Keywords

Human strondyloidiasis; StrongyloideS stercoralis; Pathophysiology of strongyloidiasis; Laboratory diagnosis and prophylaxis of strongyloidiasis

Introduction

Strongyloidiasis is an infectious parasitic disease caused by the intestinal nematode StrongyloideS stercoralis. This infection is prevalent worldwide except in the Antarctica and with predominance in the warm and humid climates of tropical and sub-tropical regions of the world. Human infection with S stercoralis was first discovered in French soldiers returning from Indochina borders and is called as cochin-china diarrhoea [1].

It has been noted that dogs, cats and other mammals may act as reservoirs of S stercoralis. Strongyloides fulleborni, S myopotami and S procynosis are the only other species of Strongyloides among the 52 identified ones that causes infections usually in chimpanzees and baboon and other animals and may accidentally infect humans (zoonotic Strongyloidiasis) [2,3].The exact prevalence rates of strongyloidiasis is not known by it is estimated that about 100 million people might be affected throughout the world [4]. It has been observed that strongyloidiasis is more commonly seen among the rural population and in people living in poverty. The predisposing factors for infection with S. stercoralis include walking bare footed in soil contaminated with human faeces and sewage water.

Life cycle of S stercoralis

S. stercoralis is a typical parasite which not only has the ability to continue living freely in the environment (soil and water), but also can cause mild to severe and life threatening human infections. The free living cycle of the Strongyloides starts with the deposition of rhabditiform larvae in the soil, which instead of transforming in to the infective filariform larva, develops in to the adult male and female worm, undergo fertilization and produce rhabditiform larvae. The rhabditiform larvae instead of continuing the free living cycle may in some cases directly develop in to the infective filariform larvae and penetrate human skin thus initiating infection and the infective/parasitic life cycle [5]. Filariform larvae that penetrate the skin with the help of histolytic protease enzyme wanders through the sub cutaneous connective tissues and reaches the intestines or in some cases the filariform larvae penetrate the skin and directly enter the blood through lymphatic system and after reaching the lungs may either be coughed out or be swallowed in to the stomach and move towards the intestines. After reaching the intestines the filariform larvae attach themselves to the intestinal epithelial cells and also get embedded in to the intestinal folds, develop in to the adult forms and females undergo self-fertilization (parthenogenesis) to release eggs in to the lumen of the intestine which immediately hatch out rhabditiform larvae. The rhabditiform larvae thus released are passed out through faeces to continue free-living cycle in the environment or may immediately transform in to a filariform larva and penetrate intestinal mucosa/perinea skin resulting in internal auto infection. Some of the rhabditiform larvae move towards the perianal regions and develop in to filariform larva and may penetrate the skin to cause external autoinfection [6,7].

Predisposing factors for infection with S stercoralis

Although the exact incubation time from the skin penetration to the initial symptoms is not clear, it is believed that it may take around one month for the presence of larvae in the faeces.

The predisposing factors for StrongyloideS stercoralis infection are corticosteroid therapy [8,9]. other immunosuppressive treatment that include chronic antibiotic therapy and treatment with tumour necrosis factor (TNF) modulators. Human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV), solid organ/haematological malignancies, organ transplantation, malnutrition, hypogammaglobulinaemia, chronic renal disease, collagen/vascular diseases, metabolic disorders, alcoholism and old age are other factors which may predispose to strongyloidiasis [10-16].

