Keywords

Diabetic kidney disease; Diabetic nephropathy; Prevalence; Risk factors; Nigeria; Meta-analysis

Abbreviations

ACR: Albumin Creatinine Ratio; AJOL: African Journal online; DCCT: Diabetes Control and Complications Trial; DKD: Diabetic Kidney Disease; eGFR: Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate; IDF: International Diabetes Federation; PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; UKPDS: United Kingdome Diabetes Prevention Study

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disorder where reduced insulin secretion or action leads to persistent hyperglycaemia with attendant deleterious effects. It is the most common disease encountered in Endocrinology practice in Nigeria [1,2]. In Subsaharan Africa, Nigeria has the highest number of individuals living with diabetes mellitus [3]. In a meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of diabetes mellitus among adults in Nigeria was 5.77% [4]. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), the prevalence of diabetes mellitus in Nigeria, as at 2020, was 3% although studies have suggested that the burden of the disease in Nigeria was underestimated by IDF because IDF worked with extrapolated data [5]. In terms of hospitalization, about 223 individuals per 100 000 general population get admitted for diabetes and/or its complications yearly in Nigeria, out of which about 22% die [6].

Poorly treated diabetes mellitus is associated with a myriad of micro vascular and macro vascular complications. The most commonly documented micro vascular complications of diabetes mellitus are neuropathy, nephropathy and retinopathy [7].

The rising prevalence of diabetes mellitus, especially type 2, in Nigeria would translate to increasing burden of micro vascular complications and this is quite worrisome as Nigeria is a low resource setting where most patients pay out of pocket [8]. Interestingly, the presence of micro vascular complications independently increases the risk of cardiovascular death in people living with diabetes [9]. This further emphasizes the importance of addressing the micro vascular complications of diabetes mellitus.

