Keywords

Amplifiable DNA, Real-time PCR, sterilization, gamma irradiation, electron beam irradiation, Staphylococcus aureus and viability.

Introduction

Sources of ionizing radiation come from electron beams or Xrays generated in electrically driven machines or from gamma rays from radioactive 60Co or 137Cs [1]. High-energy electrons are produced mechanically by means of electric energy in electron accelerators without the use of any radioactive source. Accelerators are switched-off when they are not in use, reducing the risk of fatal failures. Both electron-beam and gamma radiation are widely used for sterilization purposes [2-6]. Electronbeam irradiation has many advantages such as: (a) relatively short process time, (b) in-line process, (c) highly effective, (d) involves few variables, (e) low heat, (f) short release time, (g) low equipment cost and (h) controlled dose [7]. On the other hand, γ-irradiation is used due to its higher penetrating capability and negligible heat production [7,8]. In the medical device industry, ionizing irradiation (mainly γ-radiation) is the second most important cold sterilization method behind ethylene oxide (EtO) sterilization [9]. However, when electron beams and gamma rays from 60Co are compared, similar inactivation levels of vegetative cells of bacteria [10,11] and spores [12] are obtained.

DNA is the principal cellular target governing loss of viability after exposure to ionizing irradiation [13]. The primary mode of action of ionizing radiation is via hydrogen and hydroxyl radi cal molecules resulting from the ionization of water molecules within the target organism. These radicals can disrupt membranes and interfere with the functioning of proteins, but the most significant target within the cell is DNA, where radicals are responsible for strand breakage [14]. Cell death (defined for proliferating cells as loss of reproductive capability) is predominantly induced by double-strand breaks in the DNA, separated by not more than a few base pairs, which can generally not be repaired by the cell [15].

Since its inception in the mid-80s, PCR has become a catalyst that drives biological and medical research. The simplicity of its technique, besides its speed, sensitivity, selectivity, high degree of automation, and the possibility of target quantification have allowed for its integration within fields such as drug discovery, microbial detection, and most notably the diagnosis of both genetic and infectious diseases [16-18]. PCR allows a thermostable DNA polymerase to amplify only a trace amount of nucleic acids into greater than million-fold copies [19,20]. However, PCR is especially susceptible to certain contaminations such as cross contamination among samples, DNA contamination in the laboratory, and carryover contamination between amplified products or primers of the previous PCR [21]. Early users of PCR noticed that carryover contamination could be a significant obstacle owing to the profusion of DNA generated by PCR and the ease with which such DNA can be amplified [22,23]. Since detection and prevention of contamination in PCR are imperative for further experiments, methods to address this have included irradiation of samples with UV light [24,25] before amplification, pretreatment with nucleases [26,27] and modification of oligonucleotide primers [28,29]. Although several studies have investigated the effect of gamma or electron beam irradiation on the viability of microorganisms [30-34], little information is available regarding their effects on microbial DNA with respect to potential for DNA cross-contamination from specimen-to-specimen contact [35-37]. In particular, if gamma or electron beam irradiation effectively eliminates amplifiable DNA, it could be used widely in the laboratory and in clinical practice for prevention of DNA contamination of PCR reaction reagents, laboratory equipments, surgical instruments and containers for specimen collection and transportation.

In relation to this issue, the aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the efficiency of two different types of ionizing radiation, gamma and electron beam irradiation, on the viability of S. aureus pathogen (using quantitative cultures) and on its DNA (using quantitative PCR amplification on the 16S rRNA gene) in an attempt to determine the proper irradiation type and dose to be used for sterilization sufficient not only for viable microbial cells but also for their DNA.

Material and Methods

Bacterial culture

Stock culture of S. aureus ATCC 25923 was frozen at -70°C until studied. Then, it was streaked on Trypton Soya Agar (Oxiod) and incubated for 24hours. 100 ml of sterile Trypton Soya Broth was inoculated with isolated colonies from the agar plate and incubated for 18hours at 37°C. After incubation, the broth was centrifuged (5000g for 10 minutes) and the pellet was resuspended in 100 ml normal saline and adjusted to one McFarland (3X108 cfu/ml).One ml aliquots of bacterial suspension were assayed after exposure to gamma irradiation or electron beam irradiation in three different ways. First, viability of the bacterial cells was evaluated after irradiation of bacterial suspensions. Second, the effect of irradiation was studied on amplifiable free DNA extracted from bacterial cells before irradiation. Third, irradiation effect was studied on amplifiable DNA where viable cells were irradiated first and then the DNA was extracted.

Irradiation sources

60Co Indian Gamma Chamber 4000A, product of Baha Baha Research Center-India with a dose rate of 10KGy/2hours 35minutes 19seconds at the time of experiments, and 1.5 MeV Electron Beam Accelerator (High Voltage Engineering Corp.) with beam current 1mA both located at National Center for Radiation Research and Technology were the gamma irradiation and electron source used respectively.

Assessment of irradiation treatments

For viability of bacterial cells, using either gamma or electron beam irradiation effect, bacterial suspensions were exposed to radiation doses of 0-3 kGy, in increments of 0.2kGy in case of γ-irradiation and at different doses (0.6,1.2,1.6,2.0,2.4,2.8&3 kGy) for electron beam irradiation. After irradiation, serial dilutions were prepared in normal saline, plated on Trypton Soya Agar and incubated for 48hours at 37°C. Viable cells were expressed as mean log10 [c.f.u. (ml suspension)-1] ± SD of triplicates. For DNA, either effect was studied at doses12, 15, 17, 19 &25 kGy using either DNA extracted from bacterial suspensions before irradiation or DNA extracted from irradiated bacterial suspensions, and DNA quantity was determined by quantitative Real -time PCR.

Radiation dose-response curves

Responses to γ and electron beam irradiation were expressed as the logarithm of the ratio of survivors (N/N0), where N represents the mean c.f.u. ml-1 or c.f.u. equivalent ml-1 of irradiated bacterial suspension or DNA respectively, and N0 the mean number of c.f.u. ml-1 or c.f.u. equivalent ml-1 of non-irradiated control. D10 values, defined as the radiation dose (kGy) required to reduce the number of c.f.u. ml-1 or c.f.u. equivalent ml-1 by one log10 were determined by calculating the negative reciprocal of the slope of the linear regression curve [38,39].