Epidemiology of human strongyloidiasis

Human strongyloidiasis is considered as a neglected tropical disease and is under diagnosed parasitic infection [17-19]. There are only few studies available in literature reporting the epidemiology of strongyloidiasis throughout the world. It has been observed that the prevalence of strongyloidiasis ranges between 10 and 40% in tropical and subtropical regions of the world [20]. A whopping 40% prevalence was reported from African region, south-east Asian regions, Middle East, parts of Brazil, Spain and Australia [21-24]. A prevalence rate of 8.7% was noted in the Peruvian Amazon region [25]. Prevalence was more frequent among children attributed to their playing habitats and hygiene habits [26]. S stercoralis infection is rare in America excepting some parts (Appalachia, Kentucky, West Virginia, Puerto Rico and Tennessee) which revealed a prevalence rate of 4% [27]. A study from china showed an increased prevalence during previous decade and overall cases reported [28]. A study from Malaysia, which reviewed the data of 12 years revealed a prevalence rate of 0.08%. This study also has observed that among the infected population 92% of them had one or the other comorbidities [29]. A study reported from Cambodia which included 458 schools going children and screened for the presence of S stercoralis, showed a prevalence rate of 24.4% [30]. Another recent study from rural Cambodia has revealed a high incidence of human strongyloidiasis (44.7%) [31]. An isolated single case of S stercoralis infection in an 8 year old school going white girl was reported recently from north-eastern America (Pennsylvania) [32]. Epidemiological survey study of human strongyloidiasis in Japan showed that the prevalence among community (18.7%) was found to be higher as compared to the hospital diagnosed cases (13.6%) [33]. Two studies from Peru have revealed that the prevalence of strongyloidiasis was noted to be higher (22%) when multiple diagnostic tests were performed as compared to the use of only serological based methods (8.7%) [25,34]. Although epidemiological studies from India are hardly available, there are several isolated case studies which undermine the actual prevalence of human strongyloidiasis in India and many other tropical and subtropical countries [35-43].

Pathophysiology of strongyloidiasis

In most of people the infection may remain symptomless but some patients might show clinical symptoms that may include abdominal pain, nausea, loss of appetite, alternate bouts of diarrhoea and constipation, blood in the stool (occult blood), epigastric pain, post prandial fullness of stomach, bloating and some complaining heartburns. Presence of parasites in lungs may precipitate dry cough and recurrent sore throat. Movement of the parasite under the skin called as larva currens causes erythematous raised skin rashes (utricaria, serpiginous maculopapular rash) usually involving the legs, thighs, perineal regions and the buttocks [44]. Auto infection may lead to chronic, persistent infection and among immunocompromised individuals S stercoralis may cause hyper infection syndrome and disseminated strongyloidiasis [45-48].

It has also been noted that patients suffering from chronic strongyloidiasis may present with arthritis, signs and symptoms related to chronic malabsorption, duodenal obstruction, nephritic syndrome, symptoms of asthma and cardiac arrhythmias. Mild to moderate eosinophilia was observed to be the most common laboratory haematological finding among the infected patients. Hyper infection syndrome can be diagnosed by clinical symptoms that include vomiting, ileus, bowel oedema, intestinal ulceration, obstruction, appendicitis and haemorrhage, peritonitis, secondary bacterial sepsis and nephrotic syndrome [49-51]. Respiratory tract symptoms indicating hyper infection could be presenting as wheezing, dyspnoea, Pneumonitis, haemoptysis, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and respiratory failure [52-57]. Pulmonary haemorrhage secondary to disseminated S stercoralis infection was noted in a patient with systemic lupus erythematous, signifying the importance of co-morbidities in the management of human strongyloidiasis [58]. Larval migration in the brain may show clinical presentation that includes aseptic/bacterial meningitis. In children with malnutrition infection with S stercoralis may present as chronic and persistent diarrhoea, cachexia, anorexia and failure to thrive. It is important to note that initiation of immunosuppressive therapy in clinically asymptomatic carriers may result in hyper infection and serious consequences (severe morbidity and mortality) [39]. A recent report on the activities of CD4+ T cell subsets including the Th1, Th2 and Th17 during chronic infection with S stercoralis has revealed that there was an increase in the frequency of non-functional and dual functional Th2 cells against the specific S stercoralis antigen. This study has also confirmed that up on initiation of treatment there was decreased frequency of Th2 cells. This study might be instrumental in advancement of further immunological research studies in Strongyloides infection and a hope to develop a vaccine in future [59,60].

A recent study has highlighted the importance of screening for chronic Strongyloides infection as it could be responsible for complications arising from other associated infections. This study reported a paediatric patient from Dominican Republic suffering from recurrent pruritic rash, eosinophilia that presented with acute onset bacterial meningitis and was later investigated and observed to be suffering from chronic strongyloidiasis. This case should be considered as a best example to explain the fact that chronic infection with S stercoralis could be a predisposing factor for the development of hyperinfection syndrome under immunocompromised conditions/glucocorticoid therapy/ immunosuppressive treatment [61].

Isolated reports and the significance of underlying conditions in precipitating human strongyloidiasis are present in the literature. Infection with human strongyloidiasis among patients suffering from ulcerative colitis, disseminated strongyloidiasis in a diabetic patient, strongyloidiasis associated with malignant pleural effusion, respiratory hyperinfection in a patient suffering from renal failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) attributed to infection with S stercoralis infection in a patient with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and disseminated strongyloidiasis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients are some of the clinical presentations of human strongyloidiasis in supposedly endemic countries which should be considered as a serious concern that requires further research and greater understanding of the clinical course of Strongyloides infection [62-68].

