Keywords

Health system reform, Healthcare management, Organisational transformation, Economic crisis

Introduction

Health system re-organisation is a common approach to healthcare reform aimed at better managing demographic shifts, changes in the health-burden profile, healthcare technologies, public expectations and the need for efficiency and sustainability in health service delivery [1,2]. In line with international trends the Irish health system is undergoing major re-organisation. Some of these changes are driven by the desire to deliver on policy commitments while others are oriented towards greater operational efficiency and coherent service delivery. These organisational changes come on the back of the international financial crisis and its negative impact on health reform in many European countries [2]. This impact, although rooted from 2008 when Ireland reached fiscal crisis point, became clearly apparent in 2012 when indicators of health resourcing and performance showed the health system doing ‘less with less’[3]. Since 2008 health funding was cut by €1.7bn and 12,000 whole time equivalent positions were taken out of the health service. The financial crisis contributed to a health resourcing crisis which in turn further complicated an ongoing organisational crisis. This crisis was manifest in the departure of high calibre professionals from the health system, absenteeism, low staff morale, a blame culture, lack of investment in technology and management systems, and greater levels of bureaucracy, fragmentation and change-fatigue – all outcomes reported in our data.’

These organisational weaknesses evoke some of the failures identified by the Mid-Staffordshire Report [4] and influence concerns for managing patient safety and quality of care, the ability of the system to remain within budget and importantly, to deliver on key reforms [3,5]. The concern of this paper, taking this context into account, is to appraise health system capability for transformation during financial and economic crisis from the perspective of health service managers’. We do this by identifying the priorities, challenges and expectations of health service managers as they work through economic crisis. We then appraise the potential impact of these perspectives using an organisational readiness lens.

Methodology

Conceptual Framework

Previous work assessed the resilience of the Irish Health system in the face of economic crisis, health budget cuts, cost-shifting from government to households and negative performance indicators [6]. This paper develops that analysis by highlighting how healthcare managers’ priorities, challenges and expectations, impact on health system capability for transformation [7,8]. Having identified core themes through content analysis of qualitative data we appraise capability for transformation by examining emergent themes through an organisational readiness lens. We use a four component readiness model that includes the variables of change valence, change efficacy, discrepancy and principal support [9]. Change valence refers to employees’ perception of the benefits for themselves as a result of the planned change; change efficacy refers to employees’ perception of their capability to implement planned changes; discrepancy refers to employees’ belief in the necessity of the change to bridge the gap between an organisation’s current and desired state; and finally principal support refers to employees’ perception of the commitment of formal organisational leaders to support the successful implementation of change.

Data Generation Tools

A survey of 197 health service managers was carried out in late 2013 for which 81 responses met the inclusion criteria generating a response rate of 41%. Respondents were asked to identify government reform priorities, as well as their own managerial, priorities and to calibrate the time they spent on implementing or promoting these. To allow for comparison of prioritisation and time allocation, the research team developed indices from individual responses which revealed how important managers think different priorities are for the government, how important they are for themselves, and the time they spent on them. Respondents were also asked an open-ended question to identify key factors that facilitated or inhibited them in implementing reform.

For more depth of analysis, eighteen qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted with senior managers from across the Irish health system during the period of 2011 to 2014. This paper focusses on the second wave of these conducted in 2014. NVIVO software was used for content analysis and identification of core themes.

Results

Health reform priorities survey

Survey results emphasise the multiplicity of priorities for health service managers. Nineteen different themes were classified by at least six managers as being a priority for government. The top five were:

1. Reducing waiting times in emergency departments

2. Transferring care from hospital to the community

3. Living within budget/austerity measures

4. Money Follows the Patient

5. Driving down the price of drugs

These priorities do not reflect the headline government reforms at the time but seem to relate to running the healthcare system more effectively in the constrained resource environment. The notable exception is Money Follows the Patient (MfTP) which is part of the government reform package. Nevertheless, MfTP can also be seen as a way of making the current system more efficient and may be as much about improving system performance and efficiency as it is about health reform.