DNA extraction and quantitative 16S rRNA gene PCR

DNA was extracted using Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Fermentas) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Real – time PCR (Light Cycler) was used to quantify the 16S rRNA gene. Universal primers (forward primer: 5’-TGGAGAGTTTGATCCTG GCTCAG-3’; reverse primer:5’-TACCGCGGCTGCTGGCAC-3’) were used [40,41]. Each PCR mix consisted of 2μl target DNA added to 18 μl mastermix (Light Cycler® FastStart DNA MasterPlus SYBR Green Ι; Roche Applied Science). Cycling parameters consisted of one cycle at 95°C for 10 minutes (pre-incubation), followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15seconds, annealing at 62 °C for 5 seconds and elongation at 72°C for 20seconds. These PCR conditions were optimized to produce the least nonspecific signal by primer dimers, as evaluated by post amplification melting curve analysis. Mastermix on its own was used as a negative control for PCR. The standard curve was determined by depicting the amplification threshold cycle number (crossing point) against the logarithm of the initial target concentration [42]. Standard curve for S. aureus was generated from five serial dilutions of known quantities of the tested organism (limit of detection, 150 c.f.u. /ml bacterial suspension). DNA quantity was expressed as c.f.u. equivalent (ml bacterial suspension)-1. The 16S rRNA gene was selected because this highly conserved region of bacterial DNA is often used when the infecting agent is not known and the goal is to detect and identify the presence of any bacterium [41]. The 16S rRNA gene is present as multiple copies in the genomes of most bacterial species that belong to the eubacterial kingdom, but is not present in human, viral or fungal genomes. The presence of multiple copies of this target in bacteria increases assay sensitivity when applied to infected human specimens. Broad-range PCR is commonly used in diagnostic microbiology and was therefore chosen for study.

Statistical analysis

PASW statistical software package (V. 18.0, IBM Corp., USA, 2010) was used for data analysis. The following tests were done:

1. Linear Regression Analysis by which the regression equation can be calculated (Y = a + b X). Also, r and r-sq.

2. Descriptive statistics for all trials (the 3 triplicates and their mean for all studied techniques) including mean, SD, CI at 95P.

3. Comparison between the results using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA).

The multiple comparison (Post-hoc test or Least significant difference, LSD) was also followed to investigate the possible statistical significance between each 2 groups.

Results and disscusion

Gamma and electron beam irradiation effects on viability of Staphylococcus aureus cells

