Key words

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), memantine, caregiver, psychiatric symptoms, behaviour, post-marketing study

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative condition, which initially damages the medial structures of temporal lobes, resulting in a memory deficit. With time, the memory deficit increases, and brain damage extends throughout the temporal lobes, the frontal lobes and associated cortices, and finally results in an aphasic-apraxic-agnosic syndrome. In addition, psychiatric and behavioural symptoms are characteristic of AD, and are present in almost all patients. Overall, 92% of AD patients experience at least one psychiatric or behavioural symptom, 81% have two or more symptoms, and 51% have four or more symptoms (Finkel, 2003). Psychiatric and behavioural symptoms have an impact on caregiver distress that appears to be greater than that of cognitive and functional impairment (Craig et al., 2005; Artaso et al., 2001; Ferris et al., 1987; Borrie et al., 2006; Kaufer et al., 1998). In particular, delusions (Riello et al., 2002), sleep disorders (McCurry et al., 1999), and agitation/ aggression (Borrie et al., 2006) have been reported as the most distressing symptoms for the caregiver. Furthermore, there is evidence that caregiver distress may, in turn, influence patient mood and behaviour (Riello et al., 2002). In clinical practice, it would be desirable to employ a systematic approach for the management of these symptoms (Robinson et al., 2001; Hosaka and Sugiyama, 1999), as it is clear that their effects are wide-ranging, impacting not only on patients, but also their caregivers/family members.

Memantine, an uncompetitive N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamatergic receptor antagonist, has been approved for the treatment of moderate to severe AD in more than 70 countries worldwide. The efficacy of memantine on global performance, cognition, and function, as well as its good tolerability, have been demonstrated in clinical studies of patients with AD (Reisberg et al., 2003; van Dyck et al., 2007; Tariot et al., 2004; Robinson and Keating, 2006; Bakchine and Loft, 2008; Peskind et al., 2006; Winblad et al., 2007). However, memantine has also shown efficacy in the treatment of the psychiatric and behavioural aspects of AD (Gauthier et al., 2007).

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) (Cummings, 1997; Cummings et al., 1994; Vilalta-Franch et al., 1999) is a useful instrument to assess the response of neuropsychiatric symptoms to treatment strategies in dementia. This post-marketing study was designed to evaluate the effect of memantine on each NPI symptomatic domain, and on consequent caregiver distress. The study also aimed to assess the use of other drugs for the treatment of psychiatric symptoms (neuroleptics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines) in patients receiving memantine treatment.

Methods

Patients

Patients were enrolled at three study centres in Spain from September 2006 to March 2007, and were entered into the study at the time of treatment initiation with memantine. Patients and their caregivers provided informed consent for entry into the study.

Inclusion criteria were: diagnosis of probable AD according to NINDS-ADRDA criteria; MMSE 5–20 or GDS stages 5–6, inclusive (i.e., moderate to severe disease); recent (within 12 months) MRI or CT scan consistent with a diagnosis of AD; age ≥60 years; intention of treatment initiation with memantine; residence in the community; collaboration of the patient’s main caregiver. In all cases, the diagnosis of AD was made clinically through neuropsychological assessment, and exclusion of other possible causes in accordance with the recommendations of the American Academy of Neurology Quality Standards Subcommittee (Knopman et al., 2001).

Exclusion criteria were: clinically significant vitamin B12 or folate deficiency; active pulmonary, gastrointestinal, renal, hepatic, endocrine or cardiovascular disease or other psychiatric or central nervous system disorders; treatment with unstable doses of antidepressants, antipsychotics or benzodiazepines in the 2 months prior to study enrolment. However, patients on stable doses of these medications prior to the study were included, with any medication changes permitted and recorded during the study.

Treatment

Treatment with 20 mg/day memantine (tablets/solution) was prescribed to all patients in the study, including a 3-week dosetitration schedule in accordance with the standard recommendations of the memantine Summary of Product Characteristics. Investigators were allowed to modify this schedule on a perpatient basis for tolerability reasons.

