Christabel C. Enweronu-Laryea1*, Nelson RK. Damale2, Mercy J. Newman3

1MRCP(U.K), MRCPCH(U.K), FGCP Department of Child Health, University of Ghana Medical School, P. O. Box 4236, Accra

2MRCOG (U.K), FGCS Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Ghana Medical School, P. O. Box 4236, Accra

3MSc(London), FWACP, FGCP Department of Microbiology, University of Ghana Medical School, P. O. Box 4236, Accra

- *Corresponding Author:

- Christabel C. Enweronu-Laryea

Department of Child Health, University of Ghana Medical School

P.O. Box 4236, Accra

Phone: +233 20 8154886

E-mail: chikalaryea@yahoo.com

Key words

group B streptococcus, pregnancy, prevalence

Introduction

For over four decades, Streptococcus agalactiae also known as group B streptococcus (GBS) which commonly inhabits the genital, lower urinary and gastrointestinal tracts of pregnant women has been known as a leading cause of perinatal infections [1-2]. It causes chorioamnionitis and endometritis in women and pneumonia, septicemia and meningitis in the newborn. It has also been associated with increased risk of preterm delivery. Maternal carriage of GBS is a prerequisite for early onset disease in the newborn. Infections in the fetus are transmitted vertically via an intact or ruptured amniotic membrane or during passage through a colonized birth canal [3]. Risk of neonatal infection is highest if mothers are colonized with GBS in the third trimester.

Newborn deaths are a major contributor to under 5 years child mortality in Ghana and a limiting factor to the achievement of millennium development goal 4. Infections are a major cause of stillbirths and newborn deaths in Ghana [4]. It is estimated that at least 32% of newborn deaths in Ghana are caused by infections; a significant number of these infections are acquired from the mother. Early onset neonatal infections are potentially preventable and effective intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis has been shown to significantly reduce the morbidity and case-fatality rate for infants at risk [5-6]. It is therefore important to know the antimicrobial susceptibility of organisms that colonize the genital tract of pregnant women over time.

GBS colonization of the genitourinary tract of pregnant Ghanaian women is believed to be rare because of traditional female hygienic practices and the rarity of the organism in isolates from local microbiological laboratories. A literature search revealed very little on GBS in Ghana. We conducted this pilot study using recommended guidelines for GBS microbial isolation to provide accurate baseline data on GBS carriage and antimicrobial sensitivity in pregnant Ghanaian women in 2001. We report our findings to stimulate further research in intrapartum antimicrobial prohylaxis and microbiological causes of newborn deaths in the region.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted at the antenatal clinic of Korle Bu Teaching Hospital (KBTH) in Accra from April to June 2001. KBTH is a tertiary referral hospital for southern Ghana with approximately 900 deliveries per month. Antenatal clinics are held every weekday.

Participants were recruited from the Wednesday antenatal clinic of one of the investigators. About 180 women at all stages of pregnancy attend this clinic each week. General information about the relevance of GBS screening in perinatal care was offered to all women attending a routine morning antenatal care clinic. Consecutive volunteers who met the inclusion criteria (gestational age ≥28weeks + no clinical complaint by the woman) were screened during their turn for consultation with the investigator until a total number of 100 women were recruited. Women with obstetric (e.g. abdominal pain, vaginal discharge) or other clinical (e.g. fever, urinary symptoms) complaints were excluded because the study was focused on GBS carriage in the normal population of pregnant women. A standard questionnaire was used to obtain basic demographic (age and marital status) and obstetric (gestational age and parity) data.