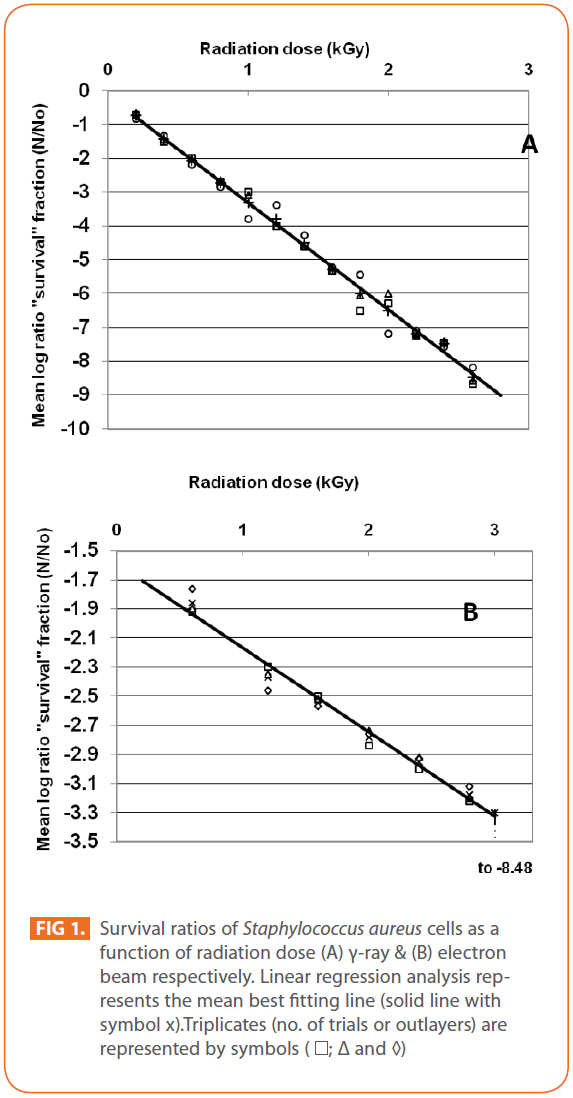

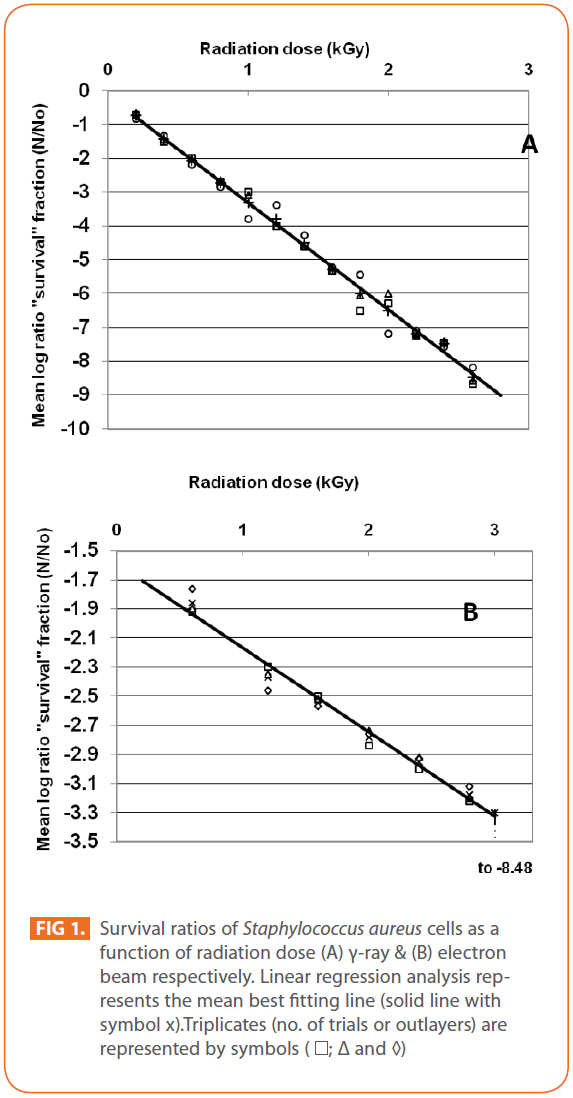

Effects of gamma and electron beam irradiation on the viability of stationary-phase cells of S. aureus are shown in (Figures 1A & 1B), respectively. It is clear that, ionizing radiation treatment effectively decreased the viable microbial population with increasing radiation dose and in particular, the D10-value for S. aureus obtained by electron beam irradiation was higher than that using γ-irradiation source, which means that, gamma irradiation was more effective than electron beam irradiation in reducing viability of the test pathogen. Electron beam, unlike gamma rays, has limited penetration depth [43], which may affect microbial inactivation. Bacterial viability was abrogated at (2.6kGy) and (3kGy) and D10- values (kGy) ± SD for bacterial cells were (0.3155 ± 0.0061) & (1.7307 ± 0.0498), CI 95P were (Min = 0.0151 and Max. = 0.3306) & (Min. = 0.1234 and Max. = 1.855), r (-0.9990) & (-0.9925) and r2 (0.9979) & (0.9851) for γ- and electron beam irradiation respectively (P = 0). 3 kGy sterilized stationary-phase population of S. aureus by gamma and electron beam irradiation. For electron beam irradiation, the survival ratio decreased linearly with increasing radiation dose, and then deviated from linearity at dose of 3kGy, (Figure 1B). The calculated D10- values in this study were comparable to those reported by others, ranging from 0.20 to 0.71 kGy with respect to γ-irradiation [44-46]. The relative resistance of microorganisms to irradiation was summarized by Monk et al. [47]. Vegetative cells of bacteria are very sensitive to ionizing radiations, with D10- values usually lower than 1 kGy with some remarkable exceptions, such as Deinococcus radiodurans, with D10 -values greater than 10 [48]. Radiation susceptibility of cells is affected by different factors such as replication rate, medium composition, temperature, amount of DNA and the ability to repair radiation induced DNA damage [49]. Inactivation of microorganisms by electron-beam irradiation comes from the inhibition of DNA repair mechanism by increased energy demand of homeostasis on the cell [50,51]. Also, Clauditz et al. [52] reported that staphyloxanthin, a membrane-bound carotenoid of S. aureus, can play a radical scavenger in the defense against damage by reactive oxygen substances, resulting into relatively radiation-resistant. S. aureus is a clinically important pathogen in implant industry and device-associated infections [53], while most studies focused on microorganisms important in food preservation [46,51].

Figure 1: Survival ratios of Staphylococcus aureus cells as a function of radiation dose (A) γ-ray & (B) electron beam respectively. Linear regression analysis represents the mean best fitting line (solid line with symbol x).Triplicates (no. of trials or outlayers) are represented by symbols ( ; Δ and ◊)

Gamma and Electron beam irradiation effects on amplifiable DNA of Staphylococcus aureus with relation to their effects on cell viability