Laboratory diagnosis of Strongyloidiasis

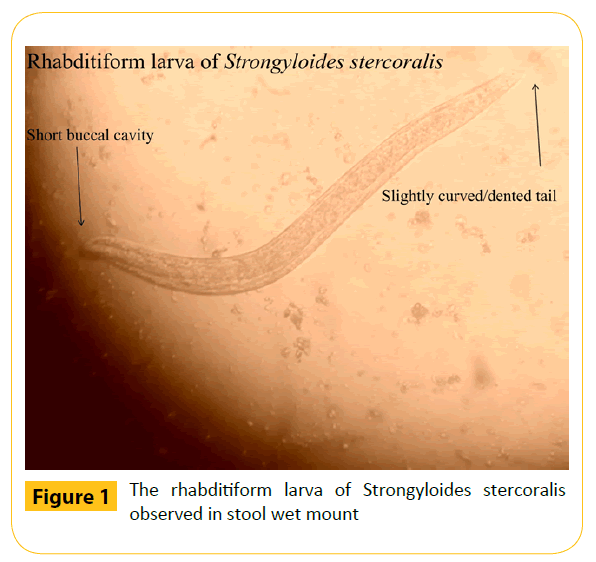

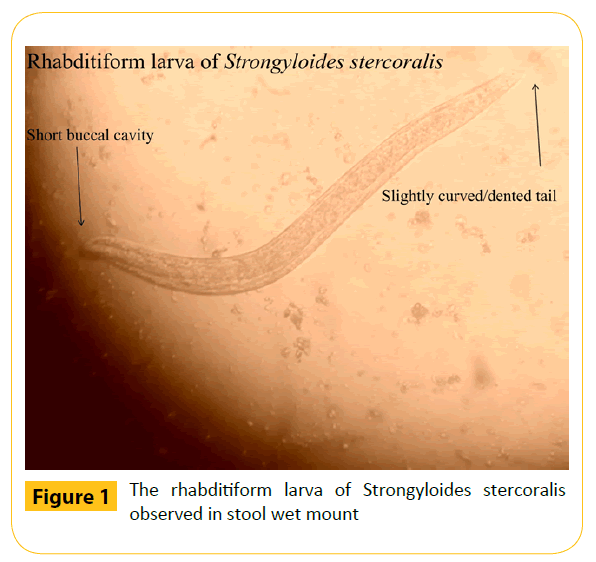

Laboratory diagnosis of strongyloidiasis involves demonstration of larvae in stool using the wet mount method, the most common microscopic method (Figure 1). Sensitivity of a single direct faecal microscopic examination was found to be less than 30% and that there is 70% probability if three faecal specimens are screened. The chances of finding larvae increases only after collecting and observing more than seven samples from each suspected patient; applying stool concentration techniques together with other advanced laboratory techniques [69,70]. Microscopy of other specimens including sputum, vomitus, duodenal aspirates, cerebrospinal fluid, ascetic fluid and others may also be beneficial in cases of hyper infection and disseminated strongyloidiasis. Histological examination of duodenal aspirates and duodenal and jejuna biopsy samples for diagnosing strongyloidiasis were also found to be promising [71-74]. Other methods for diagnosing infection with S stercoralis include the detection of specific IgG antibodies using enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), radioallergosorbent test for detection of specific IgE antibodies, indirect immunofluorescence test, complement fixation test, gelatine particle agglutination test and western blot assay [75,76]. Skin test utilising the S stercoralis larval extracts has also been tried [18]. Luciferase immunoprecipitation system (LIPS) method, which was recently described, was proven to be better than ELISA for the diagnosis of strongyloidiasis [77]. Molecular diagnostic techniques using multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR), real-time PCR are available for more sensitive and specific diagnosis of strongyloidiasis [78,79]. A recent research study from Brazil has evaluated the utility of ELISA for the detection of serum IgG and salivary IgA in the diagnosis of Strongyloidiasis. This study has also compared ELISA with stool examination and found that serum IgG ELISA showed high specificity and sensitivity as compared to salivary IgA and that there was possibilities of around 26% cross reactivity with other parasitic infection [80]. Other methods of laboratory diagnosis of human strongyloidiasis include immunofluorescence antibody test (IFAT) and western blot (WB) [81,82]. A recent study has observed that it is very important to accurately diagnose strongyloidiasis especially among immunocompromised patients and that stool microscopic methods should always be complimented with advanced immunological and molecular methods to improve the efficacy of laboratory diagnosis of human strongyloidiasis [83]. Detection of parasite-specific micro RNA’s in the stool specimens and the possibility of circulatory micro RNA’s in the blood could pave a new way for the development of advanced means of diagnosis in human strongyloidiasis [84].

