Al-Ola Abdallah1, Meghana Bansal1, Steven A Schichman2,3, Zhifu Xiang1,4*

Division of Hematology and Oncology, Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, Arkansas, USA

Department of Pathology, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, Arkansas, USA

Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Service, Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System, Little Rock, Arkansas, USA

Division of Hematology and Oncology, Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System, Little Rock, Arkansas, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Xiang Division of Hematology and Oncology

Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute

University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. Little Rock, Arkansas, USA

Tel: 918-2616196

Fax: 501 257 4942

E.mail: ZXiang@uams.edu

Keywords

Inversion 16 AML, Trisomy 22 AML, Deletion 7 AML, FLT3 (ITD)

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a heterogeneous neoplastic disorder characterized by the accumulation of immature myeloid blasts in the bone marrow with or without the involvement of peripheral blood [1]. The recent World Health Organization (WHO) classification of neoplasms divides AML into distinct disease entities on the basis of underlying morphology, cytogenetics, immunophenotype and clinical data [2]. One of the most recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities in AML is inv (16) (p13q22), which is usually associated with acute myelomonocytic leukemia with eosinophilia (AML M4-Eo by the French–American–British classification) [3]. On cytogenetic analysis, inv (16) is detected in approximately 8% of adults diagnosed with AML [4]. More than 90% of patients with inv (16)/t(16;16) AML harbor secondary chromosome aberrations (e.g., trisomy 22) and/or mutations affecting N-RAS, K-RAS, KIT, and FLT3 [5]. 7q deletions represent a more frequent genetic alteration occurring in approximately 10% of CBF-AML cases [6]. We present a case of de novo AML that involved inv (16) associated with trisomy 22, 7q deletion and FLT3 (ITD) mutation.

Case Report

A 72-year old white female patient presented to the hospital with fatigue, malaise, rhinorrhea, cough, and dyspnea with exertion. She denied having fever, night sweats, weight loss, decreased appetite, or bleeding. Her physical examination was unremarkable. Her Complete Blood Count (CBC) revealed a total White Blood Cell (WBC) count of 19.4 × 103/μL with 10% circulating blasts, 6% neutrophils, 26% lymphocytes, and 56% monocytes. Her hemoglobin was 6.40 g/dL and hematocrit was 18.4%. The platelet count was 10 × 103/μL, and reticulocytes measured 0.0178 × 106 /μL. Creatinine was 2.7 mg/dL, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 490 U/L, and uric acid was 13.7 mg/ dl. The peripheral blood smear showed dysplastic monocytes, immature monocytes, immature granulocytes, and blasts. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy showed 100% cellularity with approximately 40% blasts and immature mononuclear cells with features suggestive of monocytoid differentiation and numerous eosinophils. Flow cytometry analysis of the bone marrow aspirate showed approximately 22% blasts expressing CD45, CD13, CD33, CD117, HLA-DR, CD34 and myeloperoxidase. CD4 and CD7 were faintly expressed, and CD10, TdT, CD19, CD20 were negative in blast population. Based on the clinical presentation and pathologic findings, a diagnosis of acute monoblastic leukemia was made.

