Keywords

Chronic leg ulcers (CLU); Ankle brachial index (ABI); Peripheral arterial disease (PAD)

Introduction

Lower-extremity ulceration does not only affect the patient directly but also has a great impact on the economy since significant healthcare resources are spent to treat, prevent, or decrease the progression of the disease. It decreases the productivity by debilitating the person [1-3]. Foot ulcers are especially common in people who have one or more of the following health problems:

Circulatory problems: Venous / Arterial (PAD)

Risk factors for PAD

Age >70 yrs; Age >50 yrs if atherosclerosis risk (Smoking, Diabetes, Hypertension, Dyslipidemia).

Peripheral neuropathy: Diabetes is the most common cause in middle aged and elderly.

Abnormalities in the bones or muscles of the feet [4-7].

Clinical examination of the lower extremities must be combined with noninvasive or invasive assessment of the circulation to solidify the clinical impression [8,9].

The ankle-brachial index (ABI) is a simple, noninvasive tool used to screen for peripheral arterial disease (PAD), a vascular condition associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Despite its prevalence and cardiovascular risk implications, only 25% of PAD patients are undergoing treatment. As only about 10% of patients with PAD present with classic claudication-40% of patients are asymptomatic-clinicians need to have a high level of suspicion for this disease in their adult patient population [9]. According to American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines, an ABI should be conducted on patients presenting with risk factors for PAD so that therapeutic interventions known to diminish their increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and death may be offered at the right time [8-12].

Major international medical societies recommend calculating the ABI by dividing the highest pressure in the leg by the highest pressure in the arm. PAD severity in each leg is assessed according to the levels of ABI [13-18]:

• 0.91 -1.30: Normal

• 0.70-0.90: Mild occlusion

• 0.40-0.69: Moderate occlusion

• <0.40: Severe occlusion

• >1.30: Poorly compressible vessels.

Mostly this occlusion is due to atheromatous plaques/thrombus in the lumen. Until this obstruction is managed the ulcer would not heal.

The American Diabetes Association recommends measuring ABI in all diabetic patients older than 50 years or in any patient suffering from PAD symptoms or having other CV risk factors [8,9].

Aims and Objectives

The present study was undertaken:

• To study the clinical profile of patients of lower leg and foot ulcers

• To establish the role of ABI in prediction of vascular insufficiency

• To compare the value of ABI in diseased and normal limb

Material and Methods

All the patients with ulcer/ulcers in lower limb below the knee that did not heal within 6 weeks period after onset, presented in plastic surgery OPD at King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, India, between November 2015 to November 2016 were included in the study. In all patients, detail history with reference to onset, duration, complains associated with ulcers and associated systemic diseases were collected. History of previous ulcer noted. A thorough local and systemic examination was carried out. Ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI) was calculated for bilateral (B/L) lower limbs (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Siddique; 40 yrs M with non-healing ulcer Lt great toe (ABI=0.45). Only PTA signals (monophasic flow) were audible on hand held Doppler evaluation.

ABI calculation

Tools needed for measuring ABI

• Sphygmomanometer with appropriately sized cuff(s) for both arm and ankle

• Handheld Doppler device [Huntleigh dopplex model number MD2] with vascular probe

• Conductivity gel compatible with the Doppler device

• Huntleigh healthcare dopplex DR4 software package was used to record velocity/time waveforms of arteries.

Each ankle systolic pressure was divided by the brachial systolic pressure [16,17].

ABI key- abnormal:<0.9 Or >1.3

It was a prospective study involving 50 patients. ABI was calculated for both diseased and normal limb. All observations were tabulated and interpreted in the form of percentage, mean, median and standard deviation. To test the significance of association and difference of means, the Student’s t-test and variance ratio test (F) was applied. All statistical analysis was done with SPSS version: 17.0 statistical package software.

Observation and Results

The mean age of all patients in our study was 47 years. There was one peak in age group, between 36-50 years (44%) and another peak was in patients of age group 51-65 years (28%). This can be due to higher prevalence of vascular etiology of leg ulcers and higher prevalence of diabetic neuropathic ulcers (mean age: 54 years) in elderly age group in our study. Male to female ratio was 6.2:1, showing male predominance (Table 1 and Figure 2).

| |

N |

Range |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

| Age |

50 |

54 |

17 |

71 |

47.16 |

13.897 |

Table 1 Age distribution of patients.

Figure 2: Age distribution of patients.