Outcome measures

The main outcome measures of the study were change from baseline in two validated variants of the NPI (Cummings et al., 1994; Cummings, 1997; Vilalta-Franch et al., 1999): the NPIquestionnaire, NPI-Q (Boada et al., 2002; Kaufer et al., 2000), to assess patients’ psychiatric and behavioural symptoms, and the NPI caregiver distress scale, NPI-D (Kaufer et al., 1998), to assess the impact of psychiatric and behavioural symptoms on caregiver distress. These NPI assessments are standardised caregiver interviews that examine 12 individual behavioural domains: delusions, hallucinations, agitation/aggression, depression/ dysphoria, anxiety, euphoria/elation, apathy/indifference, disinhibition, irritability/lability, aberrant motor behaviour, night-time behavioural disturbances, and appetite/eating changes. Each domain of the NPI-Q is rated for frequency (1–4) and severity (1–3), and the overall score for a domain is the product of frequency and severity (Boada et al., 2002). On the NPI-D, each domain is rated for level of caregiver distress (0–5) (Kaufer et al., 1998). The NPI total scores are the sum of the individual domain scores, with higher scores indicating more serious behavioural symptoms (NPI-Q) or greater caregiver distress (NPI-D). No cutting-point or reference values exist for this scale.

Patients and their caregivers attended two visits – a pre-treatment visit at the point of inclusion into the study (baseline), and a post-treatment visit after 4 (±1) months of memantine treatment (endpoint). The NPI-Q and NPI-D total and individual domain scores were assessed at both visits.

The initiation, withdrawal, and dose increase/decrease of neuroleptics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines were also examined as an exploratory study endpoint during the memantine treatment period. Other changes in medication were also recorded.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v14.0. Parametric tests were used since the sample follows a normal distribution. A Student (paired) t-test analysis was used to compare differences between the treatment means at baseline and endpoint for each NPI-Q and NPI-D domain. The null-hypothesis of equal means (baseline vs endpoint) was tested on a level of significance of 0.05 (two-sided). Two-sided 95% confidence intervals were also used to describe the effects.

Differences between the number of patients receiving concomitant medications at endpoint and at baseline were analysed using a Chi-square test. Sample-size determination: N = [(Za + Zß)2 • DEd2 ] / dif2 = 130

Results

Patients

In total, 150 patients were enrolled in the study – 67 men and 83 women. The age range was 67–91 years, with a mean age of 78.46 years (SD: 8.05) and, at baseline, the median MMSE score was 16, and the median GDS score was 5. No patients required permanent treatment withdrawal during the study period. Treatment was temporarily withdrawn due to hospital admission in two patients, but the initial treatment schedule was resumed after discharge. At endpoint, 82% of patients were receiving full doses of memantine (20 mg/day), and the mean dose was 17.20 mg/day (SD: 4.34).

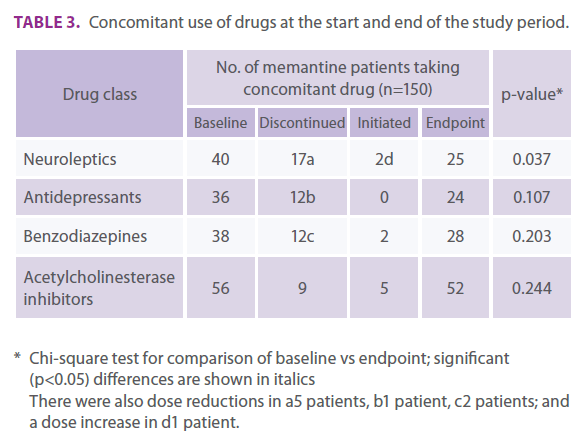

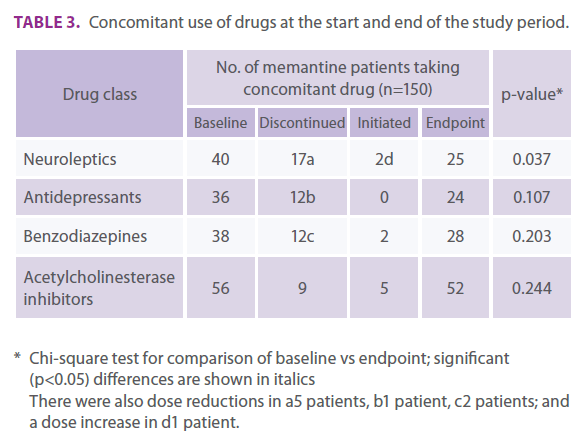

Regarding concomitant medications at baseline, 40 patients were taking neuroleptics, 36 patients were taking antidepressants, 38 patients were taking benzodiazepines, and 56 patients were taking acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.