Cytogenetic Analysis

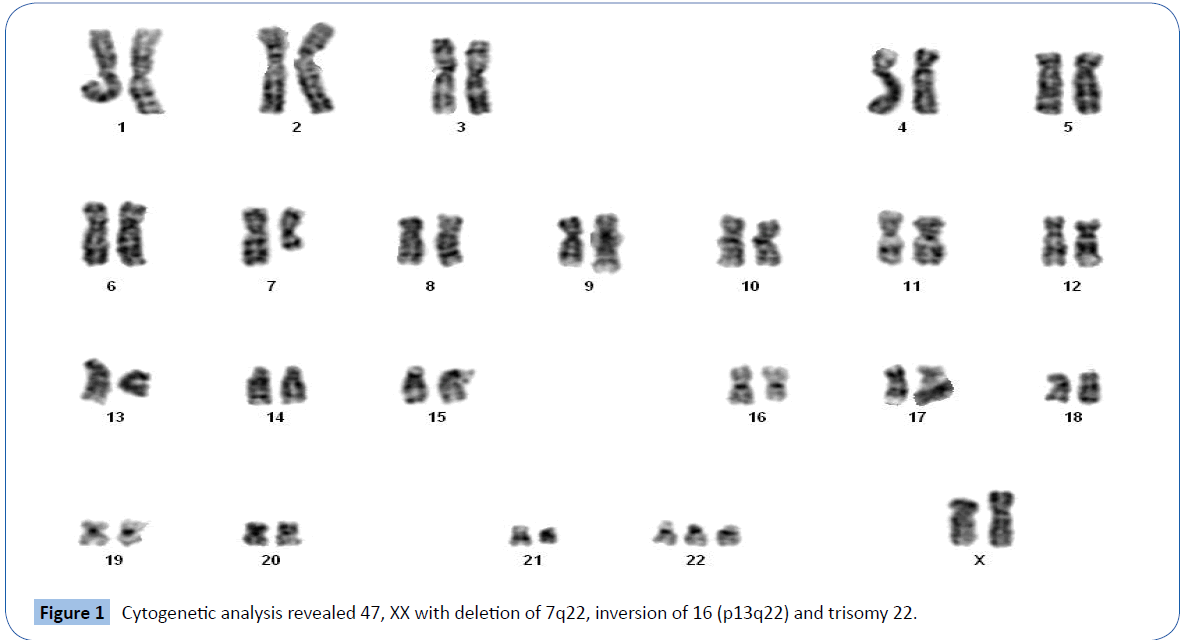

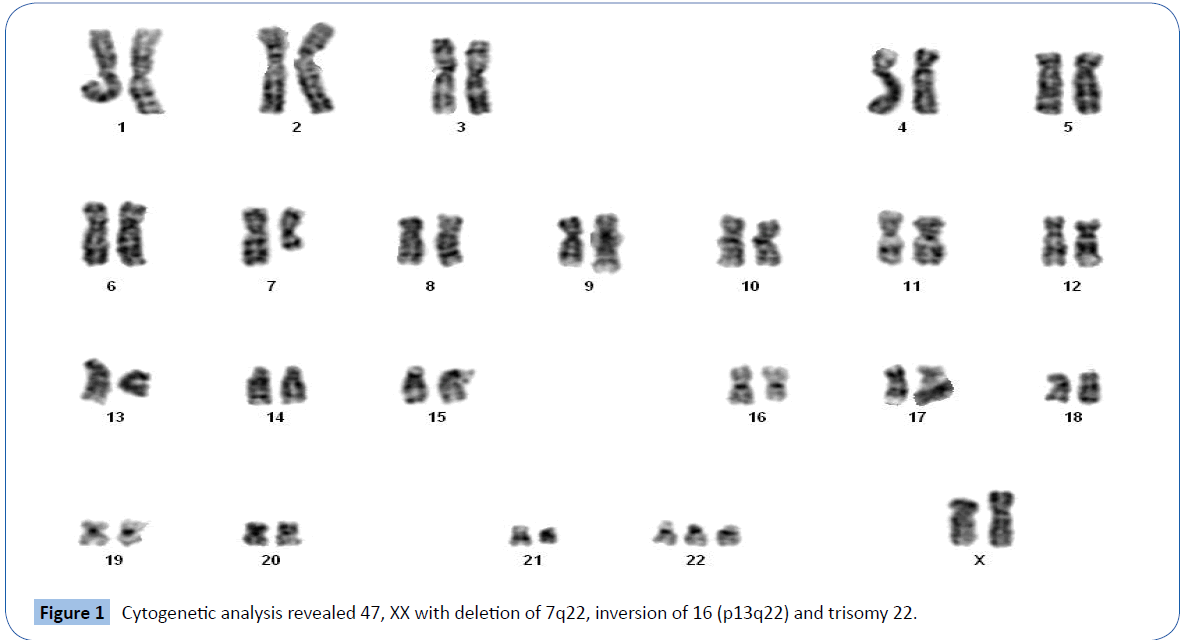

A 24-h culture with 2-h mitotic arrest on unstimulated bone marrow cells was applied, and the chromosomes were analyzed using Trypsin-Giemsa (GTG) banding of 20 metaphases at a ~450 band resolution. The karyotype was defined according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature 2009 guidelines [7].

