Keywords

Hepatitis-B virus; Perinatal transmission; Highly viremic women; Lamivudine; Tenofovir; Late pregnancy

Introduction

Chronic Hepatitis-B virus (HBV) infection is endemic in some regions, including Asian Pacific where Vietnam is situated, with current estimates of 400 million chronically infected individuals worldwide [1-5]. HBV infection early in the life confers a high risk of chronicity, thus establishes entrenched patterns of endemicity because of repeated cycles of mother-to-infant transmission [6- 14]. In high endemicity regions such as Asia, infants born to moth-ers positive for both HBsAg and HBeAg have a 70-90% chance of acquiring perinatal HBV infection, and a great majority of them (90-95%) will become chronic HBV carriers [2,6,9-14]. Good practice of vaccination to children born to HBsAg positive women prevents mother-to-child transmission in 80-95% of cases and has critically reduced the incidence of HBV in childhood worldwide [2-4,6-8]. However, estimates of the risk of HBV transmission despite good immunoprophylactic practices vary between 15-25% [6,14-24] and even up to 39% [17]. A high viral level of HBV in mothers is the most important determinant of this prophylaxis failure [6,9-16]. Prophylactic therapy during pregnancy is nowa days well established and has shown good efficacy in reducing mother-to-infant transmission of HBV [6], and safety for both mothers and babies using lamivudine, telbivudine, and recently tenofovir [22-32]. In Vietnam, chronic HBsAg carriage prevalence varies between 10-20% in general population and around 2.7% in children under five despite well conducted active prophylaxis against HBV incorporated into the national program of vaccination since 1997 [5]. In the present article, we reported results of a multicenter, randomized open-label study evaluating whether lamivudine and tenofovir given during late pregnancy to highly viremic mothers could comparatively reduce HBV transmission to their infants. Our purpose was to find a prophylactic agent of first choice in view of cost-effectiveness in public health, given the large population and high rate of HBV infection in a low-income country.

Subjects and Methods

Eligible subjects included pregnant women aged ≥18 years with chronic HBsAg positive (by ELISA technique) and serum HBV DNA≥107 copies/mL (COBAS® AmpliPrep/COBAS® TaqMan® HBV Test, v2.0, Roche Diagnostics, lower limit of detection of 69 copies/mL) at screening time (28-30 weeks of gestation) in four medical centres in Hanoi (National Hospital of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Hanoi Municipality Hospital of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Bachmai Tertiary University Hospital and International Vietnam-France Hospital in Hanoi). Subjects were excluded if they were co-infected with hepatitis C virus or with HIV, had received any antiviral treatment, or had any sign of hepatic, renal or hematologic disorders, abnormal fetal development, or gravidic toxemia. Eligibly enrolled pregnant women were randomized (using random table) into two groups, treated from week 32 of gestation to week 4 postpartum, by either lamividine (Zeffix®, Glaxo-SmithKline, UK, 100 mg daily) or tenofovir (Gentino-®, Standa, Germany, 300 mg daily).

The primary efficacy endpoint was indicated by the HBV perinatal transmission rate defined by HBsAg presence in children’s blood at week 52.

The secondary efficacy endpoints included: (1) rates of HBsAg and HBV DNA presence in children at birth, (2) mean difference (MD) in maternal HBV DNA levels between starting point (Baseline) and at delivery (Birth), (3) the rate of secondary resistance to drugs in use after 8 weeks of treatment.

Additionally, safety profiles included adverse events in treated mothers and their infants, death and laboratory abnormalities.

Assuming lamivudine would further reduce at least 50% of HBV perinatal transmission defined by HBsAg positivity in infants at week 52 (18% in treated groups versus 39% in placebo control groups) as reported by Xu et al. [17], while tenofovir was supposed to attain the same efficacy as telbivudine by reducing at least 80% of HBV perinatal transmission (0% in treated groups versus 8% in untreated control group) as reported by Han et al. [20], we planned to enroll at least 84 subjects to provide >90% power to be able to detect a difference in these proportions at week 52 under tenofovir versus lamivudine treatment, based upon the chi-square test.

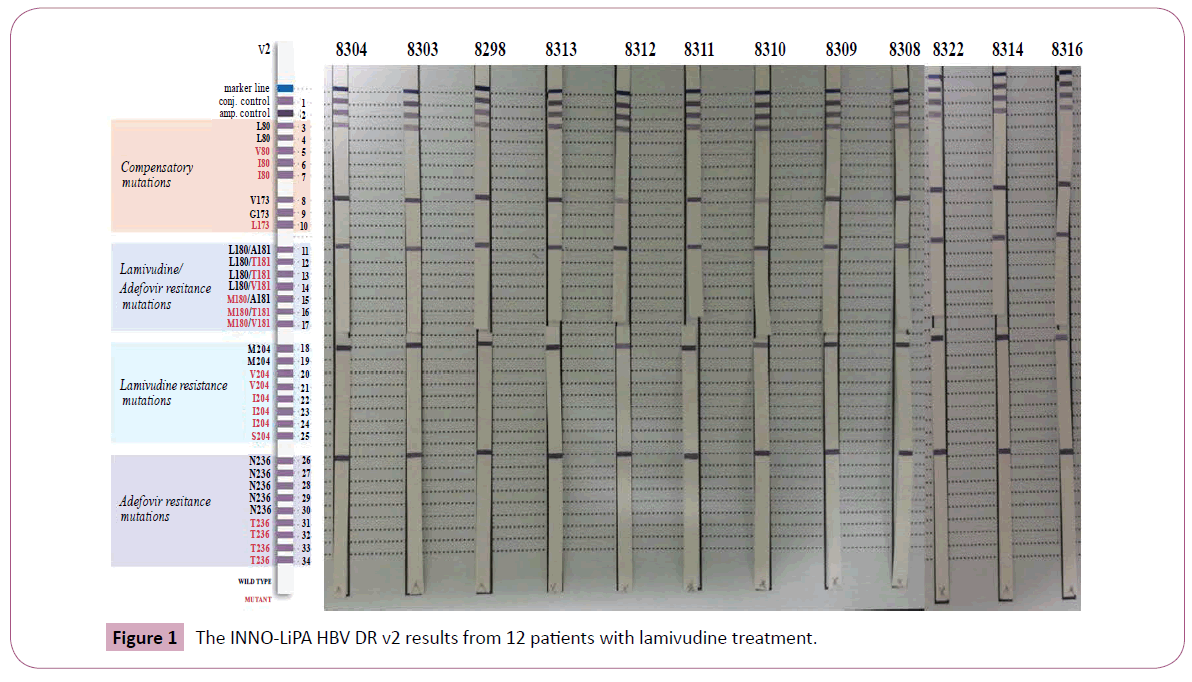

Mothers were seen at week 28 (Screening) and at week 32 (Baseline) of gestation, then every two-week interval until delivery (Birth), and finally at week 4 pospartum (Endpoint of treatment) for general and prenatal health checks, treatment observance control, and adverse events of drugs under treatment. Their infants were vaccinated with recombinant HBV vaccine (Engerrix-B®, Glaxo-SmithKline) by standard schedule of four doses (within 24 h of birth, week 4, week 8 and week 48) without HBIg combination. Quantification of HBsAg and HBV DNA levels was performed at a WHO’s reference laboratory of Virology Division, Microbiology Department, Bachmai Hospital, using the DNA assay described above. Viral resistance to tenofovir and lamivudine was assessed in suspected mothers, i.e. either mothers with weak viral response to treatment (HBV DNA reduction <2 log10 copies/mL), or those whose newborn showed HBsAg presence in the cordon blood. The INNO-LiPA HBV DR v2 and v3 Kits (reverse hybridization based line probe assay, Innogenetics, Belgium) were used (AlphaBio Labo, European Hospital, Marseille, France) to determine the resistance to lamuvidine and tenofovir, respectively.