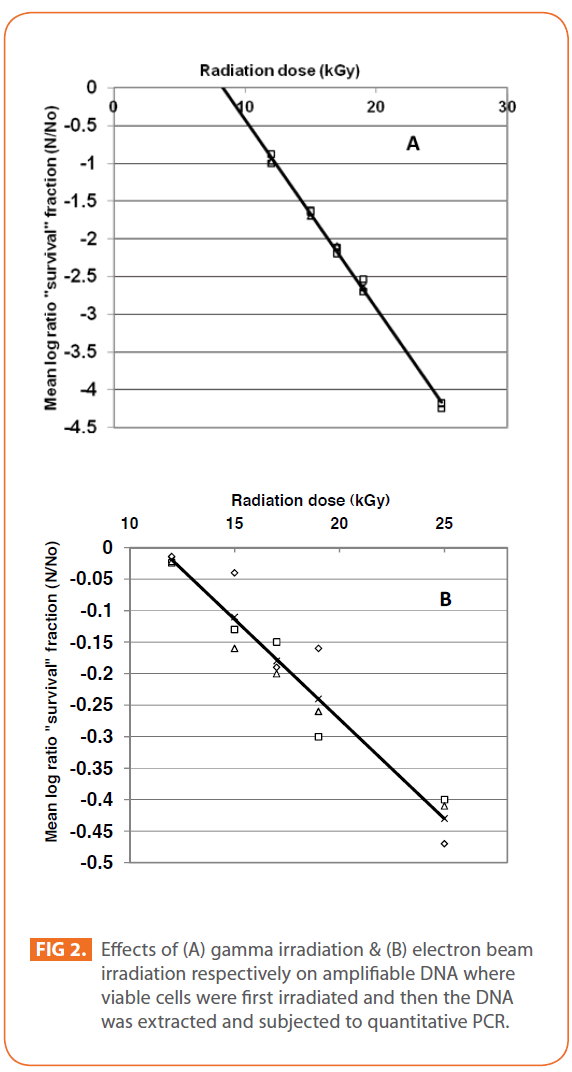

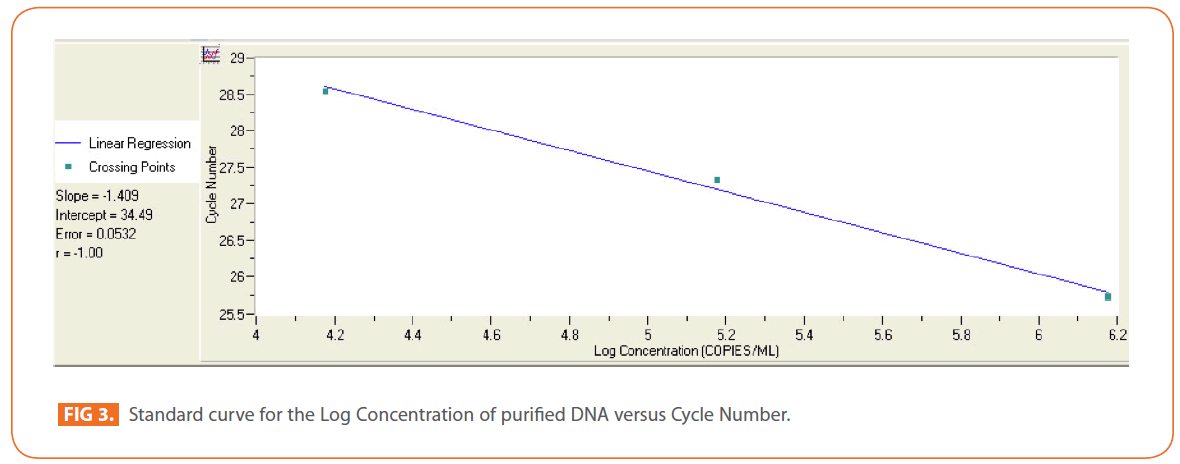

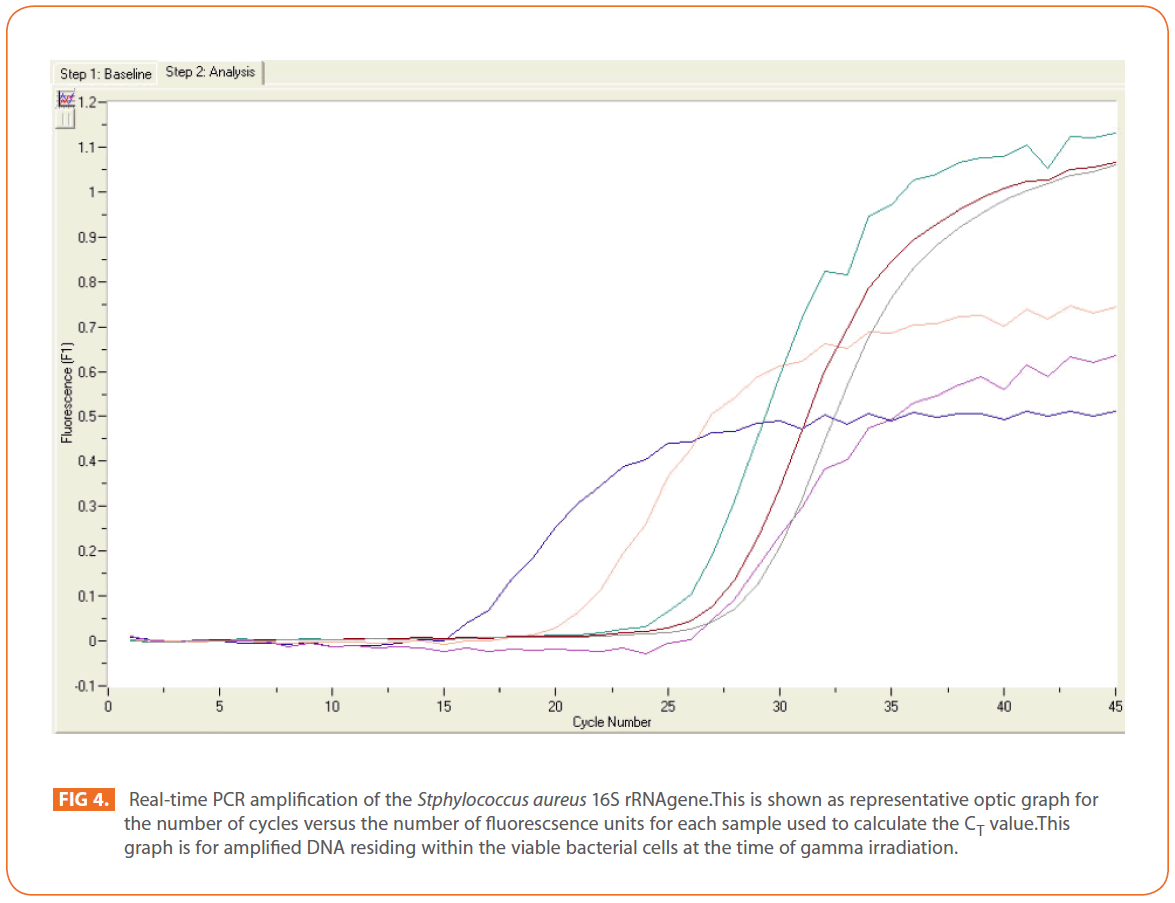

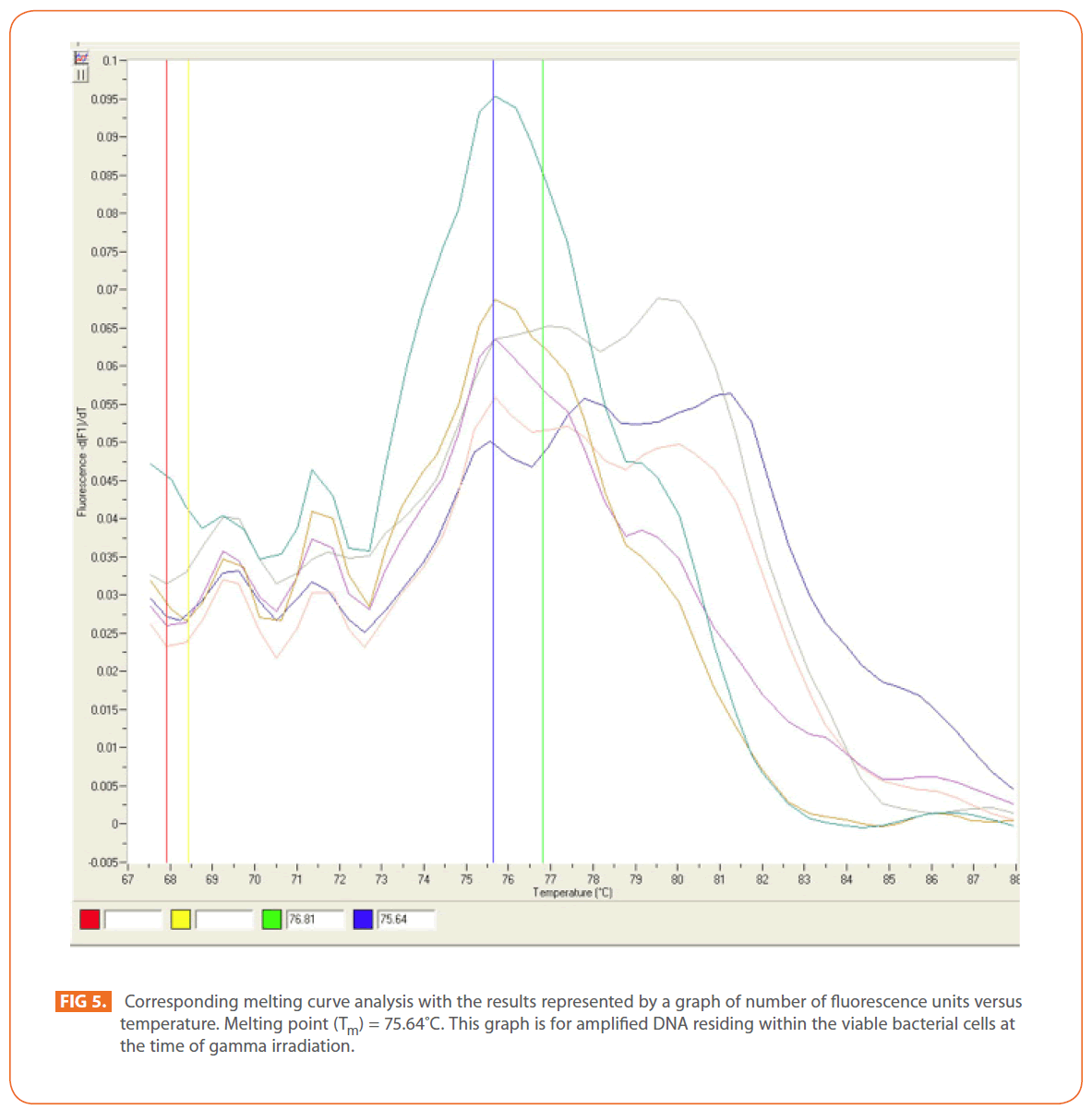

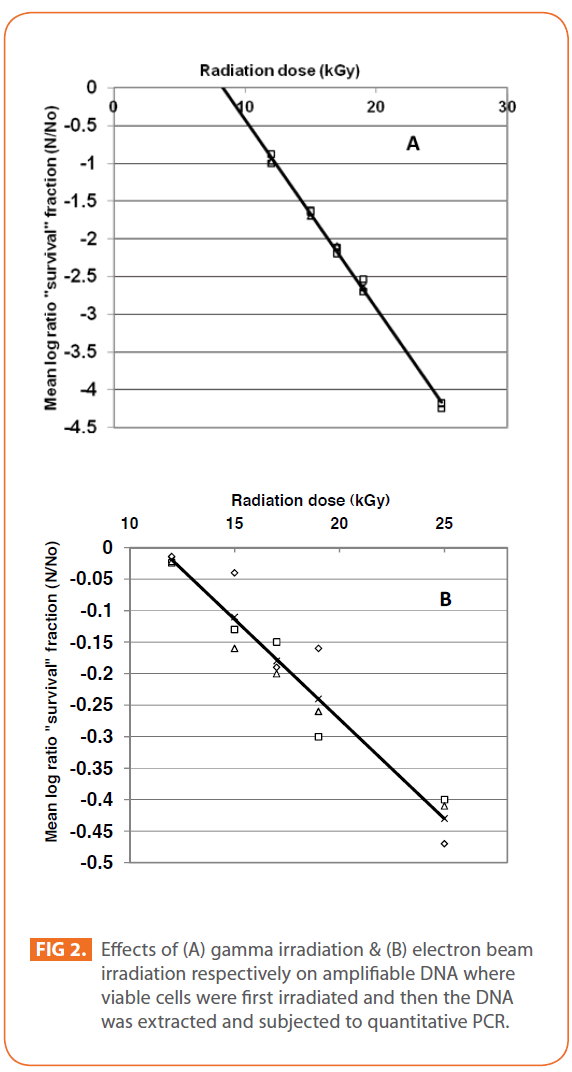

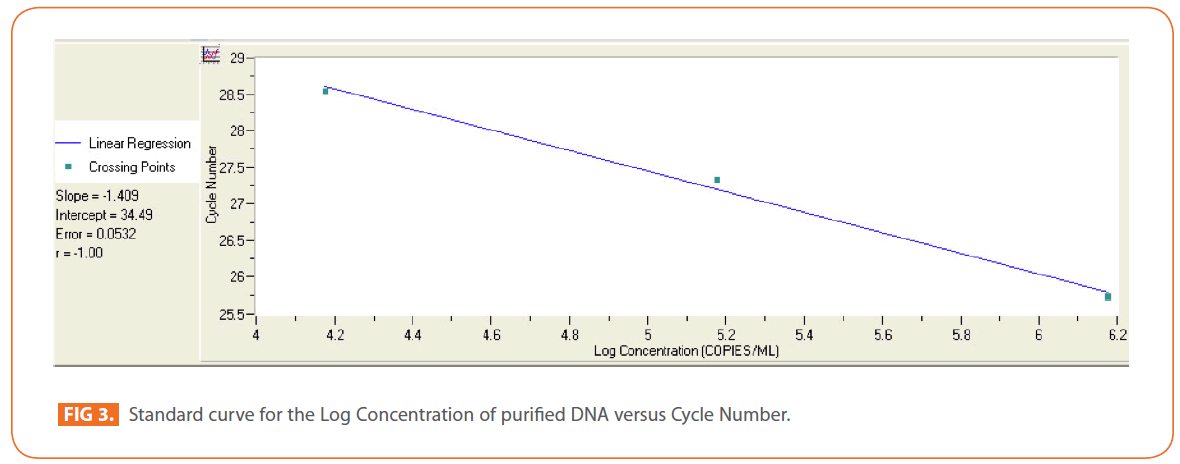

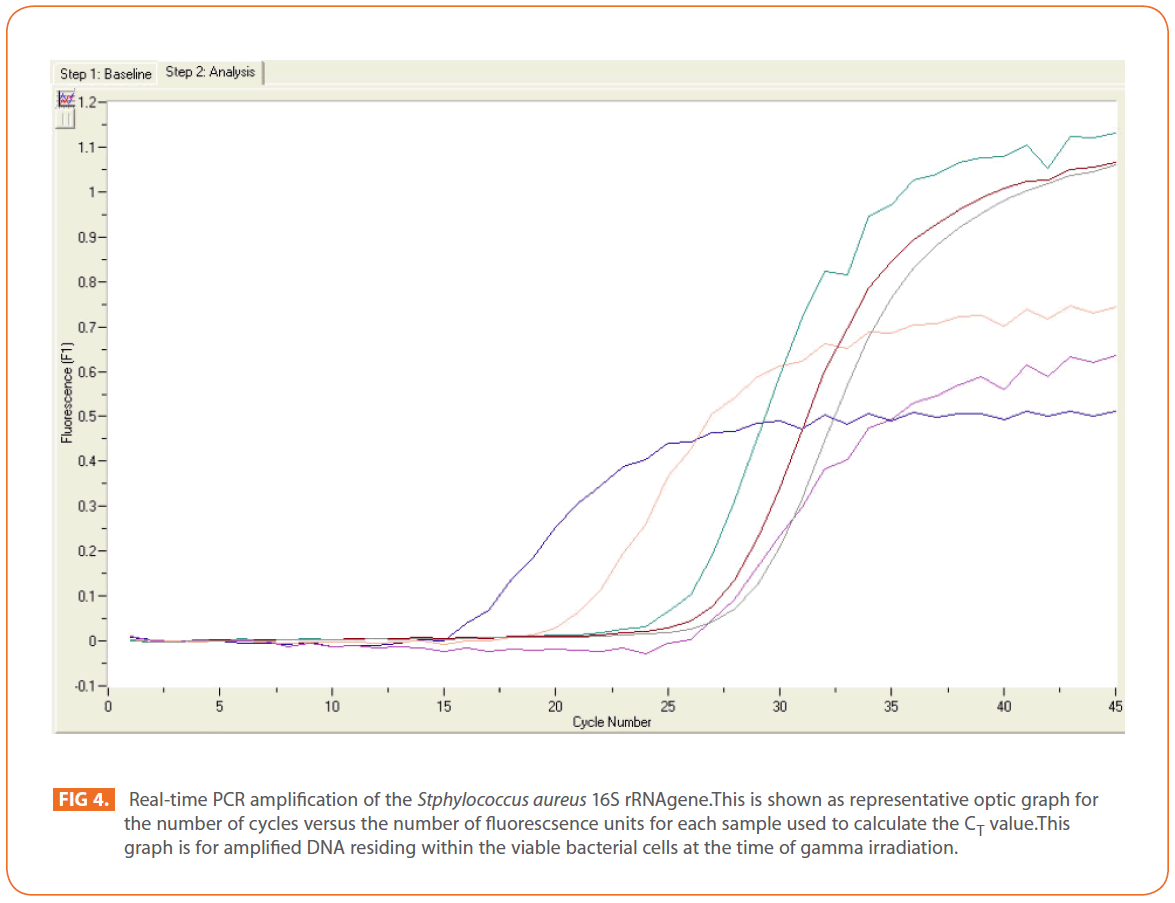

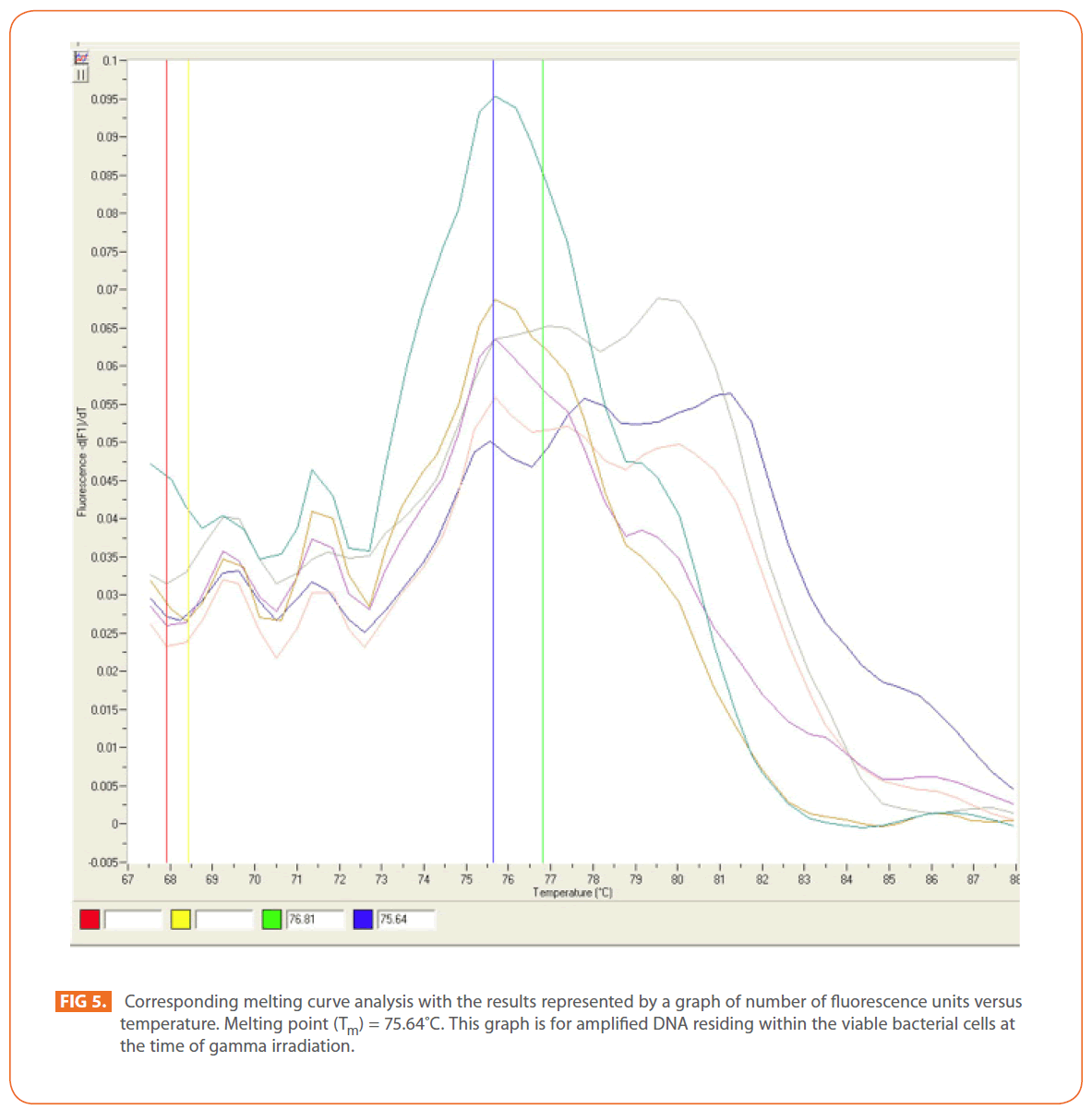

The effects of gamma and electron beam irradiation on S. aureus amplifiable DNA where viable cells were first irradiated and then the DNA was extracted and subjected to quantitative PCR are shown in (Figures 2A & 2B) , respectively. It is clear that, D10- value was lower for gamma irradiation compared to that of electron beam. D10- values (kGy) ± SD were (3.9888 ± 0.0524) & (32.167 ± 3.6808), CI 95P were (Min = 0.1303 and Max. = 4.1194) & (Min.= 23.0291 and Max.= 41.3049), r (-0.9996) & (-0.9999 ) and r2 (0.9992) & (0.9997 ) respectively. LSD (Mean– Diff. = -28.1779, P = 0 highly significant). (Figure 3) represents the standard curve for the Log concentration of purified DNA versus cycle number. Real- time PCR amplification of the S. aureus 16S rRNA gene for DNA residing within the viable bacterial cells at the time of gamma irradiation is shown in (Figures 4 & 5).

Figure 2: Effects of (A) gamma irradiation & (B) electron beam irradiation respectively on amplifiable DNA where viable cells were first irradiated and then the DNA was extracted and subjected to quantitative PCR.

Figure 3: Standard curve for the Log Concentration of purified DNA versus Cycle Number.

Figure 4: Real-time PCR amplification of the Stphylococcus aureus 16S rRNAgene.This is shown as representative optic graph for the number of cycles versus the number of fluorescsence units for each sample used to calculate the CT value.This graph is for amplified DNA residing within the viable bacterial cells at the time of gamma irradiation.