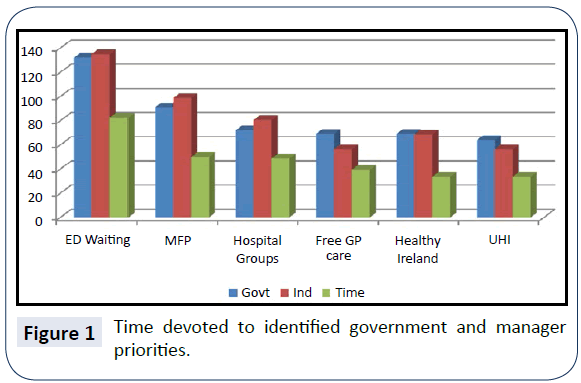

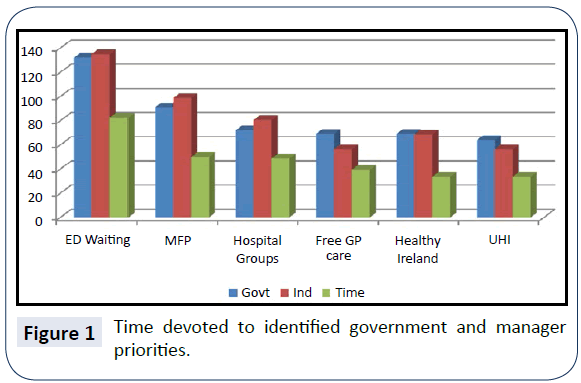

A critical issue therefore is whether the government’s headline reforms are getting the focus they require for full development and implementation? Figure 1 compares time allocated by managers to activities perceived as priorities for government and managers themselves (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Time devoted to identified government and manager priorities.

Despite approximately equal scores registering for perceived government and managers’ priorities, many key reform initiatives are failing to get a proportionate share of managers’ time in practice. The lower time allocation is not a reflection of individual managers valuing things differently from stated priorities. Instead it appears that priority reform activities are being squeezed out. To get an insight into what is displacing stated priorities it is useful to review those activities where time taken is disproportionately higher.

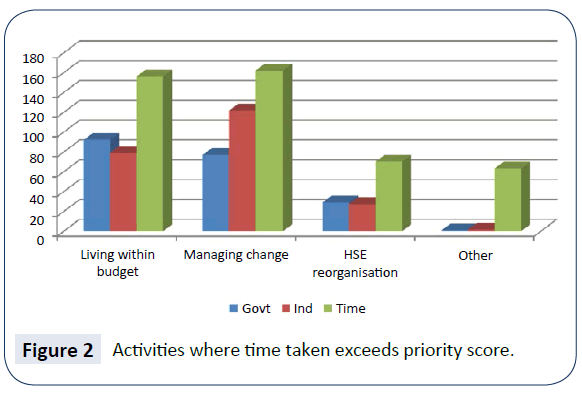

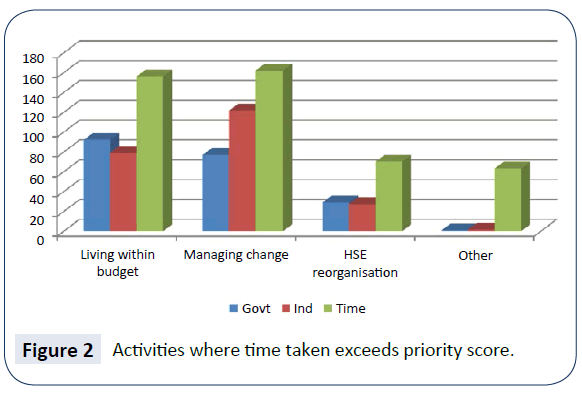

Figure 2 shows health service managers spend much of their time running the current system and the immediate enactment of change-projects in the service of operational efficiency rather than the reform agenda. This imbalance occurs even when managers themselves agree that such activities are of lower priority. Managers report that over 25% of their time is taken up with two activities – living within budget and managing change.