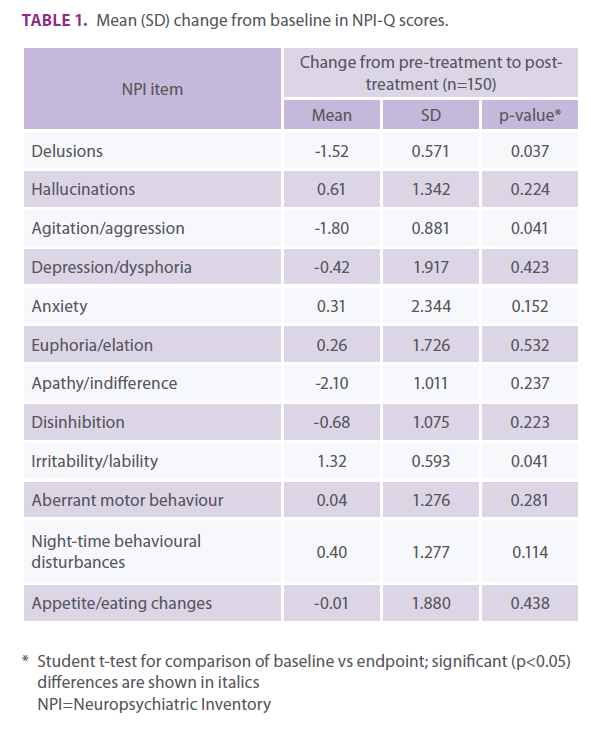

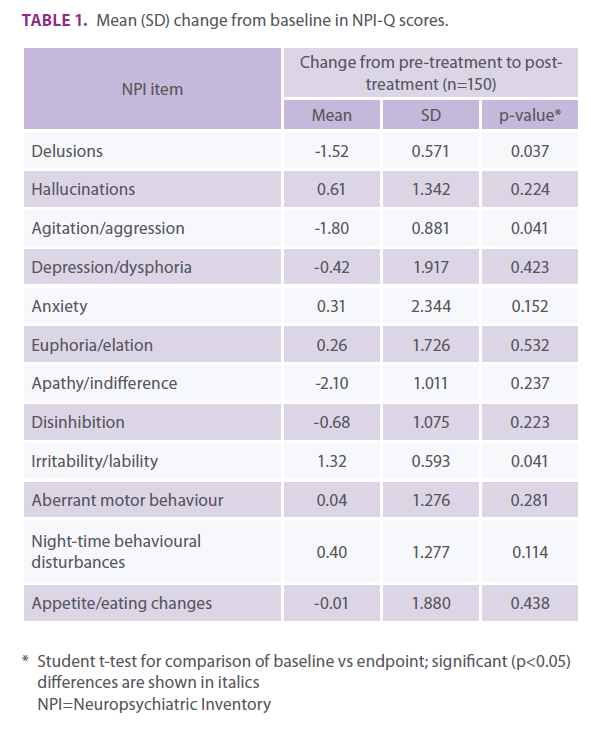

Effect of treatment on patients

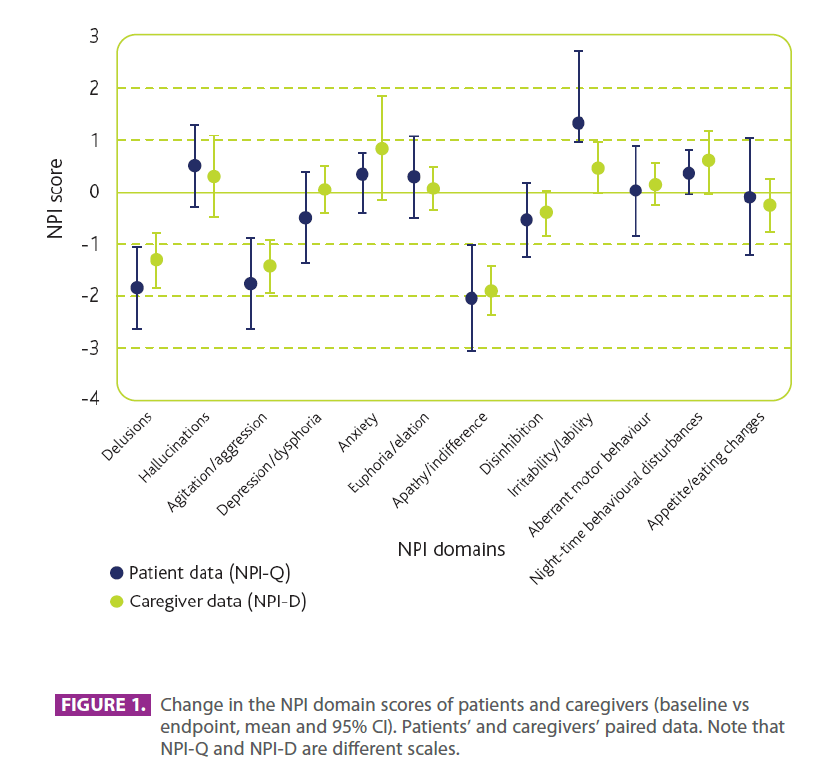

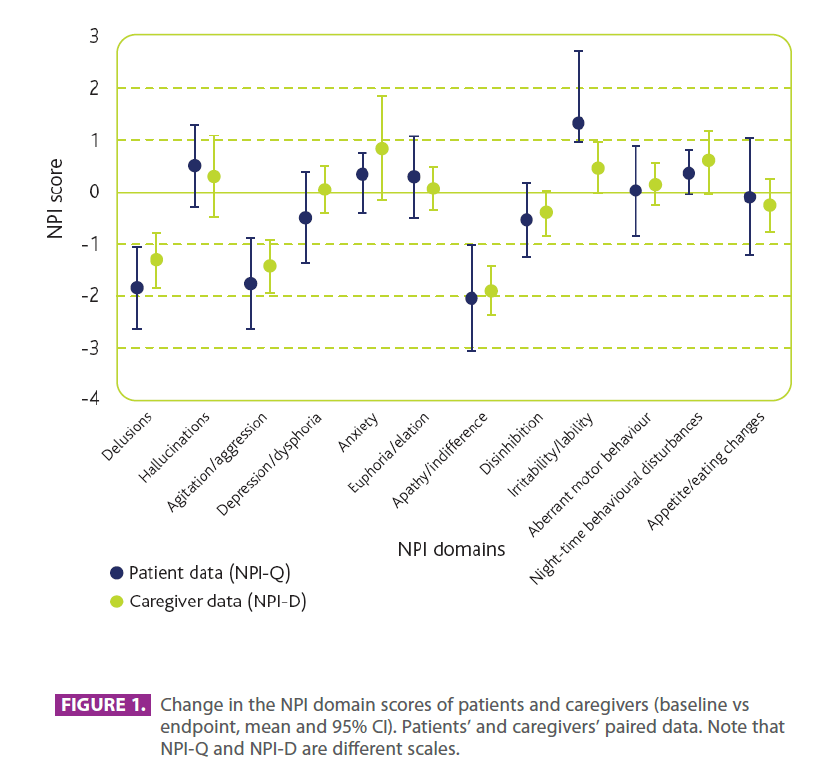

The mean change from baseline in NPI-Q total score was -0.85 (SD: 0.598; p=0.141). From baseline to endpoint, statistically significant benefits (i.e., score reductions) were observed in the NPI-Q domains of delusions (p=0.037), and agitation/aggression (p=0.041), with a marked (but non-significant) decrease in apathy/indifference (Table 1). A statistically significant worsening (i.e., score increase) was observed in the irritability/lability domain (p=0.041). No statistically significant differences were observed for other domains.

Table 1. Mean (SD) change from baseline in NPI-Q scores.