Infants were assessed at birth (within 24 h of delivery), at every four weeks for the first three months, then every three months, and finally at 52 weeks. Points of assessment include physical and mental development, drug adverse events. The tests for quantitative HBV DNA titer and other HBV markers, including HBsAg, HBeAg, anti-HBe, anti-HBs and anti-HBc (using umbilical cordon blood at birth, then venous blood at month 6 and 12) were done at birth, then at 6 and 12 months of age.

All participants signed a written informed consent; the study protocol was reviewed and approved by Ethics Committees of Ministry of Technology and Science, of Ministry of Health, of Hanoi Medical Univesity, and of each participating institution.

Efficacy endpoints and safety profiles were in all participant mothers and their children (intention-to-treat analysis) if the difference in dropout rate in two study subgroups was <10% (≤4 mother-infant pairs). In case of higher difference in droupout rate, it would be calculated only in fully participating motherinfant pairs (per protocol analysis). Statistical significance was set up at the 0.05 level. All p values were 2-tailed. Data were analyzed using SPSS software (SPSS® Statistics for Windows™ version 20.0 Copyright IBM Corp, 2011).

Results

Between January 2011 and December 2013, amongst 864 chronic HBsAg positive pregnant women enrolled in the study, 112 (12.96%) were highly viremic (>107 copies/mL), of them 96 (85.7%) signed informed consents to participate in the study, forming the intention-to-study population. Finally, per-protocol population for analysis consisted of only 82 (85.5%) motherchild pairs who completed the study protocol up to 52 weeks of life of infants; 14 cases (14.5%) were excluded from analysis, including withdrawal in 11 pairs (early withdrawal or medication stop before delivery in 8 pregnant women, and late withdrawal or test refusal in 3 children) and pending for delivery in 3 cases. HBV DNA levels at baseline (week 32 of gestation) were very high in our study population, with a viral load >108 copies/mL in 71/82 (86.6%) pregnant women (>9.89 × 108 copies/mL in 15 cases or 18.3%, >6.4 × 108 copies/mL in 32 cases or 39.0%, and >1-6.4 × 108 copies/mL in 24 cases or 29.3%); a viral load of 1-107 copies/ mL was seen only in 11 cases (13.4%).

The proportions of HBsAg positivity and detectable HBV DNA in the blood of 82 babies born to mothers under either tenofovir or lamivudine were summarized in Table 1. At birth, 16/49 (32.7%) and 4/49 (8.2%) infants of the tenofovir-treated mothers were HBsAg positive and HBV DNA positive compared to 5/33 (15.2%) and 3/33 (9.1%) infants in the lamividine-treated mothers (p = 0.075 and 0.591, respectively). The total positive proportions of HBsAg and HBV DNA at birth in infants of treated mothers were then 21/82 (25.6%) and 7/82 (8.5%), respectively. At six months of age, among 16/49 infants born to mothers under tenofovir who were HBsAg positive at birth, only one remained HBsAg positive with high level of HBV DNA (6.4 × 108 copies/mL), while none of the 33 infants born to mothers under lamivudine was HBsAg positive and HBV DNA detectable.

Serum

HBsAg and HBV DNA in infants |

Proportions of infants with mothers under treatment |

Tenofovir

(n = 49) |

Lamivudine

(n = 33) |

Total

(n = 82) |

p |

At

birth |

HBsAg |

(-) |

33 (67.3) |

28 (84.8) |

61 (74.4) |

0.075 |

| (+) |

16 (32.7) |

5 (15.2) |

21 (25.6) |

|

| HBV DNA |

(-) |

45 (91.8) |

30 (90.9) |

75 (91.5) |

0.591 |

| (+) |

4 (8.2) |

3 (9.1) |

7 (8.5) |

|

At 6 months

of age |

HBsAg |

(-) |

48 (98.0) |

33 (100) |

81 (98.8) |

|

| (+) |

1 (2.0) |

0 |

1 (1.2) |

NC* |

| HBV DNA |

(-) |

48 (98.0) |

33 (100) |

81 (98.8) |

|

| (+) |

1 (2.0) |

0 |

1 (1.2) |

NC* |

At 12 months

of age |

HBsAg |

(-) |

48 (98.0) |

32 (97.0) |

80 97.4) |

>0.05 |

| (+) |

1 (2.0) |

1 (3.0)# |

2 (2.4) |

|

| HBV DNA |

(-) |

48 (98.0) |

32 (97.0) |

80 97.4) |

>0.05 |

| (+) |

1 (2.0) |

1 (3.0)# |

2 (2.4) |

|

*NC: Not calculated; #Horizontal infection case

Table 1: Serum HBsAg, HBeAg and HBV DNA status at birth, 6 months and 12 months of age in infants born to mothers under either tenofovir or lamivudine.

At 12 months of age, the unique case with HBsAg positive and HBV DNA detectable at six months remained HBsAg positive with higher level of HBV DNA (8.4 × 108 copies/mL). In overall, the rate of HBV perinatal transmission among our per-protocol population was 1/82 (1.2%). However, among the 33 infants born to mothers under lamivudine, surprisingly, we noted a case who was free from HBsAg and HBV DNA at birth and at six months of age became HBsAg positive and HBV DNA detectable with high viral load (6.4 × 108 copies/mL). Therefore, we considered this case as horizontally infected after 6 months of age.

The mean maternal serum HBV DNA level of 5.09 × 108 ± 3.19 × 108 at baseline was reduced to 1.13 × 106 ± 3.91 × 106) at birth (during the labor). Therefore, the mean HBV DNA reduction after 8 weeks of treatment was of 5.08 × 108 ± 3.17 × 108, with undetectable HBV DNA noted in 2/32 mothers under lamivudine (6.6%). The correlation between the HBV DNA decrease stratified by log10 in mothers under antivirals and the HBV DNA status in umbilical blood of offspring was presented in Table 2.

| HBV DNA reduction (log10) |

Tenofovir

(n = 49) |

Lamivudine

(n = 33) |

Total

(n = 82) |

p |

| 1-2 log10, n (%) |

2 (4.1) |

12 (36.4) |

14 (17.1) |

0.008 |

| 3 log10, n (%) |

15 (30.6) |

13 (39.4) |

28 (34.1) |

0.705 |

| 4 log10, n (%) |

27 (51.1) |

5 (15.2) |

32 (39.0) |

<0.001 |

| 5-8 log10, n (%) |

5 (10.2) |

3 (9.0) |

8 (9.8) |

0.980 |

Table 2: HBV DNA reduction levels (copies/mL) stratified by log10 between baseline and birth in mothers treated by lamivudine or tenofivir.