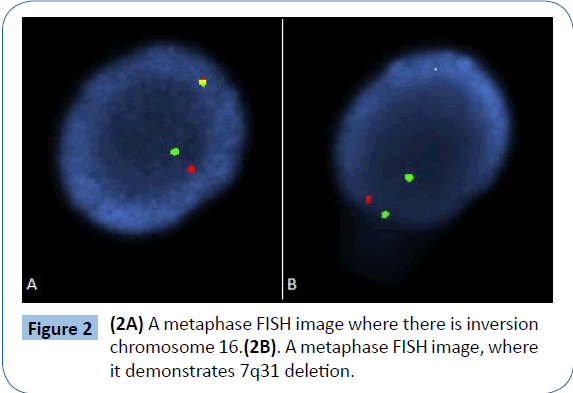

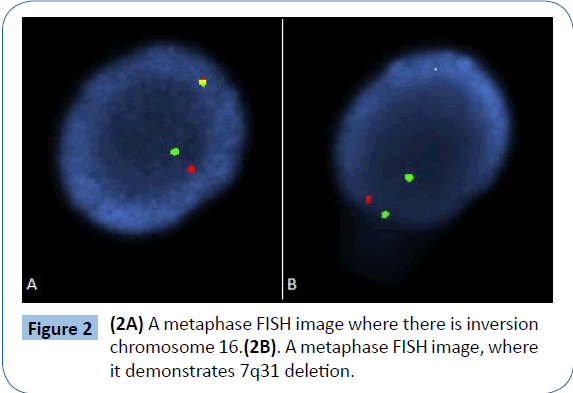

Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization

Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization (FISH) analysis was done using DNA FISH probes (Abbott Molecular, Inc) specific for the pericentromeric region of chromosome 8, putative tumor suppressor gene regions at 5q31, 7q31, 20q12 and RUNX1T1/ RUNX1 [t(8;21)], CBFB (inv 16), KMT2A (11q23) and PML/RARA [t(15;17)] oncogenes. The FISH analysis targeting MYC utilized a dual color probe cocktail with specificity for the 3’ and 5’ ends of the gene.

Mutation analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from patient’s peripheral blood. Mutation analysis by a combination of PCR and direct sequencing was performed by Integrated Oncology Group at LabCorp. Somatic mutations were analyzed in AML-associated genes CEBPA, NPM1, c-KIT, and FLT3 (both ITD and TKD).

Results

Cytogenetic analysis of GTG banded metaphases revealed 47 XX chromosomes with deletion of 7q22, inversion of 16 (p13q22) and trisomy 22 (Figure 1) in all dividing cells. FISH analysis of the patient’s bone marrow revealed 96% CBFB gene rearrangement in nuclei (Figure 2A), and the 7q31 deletion was present in 95% of nuclei analyzed (Figure 2B). The results for probes targeting 5q, RUNX1T1/RUNX1, KMT2A and RARA/PML were normal. There were no AML-associated mutations detected in CEBPA, c-KIT, NPM1 and FLT3 TKD genes, however, FLT3 ITD was detected. The patient was considered to have a high risk for development of AML. However, given her advanced age and other comorbidities, she was not considered a candidate for allogeneic stem cell transplant.

Figure 1: Cytogenetic analysis revealed 47, XX with deletion of 7q22, inversion of 16 (p13q22) and trisomy 22.

Figure 2: (2A) A metaphase FISH image where there is inversion chromosome 16.(2B). A metaphase FISH image, where it demonstrates 7q31 deletion.

A remission induction chemotherapy regimen began with a 7+3 regimen that consisted of cytarabine 100 mg/m2 intravenous infusion daily on days 1 to 7 and idarubicin 12 mg/m2 intravenous infusion daily on days 1 to 3. The patient tolerated the induction therapy well, but she developed some confusion and seizure-like activity that subsided by the end of the cycle. A post-induction bone marrow biopsy on day 14 showed a hypocellular marrow without any evidence of blasts, and a bone marrow biopsy from day 28 showed 65% cellularity with trilineage hematopoiesis without detectable blasts by morphology and flow cytometry.