Figure 5: Corresponding melting curve analysis with the results represented by a graph of number of fluorescence units versus temperature. Melting point (Tm) = 75.64?C. This graph is for amplified DNA residing within the viable bacterial cells at the time of gamma irradiation.

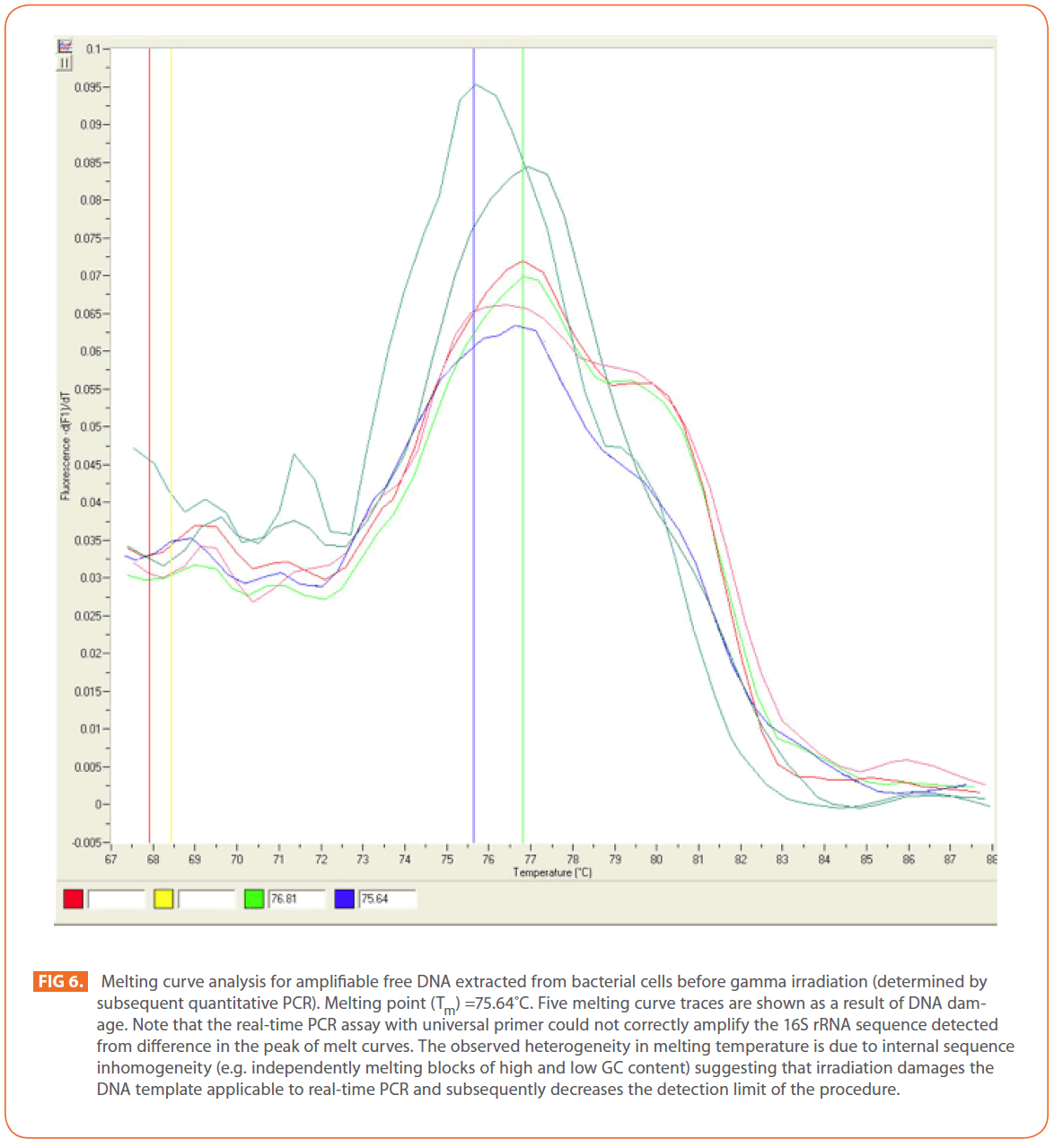

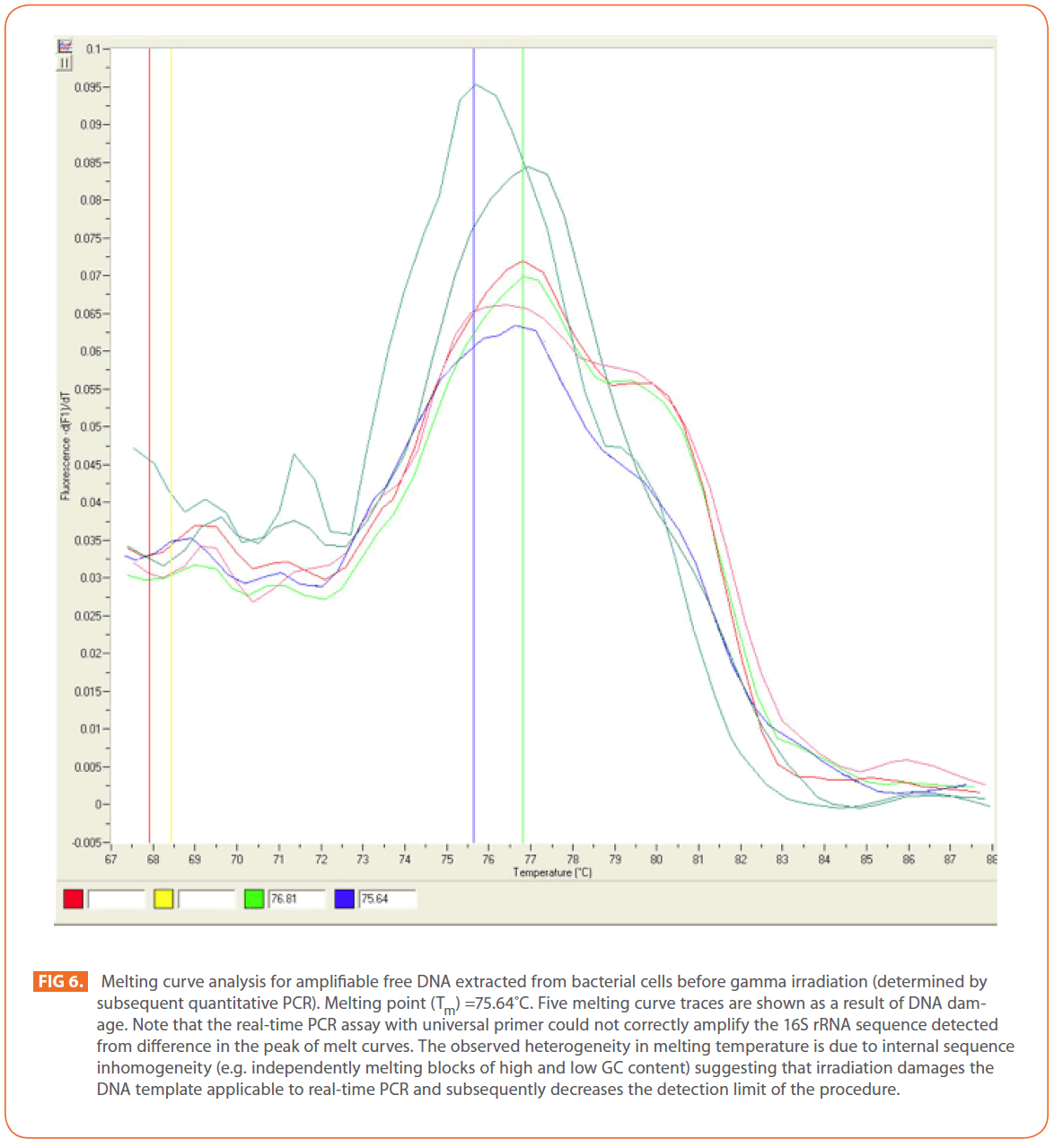

In contrast, irradiation of DNA extracted from bacteria before irradiation showed different effect. Gamma irradiation at the tested doses (12-25 kGy) damaged the DNA template applicable to real-time PCR and subsequently decreased the detection limit of the procedure. In real—time PCR the melting temperature of a DNA double helix depends on its base composition, all PCR products for a particular primer pair should have the same melting temperature, but if the peaks are not similar, this might suggest mispriming (PCR products made due to annealing of the primers to complementary, or partially complementary sequences on non-target DNAs), or some other problem [37]. Melting curve analysis can be used in known and unknown (new) mutation analysis as a new mutation will create an additional peak or change the peak area [54]. (Figure 6) shows an increase in melting curve temperatures (Tm) as a result of DNA damage (mutation).

Figure 6: Melting curve analysis for amplifiable free DNA extracted from bacterial cells before gamma irradiation (determined by subsequent quantitative PCR). Melting point (Tm) =75.64?C. Five melting curve traces are shown as a result of DNA damage. Note that the real-time PCR assay with universal primer could not correctly amplify the 16S rRNA sequence detected from difference in the peak of melt curves. The observed heterogeneity in melting temperature is due to internal sequence inhomogeneity (e.g. independently melting blocks of high and low GC content) suggesting that irradiation damages the DNA template applicable to real-time PCR and subsequently decreases the detection limit of the procedure.

DNA is considered the critical target of ionizing radiation [13,55], which forms three different free radicals through the radiolysis of water: the OH radical (·OH), the solvated electron (eeq), and the H-atom (H·) [13]. In a solution, radiation-induced damage to DNA is effectively caused by ·OH, which triggers the formation of single- and double-strand breaks, inducing global changes in DNA conformation such as a loss of superhelicity or chromosome circularity [56,57]. The results obtained indicated that, gamma irradiation of S. aureus at the tested doses from 12 to 25 kGy could eliminate amplifiable DNA extracted before irradiation which could be attributed to the failure of DNA to amplify due to DNA degradation, such as alteration in primer binding sites or reduction of DNA into fragments smaller than the target. The obtained results were compared with Trampuz et al. [58] who found that , gamma irradiation did not eliminate amplifiable DNA at radiation dose up to 12kGy for Staphylococcus epidermidis and Escherichia coli.