Figure 1: The rhabditiform larva of Strongyloides stercoralis observed in stool wet mount

Prophylaxis against Strongyloidiasis

Treatment in case of acute or chronic infection with S stercoralis is done using albendazole and mebendazole. Although thiabendazole is also effective, it may not be preferred due to the adverse side effects. Currently ivermectin is considered as a drug of choice for the treatment of strongyloidiasis. World health organization (WHO) recommends use of either albendazole or ivermectin at a dose of 400 mg daily for three days and single dose of 200 μg/kg bodyweight respectively [85,86]. A previous study has observed that treatment of strongyloidiasis among people co-infected with human T-cell leukaemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is difficult which could be attributed to elevated expression of gamma-interferon (IFN-γ) and tissue growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1). This study has also noted that increase in the IgG4 subsets as compared to IgE antibodies could function as blocking antibodies restricting the IgE mediated immune response [87].

A systematic study of case reports of strongyloidiasis presenting as hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated strongyloidiasis has observed that people in endemic regions should be thoroughly screened, high risk patients must be identified and noted that ivermectin is the gold standard for the treatment of severe strongyloidiasis [88].

Conclusion

From the available literature it is evident that the stool microscopy has less sensitivity in detecting larvae of S stercoralis and should not be considered as a routine screening method for the diagnosis of Strongyloidiasis. If microscopy is the only method available, at least three stool specimens must be collected from the suspected patients and a wet mount can be observed only after performing any one larval concentration methods. Studies thus far have also demonstrated the utility of serological and molecular methods in the specific diagnosis of strongyloidiasis. Due to the low sensitivity of stool microscopy, there is an urgent need to incorporate an ELISA based technique to assist the laboratory diagnosis of strongyloidiasis. Clinicians should be aware of the fact that S stercoralis infection among the immunocompromised individuals and in patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy are at increased risk of developing hyper infection syndrome, disseminated and fatal form of strongyloidiasis resulting in mortality. Children are at increased risk of contracting strongyloidiasis due to their habits of playing in environments (soil and water) contaminated with larvae especially in the developing and third world countries. Improved sewage disposal techniques, better sanitation and practicing hygienic habits may reduce the risk of infection. From the available literature it becomes evident that the clinical course of human strongyloidiasis may also be influenced by co-morbidities and that there is an emergent need for studies on the better understanding of epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation, immunology and improved approaches towards the diagnosis and therapy of S stercoralis infection.

8004

References

- Normand A (1983) Sur la maladieditediar-rh.e de Cochinchine. C R AcadSci (Paris) 83: 316

- Ashford RW, Barnish GB (1989) Strongyloidesfuelleborni and similar parasites in animals and man. In: Grove DI, editor. Strongyloidiasis: a major roundworm infection of man. London: Taylor & Francis 271-286

- Goncalves AL, Machado GA, Goncalves-Pires MR, Ferreira-Junior A, Silva DA, et al. (2007) Evaluation of strongyloidiasis in kennel dogs and keepers by parasitological and serological assays. Vet Parasitol 147: 132-139.

- Bethony J, Brooker S, Albonico M, Geiger SM, Loukas A, et al. (2006) Soil-transmitted helminth infections: ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm. Lancet 367: 1521-1532.

- Grove DI (1989) Historical introduction. In: Grove DI, editor. Strongyloidiasis: A Major Roundworm Infection of Man. Philadelphia (Pennsylvania): Taylor & Francis.

- Mansfield LS, Niamatali S, Bhopale V, Volk S, Smith G, et al. (1996) Strongyloidesstercoralis: maintenance of exceedingly chronic infections. Am J Trop Med Hyg 55: 617-624.

- Viney ME, Lok JB (2007) Strongyloides spp. WormBook, ed. The C. elegans Research Community, WormBook.