Figure 2: Activities where time taken exceeds priority score.

Given the challenges of implementing major organisational change during economic crisis and austerity, managers were asked to identify factors which inhibited and facilitated positive change. Several factors emerge as critical drags on their ability to work effectively towards positive change. These include insufficient resources and tension between the continuous drive to reform and other competing priorities. This dynamic is further constrained by a lack of clarity on the goals of reform and a sense of disempowerment and lack of recognition of the challenges faced:

“There is no recognition that financial restrictions, ED trolley wait reductions and scheduled care targets are incompatible after six years of cuts.”

The tension is partly due to the scope and extent of priorities and a lack of strategic and implementation planning:

“There are too many major priorities ... [we need to] focus on what is achievable.”

“Government continues to manage change as a result of knee-jerk reactions to particular circumstances. Government policy is developed with no thought given to whether practical implementation is possible - because government and civil servants do not have to implement health policy, the health executive does.”

An absence of a well communicated and sustained vision is also identified:

“A clear plan with timelines and milestones would be helpful as the majority of staff have no real understanding of what the health service will look like, or when it will change.”

“Since I joined the health service the organisation has been in constant flux and change. To date none of the change programmes have been given the chance to bed down.”

These inhibitors are noted repeatedly by managers as failures of adequate resourcing, recognition, communication and leadership, and are judged to result ultimately in a loss of focus on the patient.

Several factors were identified by managers as facilitating the change process. These included team-working, dedicated staff, re-organisation enablers (e.g. public service agreements and clinical care programmes), increased autonomy in some instances and local knowledge and experience. When leadership and vision are present managers feel empowered to participate in the reform process, they value “integrated management [that] listens to other voices and makes the tough decisions.”

Content analysis of manager interviews

On the basis of the health reform priorities survey qualitative interviews with senior healthcare managers working in rural, urban, primary and acute health care settings were conducted. The focal topic emerging from these interviews is the negative impact of constant health service re-organisation. This is noted across three domains of service coordination and delivery:

1. The re-organisation of service coordination (into divisional directorates)

2. The re-organisation of acute care (into seven hospital groups)

3. The re-organisation of primary and social care (into nine community healthcare organisations).

Three cross-cutting themes have been identified in relation to these re-organisation processes: the negative impact on patient care, further fragmentation of an already fragmented system, and the undermining effect of the weak implementation of reform. The challenge of service delivery in a period of economic crisis is pertinent to all these themes, as will be highlighted below.

The negative impact of re-organisation on patient care

Re-organisation for health service reform is difficult but even more so during economic crisis. We note how managers link not only the reduction in resources, but also the establishment of divisional directorates at health service corporate levels with a breakdown of established patterns of patient care. Respondents believe this organisational change is disrupting good working relationships which facilitate the flexible management of patients with complex care needs across healthcare domains. Natural links between the hospital and the primary care service are severed. A number of operational links between hospital and community (e.g. referral paths and local mechanisms for coordination) are threatened due to the establishment of the divisional structure.

“My real fear is for directorates – I’m in a system that’s already quite fragmented; putting those silos in, i.e. directorates silos should really only be a top layer on a whole system, we’ll end up pushing our clients. It may suit the budgets and it may suit management, but it’s not going to suit the clients”. In a tight budgetary climate results and efficiency-orientated organisational models can result in negative patient outcomes and a weakened culture of care [4].