Chronic leg ulcer with vascular etiology accounted for 84% of all chroniculcers. Maximum ulcers (52%) were due to arterial insufficiency. 24% ulcers were due to venous insufficiency, 8% were mixed (arterial+venous), 10% were neuropathic and in 6% ulcers etiology couldn’t be determined. 62% patients had pain and associated history of claudication and 90% haddischarge in the leg ulcers (Table 2).

| Cause of Ulcer |

N |

% |

| Venous |

12 |

24 |

| Arterial |

26 |

52 |

| Arterial+ Venous |

4 |

8 |

| Neuropathic |

5 |

10 |

| Idiopathic |

3 |

6 |

| Total |

50 |

100 |

Table 2 Distribution of cause of ulcers in patients.

Commonest risk factor associated with chronic leg ulcer patients in our study was smoking (86%). Others were diabetes (30%), anaemia (58%), DM and hypertension both (10%) and hypertension alone in (4%) cases. Mean ulcer size was 43.02 (SD 57.61)sq cm with wide variation among different etiologic groups. Idiopathic ulcers had smallest mean size (5.67 sqcm) and multifactorial ulcer group with the largest mean ulcer size (50.75 sqcm). Clinically absent dorsalis pedis artery (DPA) was strongly associated with low ABI. These patients were having clinical features of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and ischaemic leg ulcers (Table 3).

| |

DPA |

N |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

P Value |

| ABPI Diseased LL |

Present |

32 |

0.9897 |

0.12108 |

0.023* |

| Absent |

18 |

0.8989 |

0.1468 |

Applied unpaired t-test for significance. *significant

Table 3 Mean comparison of ABPI diseased LL with DPA.

Mean value of ABI of diseased (limb with ulcer) limb was 0.96 (max=1.2 and min=0.45) and ABI of normal (limb without ulcer) limb was 0.94 (max=1.2 and min=0.8). The values were almost same. A value of 0.9 indicates possible borderline PAD. A normal ABI value does not absolutely rule out the possibility of PAD. The mean ABI value of recurrent ulcers was 0.85 (< 0.9) suggesting the vascular insufficiency (Table 4).

| |

Recurrent wound |

N |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

P Value |

| ABPI Diseased LL |

Present |

8 |

0.8588 |

0.23259 |

0.025* |

| Absent |

42 |

0.9757 |

0.10421 |

Applied unpaired t-test for significance. *Significant

Table 4 Mean comparison of ABPI diseased LL with recurrence

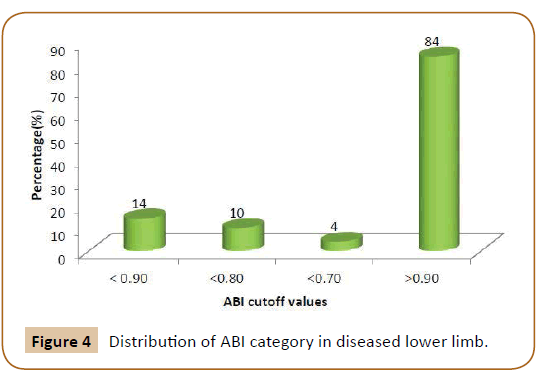

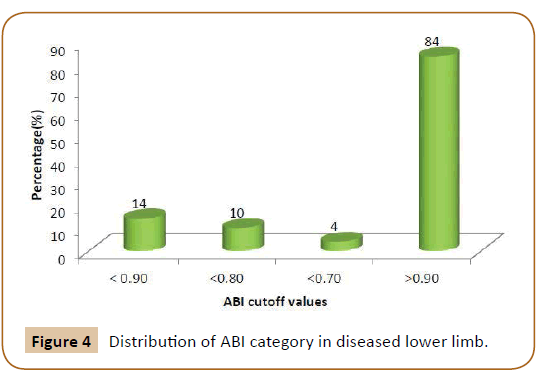

Mean ABI value of diseased limb was 0.94 and it was significantly associated with smoking (former or current smokers);(Pvalue< 0.05). Out of 50 patients; 42 patients (84%) had ABI value>0.90 and 7 patients (14%) had ABI value <0.90 (Table 5).

| |

Tobacco/Smoking (Personal History) |

N |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

P Value |

| ABPI Diseased LL |

Present |

43 |

0.9484 |

0.1402 |

0.027* |

| Absent |

7 |

1.0100 |

0.10599 |

Applied unpaired t-test for significance. *Significant

Table 5 Mean comparison of ABPI diseased LL with smoking status.