- Fardet L, Genereau T, Poirot JL, Guidet B, Kettaneh A, et al. (2007) Severestrongyloidiasis in corticosteroid-treated patients: case series and literature review. J Infect 54: 18-27.

- Guyomard JL, Chevrier S, Bertholom JL, Guigen C, Charlin JF (2007) Finding of Strongyloidesstercoralis infection, 25 years after leaving the endemic area, upon corticotherapy for ocular trauma. J FrOphtalmol 30: e4

- Carvalho EM, Da Fonseca Porto A (2004) Epidemiological and clinical interaction between HTLV-1 and Strongyloidesstercoralis. Parasite Immunol 26: 487-497

- Thompson BF, Fry LC, Wells CD, Olmos M, Lee DH, et al. (2004) The spectrum of GI strongyloidiasis: an endoscopic-pathologic study. GastrointestEndosc 59: 906-910.

- Schaeffer MW, Buell JF, Gupta M, Conway GD, Akhter SA, et al. (2004) Strongyloideshyperinfection syndrome after heart transplantation: case report and review of the literature. J Heart Lung Transplant 23: 905-911

- Stone WJ, Schaffner W (1990) Strongyloides infections in transplant recipients. SeminRespir Infect 5: 58-64.

- Roxby AC, Gottlieb GS, Limaye AP (2009) Strongyloidiasis in transplant patients. Clin Infect Dis 49: 1411-1423.

- Abanyie FA, Gray EB, DelliCarpini KW, Yanofsky A, McAuliffe I, et al. (2015) Donor-derived Strongyloidesstercoralis infection in solid organ transplant recipients in the United States, 2009-2013. Am J Transplant 15: 1369-1375.

- Hamilton KW, Abt PL, Rosenbach MA, (2011) Donor-derived Strongyloidesstercoralis infections in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation 91: 1019-1024.

- Martinez PA, Lopez VR (2015) Is Strongyloidiasis Endemic in Spain? PLoSNegl Trop Dis 9: e0003482.

- Puthiyakunnon S, Boddu S, Li Y, Zhou X, Wang C, et al. (2014) Strongyloidiasis--an insight into its global prevalence and management. PLoSNegl Trop Dis 8: e3018.

- Montes M, Sawhney C, Barros N (2010) StrongylodieSstercoralis: There but Not Seen. CurrOpin Infect Dis 23: 500-504

- Cimino RO, Krolewiecki A (2014) The epidemiology of human strongyloidiasis. Curr Trop Med Rep 1: 216-222

- Dawson-Hahn EE, Greenberg SL, Domachowske JB, Olson BG (2010) Eosinophilia and the seroprevalence of schistosomiasis and strongyloidiasis in newly arrived pediatric refugees: an examination of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention screening guidelines. J Pediatr 156: 1016-1018.

- Genta RM (1989) Global prevalence of strongyloidiasis: critical review with epidemiologic insights into the prevention of disseminated disease. Rev Infect Dis 11: 755-767

- Glinz D, Silue KD, Knopp S, Lohourignon LK, Yao KP, et al. (2010) Comparing diagnostic accuracy of Kato-Katz, Koga agar plate, ether-concentration, and FLOTAC for Schistosomamansoni and soil-transmitted helminths. PLoSNegl Trop Dis 4: e754

- Johnston FH, Morris PS, Speare R, McCarthy J, Currie B, et al. (2005) Strongyloidiasis: a review of the evidence for Australian practitioners. Aust J Rural Health 13: 247-254

- Yori PP, Kosek M, Gilman RH, Cordova J, Bern C, et al. (2006) Seroepidemiology of strongyloidiasis in the Peruvian Amazon. Am J Trop Med Hyg 74: 97-102.

- Moon TD, Oberhelman RA (2005) Antiparasitic therapy in children. PediatrClin North Am 52: 917-948

- Croker C, Reporter R, Redelings M, Mascola L (2010) Strongyloidiasis-related deaths in the United States, 1991-2006. Am J Trop Med Hyg 83: 422-426.

- Wang C, Xu J, Zhou X, Li J, Yan G, et al. (2013) Strongyloidiasis: an emerging infectious disease in China. Am J Trop Med Hyg 88: 420-425.