Along with the creation of the divisional directorates, respondents were also concerned for patient care on the basis of reduced resources, both staff and funding. During the crisis managers were expected to meet outpatient waiting list targets with significantly less staff while increasing new services. Respondents pointed out that with the new pressures of population change (increasing numbers of older, chronically ill patients as well as general population growth) safety and quality of care is a big challenge. With staffing numbers down and existing staff under growing stress, managing risk was identified as increasingly difficult and of deep concern. As one respondent noted, “efficiency is being pushed to the limit”. On the basis of this analysis two sub-themes underpin the negative impact on patient care as a result of reorganisation – established care patterns (such as they are) are under threat, and limited resources are putting patients at risk.

Further fragmentation of an already fragmented system as a result of re-organisation

The theme of fragmentation breaks down into three sub-themes, fragmentation in terms of budget and funding management, fragmentation in relation to human resources and staff wellbeing generally, and finally issues relating to system functionality and fragmentation – the latter two being of greater significance than the first. In 2012 hospital managers faced “a tsunami of cuts” while being required to increase productivity and improve services. For voluntary hospitals funding levels were uncertain due to a reduction in privately insured patients and insurance companies withholding payments. The pressure to meet budget targets at year-end resulted in considerable financial challenges including managing large overdrafts. Beyond these operational concerns the key difficulty identified for the emerging structure was the absence of a mechanism that results for managing budgets across the divisional domains. While none of these issues may seem directly related to fragmentation as such, the high levels of financial uncertainty undermine the sense of cohesion, confidence and resilience within the system generally.

Fragmentation resulting from human resource and staff wellbeing challenges feature strongly in respondent’s comments. Staff shortages impact on patient outcomes and the ability of managers to control waiting lists. These were due to a range of measures including a policy of voluntary redundancy, a lack of stable appointments particularly in urban settings, senior managers leaving the system, high levels of absenteeism and a moratorium on civil service hiring across the public service. As well as identifying a lack of skill in working with new management systems and processes, respondents also noted how staffwellbeing is under threat with some managers reporting a sense of isolation and frustration at the lack of recognition by senior management or politicians of either the gravity of the challenges they were facing, nor the successes they achieved in a difficult climate. Respondents noted that although some of the challenges are systemic (e.g. trade union intransigence changes in service delivery practices, a general work culture embedded in disciplinary boundaries making the system inflexible and unresponsive, and a high level of HSE bureaucracy and tardiness in decision-making) their impact is more divisive in a period of economic crisis.

Of particular note in relation to the complexity of managing the different disciplinary boundaries within the system, one respondent noted

“I think working with clinicians is a big challenge; to get them to move on the change agenda, because they like to work within their own environments. A lot of our effort has been actually getting clinicians to change the way they do things. We can get a situation where the whole organisation is up for change, change in processes, but the clinicians, either individually or as a group, have the ability to … thwart change.” The final set of issues relating to fragmentation is the most complex because it refers to system level challenges. The key topic of concern is the impact on patient care of the new divisional structure of the health services as mentioned above – but apart from the threat to patient management between hospital and community (integrated care), respondents also noted how a divisional structure is breaks obvious links within a geographical area, sucks human resources from the periphery to the centre, pushes the management of care pathways lower down in the system where there is less capability to deal with them and creates situations where care delivery changes are implemented in isolation without knowledge of their impact on other settings or system levels. In creating hospital groups as was done in the Irish system, despite some positive outcomes identified, there are real concerns about the de-coupling of acute, primary and community care. For some respondents the identity of small hospitals can be put under serious threat, and it was also noted in one hospital group that a “pressure cooker” situation has been created since the group does not have the capability to serve the needs of its designated population. System level recurring patterns creating on-going fragmentation include a lack of communication and coordination that results in isolation and frustration. Confusion in the reporting structure characterises the lack of communication, as do general bureaucracy and a lack of vision. Respondents talked about the impact of a blame culture and “fire-fighting” that takes energy from strategic work. Aggression within the feedback loop is also identified “from politicians to patients” and undermining any sense of confidence in attempts at health reform. This competitive approach is often associated with performance targets and reporting, and a lack of understanding about how to manage the expectations of different stakeholders: “Within a hospital you’ve got mixed cultures, you’ve got professional groups, doctors, nurses, healthcare professionals, support staff, trade unions, professional bodies, things like the regulators, Medical Council, etc. So you’ve all that pot of things going on within the organisation and you’re trying to manage pathways through that”.