Because of the patient’s neurological symptoms during the induction treatment and her advanced age, she received three cycles of consolidation with a 5+2 regimen, consisting of cytarabine 100 mg/m2 intravenous infusion daily on days 1 to 5 and idarubicin 12 mg/m2 intravenous infusion daily on days 1 and 2. She tolerated the consolidation therapy well with hematological recovery and has remained in remission to date.

Discussion

AML is more commonly found in older patients [8,9]. SEER data indicate a median age at diagnosis of 66 years [8]. The prognosis with AML worsens as the age of the patient increases [10-12]. Based on the current WHO classification system, more than twothirds [13] of cases of AML can be categorized on the basis of their underlying cytogenetic or molecular genetic abnormalities [14]. In a retrospective study of 35 elderly patients with AML who received intensive chemotherapy, there were 17 cases of remission after induction chemotherapy. Treatment-related mortality occurred at a rate of 22.9%, and the median overall survival (OS) was 7.9 months. Multivariate analysis indicated that significant prognostic factors for OS included performance status, platelet count, blast count, cytogenetic risk category, and intensive chemotherapy. Subgroup analysis showed that intensive chemotherapy was markedly effective in the relatively younger patients (65-70 years) and those with de novo AML, better-to-intermediate cytogenetic risk, and normal albumin levels [15]. In a retrospective study, the role of induction and consolidation therapy in patients over the age of 60 showed median OS 11 months with complete remission rate of 58.3%, and treatment-related death was 15.4%. Successful induction was related to good performance. Mortality correlated with failure to achieve Complete Remission (CR). In CR patients, poor karyotype and absence of consolidation correlated with mortality. More than one cycle of consolidation was associated with better OS. Intensive induction in patients with good performance and less than one cycle of consolidation after CR may be the best strategy for improving OS in elderly AML patients [16].

For patients with de novo AML, the best clinical approach is the classic cytogenetic analysis including FISH to categorize patients into specific risk groups. Inv (16), detected in approximately 8% of adults diagnosed with AML [4], leads to fusion of the core-binding factor subunit (CBFB,PEBP2B) gene on chromosomal band 16q22 with the smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (MYH11) gene on 16p13 [17]. Secondary chromosomal aberrations are present in 35% to 40% of inv (16) AML cases, with trisomy 22 representing the most frequent abnormality [18-20]. Trisomy 22 is a favorable prognostic factor for relapse free survival in AML with inv (16) [5]. Trisomy 22 occurs in 18% of patients with inv (16) AML [5]; 7q deletions occur in 10% [6]; and the FLT3 (ITD) mutation occurs in 5% [5]. A study from MD Anderson Cancer Center showed that FLT3-ITD and FLT3-TKD mutations as a group conferred inferior progression-free survival in inv (16) AML [21]. In general AML patients with the FLT3/ITD mutation have shorter remission duration and shorter OS [22]. However the 7q deletion did not show any effect on the relapse free survival, complete remission or OS [5]. Identification of secondary chromosomal aberrations and gene mutations in inv (16) AML are important to determine favorable and unfavorable prognosis [5].

Our case presents an elderly patient with de novo AML who had inv (16) in association with trisomy 22, del 7q and FLT3 (ITD) mutation. Following intensive chemotherapy the patient achieved complete remission. It is difficult to predict the effect of this complex cytogenetic abnormalities on clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

We present the case of an elderly patient with inv (16) AML in association with trisomy 22, del 7q, and FLT3 (ITD) mutation, which is rare a presentation. Although there were several factors that showed unfavorable prognosis in this case presentation, achieving complete response might reflect that trisomy 22 in association with inv (16) confers a dominant favorable prognosis regardless of other risk factors. Although our patient responded well to therapy and remained in remission at 16 months of follow-up, long-term follow-up is needed to accurately assess the prognostic significance of trisomy 22 in inv (16) AML.