- Azira NMS, Abdel Rahman MZ, Zeehaida M (2013) Review of patients with Strongyloidesstercoralis infestation in a tertiary teaching hospital, Kelantan. Malaysian J Pathol 35: 71-76

- Schar F, Marti H, Sayasone S, Duong S, Muth S, et al. (2013) Diagnosis, Treatment and Risk Factors of Strongyloidesstercoralis in Schoolchildren in Cambodia. PLoSNegl Trop Dis 7: e2035.

- Khieu V, Schar F, Forrer A, Hattendorf J, Marti H, et al. (2014) High prevalence and spatial distribution of Strongyloidesstercoralis in Rural Cambodia. PLoSNegl Trop Dis 8: e2854.

- Panagiotis K, Ioannis K, Deepa V, Richard D, Margaret CF (2015) Strongyloidiasis in a healthy 8-year-old girl in north-eastern USA Paediatrics and Child Health35: 72-74

- Schär F, Trostdorf U, Giardina F, Khieu V, Muth S, et al. (2013) Strongyloidesstercoralis: Global Distribution and Risk Factors. PLoSNegl Trop Dis 7: e2288.

- Machicado JD, Marcos LA, Tello R, Canales M, Terashima A, et al. (2012) Diagnosis of soil-transmitted helminthiasis in an Amazonic community of Peru using multiple diagnostic techniques. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 106: 333-339.

- Ghoshal UC, Saha J, Ghoshal U, Ray BK, Santra A, et al. (1999) Pigmented nails and Strongyloidesstercoralis infestation causing clinical worsening in a patient treated for immunoproliferative small intestinal disease: two unusual observations. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res 17: 43-45.

- Ghoshal UC, Ghoshal U, Jain M, Kumar A, Aggarwal R, et al. (2002) Strongyloidesstercoralis infestation associated with septicaemia due to intestinal transmural migration of bacteria. J GastroenterolHepatol 17: 1331-1333

- Jeyamani R, Joseph AJ, Chacko A (2007) Severe and treatment resistant strongyloidiasis-indicator of HTLV-I infection. Trop Gastroenterol 28: 176-177.

- Premanand R, Prasad GV, Mohan A, Gururajkumar A, Reddy MK (2003) Eosinophilic pleural effusion and presence of filariform larva of Strongyloidesstercoralis in a patient with metastatic squamous cell carcinoma deposits in the pleura. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci45: 121-124.

- Reddy IS, Swarnalata G (2005) Fatal disseminated strongyloidiasis in patients on immunosuppressive therapy: report of two cases. Indian J DermatolVenereolLeprol 71: 38-40.

- Sathe PA, Madiwale CV (2006) Strongyloidiasishyperinfection in a patient with membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. JPostgradMed 52: 221-222

- Sekhar U, Madan M, Ranjitham M, Abraham G, Eapen G (2000) Strongyloideshyperinfection syndrome-an unappreciated opportunistic infection. J Assoc Physicians India 48: 1017-1019.

- Soman R, Vaideeswar P, Shah H, Almeida AF (2002) A 34-year-old renal transplant recipient with high-grade fever and progressive shortness of breath. J Postgrad Med 48: 191-196.

- Sreenivas DV, Kumar A, Kumar YR, Bharavi C, Sundaram C, et al. (1997) Intestinal strongyloidiasis--a rare opportunistic infection. Indian J Gastroenterol 16: 105-106.

- Ronan SG, Reddy RL, Manaligod JR, Alexander J, Fu T (1989) Disseminated strongyloidiasis presenting as purpura. J Am AcadDermatol 21: 1123-1125.

- Arsic AV, Dzamic A, Dzamic Z, Milobratovic D, Tomic D (2005) Fatal Strongyloidesstercoralis infection in a young woman with lupus glomerulonephritis. J Nephrol18: 787-790

- Weller PF, Leder KL (2015) Strongyloidiasis. Available at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/strongyloidiasis?source=search_result&selectedTitle=1%7E4.

- Asdamongkol N, Pornsuriyasak P, Sungkanuparph S (2006) Risk factors for strongyloidiasishyperinfection and clinical outcomes. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 37: 875-884.