These multiple and complex forms of fragmentation contribute in turn to the difficulty of generating positive organisational change and health service reform.

The undermining effect of the weak implementation of re-organisation

The final core theme is the effect of the weak implementation of re-organisation for health reform; two sub-themes underpin this theme. The first of these reflects a lack of attendance to the change process itself within the system and the ensuing confusion this causes. The second pinpoints a lack of systemlevel planning in relation to the implications of re-organisation and further highlights slow-delivery on key reform components; features which undermine the direction and process of change.

Managers do not have a sense of confidence and trust in reorganisation processes. They report a lack of clarity about the timing and staging of planned changes; a clarity that would enable them to drive and embed the change. One important barrier in this sense is political instability such that implementation of planned changes is not assured, as one hospital group CEO remarked, “I sometimes think; is someone going to saw off the plank behind me?” A culture of blame and scapegoating also impacts on the situation as front line staff are cagey and risk averse. Managers are stressed and unwilling to “go the extra mile”. They report a lack of support from senior leadership in general, and a lack of recognition of the challenges they face. This dynamic generates a sense of instability in a context of constant change which is experienced as a negative spiral. The seemingly unending process of re-organisation that has characterized the Irish Health system since before 2005 has impacted on the ability of people within the system to believe-in and implement those changes.

Along with a lack of trust in the process there is also confusion. The budgetary environment remains unstable. There are systemlevel changes, role-changes and increasing bureaucracy and reporting requirements; all factors generating more “grey space”. Managers reported a lack of clarity about how to address headline delivery problems (e.g. ED wait times) and a lack of interest in these problems from senior leadership. There is confusion about lines of connection (horizontal and vertical) within the divisional structure, and particularly about how the hospital groups are to continue forming in practice. Across a range of challenges that include – the governance pathway towards hospital groups, the position of the hospital boards within these, the status and identity of voluntary hospitals within the groups, the best division of roles, responsibilities and service delivery domains, the pacing of change and the maximizing of the potential of new structures – the ability of personnel to deliver is undermined:

“Our workings with the [Group], trying to find out where we work with regard to that and I suppose the whole governance aspect with regard to that is very, it’s very challenging because there is no roadmap … we were just told we’re reporting to the CEO with regard to finance and we’ve never even received anything on paper with regard to that … it’s just a given and that’s it”.

There is a tension for managers in responding to the vision of service delivery articulated at the ‘centre’ of the system while seeking to maintain what is working well at the ‘periphery’ in local service delivery contexts throughout the country. Managers do not feel included in the planning and implementation process, ideally requiring a lot of positive communication, empowerment, participation and relationship building. The changes demand deep-seated mind-shifts and as such managers feel they should be included more fully. They also feel these changes (such as integrated care delivery) should be modeled at senior divisional directorship level (e.g. integrated reporting to different divisions).

There is a sense among managers that the implications for service delivery arising from the re-organisation projects in train’ are not well thought-through at senior level resulting in slow delivery on change. For example managers highlight how there is a lot of focus on managing trolley numbers in emergency departments without proper resourcing of integrated care plans. The rationale of the re-organisation process is not applied in all its component parts and there is underinvestment in terms of the necessary capital and human resourcing required. For example, the highcalibre people needed to deliver the planned changes in practice are not recruited, as one HSE hospital CEO noted, “public health management is a dirty word”. In sum, a credibility crisis exists due to the slow pace of change, it’s under-resourcing and its lack of coherence.

Taking into account the experience of senior healthcare managers reported here in relation to the consequences of the divisional structuring of the health service for integrated care, the lack of resourcing of both service delivery and the change process itself, the various sources of on-going and increasing system fragmentation, and the confusion and lack of adequate management of health reform and re-organisation processes generally – the capability of the health system for real transformation seems weak.

