Introduction

The International Classification of Headache Disorders is becoming the most important reference document for the management of headache patients [1]. Include several migraine related symptoms or syndromes as migraine related seizure or cyclic vomiting syndrome, but not the migraine associated recurrent vertigo (MARV)?

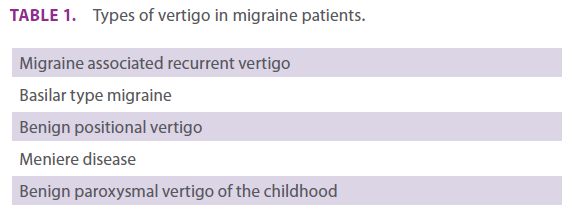

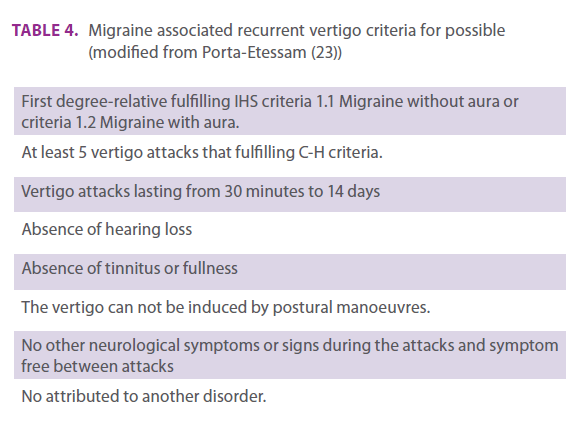

The relationship between vertigo and migraine is well-known since the initial description in 1873 [2]. It has gone beyond the scientific field reaching the literature in the exciting Julio Cortaza´s short tale titled “Cefalea” [3]. Although migraine patients mayn suffer different types of vertigo (table 1), MARV has its own specific clinical features. It is the third cause of consultation for vertigo in a general neurology outpatient clinic [4] and is included as a common cause of recurrent spontaneous vertigo in the neurotological literature [5]. MARV is an entity that needs its own place in the International Classification of Headache Disorders.

Table 1. Types of vertigo in migraine patients.

Delimiting MARV:

MARV differs from other vertigos present in migraine patients and from other types of recurrent vertigos. Most migraine patients experience instability or poor balance sensation during migraine attacks. This multifactor symptom is not vertigo and it differs radically from MARV, where patients suffer motion illusion during the episodes.

The differential diagnosis with benign positional vertigo (BPV), [6] a type of vertigo with an increased incidence in migraine patients (possibly related with utriculus ischemia) [7-8] is necessary. There are two critical differences: MARV attacks last for hours or even days opposed to BPV characterized by short episodes of vertigo lasting seconds or minutes; and BPV is a postural induced vertigo that may be induced by positionalprovoked manoeuvres.

The lack of auditory symptoms is crucial to distinguish MARV from Meniere disease (MD). MD uses to have otological symptoms during the attacks and in the late phase the patients develop a sensorineural deafness. An increase incidence of MD in migraine patients has been reported. Even though a genetic relationship between both entities or an induced mechanism by lowering the “clinical” threshold could justify this association, it is difficult to explain it from a pathophysiology or biological plausibility approach. It is possible that some MD patients were misdiagnosed cases of MARV.

MARV is not a basilar type migraine (BTM). The aura of BTM, typically precede the migraine attack, opposed to MARV where there is not a temporal relationship with the migraine. Florid aura symptoms of BTM are lacking in MARV that may be also associated with migraine without aura [1]. MARV not only differs from BTM in the clinical spectrum but also in the longer duration of the vertigo attacks.

Assuming the relevance of cortical spreading depression, and trigeminal nociception in the pathophysiology of migraine, it’s well known the trigeminal innervations of the crista ampullaris, and there are cortical regions that projects to the brainstem vestibular complex (9-10). The release of neuropeptides into the vestibular peripheral cells or in the vestibular nucleus could precipitate and maintain the vertigo. Even this neuropeptides could sensitized the vestibular system and justify the subclinical vestibular alteration shown in migraine patients [11]. Other explanation of vertigo in migraine patients is the cortical spreading depression. It has been described vertigo episodes as an epileptic symptom and vertigo is one of the features of BTM [1,12]. And finally both syndromes share some features: Are recurrent and chronic, the episodes last from hours to days, and both could be the result of peripheral or/and central neuronal mechanisms.

Neurons in lateral and medial vestibular nucleus respond to serotonin increasing the firing rate and autoradiographic studies confirm the presence of 5-HT 1 and 5-HT2 receptors in the rat vestibular nucleus [13,14]. There are evidences about the participation of glutamate and calcitonin gene-related peptide in the vestibular nerve fibres [15]. The presence of those receptors and neurotransmitters bring nearer again migraine and MARV. There is some controversy about the peripheral or central origin of MARV. The duration of the episodes lasting even days without compensation, the lack of hypoacusia, fullness or tinnitus and the improvement with triptans or migraine-preventive drugs uphold the central-origin hypothesis.