None of the 8 infants born to mothers with a strong viral load reduction after treatment (5-8 log10 copies/mL) nor the 14 born to mothers with slight viral load reduction (1-2 log10 copies/mL) was HBsAg positive or HBV DNA detectable at birth. However, amongst the 60 offspring’s of mothers whose viral loads decreased by 3-4 log10, seven were HBsAg positive and HBV DNA detectable at birth, and one remained positive at 6 and 12 months (the unique case of perinatal transmission in the study). There was a tendency of higher rate of detectable HBV DNA in infants born to mothers under lamivudine than in those born to mothers under tenofovir, but this tendency did not attain statistical significance (p>0.05).

In mothers under lamivudine, HBV DNA decrease levels aggregated in 1-3 log10 (25/33 or 75.8%), while in mothers under tenofovir, it aggregated in 3-4 log10 (42/49 or 81.7%). The reduction of HBV DNA levels aggregating in 1-2 log10 was significantly higher in mothers under lamivudinein than mothers under tenofovir (36.4% compared to 4.1%, p<0.01), while HBV DNA reduction aggregating in 4 log10 was far higher in mothers under tenofovir than in mothers under lamivudine (51.1% compared to 15.2%) (p<0.001) (Table 3)

| Decreased HBV DNA in mothers |

HBV DNA in cordon blood |

Tenofovir

n (%) |

Lamivudine n (%) |

Total

n (%) |

p |

| 1-2 log10, n (%) |

(-) |

2 (100) |

12 (100) |

14 (100) |

|

| |

(+) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

NC* |

| 3 log10, n (%) |

(-) |

14 (93.3) |

11 (84.6) |

25 (89.3) |

|

| |

(+) |

1 (6.7) |

2 (15.4) |

3 (10.7) |

>0.05 |

| 4 log10, n (%) |

(-) |

24 (88.9) |

4 (80.0) |

28 (87.5) |

|

| |

(+) |

3 (11.1) |

1 (20.0) |

4 (12.5) |

>0.05 |

| 5-8 log10, n (%) |

(-) |

5 (100) |

3 (100) |

8 (100) |

|

| |

(+) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

NC* |

*NC: Not calculated.

Table 3: Correlation between HBV DNA decrease by log10 copies/mL in mothers under antivirals and HBV DNA status in umbilical blood of offspring.