Organisational readiness as indicator of transformative potential

We now examine manager priorities, challenges and expectations using the organisational readiness framework highlighted earlier for which change valence; change efficacy, discrepancy and principal support are key variables [9]. Managers’ perceptions of the re-organisation processes going-on are an important factor in determining the outcomes of those processes at system, unit and individual levels. Assessing organisational readiness helps determine health system change and reform potential given that organisational transformation requires perceptional as well as practical change [10].

Change valence

None of our respondents identified benefits for themselves in describing the re-organisation process apart from one health service hospital CEO who valued how the hospital group had been successful in securing permission for limited recruitment. When asked what critical changes would make a real difference managers talked principally of changes in communication – its form, type and impact. Given the confusion, lack of clarity and low level of confidence about system reform reflected in the data; it seems that the work to enable managers to identify beneficial outcomes for themselves or their teams is not taking place. The notion of change valence is interesting in that it cites leverage for change in the sense of perceived benefit, as judged by those most closely connected to the change process in practice – the managers of the system and their colleagues. There is not only little sense from managers of this leverage being generated through the re-organisation and reform process, but seemingly a lack of capability within the system to create the conditions through which empowerment can take place.

Change efficacy

Change efficacy denotes employees’ perception of their own capability to implement planned change. Both in earlier interview stages [11] and in the phase of interviews analysed here, managers doubt their capability to implement a whole range of change initiatives. Time and again they cite limitations within the system, in terms of skills, opportunity and extrinsic factors, such that implementing real change is judged improbable. Managers also talk of the failure throughout the crisis to resource change through strategic recruitment and training for leadership and management. Despite noting the goodwill of healthcare staff in “going the extra mile” managers seem to believe that their capability is insufficient for the changes planned.

Discrepancy

Although managers clearly identify dysfunctionality throughout the Irish healthcare system, it is not clear that this belief translates into conviction for the necessity, or direction of the various re-organisation projects in train. There is discrepancy not only between what different stakeholder groups view as the way forward, but more fundamentally in terms of whether a clear vision has been articulated at all. Managers interviewed did not seem to have clarity about a ‘desired state’ for the health system nor about the path towards this state. They speak rather of lacks of understanding, support and communication. While there may be recognition that change is needed – there is no sense of shared vision or of the participation required so that employees can translate and embed the principles of the planned change into local service delivery contexts.

Principal support

The issue of leadership emerges strongly from the data – both survey and interviews. Whether criticized as inculcating a culture of blame, scapegoating or disinterest, or being cited for a range of lacks from communication, to vision, to clarity of purpose and capability, managers do not seem to believe that the level of principal support required for re-organisation and reform exists. There is a lack of confidence among managers about how much leaders are committed to serious implementation given their sense of the limitations of, for example, the political cycle, the focus on quick or popular wins (e.g. wait times), the failure to listen and understand the challenges managers face, and the failure to properly resource the change process itself. Our analysis suggests that sustained commitment to empowering employees at all levels to own and embed the new structures, processes and management systems is a critical determinant of reform success [12].