MARV responds to several migraine-preventive drugs [16-20]. Topiramate seems to be an option reducing the frequency of the vertigo attacks [18]. Flunarizine has shown to be an effective treatment for MARV [16-17]. As a personal communication valproic acid also works well in these patients. Acetazolamide a drug effective in familial hemiplegic migraine and episodic ataxia type 2 may be also a useful option in both MARV and migraine with aura [11,21]. The vertigo attacks seem to respond to triptans [22].

Waking through the diagnostic criteria.

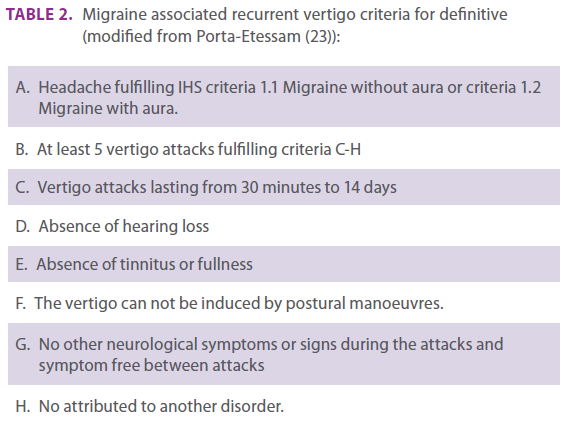

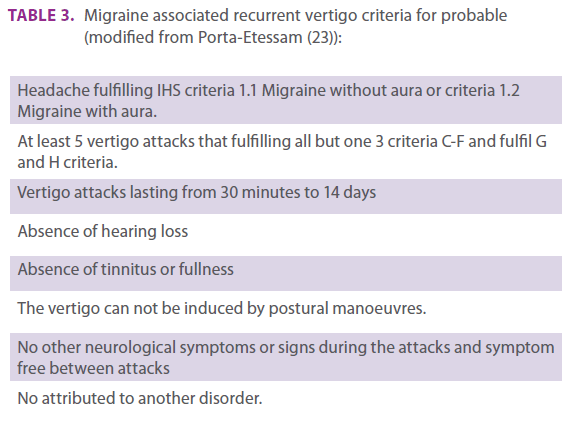

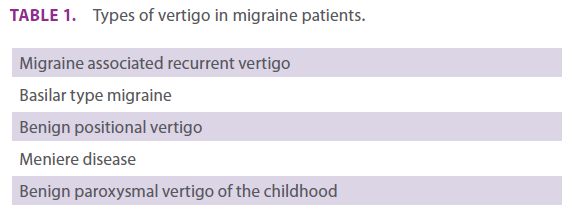

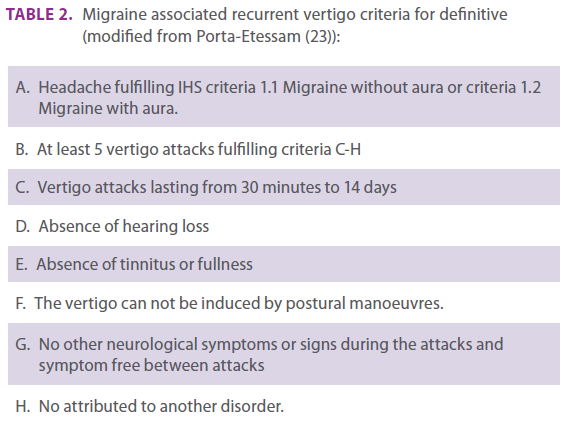

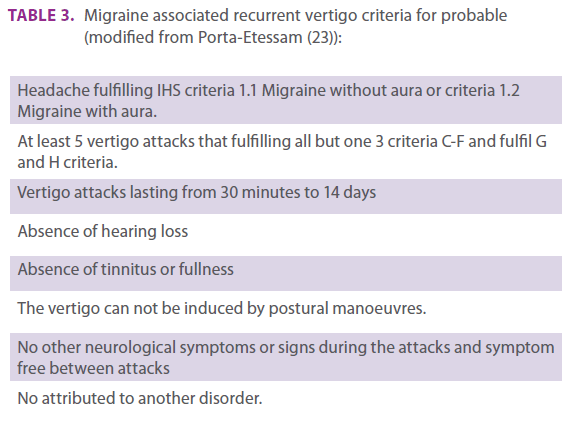

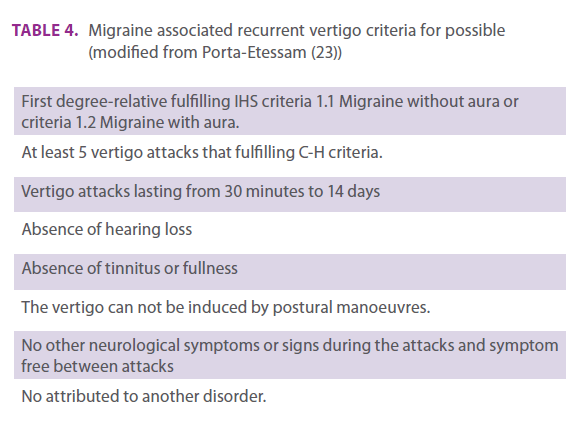

Tables 2, 3 and 4 show the proposed diagnosis criteria divided by definitive, probable and possible.