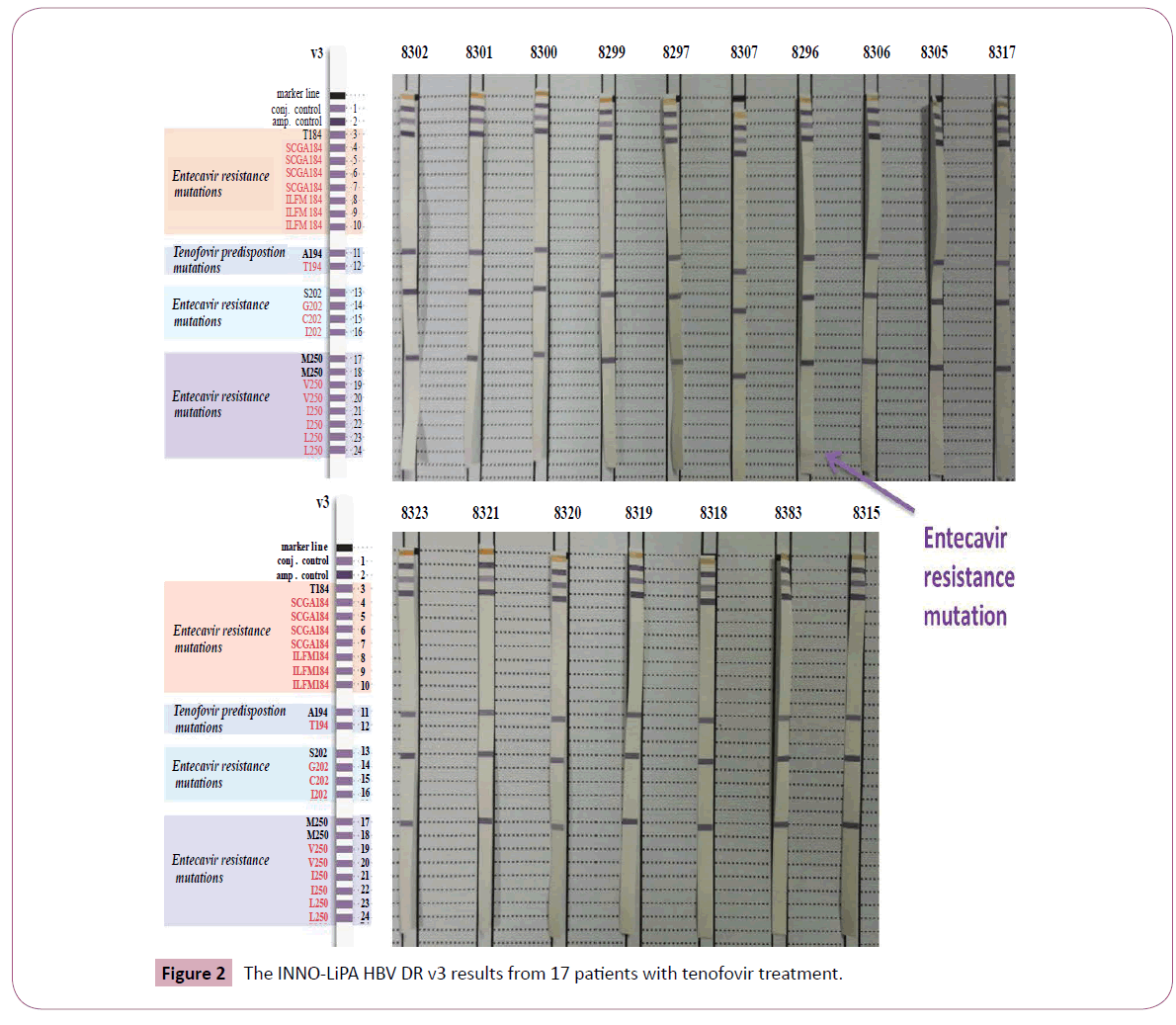

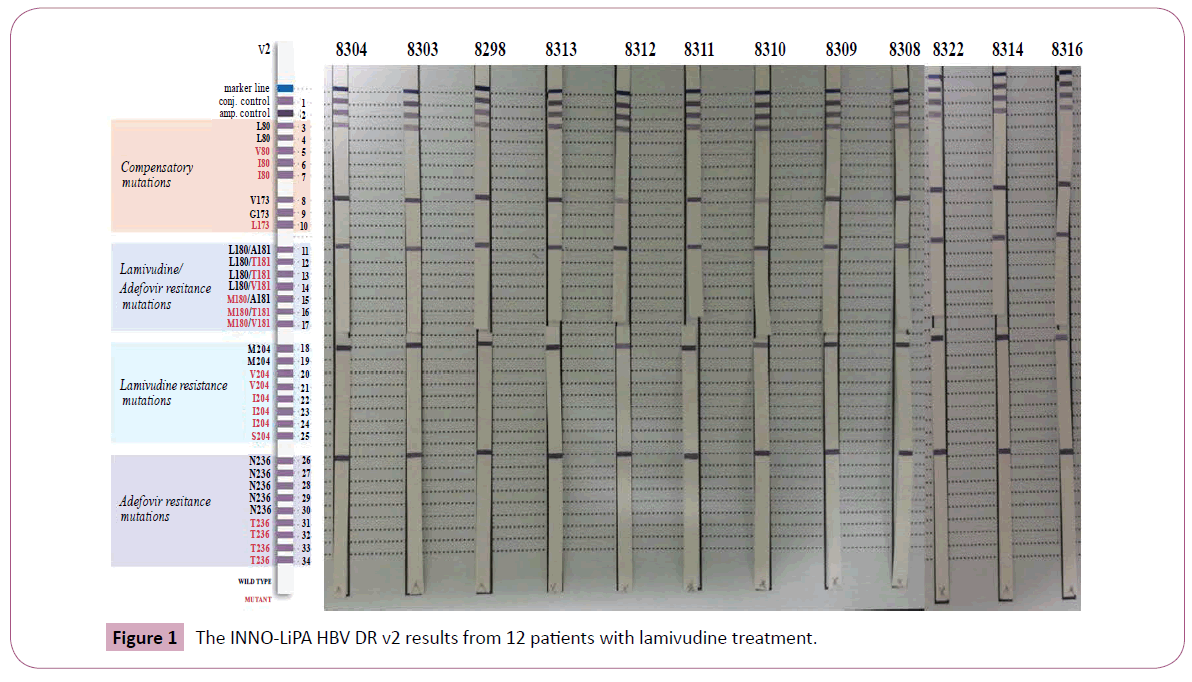

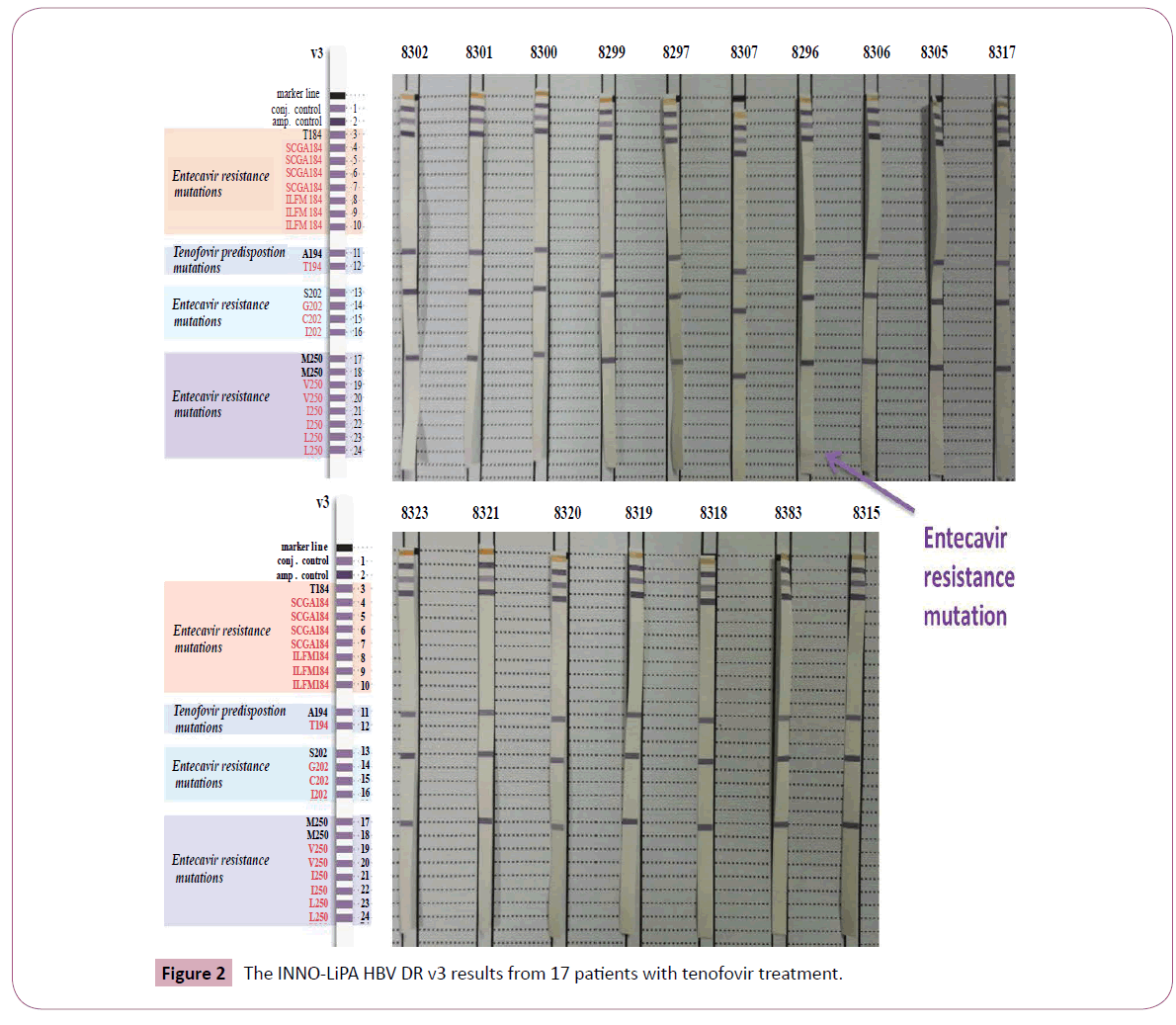

Viral resistance to lamivudine and tenofovir was explored in 29 mothers, in whom either HBV DNA reduction after treatment was less than 2 log10 copies/mL (8 cases), or HBsAg was positive in cordon blood of the newborn (21 cases). The results by INNOLiPA HBV DR v2 from 12 patients with lamivudine treatment and by INNO-LiPA HBV DR v3 from 17 patients with tenofovir treatment were presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2. None of these 29 blood samples exhibited viral resistance mutation to antivirals in use. Nevertheless, an entecavir resistance mutation had been observed in a mother treated by tenofovir.

Figure 1: The INNO-LiPA HBV DR v2 results from 12 patients with lamivudine treatment.

Figure 2: The INNO-LiPA HBV DR v3 results from 17 patients with tenofovir treatment.

Incidence and frequency of drug adverse events in pregnant women under treatment were described in Table 4. Clinically, we observed 24 events occurred in 10 pregnant women under treatment, including 7/49 mothers under tenofovir (14.3%) and 3/33 mothers under lamivudine (9.1%) (p>0.05). Most frequent symptoms were nausea and fatigue, followed by loss of appetite, abdominal floating, diarrhea and abdominal pains. Most events occurred in the first two weeks of treatment (19/24 events) with a duration <3 days in 4 cases, 3-10 days in 4 cases, and 11-21 days in 2 cases.

| Symptoms |

Tenofovir (7/49) |

Lamivudine (n=3/33) |

Total |

| Digestive |

| Nausea |

4 |

1 |

5 |

| Floating |

1 |

2 |

3 |

| Diarrhea |

2 |

1 |

3 |

| Abdominal pains |

2 |

0 |

2 |

| General |

| Severe fatigue |

3 |

2 |

5 |

| No appetite |

2 |

1 |

3 |

| Urticaria/itching |

2 |

0 |

2 |

| Dizziness |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| Total of symptoms |

17 |

7 |

24 |

Table 4: Frequency of clinical adverse events in pregnant women under treatment.