Given this analysis of little or weak organisational readiness for change it seems that transformational change, particularly in a context of economic crisis, is unlikely. For transformation reorganisation alone is insufficient; attention to the consequences of re-organising actions and more importantly, changes in the underlying meanings of professional work are also key [10]. The re-organisation processes going on in the Irish context may indicate a tendency to do ‘system or structural change’ in the face of crisis rather than analyzing what really needs to change, i.e. embedded cultural habits – the impacts of which are reflected in the research data. There are currently new initiatives in the Irish Health Service to address behavioural and cultural change, but it remains to be seen as to whether these can make a significant impact. System or structural re-organisation is not without cost and can be destabilising as reported in our data, “reform is needed but is poorly directed and implemented, it sucks the life out of the service”. The Francis Report notes that structural change ‘can be counterproductive in giving the appearance of addressing concerns rapidly while in fact doing nothing about the really difficult issues which require long-term consistent management’ [4]. Long-term consistent management is not only a critical challenge for the Irish health system, but across health systems generally. Economic crisis exacerbates this challenge for which there is no easy formula or organisational model.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest a health system failing to generate the resources required for the reform intended with health policy shifts and operational re-organisation in play. Health service managers face a wide range of health system priorities, many of which they could not address due to the demands of managing economic crisis. At another level the challenges managers face are primarily organisational, and they seem to have little expectation or hope that the cultural and practical shifts required to change their organisational realities are possible. The factors inhibiting change offer some insight. Adequately resourcing the change process itself by analysing and understanding in new ways the “really difficult issues” such that manager experience is recognised, communication is prioritised and leadership is developed throughout the system will go some way to making a difference. If there is any hope of real reform these challenges need to be faced in new ways. New forms of communication need to be learnt:

“Now it’s about communication, negotiation, building relationships… if relationships are poor obviously people are going to be reticent, and even where they’re good, if your budget’s under pressure there’s a danger that people get caught in that way.”

Under pressure health budgeting undoubtedly will remain a factor into the future; supporting managers in creating new patterns of communication may go some way towards better outcomes in terms of patient safety, organisational fragmentation and weak implementation processes.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This research was funded by the Health Research Board in Ireland under the research project: Resilience of the Irish Health System – surviving and utilising the economic contraction (grant number: HSR.2010.1 (H01385)

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest

18322

References

- Quaglio G, Karapiperis T, Van Woensel L, Arnold E, McDaid D, et al. (2013) Austerity and health in Europe. Health Policy113:13-9.

- Thomson S, Figueras J, Evetovits T, Jowett M, Mladovsky P, et al. (2014) Economic crisis, health systems and health in Europe: impact and implications for policy - policy summary 12. WHO Regional Office for Europe UN City, Marmorvej 51, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark: World Health Organization.

- Burke S, Thomas S, Barry S, Keegan C (2014) Indicators of health system coverage and activity in Ireland during the economic crisis 2008 to 2014–from ‘more with less’ to ‘less with less’. Health Policy 117:275-8.

- Francis R (2013) Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry - Executive summary. London: The Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry.

- Thomas S, Burke S, Barry S (2014) The Irish health-care system and austerity: sharing the pain. The Lancet. 383:1545-1546.

- Thomas S, Keegan C, Barry S, Layte R, Jowett M, et al. (2013) The Resilience of the Irish Health System: Testing a novel framework for assessment. Health Services Research Vol 13.

- Weiner BJ (2009) A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implementation Science 4:67-75.

- Attieh R, Gagnon MP, Estabrooks CA, Legare F, Ouimet M, et al. (2013) Organizational readiness for knowledge translation in chronic care: a review of theoretical components. Implementation Science 8:138.

- Aarons G, Horowitz JD, Dlugosz LR, Ehrhart MG (2012) The role of organizational processes in dissemination and implementation research. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and implementation research in health - translating science to practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. p. 128-53.

- McNulty T, Ferlie E (2004) Process Transformation: Limitations to Radical Organizational Change within Public Service Organizations. Organization Studies 25:1389-412.

- Burke S, Barry S, Thomas S (2013) Case Study 1: The Economic Crisis and the Irish Health System: Assessing Resilience. In: Hou X, Velényi EV, Yazbeck AS, Iunes RF, Smith O, editors. Learning from Economic Downturns: How to Better Assess, Track, and Mitigate the Impact on the Health Sector. Directions in Development - Human Development. World Bank, Washinton, D.Cpp156-60.

- Davies HTO, Nutley SM, Mannion R (2000) Organisational culture and quality of health care. Quality in Health Care 9:111-9.