Discussion

According to the study conducted by O’Brien et al. [19] in Ireland the prevalence of chronic leg ulcers was 0.12% but it was 1.03% in the patients aged 70 years and over but in our study chronic leg ulcers were more common in patients of age 36-50 years (44%). This can be due to more number of our patients were suffering from Thromboangitis obliterans and strong association was found with tobacco consumption. These were young males belonging to low socioeconomic status. In our study; 86% cases were consuming tobacco either in form of gutka/pan-msala or bidi.

According to the study conducted by O’Brien et al. [19]; Chronic leg ulcers are more prevalent in female than male, same was reported in various other studies in western countries. According to the study conducted by Saraf et al. [20]; a hospital based study in India reported male to female ratio of 5.7:1, which is similar to our institute based study where male to female ratio is 6.2:1, showing male predominance. 88% (44) ulcers were post traumatic and rest 12% (6) were post –infectious. Post traumatic ulcers were more common in males (84%). This may be because in our country males are more engaged in outdoor activities compared to females and they consume more tobacco (panmsala and bidi smoking) as compare to females.

Arterial ulcer is seen among 52% patients in our study. According to GATS-1 (2009-2010) India; prevalence of smoking and any form of tobacco use is more in male (47.9%) compared to female (20.3%) with overall 34.6% tobacco users. Higher rate of smoking and use of tobacco products, especially use of bidi smoking in Indian male could be the cause of more number of male patients compared to female and higher number of arterial ulcers in our study. Also incidence of Burger’s disease (TAO) among peripheral arterial disease is more in India [21-24]. Bidi smoking is prevalent in lower socioeconomic class people who also walk bare foot, so more vulnerable to trauma to foot. Anaemia was present in 58% of cases in our study. Poor education and poverty prevents them to attend health care facility promptly. The above mentioned causes may be the reason of more arterial ulcers in our study.

Venous ulcers are significantly lower in our study (24%) compared to western studies. Only one study available in literature done by Malohotra [25] on prevalence of varicose veins in Indian population, showed prevalence of varicose vein in rail road workers found to be 25.08% in south Indian workers and 6.8% in north Indian workers. No study available comparing duration of ulcer disease between different etiological groups. In our study mean duration of ulcer disease is significantly much greater in ulcers due to neuropathy (22.2 months) followed by ulcers due to arterial + venous disease (21 months).