Changes in function of liver, kidney and bone marrow of treated mothers were summarized in Table 5. Overall, no significant change in serum total bilirubine, urea, creatinine or hematologic elements was seen during the treatment.

| |

Organ function

parameters |

Before treatment

Mean ± SD (range) |

After treatment

Mean ± SD (range) |

p |

| Liver |

Total bilirubinemia (mmol/l) |

8.3 ± 3.85

(2.3 - 23) |

9 ± 3.42

(4 - 25) |

>0.05 |

| AST (IU/ml) |

23.3 ± 9.76

(11 - 54*) |

27.1 ± 12.85

(11 - 79*) |

0.001$ |

| ALT (IU/ml) |

22.7 ± 13.32

(9 - 75#) |

27.9 ± 19.01

(4.7 - 107 #) |

0.004$ |

| Kidney |

Urea (mmol/ml) |

3.1 ± 0.74

(2 - 5.2) |

3.1 ± 0.73

(1.5 - 5) |

>0.05 |

| Creatininemia (µmol/ml) |

55.7 ± 14.44

(35 - 97) |

58.2 ± 15

(36 - 131) |

>0.05 |

| Bone marrow |

Hemoglobine (g/l) |

117.7 ± 8.67

(91 - 139) |

118.5 ±10.34

(92 - 142) |

>0.05 |

| White cell (109/l) |

9.0 ± 2.1

(6.1 - 16.8) |

9.2 ± 2.1

(4.7 - 15.2) |

>0.05 |

| Platelet (109/l) |

206.7 ± 51.5

(96 - 374) |

208 ± 56.6

(100 - 381) |

>0.05 |

$Hepatic enzymes significant higher after treatment, but in the normal limits

*Abnormal level of AST, # abnormal level of ALT.

Table 5: Liver, kidney and bone marrow functions before and after treatment in studied pregnant women.

Although the absolute titers of AST and ALT were significantly increased after treatment in five pregnant women (Table 6) who were all under tenofovir with label code as “A”, mean titers of these hepatic enzymes were situated in the normal limits (27.1 ± 12.85 IU/ml and 27.9 ± 19.01 IU/ml, respectively)

| Cases |

At week 32 |

At week 36 |

At labor |

Week 4 postpartum |

| 1A |

48/57 |

74/78 |

43/57 |

65/97 |

| 49A |

43/45 |

43/60 |

51/63 |

79/107 |

| 63A |

43/50 |

38/83.1 |

32/46 |

15/17 |

| 83A |

52/20 |

40/45 |

35/28 |

39/31 |

| 92A |

54/75 |

46.7/71.3 |

52/42 |

37/29 |

Table 6: Details in changes of hepatic enzymes (AST/ALT) in 5 pregnant women.

In details, at baseline (week 32 of gestation), AST was slightly increased (43-54 IU/ml) in five cases, and ALT was slightly increased (45-75 IU/ml) in four cases. At labor, AST stayed increased (43-52 IU/ml) in three cases, and ALT stayed increased (42-63 IU/ml) in the same four cases. At week 4 postpartum, abnormal levels of AST and ALT were seen only in two cases, but the titers of AST and ALT were very slightly increased (65 and 97 IU/ml in one case and 79 and 107 IU/ml in the other), and no case of frank flare was seen. In 82 infants, we did not observe any abnormality which might be attributed to adverse events of the drugs in fetuses, newborns or infants.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated whether lamivudine versus tenofovir starting at the week 32 of gestation could comparatively reduce HBV perinatal transmission in infants borns to highly viremic mothers in order to find a rational and optiomal regimen for this situation in a low-income nation. Estimates of the risk for motherto- infant HBV transmission varied despite vaccination and were related mostly to maternal viremic load [6,9-16]. Previous studies suggested that maternal HBV DNA concentration >108 copies/mL (2.107 IU/mL) confers a ≥10% of risk for perinatal transmission despite immunoprophylaxis [6]. Moreover, recent data suggest that HBV transmission to infants could not be averted by vaccine prophylaxis alone, but could be prevented by concurrent nucleoside or nucleotide analogue therapies [6,17-28].

This is the first prospective study on efficacy of prenatal antiviral prophylaxis in Vietnam, and the third one on the world reporting the results of tenofovir treatment in late pregnancy for HBV perinatal transmission following the first report of Pan et al. from a retrospective study with a small sample size of 11 pregnant women in Mount Sinai Medical Center (USA) [33] and the second report of Chen et al. in China [34].

As mentioned in the results, HBV DNA levels at week 32 of gestation were very high in our study population, with a viral load >108 copies/mL in 71/82 (86.6%) pregnant women (>9.89 × 108 copies/mL in 15 cases, >6.4 × 108 copies/mL in 32 and >1-6.4 × 108 in 24 cases). Therefore, the high viral load at the Baseline in our study (5.09 × 108 ± 3.19 × 108 copies/mL) practically approached the level of 109 copies/mL in the study conducted by Xu et al. in China [17].

In our study, as usually seen in several longitudinal studies, the dropout rate was as high as 11.8% (11/93 mother-infant pairs). In detail, the dropout rate was 11/44 (25.0%) in lamivudine-treated mothers while it was nil (0/49) in tenofovir-treated mothers. Again, these figures approached those in placebo-treated group and lamivudine-treated study reported by Xu et al. in China (13% and 31%, respectively) [17]. High rate of droping out of mothers under lamivudine had taken place during the first half of the study. The most common causes included misunderstood information when consulting the internet by patients and their family, as well as bad counseling from some of their attendant doctors, who were not members of the research team. In fact, these patients and physicians wrongly believed a short course of lamivudine in subject’s naïve to antivirals in our selective pregnant women might as such easily lead to early and frequent viral resistance to the drug as it was confirmed in patients with chronic hepatitis B under long course of treatment. During the second of the study, better counseling with clearer explanation to pregnant women and their family was since then reinforced and no more case of dropout occurred. We did not realize the intention-to-treat analysis in our study, because of a very large disproportion of dropout rates in two study subgroups (25.0% in mothers treated by lamivudine in contrast to 0/% in mothers treated by tenofovir), possibly leading a very largely skew interpretation when comparing efficacy of the two drugs.

