggested, investigations must be conducted in collaboration with drug regulatory authorities of the countries of manufacture and the manufacturers of the antibiotics with different (lower) susceptibility potentials to the same products obtainable in the country of manufacture.

In conclusion, differences between bacteriostatic potentials of some oral paediatric antibiotics sold in Nigeria and Dubai were indicated, and there is the possibility that worse trends abound in madefor- Nigeria paediatric antibiotics that are imported into Nigeria but which are not currently investigated. Although Africa was found to have the greatest problem with substandard products [38], this is the first study to provide preliminary comparative results on in vitro bacteriostatic potentials of oral paediatric antibiotics obtained from Nigeria and another free-zone commercial country, using infantile diarrhoeagenic bacterial species as indicator bacteria. Some of the diarrhoeagenic bacterial strains that were susceptible to certain antibiotics sold in Nigeria were resistant to corresponding antibiotics sold in Dubai and vice versa. It is therefore; very necessary to regularly consider the inhibitory potentials, as well as resistance profiles of paediatric antibiotics with regards to countries of manufacture and countries of sale, as well as the nature of indigenous bacterial pathogens under investigation.

57

References

- Okeke, IN., Lamikanra, A., Edelman, R. Socioeconomic and behavioral factors leading to acquired bacterial resistance to antibiotics in developing countries. Emer Infect Dis. 1999; 5 (1): 18-27.

- Ogunshe, AAO., Adinmonyema, PO. Evaluation of bacteriostatic potency of expired oral paediatric antibiotic suspensions and implications on infant health. Pan Afr Med J. 2013; in press.

- Kelesidis, T., Kelesidis, I., Rafailidis, PI., Falagas, ME. Counterfeit or substandard antimicrobial drugs: A review of the scientific evidence. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007; 60 (2): 214-236.

- Kunin, CM. Resistance to antimicrobial drugs. A worldwide calamity. Ann Intern Med. 1993; 118: 557-561.

- Torres, ME., Pirez, MC., Schelotto, F., Varlea, G., Parodi, V., Allende, F. et al. Etiology of children’s diarrhea in Montevideo, Uruguay: Associated pathogens and unusual isolates. J Clin Microbiol . 2001; 39: 2134-2139.

- Williams, BG., Gouws, E., Boschi-Pinto, C., Bryce, J., Dye, C. Estimates of world-wide distribution of child deaths from acute respiratory infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002; 2: 25-32.

- Kosek, M., Bern, C., Guerrant, R. The global burden of diarrhoeal disease as estimated from studies published between 1992 and 2000. Bull World Health Organ. 2003; 81: 197-204.

- Morris, SS., Black, RE., Tomaskovic, L. Predicting the distribution of under-five deaths by cause in countries without adequate vital registration systems. Int J Epidemiol. 2003; 32: 1041-1051.

- Parashar, UD., Hummelman, EG., Bresee, JS., Miller, MA., Glass, RI. Global illness and deaths caused by rotavirus disease in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003; 9: 565-572.

- Thapar, N., Sanderson, IR. Diarrhoea in children: An interface between developing and developed countries. Lanc 2004; 363: 641-653.

- Bryce, J., Boschi-Pinto, C., Shibuya, K., Black, RE. WHO estimates of the causes of death in children. WHO Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group. Lanc 2005; 365 (9465): 1147-1152.

- Lawn, JE., Cousens, S., Zupan, J. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? Lanc 2005; 365: 891-900.

- Rowe, AK., Rowe, SY., Snow, RW., Korenromp, EL., Armstrong Schellenberg, JRM., Stein, C. et al. The burden of malaria mortality among African children in the year 2000. Int J Epidemiol. 2006; 35: 691-704.

- UNICEF. UNICEF Report, September 2011. Online: https://www. childinfo.org/mortality_ufmrcountrydata.php) [Accessed 21 November 2012].

- UNICEF. Diarrhoea kills 194000 children yearly in Nigeria. Online: https://dailypost.com.ng/2012/11/21/diarrhoea-kills-194000-children-yearly-nigeria-unicef/. [Accessed 21 November 2012].

- Walker-Smith, JA. Management of infantile gastroenteritis. Arch Dis Child. 1990; 65 (9): 917-918.

- Ogunshe, AAO. Effect of production batches of antibiotics on in vitro selection criterion for potential probiotic candidates. J Medicinal Foods 2008; 11 (4): 753-760.