Irradiation results in DNA damage, including base modification, abasic sites, and strand breaks [13,59]. Because DNA lesions are capable of stopping a thermostable polymerase on the DNA template [37,60], an increase in lesions will result in decreased PCR amplification of the target sequence. Meanwhile, free amplifiable DNA (extracted before irradiation) irradiated with accelerated electrons at the same doses of gamma irradiation was reduced with negligible change in quantity with increasing dose. Even at the highest radiation dose tested (25kGy), a reduction in the quantity of amplifiable DNA corresponding to just -1.126 ± 0.0087 log10 (c.f.u. S. aureus ml-1). The DNA quantity after amplification of normal saline without bacteria (negative control) was below the detection limit. We have demonstrated that, gamma and electron beam irradiation of viable S. aureus cells has smaller effect on amplifiable 16S rRNA genes than dose irradiation of extracted DNA. In addition, DNA in viable cells may be more resistant to irradiation than free DNA because of low molecular mass scavengers that mop up free radicals in the cells, physical protection of DNA by packaging in cells and/or cellular repair of damaged DNA [15].

In dying cells, DNA fragmentation may also occur because of the action of nucleases. Irradiated bacteria may be more easily lysed than non-irradiated bacteria; consequently, larger amounts of extracted DNA would be available for PCR [58].

By studying the correlation between the two different types of ionizing radiation used in this study, gamma and electron beam irradiation, and their effects on viable bacterial cells and on cell-associated DNA; highly significant correlation was found (Mean = 10.3909, SD = 14.1439, F = 169.872, P = 0).

Conclusion

This study indicates that gamma irradiation at doses from (12- 25kGy) can be used for elimination of free DNA contamination of PCR reaction components or laboratory equipments compared to use of accelerated electrons at the same doses, while it has smaller effect on amplifiable DNA when this DNA is present in microbial cells. The inability of gamma irradiation to eliminate microbial DNA in viable cells needs to be taken into account in clinical practice as molecular amplification techniques are increasingly used in microbiological diagnostic applications.

181

References

- Alipio BC, David FC, Isabel RS, Juan CNM. Manuel AE. Comparison of batch, stirred flow chamber, and column experiments to study adsorption, Desorption and transport of carbofuran within two acidic soils. Chemosphere. 2012; 88(1): 106-120.

- Arnaud B, Richard C, Michel S. A comparison of five pesticides adsorption and Desorption processes in thirteen contrasting field soils. Chemosphere. 2005; 61(5): 668-676.

- Chunxian W, Jin-Jun W, Su-Zhi Z, Zhong-Ming Z. Adsorption and Desorption of Methiopyrsulfuron in Soils. Pedosphere. 2011; 21(3): 380-388.

- Chunxian W, Suzhi Z, Guo N, Zhongming Z, Jinjun W. Adsorption and Desorption of herbicide monosulfuron-ester in Chinese soils. J Environ Sci. 2011; 23(9): 1524-1532.

- Christine MFB, Josette MF. Adsorption-desorption and leaching of phenylurea herbicides on soils. Talanta. 1996; 43(10): 1793-1802.