In our study, HBsAg positivity rate in umbilical cordon blood at birth, was 21/82 (25.6%); that was comparable to 20% and 24% in children born to mothers under telbivudine and no treatment, respectively, reported by Zhang et al. in China [30]. There was a higher tendency of HBsAg positivity in infants born to mothers under tenofovir than those born to mothers under lamivudine (16/49 (32.7%) compared to 5/33 (15.2%), however this tendency was not statistically significant (p=0.075). HBV DNA was detectable in 8.5% (8.2% in children borned to mothers treated by Tenofovir versus 9.1% in those borned to mothers under Lamivudine, p>0.05); it’s pratically similar to 6.15% among 62 children born to mothers under tenofovir in Taiwan reported very recently by Chen et al. [34]. The overall rate of HBV perinatal transmission, defined as serum HBsAg positivity at 52 weeks, was very low, only 1.2% (1/82) in this study. This rate was comparable to 1.52% in the study of Chen et al. in Taiwan [34], but clearly higher than 0% at 6-month-old in 309 children born to mothers under either telbivudine (257 infants) or lamivudine (52 infants) in study of Zhang et al. in China [30]. We also identified one case of HBV horizontal infection in this study. This infant was HBsAg negative and HBV DNA undetectable at birth and at 6 months of age, but unfortunately anti-HBsAg antibody stayed negative at 6 months, and his father and his elder brother were retrospectively revealed HBsAg positive. Therefore, he was presumably horizontally infected some time after 6 months of age due to failure of protective antibody production and living in familial environment at very high risk for HBV infection similarly to the case reported by Chen et al. in Taiwan in 2015 [34].

Our results are consistent with other studies conducted in Asia and worldwide [17-29]. In a prospective study in China, a total of 151 HBsAg positive women with HBV DNA levels at approximately 107 copies/mL, randomly located to receive HBIg (from 28 weeks of gestation until labor), lamivudine (from 28 weeks of gestation to 4 weeks after birth) or no treatment (control group), Li et al. found a reduction of serum HBV DNA by a mean of 2 log10 in 2 active treatment groups. HBV transmission was reduced by 50% in both the HBIg group (16.1%) and the lamivudine group (16.3%) compared to 32.7% in untreated control group [29]. In another randomized double blind placebo-controlled study also in China, Xu et al. showed that lamivudine given from week 32 of pregnancy to mothers with HBV DNA concentration of 109 copies/mL (1,000 mEq/mL) at baseline resulted in a reduction by a mean of 2 log10 copies/mL in the active treatment group. It also showed that at 52 weeks of age, 18% of infants born to 56 treated mothers were HBsAg positive, compared to 39% of infants in 26 placebo recipients [17]. In another randomized,double blind, placebo-controlled study using telbivudine in 190 HBsAg/HBeAg positive mothers with HBV DNA concentration >1.0 × 107 copies/mL at week 20-32 of gestation, Han et al. noted that HBV DNA level decreased from 8.19 log10 copies/mL to 2.35 log10 copies/mL compared to 7.96 and 7.8 log10 copies/ mL in untreated mothers with HBV HBV DNA undetectable in serum of 30% treated mothers. At 28 weeks of age, on intentionto- treat analysis, HBsAg positive rate was 2.1% in infants born to telbuvidine-treated mothers versus 13% in infants of untreated mothers. On per-protocol analysis, however, HBsAg positive rate was 0% in infants born to telbuvidine-treated mothers versus 8% in infants of untreated mothers (p=0.002) [20]. Recently, Zhang et al. reported very good results of a very large prospective openlabel study enrolling 700 HBsAg/HBeAg positive pregnant women with HBV DNA >6 log10 copies/mL, receiving either telbivudine or lamivudine or no treatment as control group at 28 weeks of gestation in a tertiary hospital in Beijing (China) between January 2009 and March 2011. At week 52, the rate of HBsAg positive was 2.2% of infants in treated group versus 7.6% in no treatment group (p=0.001) in the intention-to-treat analysis; this rate became 0% versus 2.84% (respectively, p=0.002) in the on-treatment analysis. The treatment was well tolarated and no safety concerns identified [30]. In a meta-analysis looking at the efficacy of lamivudine in interrupting mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus from 15 randomized controlled trials, enrolling 1,693 chronic HBV carrier pregnant womens, Han et al. reported an efficacy of around overall RR of 0.43 (95% CI, 0.25-0.76), indicated by HBsAg or HBD DNA of infants at 6-12 months after birth. The authors also noted that the incidence of adverse effects of lamivudine was not higher in treated women and their offspring than in controls (p>0.05), and that the treatment might be only efficient if maternal viral load is reduced to <106 copies/mL under lamivudine [19].

The data on the efficacy and safety of tenofovir in late pregnancy to prevent the vertical transmission of HBV to infants born to highly viremic mothers are very limited so far in medical literature worldwide. As far as we know, the first and unique report of Pan et al. from a retrospective study with a small sample size of 11 pregnant women in Mount Sinai Medical Center (USA) showed a very promising results, with high safety and a good reduction of HBV DNA load from 8.87 ± 0.45 log10 copies/mL at baseline (28-32 weeks of gestation) to 5.25 ± 1.79 log10 copies/mL at delivery, and none of 11 infants were HBsAg positive at 28-36 weeks after birth [33]. In a very recent open-labeled control study with a lagrge population of 118 pregnant women (62 in tenofovir-treated group and 56 in non-treated control group), Chen et al. in Taiwan reported a very good results. At delivery, maternal HBV DNA in the group under tenofovir reduced drastically from 8.18 ± 0.47 log10 IU/ml to 4.29 ± 0.93 log10 IU/ml versus 8.22 ± 0.39 and 8.10 ± 0.56 log10 IU/ml in the control group, respectively (p<0.0001). Children born to mothers under tenofovir had a lower rate of HBV DNA positivity at birth (6.15% vs. 31.48%, p=0.0003) and lower HBsAg positivity at 6-month-old (1.54% vs. 10.71%, p=0.0481) [34].

In obligation of ethical concerns in human studies as well as scarcity of untreated comparative cases for the period of study time, we could not designed the untreated control group in order to clearly deliniate the part of efficacy of antiviral prophylaxis from the role acting by vaccination. Therefore, the very low rate of perinatal transmission obtained

in our study (1.2%) could not easily explained. Nevertheless, this might partly be the results of not only good practice of HBV vaccination in the mass where this cohort comes from, but also of high sensibility (with a mean HBV DNA reduction of 5.08 × 108 ± 3.17 × 108 after 8 weeks of treatment) of HBV virus naïve to the drugs used. As a result of inclusion criteria in our study, all of our participants had never been exposed to any antiviral against hepatitis B virus. As a consequence, the part of our study carried out in AlphaBio Labo in Marseille (Pr Halfon) did not detect any instance of resistance to lamivudine or to tenofovir amongst 29 blood samples from 21 mother whose offspring was HBsAg positive at birth, and 8 mothers whose HBV DNA reduction at labour was modest (<2 log10). Therefore, the absence of viral resistance to lamivudine and tenofovir might be another explanation for the very low rate of perinatal transmission of HBV in the present study. This notion of viral resistance to antivirals in a study population with exclusion of subjects who were preexposed to antivirals against hepatitis B virus was not mentioned in any other study as far as we know.