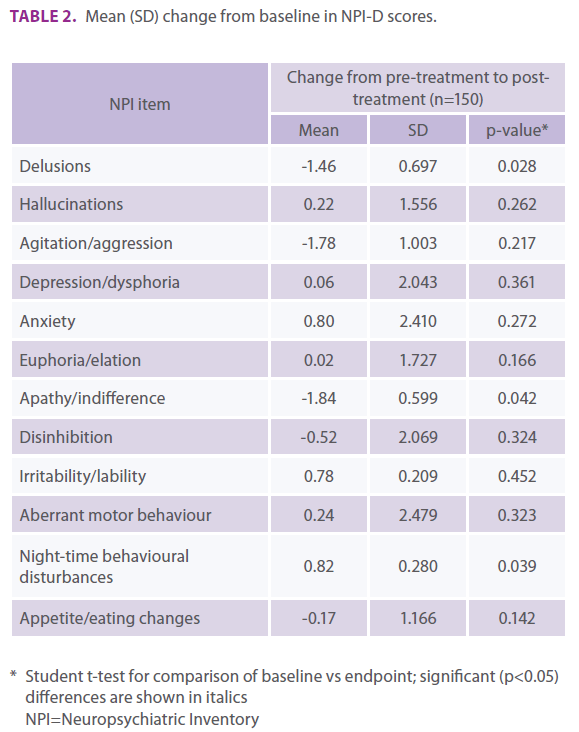

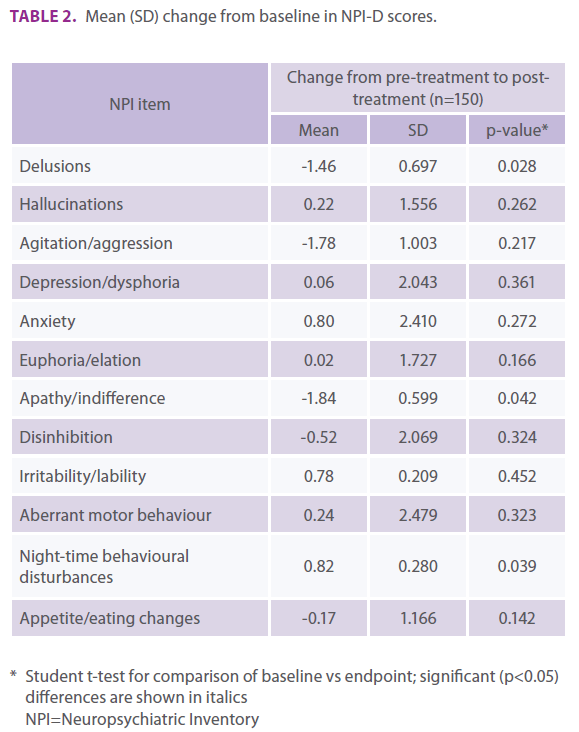

Repercussion on caregiver distress

The mean change from baseline in NPI-D total score was -0.85 (SD: 0.618; p = 0.215). Statistically significant benefits (i.e., score reductions) were observed in the NPI domains of delusions (p = 0.028) and apathy/indifference (p=0.042), with a marked (but non-significant) decrease in mean agitation/aggression score (Table 2). A statistically significant worsening (i.e., score in- crease) was observed in the domain of night-time behavioural disturbances (p = 0.039). No significant differences were obtained in the other domains.

Table 2. Mean (SD) change from baseline in NPI-D scores.

Concomitant treatments

The comparison between the number of patients receiving concomitant drug classes at baseline and endpoint is shown in Table 3. Of the 40 patients receiving neuroleptic treatment at baseline, treatment was withdrawn in 17 patients at endpoint, the dose was reduced in five patients and increased in one patient, and two patients not receiving neuroleptics at baseline had initiated neuroleptic treatment during the study. Significant differences were observed in the number of patients who received neuroleptics at the study endpoint vs baseline (Table 3).

Table 3. Concomitant use of drugs at the start and end of the study period.

There were no significant differences between baseline and endpoint in the number of patients receiving antidepressants, benzodiazepines, or acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (Table 3).

Discussion

Memantine, both as monotherapy and as combination therapy with donepezil, has shown global efficacy in the management of psychiatric and behavioural symptoms in moderate to severe AD, as confirmed by a meta-analysis of six clinical studies (Winblad et al., 2007). Post hoc and pooled analyses have also demonstrated the benefits of memantine on specific behavioural items (Gauthier et al., 2005; Gauthier et al., 2007; Wilcock et al., 2008). However, no previous study has been prospectively designed to investigate the effect of memantine on individual NPI domains/symptoms, or assess how such benefits may impact upon caregiver distress. In the current post-marketing investigation, memantine produced an important improvement for patients in the NPI domains of delusions, agitation/aggression, and apathy/indifference, while a worsening was observed in irritability/ lability. No relevant changes were observed for other symptomatic domains.