- Lam CS, Tong MK, Chan KM, Siu YP (2006) Disseminated strongyloidiasis: a retrospective study of clinical course and outcome. Eur J ClinMicrobiol Infect Dis 25: 14-18

- Harish K, Sunilkumar R, Varghese T, Feroze M (2005) Strongyloidiasis presenting as duodenal obstruction. Trop Gastroenterol 26: 201-202

- Komenaka IK, Wu GC, Lazar EL, Cohen JA (2003) Strongyloides appendicitis: unusual etiology in two siblings with chronic abdominal pain. J PediatrSurg 38: 8-10

- Csermely L, Jaafar H, Kristensen J, Castella A, Gorka W, et al. (2006) Strongyloides hyper-infection causing life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 12: 6401-6404

- Newberry AM, Williams DN, Stauffer WM, Boulware DR, Hendel-Paterson BR, et al. (2005) Strongyloideshyperinfection presenting as acute respiratory failure and gram-negative sepsis. Chest 128: 3681-3684

- Berk SL, Verghese A, Alvarez S, Hall K, Smith B (1987) Clinical and epidemiologic features of strongyloidiasis. A prospective study in rural Tennessee. Arch Intern Med 147: 1257-1261.

- Kinjo T, Nabeya D, Nakamura H, Haranaga S, Hirata T, et al. (2015) Acute respiratory distress syndrome due to Strongyloidesstercoralis infection in a patient with cervical cancer. Intern Med 54: 83-87.

- Ramdial PK, Hlatshwayo NH, Singh B (2006) Strongyloidesstercoralis mesenteric lymphadenopathy: clue to the etiopathogenesis of intestinal pseudo-obstruction in HIV-infected patients. Ann DiagnPathol 10: 209-214.

- Hsieh YP, Wen YK, Chen ML (2006) Minimal change nephrotic syndrome in association with strongyloidiasis. ClinNephrol 66: 459-463.

- Copelovitch L, Sam Ol O, Taraquinio S, Chanpheaktra N (2010) Childhood nephrotic syndrome in Cambodia: an association with gastrointestinal parasites. J Pediatr 156: 76-81.

- Plata Menchaca, Erika P, de Leon VM, Adriana G, Peña-Romero, et al. (2015) "Pulmonary Hemorrhage Secondary to Disseminated Strongyloidiasis in a Patient with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus." Case Reports in Critical Care.

- Anuradha R, Munisankar S, Dolla C, Kumaran P, Nutman TB, et al. (2015) Parasite Antigen-Specific Regulation of Th1, Th2, and Th17 Responses in Strongyloidesstercoralis Infection. J Immunol 195: 2241-2250.

- Weatherhead JE, Mejia R (2014) Immune Response to Infection with Strongyloidesstercoralis in Patients with Infection and Hyperinfection. Curr Trop Med Rep 1: 229-233

- Pukkila WR, Nardi V, Branda JA (2014) Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 28-2014. A 39-year-old man with a rash, headache, fever, nausea, and photophobia. N Engl J Med 371: 1051-1060

- Ghoshal UC, Alexender G, Ghoshal U, Tripathi S, Krishnani N (2006) Strongyloidesstercoralis infestation in a patient with severe ulcerative colitis. Indian J Med Sci 60: 106-110.

- Murali A, Rajendiran G, Ranganathan K, Shanthakumari S (2010) Disseminated infection with Strongyloidesstercoralis in a diabetic patient. Indian J Med Microbiol 28: 407-408.

- Patil PL, Salkar HR, Ghodeswar SS, Gawande JP (2005) Parasites (filaria&strongyloides) in malignant pleural effusion. Indian J Med Sci 59: 455-456.

- Rajapurkar M, Hegde U, Rokhade M, Gang S, Gohel K (2007) Respiratory hyperinfection with Strongyloidesstercoralis in a patient with renal failure. Nat ClinPractNephrol 3: 573-577.

- Vigg A, Mantri S, Reddy VA, Biyani V (2006) Acute respiratory distress syndrome due to Strongyloidesstercoralis in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 48: 67-69.

- Satyanarayana S, Nema S, Kalghatgi AT, Mehta SR, Rai R, et al. (2005) Disseminated Strongyloidesstercoralis in AIDS: a report from India. Indian J PatholMicrobiol 48: 472-474.

- Bava AJ, Troncoso AR (2009) Strongyloidesstercoralishyperinfection in apatientwithAIDS.JIntAssoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 8: 235-238

- Requena MA, Chiodini P, Bisoffi Z, Buonfrate D, Gotuzzo E, et al. (2013) The laboratory diagnosis and follow up of strongyloidiasis: a systematic review. PLoSNegl Trop Dis 7: e2002.