After 8 weeks of treatment using either tenofovir or lamivudine, we noted a remarkable reduction of HBV DNA levels in treated mothers. The mean maternal serum HBV DNA of 5.09 × 108 ± 3.19 × 108 at week 32 of gestation was reduced to 1.13 × 106 ± 3.91 × 106) at the moment of labor (p<0.001). The mean HBV DNA reduction was by then 5.08 × 108 ± 3.17 × 108, without significant difference between tenofovir and lamivudine-treated groups. The mean maternal serum HBV DNA loads in two subgroups treated by tenofovir and lamivudine depicted in Table 1 (4.98 ± 3.42.108 and 4.86 ± 3.68.108, respectively) was slightly lower than the above-mentioned total load (5.09 × 108 ± 3.19 × 108) as a result of wider standard deviations in the former figures than in the latter. When strastifying the viral load reduction of HBV DNA in log10, we found that HBV DNA reduction in the tenofovir-treated mothers was significantly stronger than that in the lamivudine-treated mothers. In mothers under lamivudine, HBV DNA reduction aggregated in 1-3 log10 (75.8%), while it was found to aggregate in 3-4 log10 (81.7%) in mothers under tenofovir. As the result, the HBV DNA reduction in 1-2 log10 was significantly stronger in mothers under lamivudine than in those under tenofovir, 36.4% compared to 4.1% (p<0.01), while the reduction in 4 log10 was far stronger in mothers under tenofovir than in those under lamivudine, 51.1% compared to 15.2% (p<0.001). Interestingly, we also noted two cases (6.6%) with undetectable HBV DNA amongst 33 mothers under lamivudine.

It is easy to understand that none of the eight infants born to mothers with a strong viral reduction of 5-8 log10 was HBsAg positive or HBV DNA detectable at birth. However, it is surprising and difficult to explain why none of the 14 infants born to mothers in whom HBV DNA reduction was slight (1-2 log10 copies/mL) was HBV DNA detectable at birth, while amongst the 60 offsprings of treated mothers whose viral load reduction was rather strong (3-4 log10 copies/mL), seven were positive HBsAg and detectable HBV DNA at birth, then one remained positive at 6 and 12 months (the unique case of perinatal transmission in the study).

Furthermore, although HBV DNA levels at the time of delivery remained 106 copies/mL in 12/82 treated mothers (14.6%) (10 under lamivudine and 2 under tenofovir), all offsprings of these mothers with modest viral load reduction were intact at week 52, while in the unique HBV perinatal infection case, the baseline maternal viral load was >6.4 × 108 copies/mL reducing to 5.82 × 105 copies/mL at labor under tenofovir treatment. We speculate that this infant might be already infected by HBV before treatment initiation, either via placenta or even by the presence of hepatitis B virus in oocytes and embryos, as reported by Nie et al. [35]. Future studies will be needed to prove this hypothesis.

As expected, in our study using reverse hybridization based line probe assay as previously described [36], no case of viral resistance to tenofovir and lamivudine was seen in 29 treated mothers. Resistance to lamivudine in chronic hepatitis B patients with long-term treatment is well known and frequent [37-39]. However, HBV resistance to lamivudine for a short course of treatment in pregnant women had never been reported as far as we know. So far, HBV resistance to tenofovir has not been identified in medical literature worldwide even after five years of treatment in chronic hepatitis B patients [34,40-42]. In our study, the treatment course was very short (8 weeks before delivery) and all pregnant women are naïve to these antivirals, therefore, secondary resistance to the drug had no chance to happen yet. On the other hand, primary viral resistance to the drug (before infecting the study subjects) is naturally rare in Vietnam, where lamivudine has been available for less than 20 years and the indication of this drug is not frequent.

In this first study using antiviral drugs in pregnant women in Vietnam, we initiated the treatment only at week 32 of gestation due to lack of experience in the field but also due to ethical concerns. However, shouldering on large experience worldwide on the safety [6,17,19,23-31,34] as well as viral load threshold <6 log10 copies/mL to limit perinatal HVB transmission [4,6,19], this treatment should be initiate sooner in the gestational period, when maternal viral load stays far lower than 7-8 log10 copies/ mL. In our own opinion, antiviral could be administered between week 20 and 24 of gestation when the process of organogenesis in the fetus has been well completed.

No major safety concerns was noted either in mothers during treatment in late pregnancy, in their fetuses at birth, or in infants for 52 weeks of follow-up in our study. The safety of lamividine and telbivudine during late pregnacy has been reported in several studies [17,19,23-30]. For tenofovir, a recent antiviral drug classified as Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pregnancy risk category B, data collected in human exposure from 606 pregnant women in the first trimester and 336 in the second trimester showed an associated rate of birth defects ranging from 1.5% (second-trimester use) to 2.3% (first-trimester use) [26], which were to the same as the background rate in general population without exposure to these drugs [6,26,29,31,34]. Tenofovir has very recently been recommended by FDA for use in HBsAg positive pregnant women who suffer from serious liver underlying diseases (active hepatitis, hepatic cirrhosis), or who expect to breastfeed their babies or to continue antiviral therapy after delivery [6,26,31,43,44]. As the result, so far, few clinical trials using tenofovir for preventing HBV perinatal transmission in highly viremic mothers had been carried out. Our study is, therefore, one of the first studies using tenofovir in pregnant women to prevent HBV perinatal transmission in highly viremic mothers with results of high efficacy and good safety reported. However, given the double cost of tenofovir in comparison to lamivudine and more frequent adverse events in groups treated by tenofovir than in lamivudine treated group in this study, from the point of view of cost-effectiveness and public health in a lowincome country with high endemicity of HBV, we suggest that lamivudine should be considered as the drug of choice for this specific purpose.

Conclusion

Through this first study dealing with HBV perinatal prevention using antiviral prophylactic therapy in late pregnancy in very highly viremic mothers in Vietnam, we found that this strategy might be applicable in daily practice without complication or vicissitude. Our results showed that lamivudine and tenofovir exhibited a high efficacy in preventing mother-to-child perinatal transmission of HBV and a good safety. Therefore, in our vision, a priority for the use of lamivudine in short course with the specific purpose of preventing perinatal transmission in highly viremic mothers seems rational in a low-income country with a high endemicity of HBV.

Acknowledgements

The authors deeply thank

1. Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) of Vietnam and French Embassy in Hanoi for approving, sponsoring and following-up this project

2. Ministry of Health (MOH) of Vietnam for approving and encouraging the project proposal

3. Hanoi Medical University (HMU) for ethical approvement and management of the project

4. Direction Board of the 4 participating institutions for their administrative and professional cooperation

5. AlphaBio Labo of European Hospital in Marseille for their close collaboration during the study

6. All collaborating investigators who recruited patients in this project and Professor Hoang Minh Hang for her consistent contribution in statistical aspects of the project.

Funding Contribution

1. Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) of Vietnam.

2. French Embassy in Hanoi.

3. AlphaBio Labo of European Hospital in Marseille.

6455

References

- Elizabeth W, Hwang, Cheung R (2011) Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection. North Am J Med Sci 4: 8.

- Mahoney FJ (1999) Update on diagnosis, management, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 12: 351-366.

- Sung JL1 (1990) Hepatitis B virus eradication strategy for Asia. The Asian Regional Study Group. Vaccine 8 Suppl: S95-99.

- WHO (2015) Chapter 10.2. Prevention of mother-to-child HBV transmission using antiviral therapy. In: Prevention, care and treatment of persons with chronic Hepatitis B infection March 2015.

- Nguyen VT, McLaws ML, Dore GJ (2007) Highly endemic hepatitis B infection in rural Vietnam. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 22: 2093-2100.

- Dusheiko G (2012) Interruption of mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis B: time to include selective antiviral prophylaxis? Lancet 379: 2019-2021.

- Chen DS (2010) Toward elimination and eradication of hepatitis B. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 25: 19-25.