- Ogunshe, AAO., Gbadamosi, EM. Paediatric health implication of ogi and omi dun as potential complementary therapy for teething-diarrhoeal control. Rawal Med J. 2011; 36 (1): 45-49.

- Meng, CY., Smith, BL., Bodhidatta, L., Richard, SA., Vansith, K., Thy, B. et al. Etiology of diarrhea in young children and patterns of antibiotic resistance in Cambodia. Ped Infect Dis. 2011; 30 (4): 331-335.

- Brueggemann, AB. Antibiotic resistance mechanisms among pediatric respiratory and enteric pathogens: A current update. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006; 25 (10): 969-973.

- Nguyen, TV., Le Van, P., Le Huy, C., Nguyen, GK., Weintraub, A. Etiology and epidemiology of diarrhea in children in Hanoi, Vietnam. Int J Infect Dis. 2006; 10 (4): 298-308.

- Ogbu, O., Agumadu, N., Uneke, CJ., Amadi, ES. Aetiology of acute infantile diarrhoea in the South-Eastern Nigeria: An assessment of microbiological and antibiotic sensitivity profile. The Internet J Third W Med. 2008; 7 (1).

- Ogunshe, AAO., Olaomi, JO. In-vitro phenotypic bactericidal effects of indigenous probiotics on bacterial pathogens implicated in infantile bacterial gastroenteritis using Tukey-HSD test. Am J Infect Dis. 2008; 4 (2): 162-167.

- Ogunshe, AAO., Oyero, OM., Olabode, OP. Microbial studies on bacterial co-pathogens in paediatric clinical samples positive for polio virus. Asian Pacific J Trop Med. 2009; 2 (1): 1-6.

- Ogunshe, AAO., Fawole, AO., Ajayi, VA. Microbial evaluation of public health implications of urine as alternative therapy in paediatric cases. The Pan Afr Med. 2010; 5 (12).

- Alvan, G., Edlund, C., Heddini, A. The global need for effective antibiotics - a summary of plenary presentations. Drug Resist Updates 2011; 14 (2): 70-76.

- Col, NF., O’Connor, RW. Estimating worldwide current antibiotic usage: report of Task Force 1. Rev Infect Dis. 1987; 9 (Suppl. 3): S232-S243.

- Vazquez-Lago, JM., Lopez-Vazquez, P., López-Durán, A., Taracido-Trunk, M., Figueiras, A. Attitudes of primary care physicians to the prescribing of antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance: A qualitative study from Spain. Fam Pract. 2012; 29 (3): 352-360.

- Kadison, ER., Borovsky, MP. The treatment of infantile diarrhea with a new combination of antibiotics. J Ped. 1951; 38 (5): 576-589.

- Neter, E., Webb, CR., Shumway, CN., Murdock, MR. Study on etiology, epidemiology, and antibiotic therapy of infantile diarrhea, with particular reference to certain serotypes of Escherichia coli. Am J Public Health Nations Health 1951; 41 (12): 1490-1496.

- Diskin, A., Ervin, M., Talavera, F., Hardin, E., Halamka, JD., Dronen, SC. Gastroenteritis in emergency medicine; 2011. Online: https:// emedicine.medscape.com/article/775277-overview. [Accessed 08 August 2011].

- Tagg, JR., Dajani, AS., Wannamaker, LW. Bacteriocins of Gram-positive bacteria. Bacteriol Revs. 1976; 40: 722-756.

- Babaniyi, OA. Oral dehydration of children with diarrhea in Nigeria, a 12 year renew of impact on morbidity and mortality from diarrhea disease and diarrhea treatment practices. J Trop Paed. 1991; 37: 16-66.

- Alabi, SA., Audu, RA., Ouedeji, KS. Viral, bacteria and parasitic agents associated with infantile diarrhea in Lagos. Nig J Med Res. 1998; 2: 29-32.

- Cheever, FS. The acute diarrheal diseases of bacterial origin Bull of the New York. Acad Med. 1955; 31 (9): 611-626.

- Traa, BS., Fischer Walker, CL., Muno, M., Black, RE. Antibiotics for the treatment of dysentery in children. Int J Epidemiol. 2010; 39 (Suppl. 1): i70-i74.

- O’Ryan, M., Prado, V., Pickering, LK. A millennium update on pediatric diarrheal illness in the developing world. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2005; 16 (2): 125-136.

- Bate, R., Mooney, L., Milligan, J. The danger of substandard drugs in emerging markets: An assessment of basic product quality. Pharmacolog 2012; 3 (2): 46-51.