- Boulware DR, Stauffer WM, Hendel-Paterson BR, Rocha JLL, Seet RC, et al. (2007) Maltreatment of Strongyloides infection: case series and worldwide physicians-in-training survey. Am J Med 120: 545.e1-8.

- Nielsen PB, Mojon M (1987) Improved diagnosis of Strongyloidesstercoralis by seven consecutive stool specimens. ZentralblBakteriolMikrobiolHygA 263: 616-618.

- Kemp L, Hawley T (1996) Clinical pathology rounds. Strongyloidiasis in a hyperinfected patient. Lab Med 27: 237-240

- Siddiqui AA, Gutierrez C, Berk SL (1999) Diagnosis of Strongyloidesstercoralis by acid-fast staining. J Helminthol 73: 187-188

- Goka AK, Rolston DD, Mathan VI, Farthing MJ (1990) Diagnosis of Strongyloides and hookworm infections: comparison of faecal and duodenal fluid microscopy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 84: 829-831.

- Siddiqui AA, Berk SL (2001) Diagnosis of Strongyloidesstercoralis infection. Clin Infect Dis 33: 1040-1047.

- Rodrigues RM, de Oliveira MC, Sopelete MC, Silva DA, Campos DM, et al. (2007) IgG1, IgG4, and IgE antibody responses in human strongyloidiasis by ELISA using Strongyloidesratti saline extract as heterologous antigen. Parasitol Res 101: 1209-1214.

- Ramanathan R, Burbelo PD, Groot S, Iadarola MJ, Neva FA, et al. (2008) A luciferase immunoprecipitation systems assay enhances the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosis of Strongyloidesstercoralis infection. J Infect Dis 198: 444-451.

- Taniuchi M, Verweij JJ, Noor Z, Sobuz SU, Lieshout L, et al. (2011) High throughput multiplex PCR and probe-based detection with Luminex beads for seven intestinal parasites. Am J Trop Med Hyg 84: 332-337.

- Verweij JJ, Canales M, Polman K, Ziem J, Brienen EA, et al. (2009) Molecular diagnosis of Strongyloidesstercoralis in faecal samples using real-time PCR. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 103: 342-346.

- Bosqui LR, Gonçalves AL, Maria do Rosário F, Custodio LA, de Menezes MC, et al. (2015) Detection of parasite-specific IgG and IgA in paired serum and saliva samples for diagnosis of human strongyloidiasis in northern Paraná state, Brazil. Actatropica 150: 190-195.

- Boscolo M, Gobbo M, Mantovani W, Degani M, Anselmi M, et al. (2007) Evaluation of an indirect immunofluorescence assay for strongyloidiasis as a tool for diagnosis and follow-up. Clin Vaccine Immunol 14: 129-133.

- Silva LP, Barcelos IS, Passos-Lima AB, Espindola FS, Campos DM, et al. (2003) Western blotting using Strongyloidesratti antigen for the detection of IgG antibodies as confirmatory test in human strongyloidiasis. MemInstOswaldo Cruz 98: 687-691.

- Thamwiwat A, Mejia R, Nutman TB, Bates JT (2014) Strongyloidiasis as a Cause of Chronic Diarrhea, Identified Using Next-Generation Strongyloidesstercoralis-Specific Immunoassays. Curr Trop Med Rep 1: 145-147

- Hoy AM, Lundie RJ, Ivens A, Quintana JF, Nausch N, et al. (2014) Parasite-derived microRNAs in host serum as novel biomarkers of helminth infection. PLoSNegl Trop Dis 8: e2701.

- Gann PH, Neva FA, Gam AA (1994) A randomized trial of single- and two-dose ivermectin versus thiabendazole for treatment of strongyloidiasis. J Infect Dis 169: 1076-1079.

- WHO (2002) Prevention and control of schistosomiasis and soil transmitted helminthiasis. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available: https://whqlibdoc.who.int/trs/WHO_TRS_912.pdf. Accessed 14 september 20

- Satoh M, Toma H, Sato Y, Takara M, Shiroma Y, et al. (2002) Reduced efficacy of treatment of strongyloidiasis in HTLV?I carriers related to enhanced expression of IFN?γ and TGF?β1. Clinical & Experimental Immunology 127: 354-359.

- Buonfrate D, Requena-Mendez A, Angheben A, Muñoz J, Gobbi F, Van Den Ende J, et al. (2013) Severe strongyloidiasis: a systematic review of case reports. BMC infectious diseases 13: 78.