Table 2. Migraine associated recurrent vertigo criteria for definitive (modified from Porta-Etessam (23)):

Table 3. Migraine associated recurrent vertigo criteria for probable (modified from Porta-Etessam (23)):

Table 4. Migraine associated recurrent vertigo criteria for possible (modified from Porta-Etessam (23))

Conclusions

MARV is an entity that has its own clinical pattern, pathophysiology and treatment. Differential diagnosis should be make with benign positional vertigo, Meniere disease and basilar type migraine. Specific diagnosis criteria could help in its recognition and management.

2215

References

- Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd ed. Cephalalgia 2004; 24 Suppl 1: 1-160.

- Kayan A, Hood JD. Neuro-otological manifestations of migraine. Brain 1984; 107: 1123–1142.

- Cortazar J. Cefalea. En: Cortazar J. Cuentos completos. Madrid: Alfaguara. 1994; 134-143.

- Porta-Etessam J, Martinez-Salio A, Berbel-García A, Ramos A, Millán J, Garcia-Ramos R, Gonzalez-Martinez V. Evaluation of neuro-otology patients in a general neurology office. Journal of Neurology 2003; 250 (SII): 105-106.

- Halmagyi GM, Baloh. Overview of common syndromes of vestibular disease. En: Baloh RW, Halmagyi GM (Eds) Disorders of the Vestibular System. Oxford 1996; 291-299.

- Porta-Etessam J, Martinez-Salio A, Villarejo A et al. Vértigo posicional paroxístico: Un síndrome para detectar, diagnosticar y solucionar. Neurología 2004; 19: 495-496.

- Olsson JE. Neurotologic findings in basilar migraine. Laryngoscope 1991; 101 (S52): 1–41.

- Uneri A. Migraine and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: an outcome study of 476 patients. Ear Nose Throat J. 2004; 83: 814-815.

- Crevits L, Bosman T, Paemeleire K. Migraine related vertigo: The challenge of the basic science. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 2005; 108 :111-112.

- Berthoz A How does the cerebral cortex process and utilize vestibular signals?. En: Baloh RW, Halmagyi GM (Eds) Disorders of the Vestibular System. Oxford 1996; 113-125. Neurology. 2000; 55 :1906-1908

- Harker LA. Migraine-associated Vertigo. En: Baloh RW, Halmagyi GM (Eds) Disorders of the Vestibular System. Oxford 1996; 407-417.

- Kluge M, Beyenburg S, Fernandez G, Elger CE. Epileptic vertigo: evidence for vestibular representation in human frontal cortex. Neurology. 2000; 55: 1906-1908

- Licata F, Li Volsi G, Maugeri G, Santagelo F. Excitatory and inhibitory effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine on the firing rate of medial vestibular nucleus in the rat. Neurosci Lett 1993; 154: 195-198.

- Fonseca MI, Ni YG, Dunning DD, Miledi R. Distribution of serotonin 2A, 2C and 3 receptor mRNA in spinal cord and medulla oblongata. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001; 89: 11-19.

- Wackym PA, Popper P, Micevych PE. Distribution of calcitonin gene-related peptide mRNA and immunoreactivity in the rat central and peripheral vestibular system. Acta Otolaryngol 1993; 113: 601-608.

- de Bock GH, Eelhart J, van Marwijk HW, Tromp TP, Springer MP. A postmarketing study of flunarizine in migraine and vertigo. Pharm World Sci. 1997; 19: 269-274.

- Verspeelt J, De Locht P, Amery WK. Postmarketing study of the use of flunarizine in vestibular vertigo and in migraine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996; 51: 15-22

- Porta-Etessam J, Latorre G, Escribano A, López-de-Silanes C, García-Ramos R, Fernández MJ. Neurology 2008:70, S1P05.036

- Bisdorff AR. Treatment of migraine related vertigo with lamotrigine an observational study. Bull Soc Sci Med Grand Duche Luxemb. 2004; 2: 103-108.

- Porta-Etessam J. Migraña y vertigo. In: Pascual J (Ed). Lectures in cefalea. Current Medicine Group. London 2006: 26-31.

- De Simone R, Marano E, Di Stasio E, Bonuso S, Fiorillo C, Bonavita V. Acetazolamide efficacy and tolerability in migraine with aura: a pilot study. Headache. 2005; 45: 385-856.

- Neuhauser H, Radtke A, von Brevern M, Lempert T. Zolmitriptan for treatment of migrainous vertigo: a pilot randomized placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2003; 60: 882-883.

- Porta-Etessam J. Vértigo asociado a la migraña. Rev Neurol 2007: 44; 490-493.