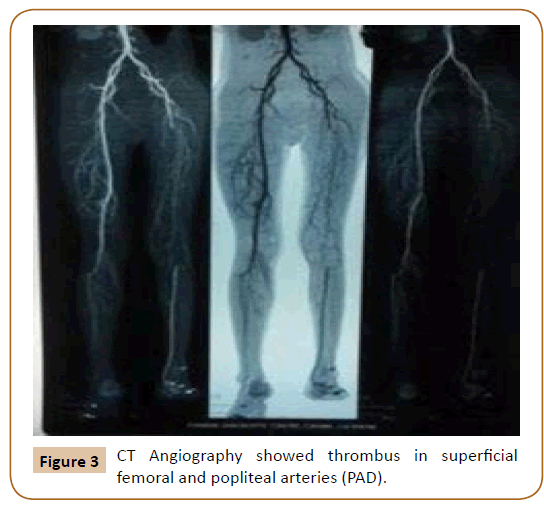

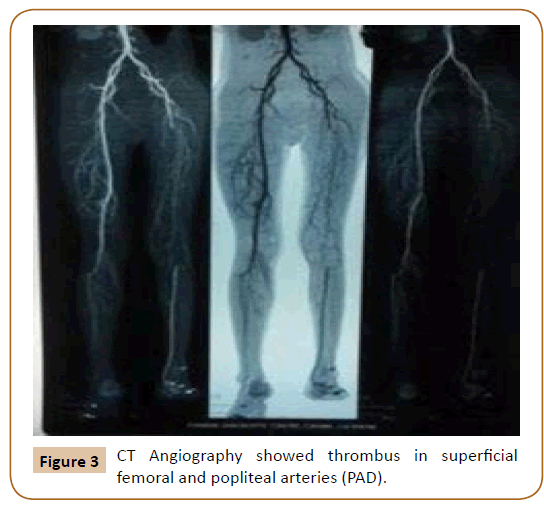

Smoking (86%) is the most common risk factor associated with non healing ulcers in our study group. In our study; smoking is present in almost all patients having ulcer due to arterial diseases. Anaemia, hypoproteinemia and chronic renal disease are commonly seen with CLU due to multifactorial etiologies. Norman et al. [26] concluded that the ankle-brachial pressure index (ABPI) is a simple, non-invasive bedside tool for diagnosing PAD - an ABPI less than 0.9 is considered diagnostic of PAD. In our institute based study, out of 50 patients, DPA was absent in 18 (36%); ATA and PTA were absent in 2 (4%) cases. The mean value of ABI in these 36% patients was 0.898 which is less tan 0.9 and p-value was significant (0.023) means clinically absent DPA is strongly associated with low ABI. These patients were having clinical features of PAD and ischaemic leg ulcers (Figure 3). These results are similar to the other previous studies. An abnormal ABI may be an independent predictor of mortality, as it reflects the burden of atherosclerosis. Majority agree that a normal ABI is >0.9. An ABI <0.9 suggests significant narrowing of one or more blood vessels in the leg [8,9,16]. In our study; mean value of ABI of diseased (limb with ulcer) limb was 0.96 (max=1.2 and min=0.45) and ABI of normal (limb without ulcer) limb was 0.94 (max=1.2 and min=0.8) [27-29]. The values are almost same. 0.9 indicates possible borderline PAD. A normal ABI value does not absolutely rule out the possibility of PAD. The disease (PVD) is generalised; it affects both the lower limbs but the limb with ulcer seeks our attention first. The apparently healthy limb is also at risk of developing ischaemic ulcer. Mean ABI value of diseased limb was 0.94 and it was significantly associated with smoking (former or current smokers); (P-value<0.05). The sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of the ABI as a PAD diagnostic tool is well documented Lijmer et al. (1996) [30-32]; demonstrated a sensitivity of 79 percent and specificity of 96 percent. In our study; out of 50 patients; 42 patients (84%) had ABI value >0.90 and 7 patients (14%) had ABI value <0.90 (Figure 4).

Figure 3: CT Angiography showed thrombus in superficial femoral and popliteal arteries (PAD).

Figure 4: Distribution of ABI category in diseased lower limb.

Out of these 7 (14%); 5 (10%) were having ABI value less than 0.8 and 2 (4%) were having ABI value less than 0.70. ABI less than 0.40 is suggestive of severe PAD. One of our patient was having ABI value 0.45; on further evaluation CT Angiography s/o thrombosis of Lt superficial femoral and popletial arteries and Color Doppler s/o monophasic flow in PTA. Cardio thoracic vascular surgery (CTVS) opinion was taken and patient was planned for PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene) femoropopletial bypass graft to relieve the claudication and ulceration secondary to superficial femoral artery obstruction [33-35].

Conclusion

ABI value less than 0.9 was associated with poor wound healing and more history of recurrence. ABI is a safe and reliable method of monitoring peripheral arterial disease. With the help of ABI, we were able to diagnose vascular insufficiency (PAD) and we managed the patients accordingly. Compression therapy was used in the management of venous ulcers and it was used cautiously in cases of ABI value less than 0.8 to avoid vascular insufficiency. All patients with an ABI of less tan 0.8 should be referred for specialist assessment. In those patients for whom high compression bandaging is contraindicated, reduced compression may be appropriate in selected cases with further arterial investigations if the ulcer fails to respond to treatment.

21788

References

- Elaine F, Leila B, Bernardo H, Marcos MF, Lydia F (2011) Health-related quality of life, self-esteem, and functional status of patients with Leg ulcers. Wounds 23: 4-10.

- Nelzen O, Bergqvist D, Lindhagen A, Hallbook T (1991) Chronic leg ulcers: an underestimated problem in primary health care among elderly patients. J Epidemiol Community Health 45: 184-187.

- Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, Langer RD, Fronek A (1997) The epidemiology of peripheral arterial disease: importance of identifying the population at risk. Vasc Med 2: 221-226.

- Callam MJ, Harper DR, Dale JJ, Ruckley CV (1987) Arterial disease in chronic leg ulceration: an underestimated hazard? Lothian and Forth Valley leg ulcer study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 294: 929-931.

- Shubhangi VA (2013) Chronic Leg Ulcers: Aetiopathogenesis , and Management; Hindawi Publishing Corporation Ulcers. 1-9.

- Powell JT, Edwards RJ, Worrell PC, Franks PJ, Greenhalgh RM, et al. (1997) Risk factors associated with the development of peripheral arterial disease in smokers: a case-control study. Atherosclerosis 129: 41-8.

- Potier L, Abi Khalil C, Mohammedi K, Roussel R (2011) Use and utility of ankle brachial index in patients with diabetes. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 4: 110-116.