All specimens were collected by the investigator with a sterile cotton applicator. A lower vaginal specimen was taken about 2cm from the introitus and another sterile cotton swab was used to sweep the anorectum. Specimens were inoculated into Todd Hewitt broth (contains 15mg/ml gentamicin and 25μl/ml nalidixic acid) soon after collection at the clinic. After an overnight incubation at 37oC a standard loop (200μl) was used to transfer a loopful of broth and plated on 5% sheep blood agar. These plates were incubated in 5 – 10% CO2 using candle extinction jar at 37oC for 24 hours, and then β-hemolytic colonies which were Gram-positive cocci and catalase-negative were serotyped with Streptex (Plasmatec Laboratory, UK). All GBS isolates were tested for antimicrobial susceptibility to crystalline penicillin.

Categorical variables were compared using chi square test. Differences were considered significant if p<0.05.

Results

There were 2420 antenatal consultations at the Wednesday clinic by women at all stages of pregnancy during the study period. About 32% (781/2420) of the clinic attendants during the period of study were in the third trimester of pregnancy. Even though all the volunteers had no complaint at the time of recruitment, 21 of the 100 women were found to have abnormal vaginal discharge by the investigator during gynecological examination.

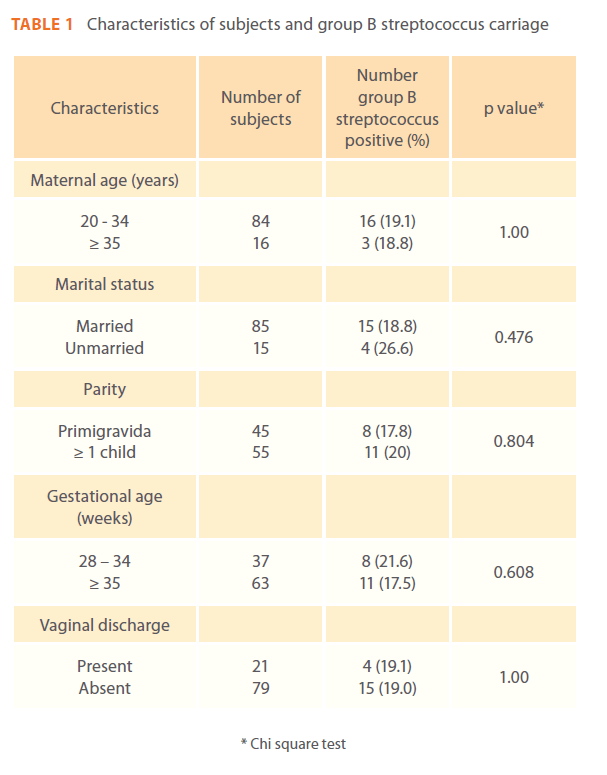

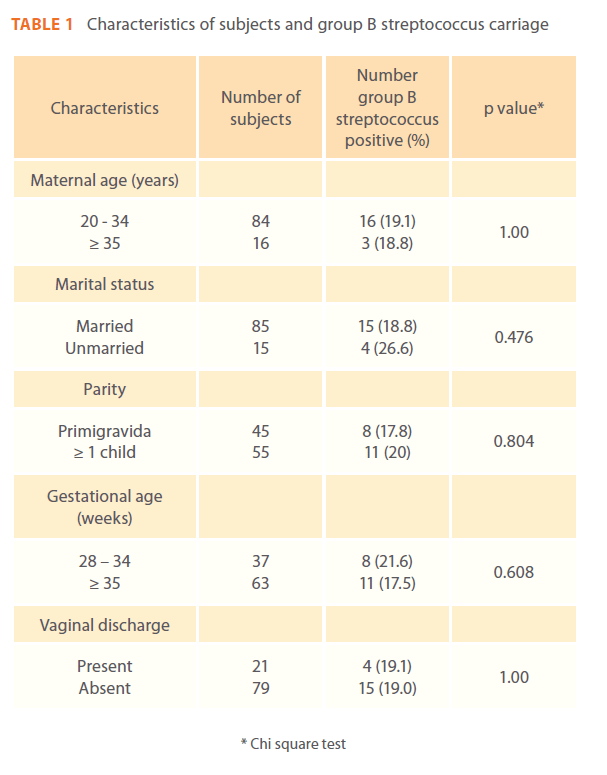

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 100 participants. There was no difference in the marital status, age, parity and gestational age of women colonized with GBS and those who were not. There were 21 isolates from nineteen participants, 12 harbored the organism only in the anorectum, 5 had it only in the genital tract and 2 had GBS at both sites. Nineteen percent (19%) of the participants were colonized with GBS. All isolates were susceptible to crystalline penicillin.