- Ni YH, Chen DS (2010) Hepatitis B vaccination in children: the Taiwan experience. Pathol Biol (Paris) 58: 296-300.

- (1993) Hepatitis in pregnancy. ACOG Technical Bulletin Number 174--November 1992. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 42: 189-198.

- Jonas MM (2009) Hepatitis B and pregnancy: an underestimated issue. Liver Int 29 Suppl 1: 133-139.

- Umar M, Hamama-Tul-Bushra, Umar S, Khan HA (2013) HBV perinatal transmission. Int J Hepatol 2013: 875791.

- Hsu HY, Chang MH, Hsieh KH, Lee CY, Lin HH, et al. (1992) Cellular immune response to HBcAg in mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus. Hepatology 15: 770-776.

- Vranckx R, Alisjahbana A, Meheus A (1999) Hepatitis B virus vaccination and antenatal transmission of HBV markers to neonates. J Viral Hepat 6: 135-139.

- Wiseman E, Fraser MA, Holden S, Glass A, Kidson BL, et al. (2009) Perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus: an Australian experience. Med J Aust 190: 489-492.

- Xiao XM, Li AZ, Chen X, Zhu YK, Miao J (2007) Prevention of vertical hepatitis B transmission by hepatitis B immunoglobulin in the third trimester of pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 96: 167-170.

- Xu Q, Xiao L, Lu XB, Zhang YX, Cai X (2006) A randomized controlled clinical trial: interruption of intrauterine transmission of hepatitis B virus infection with HBIG. World J Gastroenterol 12: 3434-3437.

- Xu WM, Cui YT, Wang L, Yang H, Liang ZQ, et al. (2009) Lamivudine in late pregnancy to prevent perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus infection: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Viral Hepat 16: 94-103.

- Deng M, Zhou X, Gao S, Yang SG, Wang B, et al. (2012) The effects of telbivudine in late pregnancy to prevent intrauterine transmission of the hepatitis B virus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Virol J 9: 185.

- Han L, Zhang HW, Xie JX, Zhang Q, Wang HY, et al. (2011) A meta-analysis of lamivudine for interruption of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus. World J Gastroenterol 17: 4321-4333.

- Han GR, Cao MK, Zhao W, Jiang HX, Wang CM, et al. (2011) A prospective and open-label study for the efficacy and safety of telbivudine in pregnancy for the prevention of perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol 55: 1215-1221.

- Pan CQ, Han GR, Jiang HX, Zhao W, Cao MK, et al. (2012) Telbivudine prevents vertical transmission from HBeAg-positive women with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 10: 520-526.

- Shi Z, Li X, Ma L, Yang Y (2010) Hepatitis B immunoglobulin injection in pregnancy to interrupt hepatitis B virus mother-to-child transmission-a meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 14: e622-634.

- Shi Z, Yang Y, Ma L, Li X, Schreiber A (2010) Lamivudine in late pregnancy to interrupt in utero transmission of hepatitis B virus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 116: 147-159.

- Su GG, Pan KH, Zhao NF, Fang SH, Yang DH, et al. (2004) Efficacy and safety of lamivudine treatment for chronic hepatitis B in pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol 10: 910-912.

- Tran TT, Keeffe EB (2008) Management of pregnant hepatitis B patient. Current Hepatitis Reports 7: 12-17.

- Tran TT (2009) Management of hepatitis B in pregnancy: weighing the options. Cleve Clin J Med 76 Suppl 3: S25-29.

- van Nunen AB, de Man RA, Heijtink RA, Niesters HG, Schalm SW (2000) Lamivudine in the last 4 weeks of pregnancy to prevent perinatal transmission in highly viremic chronic hepatitis B patients. J Hepatol 32: 1040-1041.

- van Zonneveld M, van Nunen AB, Niesters HG, de Man RA, Schalm SW, et al. (2003) Lamivudine treatment during pregnancy to prevent perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus infection. J Viral Hepat 10: 294-297.

- Li XM, Yang YB, Hou HY, Shi ZJ, Shen HM, et al. (2003) Interruption of HBV intrauterine transmission: a clinical study. World J Gastroenterol 9: 1501-1503.

- Zhang H, Pan CQ, Pang Q, Tian R, Yan M, et al. (2014) Telbivudine or lamivudine use in late pregnancy safely reduces perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus in real-life practice Hepatology 60: 468–476.

- Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry Steering Committee (2008) Antiretrovital pregnancy reistery international interim report for 1 January 1089 through 31 July 2008. Wilmington, NC: Registry Coordinating Center, 2008. Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registery Web site.

- Deveci Ö, Yula E, Özer TT, Tekin A, Kurkut B, et al. (2011). Investigation of intrauterine transmission of Hepatitis B Virus to children from HBsAg-positive pregnant women. Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 1 : 14-16.

- Pan C, Mi LJ, Bunchorntavakul Ch, Karsdon J, Huang W, et al. (2012) Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate for Prevention of Vertical Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus Infection by Highly Viremic Pregnant Women: A Case Series. Dig Dis Sci 57: 2423-2429.

- FDAAA 801 and NIH draft reporting policy for NIH funded trials (2011) Tenofovir in late pregnancy to prevent vertical transmission of hepatitis B virus: A multicenter 17 prospective randomized open-label study. NCT01488526, New Discovery LLC & Gilead Sciences.

- VanGeyt C, DeGendt S, Rombaut A, Wyseur A, Maertens G, et al. (1998). A line probe assay for hepatitis B virus genotypes, p. 139–145. In RF Schinazi, JP Sommadossi and H Thomas (edn), Therapies of viral hepatitis. International Medical Press, London, United Kingdom.

- Lai CL, Dienstag J, Schiff E, Leung NW, Atkins M, et al. (2003) Prevalence and clinical correlates of YMDD variants during lamivudine therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Infect Dis 36: 687-696.

- Hann HW, Gregory VL, Dixon JS, Barker KF (2008) A review of the one-year incidence of resistance to lamivudine in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B : Lamivudine resistance. Hepatol Int 2: 440-456.

- Wani HU, Al Kaabi S, Sharma M, Singh R, John A, et al. (2014) High dose of Lamivudine and resistance in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepat Res Treat 2014: 615621.

- Corsa AC, Liu Y, Flaherty JF, Mitchell B, Fung SK, et al. (2014) No resistance to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate through 96 weeks of treatment in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 12: 2106-2112.

- O’Brien P, Miller C (2013) Viread® for hepatitis B maintains antiviral suppression with no development of resistance through four years of treatment. Gilead Sciences, Inc. 2009-2013.

- Roehr B (2011) No hepatitis B virus resistance to tenofovir seen out to 5 years. File under AASLD Nov 201, HBV.

- Wang L, Kourtis AP, Ellington S, Legardy-Williams J, Bulterys M (2013) Safety of tenofovir during pregnancy for the mother and fetus: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis 57: 1773-1781.

- (2014) Oxford University Press on behalf of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2013. Breastfeeding While Taking Lamivudine or Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate: A Review of the Evidence Clin Infect Dis :ciu798v2-ciu798.

- CM Kukka (2014) Tenofovir or Telbivudine Recommended for Pregnant Women with High Viral Loads. HBV Advocate Friday, September , 2014