7043

References

- Villela L,Bolanos-Meade J (2011) Acute myeloid leukaemia: optimal management and recent developments. Drugs 71: 1537-1550.

- Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, Brunning RD, Borowitz MJ, et al. (2009) The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood 114: 937-951.

- Voute PA, Barrett A, Stevens MCG, Caron H.N (2005) Cancer in children: clinical management (5th edn) Oxford University Press, New York.

- Byrd JC, Mrozek K, Dodge RK (2002) Pretreatment cytogenetic abnormalities are predictive of induction success, cumulative incidence of relapse, and overall survival in adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8461). Blood 100: 4325-4336.

- Paschka P, Du J, Schlenk RF, Gaidzik VI, Bullinger L, et al. (2013) Secondary genetic lesions in acute myeloid leukemia with inv(16) or t(16;16): a study of the German-Austrian AML Study Group (AMLSG). Blood 121: 170-177.

- Kühn MW, Radtke I, Bullinger L, Goorha S, Cheng J, et al. (2012) High-resolution genomic profiling of adult and pediatric core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemia reveals new recurrent genomic alterations. Blood 119: e67-75.

- Shaffer LG, Slovak ML, Campbell LJ (2009) ISCN 2009: An international system for human cytogenetic nomenclature.

- National Cancer Institute. SEER stat fact sheets: acute myeloid leukemia. 2012.

- Fey MF, Dreyling M (2010) Acutemyeloblasticleukaemias and myelodysplastic syndromes in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol21: v158–v161.

- Döhner H, Estey EH, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Büchner T, et al. (2010) Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood 115: 453-474.

- Pollyea DA, Kohrt HE, Medeiros BC (2011) Acute myeloid leukaemia in the elderly: a review. Br J Haematol 152: 524-542.

- O'Donnell MR, Abboud CN, Altman J, Appelbaum FR, Arber DA, et al. (2012) Acute myeloid leukemia. J NatlComprCancNetw 10: 984-1021.

- Schlenk RF, Ganser A, Dohner K (2010) Prognostic and predictive effect of molecular and cytogenetic aberrations in acute myeloid leukemia. ASCO Educational Book.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E,Harris NL (2008) WHO Classification of Tumours of the Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. (4th edn) Geneva, WHO Press, Switzerland.

- Kim DS, Kang KW, Yu ES (2015) Selection of Elderly Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients for Intensive Chemotherapy: Effectiveness of Intensive Chemotherapy and Subgroup Analysis. ActaHaematol133:300-309.

- Kim SJ, Cheong JW, Kim DY, Lee JH, Lee KH, et al. (2014) Role of induction and consolidation chemotherapy in elderly acute myeloid leukemia patients. Int J Hematol 100: 141-151.

- Liu P, Tarle SA, Hajra A (1993) Fusion between transcription factor CBF beta/PEBP2 beta and a myosin heavy chain in acute myeloid leukemia.Science. 261:1041-1044.

- Schlenk RF, Benner A, Krauter J (2004) Individual patient data-based meta-analysis of patients aged 16 to 60 years with core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia: a survey of the German Acute Myeloid Leukemia Intergroup. J ClinOncol 22:3741-3750.

- Marcucci G, Mrózek K, Ruppert AS, Maharry K, Kolitz JE, et al. (2005) Prognostic factors and outcome of core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia patients with t(8;21) differ from those of patients with inv(16): a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J ClinOncol 23: 5705-5717.

- Grimwade D, Hills RK, Moorman AV (2010) Refinement of cytogenetic classification in acute myeloid leukemia: determination of prognostic significance of rare recurring chromosomal abnormalities among 5876 younger adult patients treated in the United Kingdom Medical Research Council trials. Blood 116:354-365.

- Jones D, Yao H, Romans A (2010) Modeling interactions between leukemia-specific chromosomal changes, somatic mutations, and gene expression patterns during progression of core-binding factor leukemias. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 49:182-191.

- Bullinger L, Dohner K, Kranz R, Stirner C, Fröhling S, et al. (2008) An FLT3 gene-expression signature predicts clinical outcome in normal karyotype AML. Blood 111: 4490-4495.