Table 1: Characteristics of subjects and group B streptococcus carriage

Discussion

We have shown that 19% of Ghanaian women in the third trimester of pregnancy in 2001 were colonized with penicillinsensitive GBS. The prevalence of GBS carriage in our study is similar to that described by other studies [7-9] from other parts of the world. Colonization in pregnancy is intermittent but maternal colonization in the third trimester especially after 35 weeks gestation is predictive of neonatal colonization and infection, 17.5% of participants at ≥ 35 weeks gestation were colonized in this study. Current guidelines for cost-effective screening and chemoprophylaxis are from 35weeks gestation of pregnancy [10]. We screened women from 28 weeks gestation because we could not find any published work on GBS colonization or its association with premature births in Ghana.

This pilot study has the inherent limitations of studies with volunteer participants. Though the findings of our work are clinically and epidemiologically relevant no conclusions can be made based on our data because of the small sample size. The inclusion criteria for the study were based on the women’s perception of abnormal symptoms and women with a complaint of abnormal vaginal discharge were excluded. Even though none of the 100 women had any clinical complaint at recruitment, 21% of them were found to have abnormal-looking vaginal discharge during the sampling procedure. This is not an unusual observation in routine clinical practice and sometimes what the obstetrician observes as suspected abnormality yield normal flora on microbiological testing. There was no difference in GBS carriage in these women compared to those without vaginal discharge in this study.

No conclusions can be made on the correlation of colonization with maternal age and marital status, gestational age, parity or vaginal discharge because of the small number of subjects in this cohort. However other studies [11-12] have not found a strong association between these factors and GBS colonization. Vertical transmission of GBS to the newborn occurs in 40 – 73% of culture positive women but only 2% of these infants develop early-onset disease [13]. However, the risk of disease can increase up to 35 fold in the event of risk factors including prolonged rupture of membranes, intrapartum fever and low birth weight. These risk factors are not uncommon in Ghanaian pregnant women.

The microbiological findings of our study are similar to those of Badri et al [14] and Quinlan et al [15] who also cultured more GBS from the anorectum than the genital tract. This lower yield of the genital tract can be explained by our sampling of only the lower vagina. In the study by Anthony et al [16] the cotton swab for sampling the lower vagina was used to swab the periurethral area and medial aspects of labia majora and they obtained almost identical isolates from the anorectal and genital cultures. Cultures from both sites are recommended because the anorectum may provide a reservoir for intermittent genitourinary tract re-colonization. All the isolates of GBS in our study were susceptible to penicillin G as observed in other studies [17-19]. However, the susceptibility pattern of GBS in Ghanaian women presently may be different from the findings of this study in 2001 because of increased use and misuse of antibiotics inherent in many developing countries.

There is no established protocol for screening or prevention of GBS disease in Ghana. The common practice for microbiological testing in Ghanaian pregnant women involves the collection of a high vaginal swab specimen that is transported to a laboratory for plating on solid media. This method fails to identify GBS in many women harboring the organism. We have shown that maternal carriage of GBS is not rare in women attending antenatal clinic at KBTH. The supposed rarity of GBS in Ghana is most likely due to inadequate microbiological methods. A large multicentre study using the recommended microbiological methods and wider spectrum of antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates is recommended.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Francis Codjoe of the Department of Microbiology of KBTH for his technical assistance and Elizabeth Amui of the Department of Obstetrics for her help in the recruitment of the women.