Figure 3.Change in the NPI domain scores of patients and caregivers (baseline vs endpoint, mean and 95% CI). Patients’ and caregivers’ paired data. Note that NPI-Q and NPI-D are different scales.

Regarding the improvement in the agitation/aggression domain a notable correlation was observed between our data and those from a post hoc analysis of data from two memantine clinical studies (Reisberg et al., 2003; Tariot et al., 2004), which also assessed the individual NPI domains in patients with moderate to severe AD (Gauthier et al., 2005). However, in contrast, results from the post hoc analysis and other studies observed benefits of memantine on irritability/lability symptoms (Olin and Cummings, 2006; Tariot et al., 2006; Cummings and Olin, 2006; Gauthier et al., 2005), while a worsening of symptoms was seen here. This symptomatic worsening may be linked to the marked reduction in apathy/indifference produced by memantine, which could potentially impact on patient irritability.

As expected, the NPI items for which a treatment-related benefit had repercussions on caregivers occurred in similar domains to those obtained for patient symptoms, with caregivers experiencing less distress due to patient delusions, agitation/ aggression, and apathy/indifference. A correlation between patient agitation/aggression and caregiver distress has been demonstrated in previous studies (Craig et al., 2005; Borrie et al., 2006). A positive effect on these symptoms has also been observed with anticholinergic drug treatment (Cummings et al., 2004; Holmes et al., 2004; Cummings et al., 2006; Aupperle et al., 2004), although the therapeutic effect on aggression/agitation was not as pronounced. The exception to the patient– caregiver correlations in this study was night-time behavioural disturbances. For this symptomatic domain, the results indicated that memantine was associated with a significant negative effect on caregivers – a non-significant worsening of patients was observed in this domain.

Memantine was also associated with a worsening of patient irritability/ lability, but although this did cause a numerical worsening in caregiver score, the impact was not found to be statistically significant. Thus, the effects of memantine show parallel trends in patients and caregivers, although these trends do not always reach statistical significance in both groups.

The psychiatric and behavioural symptoms of AD result in a substantial increase in the indirect costs of the disease (Butman et al., 2004) and, of all symptoms, agitation/aggression is the most frequent determinant of patient institutionalisation (Ferris et al., 1987). Therefore, by relieving these symptoms, memantine treatment could be expected to help reduce resource consumption and health costs. Furthermore, it is important to note that, as previously shown (Shua-Haim et al., 2006), treatment with memantine in this study reduces the need for neuroleptic drug consumption, and therefore any associated adverse effects, and direct and indirect costs. Overall, these benefits are consistent with results from an earlier pharmacoeconomic study, in which memantine monotherapy was associated with significant reductions in caregiver time and direct costs, as well as in social costs and time to institutionalisation (Wimo et al., 2003).

Conclusions

In this open-label study memantine treatment significantly improved psychiatric and behavioural symptoms related to delusions and agitation/aggression, and worsened irritability/ lability, in patients with moderate to severe AD. In addition, memantine reduced the caregiver distress associated with patient delusions and apathy/indifference. However, it also negatively affected caregiver distress linked to patients’ nighttime behavioural disturbances. In addition, study indicates that memantine reduces the need for neuroleptic drug treatment related to baseline.

2209

References

- Artaso B, Goñi A, Gómez AR. 2001. Factores influyentes en la sobrecarga del cuidador informal del paciente con demencia. Rev Psicogeriatría 1: 18–22. [In Spanish]

- Aupperle PM, Koumaras B, Chen M, et al. 2004. Long-term effects of rivastigmine treatment on neuropsychiatric and behavioural disturbances in nursing home residents with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease: results of a 52 weeks open-label study. Curr Med Res Opin 20(10): 1605–1612.

- Bakchine S, Loft H. 2008. Memantine treatment in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled 6-month study. J Alzheimers Dis 13(1): 97–107. [Corrected and republished from: Bakchine S, Loft H. 2007. J Alzheimers Dis 11(4): 471–479.]

- Boada M, Cejudo JC, Tàrraga L, et al. 2002. Neuropsychiatric inventory questionnaire (NPI-Q): Spanish validation of an abridged from of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI). Neurología 17(6): 317–323. [In Spanish]

- Borrie M, Smith M, Sambrook R, et al. 2006. Caregiver burden: data from the Canadian outcomes study in dementia (COSID). Poster presented at the 9th International Geneva/Springfield Symposium on Advances in Alzheimer Therapy. April 19–22, Geneva, Switzerland. 38.