- Grasty M (1999) Use of the hand-held Doppler to detect peripheral vascular disease. The Diabet Foot 2: 18-21.

- Kulozik M, Cherry GW, RyanTJ (1986) The importance of measuring the ankle/brachial systolic pressure ratio in the management of leg ulcers. Br J Dermatol115: 26-27.

- Yao J ST (1993) Pressure measurement in the extremity. In: Bernstein, E. F. (ed) Vascular Diagnosis, St Louis: Mosby, 169-175.

- Yao ST, Hobbs JT, Irvine WT (1969) Ankle systolic pressure measurements in arterial disease affecting the lower extremities. Br J Surg 56: 676-679.

- Carter SA (1969) Clinical measurement of systolic pressures in limbs with arterial occlusive disease. Jama 207: 1869 -1874.

- Satomura S (1959) Study of the flow patterns in peripheral arteries by ultrasonics. J Acoust Soc Jap 15: 151

- Strandness DE, Sumner DS (1972) Noninvasive methods of studying peripheral arterial function. J Surg Res 12: 419-430.

- Stubbing NJ, Bailey P, Poole M (1997) Protocol for accurate assessment of ABPI in patients with leg ulcers. J Wound Care 6: 417-418.

- Peter Vowden (2001) Doppler assessment and ABPI: Interpretation in the management of leg ulceration; 2001.

- Carter SA (1985) Role of pressure measurements in vascular disease. In: Bernstein, E. F. (ed) Noninvasive diagnostic techniques in vascular disease, St Louis, Mo.: Mosby, 513-544.

- O' Brien JF, Grace PA, Perry IJ, Burke PE (2000) Prevalence and aetiology of leg ulcers in Ireland. Ir J Med Sci 169: 110–112.

- Saraf SK, Shukla VK, Kaur P, Pandey SS (2000) A clinicoepidemiological profile of non-healing wounds in an Indian hospital. J Wound Care 9: 247-250.

- WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2008: The MPOWER package. Geneva, World Health Organization.

- Global adult tobacco survey [GATS-1] India (2009-2010). Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India.

- Gupta PC, Asma S (2008) Bidi Smoking and Public Health, New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India,145

- Price JF, Mowbray PI, Lee AJ, Rumley A, Lowe GD, et al. (1999) Relationship between smoking and cardiovascular risk factors in the development of peripheral arterial disease and coronary artery disease: Edinburgh Artery Study. Eur Heart J 20: 344-353.

- Malhotra SL (1972) An epidemiological study of varicose veins in Indian rail road workers from the south and north India, with reference to causation and prevention of varicose veins. Int J Epidemiol 1: 177-83.

- Norman PE, Eikelboom JW, Hankey GJ (2004) Peripheral arterial disease: Prognostic significance and prevention of atherothrombotic complications. Med J Aust 181:150-154.

- Lijmer JG, Hunink MG, van den Dungen JJ, Loonstra J, Smit AJ 1996) ROC analysis of noninvasive tests for peripheral arterial disease. Ultrasound Med Biol 22: 391-398.

- Cornwall J. Diagnosis of leg ulcer (1985a) Journal of District Nursing. 4: 4-6.

- Vowden KR, Goulding V, Vowden P (1996a) Hand-held Doppler assessment for peripheral arterial disease. J Wound Care 5: 125-128.

- Georgios S, Nicos L (2009) The evaluation of lower- extremity ulcers; Semin Intervent Radiol 26: 286-295.

- Harriet WH, Cristiane U, Rummana A, Kevin B, Caroline, et al. (2006) Guidelines for the treatment of arterial insufficiency ulcers; Wound Rep Reg 14: 693-710.

- Rahman GA, Adigun IA, Fadeyi A (2010) Epidemiology, etiology, and treatment of chronic leg ulcer: Experience with sixty patients. Afr J Med Sci 9: 1-4.

- Rie RY, Ngoc MP, Makoto O, Takeshi N, Hiromi S, et al. (2014) Comparison of characteristics and healing course of diabetic foot ulcers by etiological classification: Neuropathic, ischemic, and neuro-ischemic type; J Diabetes Complications 28: 528–535

- Shukla VK, Ansari MA, Gupta SK (2005) Wound healing research: A perspective from India. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 4: 7-8.

- Antonio S, Nicolas D, Hannu Sa, Do-DD, Jolanda V, et al. (2006) Falsely high ankle-brachial index predicts major amputation in critical limb ischemia. Vasc Med 11: 69-74.