Author’s contribution

All 3 authors worked together in the design of the study, NRK Damale recruited the subjects and collected the specimens, MJ Newman organized the laboratory investigations. CC Enweronu-Laryea wrote the draft manuscript and all 3 authors reviewed the manuscript before submission for publication

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this work

222

References

- Anthony BF, Okada DM, Hobel CJ (1978) Epidemiology of group B streptococcus: longitudinal observations during pregnancy. J Infect Dis 137: 524-530.

- Nandyal RR (2008) Update on group B streptococcal infections: perinatal and neonatal periods. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 22(3): 230-7.

- Pass MA, Gray BM, Khare S, Dillon HC (1979) Prospective studies of group B streptococcal infections in infants. J Pediatr 95: 437- 443.

- Edmond KM, Quigley MA, Zandoh C, Danso S, Hurt C, et al (2008) Aetiology of stillbirths and neonatal deaths in rural Ghana: implications for health programming in developing countries. PaediatrPerinatEpidemiol 22(5): 430-7.

- Dermer P, Lee C, Eggert J, Few B (2004) A history of neonatal group B streptococcus with its related morbidity and mortality rates in the United States. J PediatrNurs 19(5): 357-63.

- Vergani P, Patanè L, Colombo C, Borroni C, Giltri G, et al (2002) Impact of different prevention strategies on neonatal group B streptococcal disease. Am J Perinatol 19(6): 341-8.

- Stoll BJ, Schuchat A (1998) Maternal carriage of group B streptococcus in developing countries. Pediatr Infect Dis J 17(6): 499-503.

- Faye-KetteAchi H, Dosso M, Kacou A, Akoua-Koffi G, Kouassi A, et al (1991) Genital carriage of Streptococcus group B in the pregnant woman in Abidjan (Ivory Coast). Bull SocPatholExot 84(5 Pt 5): 532-9.

- Barcaite E, Bartusevicius A, Tameliene R, Kliucinskas M, Maleckiene L, et al (2008) Prevalence of maternal group B streptococcal colonisation in European countries. ActaObstetriciaetGynecologicaScandinavica 87(3): 260-271.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2002) Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease. Revised guideline from CDC. MMWR Recomm Rep 51(RR-11): 1-22.

- Zusman AS, Baltimore RS, Fonseca SNS (2006) Prevalence of maternal group B streptococcal colonization and related risk factors in a Brazilian population. Braz J Infect Dis 10(4): 242-6.

- Regan JA, Klebanoff MA, Nugent RP (1991) The epidemiology of group B streptococcal colonization in pregnancy. ObstetGynecol 77(4): 604-10.

- Baker CJ, Edwards MS (1988) Group B streptococcal infections: perinatal impact and prevention methods. Ann N Y AcadSci 549: 193-202.

- Badri MS, Zawaneh S, Cruz AC, Mantilla G, Baer H, et al (1977) Rectal colonization with group B streptococcus: relation to vaginal colonization of pregnant women. J Infect Dis 135(2): 308- 312.

- Quinlan JD, Hill DA, Maxwell BD, Boone S, Hoover F, et al (2000) The necessity of both anorectal and vaginal cultures for group B streptococcus screening during pregnancy. J FamPract 49(5): 447-8.

- Anthony BF, Eisenstadt R, Carter J, Kim KS, Hobel C J (1981) Genital and intestinal group B streptococci during pregnancy. J Infect Dis 143: 761-766.

- Simoes JA, Aroutcheva AA, Heimler I, Faro S (2004) Antibiotic resistance patterns of group B streptococcal clinical isolates. Infect Dis ObstetGynecol 12(1): 1-8.

- Panda B, Iruretagoyena I, Stiller R, Panda A (2009) Antibiotic resistance and penicillin tolerance in ano-vaginal group B streptococci. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 22(2): 111-4.

- Gray KJ, Bennett SL, French N, Phiri AJ, and Graham SM (2007) Invasive group B streptococcal infection in infants, Malawi. Emerg Infect Dis 13(2): 223–229.