- Butman J, Loñ L, Serrano C, et al. 2004. Impacto de los síntomas neuropsiquiátricos en los costes económicos de la enfermedad de Alzheimer. Revista Argentina de Neuropsicología 3: 6. [In Spanish]

- Craig D, Mirakhur A, Hart DJ, et al. 2005. A cross-sectional study of neuropsychiatric symptoms in 435 patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 13(6): 460–468.

- Cummings JL. 1997. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: assessing psychopathology in dementia patients. Neurology 48(6): 10–16.

- Cummings JL, Olin JT; for the Memantine MEM-MD-02 Study Group. 2006. The effect of memantine on distinct behavior syndromes in moderate to severe AD patients. Poster presented at the 9th International Geneva/Springfield Symposium on Advances in Alzheimer Therapy. April 19–22, Geneva, Switzerland. 51.

- Cummings JL, McRae T, Zhang R; Donepezil-Sertraline Study Group. 2006. Effects of donepezil on neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia and severe behavioral disorders. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 14(7): 605–612.

- Cummings JL, Schneider L, Tariot PN, et al. 2004. Reduction of behavioural disturbances and caregiver distress by galantamine in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 161(3): 532–538.

- Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al. 1994. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 44(12): 2308–2314.

- Ebixa® (memantine). Summary of product characteristics. H. Lundbeck A/S, 2007.

- Ferris SH, Steinberg G, Shulman E, et al. 1987. Institutionalization of Alzheimer’s disease patients: reducing precipitating factors through family counseling. Home Health Care Serv Q 8(1): 23–51.

- Finkel SI. 2003. Behavioral and psychologic symptoms of dementia. Clin Geriatr Med 19(4): 799–824.

- Gauthier S, Wirth Y, Möbius HJ. 2005. Effects of memantine on behavioural symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease patients: an analysis of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) data of two randomised, controlled studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 20(5): 459–464.

- Gauthier S, Loft H, Cummings J. 2007. Improvement in behavioural symptoms in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease by memantine: a pooled data analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry [Epub ahead of print].

- Holmes C, Wilkinson D, Dean C, et al. 2004. The efficacy of donepezil in the treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 63(2): 214–219.

- Hosaka T, Sugiyama Y. 1999. A structured intervention for family caregivers of dementia patients: a pilot study. Tokai J Exp Clin Med 1999; 24(1): 35–39.

- Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, et al. 2000. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 12(2): 233–239.

- Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Christine D, et al. 1998. Assessing the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Caregiver Distress Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 46(2): 210–215.

- Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL, et al. 2001. Practice parameter: diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review): report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 56(9): 1143–1153.

- McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Teri L, et al. 1999. Characteristics of sleep disturbance in community-dwelling Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1999; 12(2): 52–59.

- Olin JT, Cummings JL; for the Memantine MEM-MD-02 Study Group. 2006. Meta-analysis of Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) domains in three 6-month trials of memantine in moderate to severe AD. Poster presented at the 9th International Geneva/ Springfield Symposium on Advances in Alzheimer Therapy. April 19–22, Geneva, Switzerland. 50.

- Peskind ER, Potkin SG, Pomara N, et al. 2006. Memantine treatment in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: a 24-week randomized, controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 14(8): 704– 715.

- Reisberg B, Doody R, Stöffler A, et al; Memantine Study Group. 2003. Memantine in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 348(14): 1333–1341.

- Riello R, Geroldi C, Zanetti O, Frisoni GB. 2002. Caregiver’s distress is associated with delusions in Alzheimer’s patients. Behav Med 28(3): 92–98.

- Robinson DM, Keating GM. 2006. Memantine: a review of its use in Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs 66(11): 1515–1534.

- Robinson KM, Adkisson P, Weinrich S. 2001. Problem behaviour, caregiver reactions, and impact among caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Adv Nurs 36(4): 573–582.

- Shua-Haim JR, Smith JM, Patel SR, et al. 2006. Safety and tolerability of memantine in the treatment of agitation in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot study in community dwelling patients presenting clinical & caregiver impressions. Alzheimers Dement 2(3): 268.