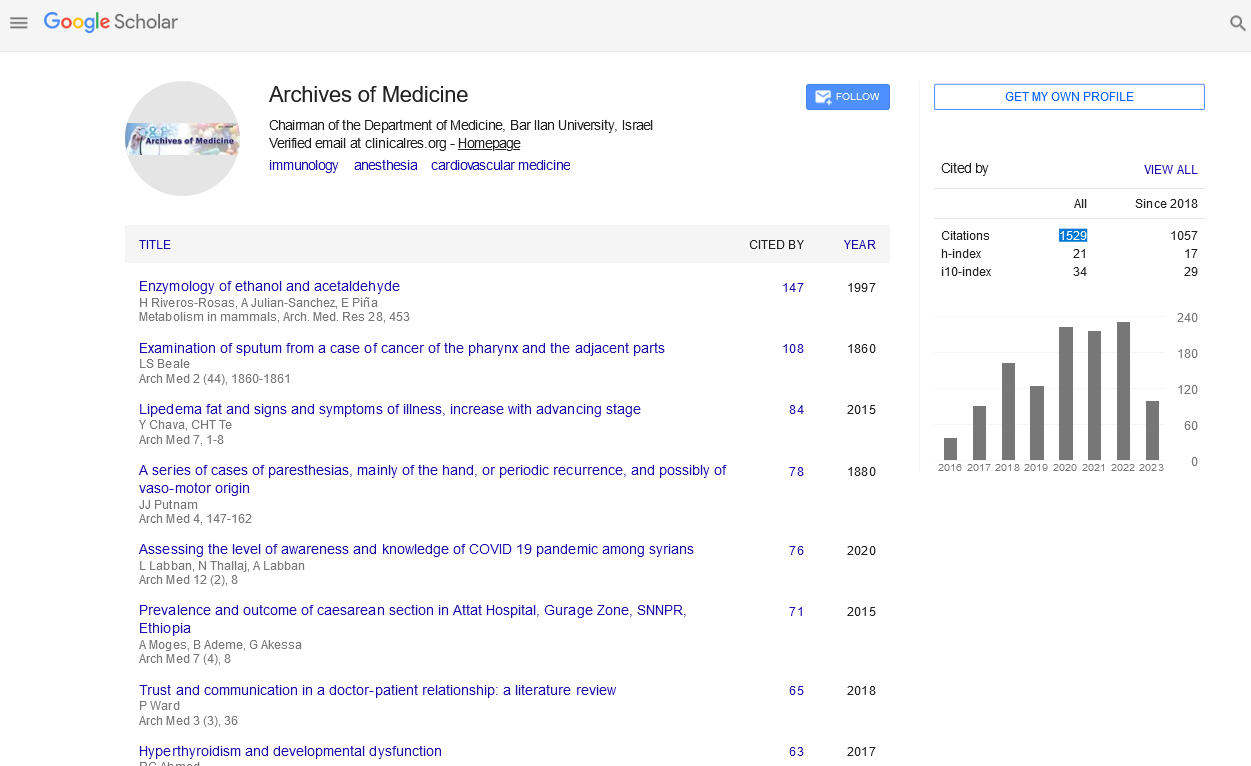

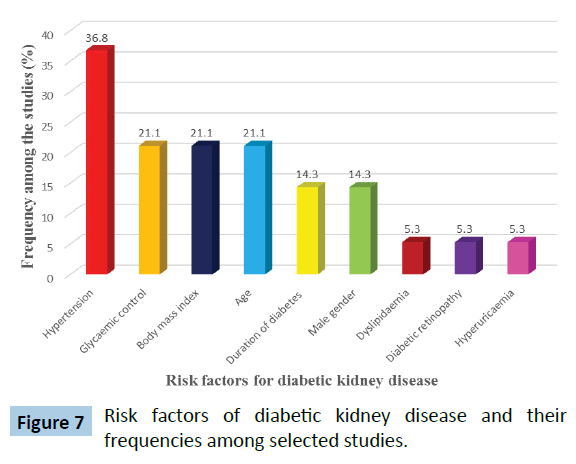

In Nigeria, the third most common cause of chronic kidney disease is diabetes mellitus, after hypertension and chronic glomerulonephritis although diabetes remains the most common cause of end-stage renal disease globally [10,11]. Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD), formerly called diabetic nephropathy, is a complication of diabetes mellitus characterized by persistent albuminuria, confirmed on a second occasion at least 3 months apart and/or progressive deterioration of the estimated glomerular filtration rate [12]. It is of remarkable importance to note that individuals diagnosed with DKD tend to die from cardiovascular diseases and infections even before renal replacement therapy is instituted [12]. The natural history of DKD is shown in Figure 1 below [13].

Figure 1: Natural stages of diabetic kidney disease.

The risk factors for the development of DKD, in addition to sub-optimal glycaemic control, include hypertension, obesity, increasing age, male gender, duration of diabetes, ethnicity and family history [14]. The earliest structural change in DKD on light microscopy is increased mesangial deposition and cellularity, summarily termed as mesangial expansion [15]. Other morphological changes are glomerular basement membrane thickening, microaneurysms, development of the Kimmelstiel- Wilson nodules and hyaline arteriolosclerosis of the afferent and efferent arterioles [12]. However, recent studies have shown that the progression of DKD may not follow any specific pattern suggesting that DKD is a heterogeneous group of disorders rather than a single entity [16]. A study documented that despite declining eGFR, about 40% of the patients never developed albuminuria [12]. The study concluded that albuminuria is a dynamic and fluctuating phenomenon which does not necessarily follow a clearly defined progressive pattern.

The pathophysiology of DKD involves 4 pathways: metabolic, haemodynamic, inflammatory and fibrotic pathways [12]. The metabolic pathway is mediated by increased oxidative stress, formation of advanced glycation end products and increased flux of glucose through the hexosamine pathway generating a higher level of transforming growth factor-β [15]. The haemodynamic pathway is mediated by the activation of the renin-angiotensinaldosterone system, elaboration of nitric oxide and the secretion and activation of endothelins. The inflammatory pathway is due to the increased production of transforming growth factor-α and enhanced synthesis of serum amyloid A. The fibrotic pathway is facilitated by transforming growth factor-β, vascular endothelial growth factor and connective tissue growth factor. The various pathways converge and lead to the various functional, biochemical and structural changes seen in DKD.

Microalbuminuria is defined using 24 hour urinary protein of 30-300 mg or albumin creatinine ratio of 30-300 mg/g in at least two out of three samples taken over 3-6 months [17]. Values above these ranges are termed ’macroalbuminuria’ Screening for microalbuminuria is commenced after the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus or 5-10 years post-diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus and annually thereafter [18]. Diagnosis of diabetic kidney disease is made in the presence of persistent albuminuria (micro- or macro-), presence of diabetic retinopathy and the absence of signs of other forms of renal disease [19]. So, DKD is a diagnosis of exclusion. Management of diabetic kidney disease involves intensive glycaemic control, intensive blood pressure control, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade, dietary modification, treatment of dyslipidaemia and treatment of anaemia. Recently, the use of sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists has been reported to be beneficial in the management of diabetic kidney disease [20-35].

Objective

The objective of the systematic review and meta-analysis was to estimate the pooled prevalence of diabetic kidney disease in Nigeria and identify the risk factors so as to intensify the efforts at preventing and managing the disease.

Literature Review

Relevant articles and papers were searched on the common medical databases. These databases included Google Scholar, PubMed, African Journal online (AJOL) and SCOPUS. The preprint database, medRxiv was also searched. The grey literature was also searched through the helps of the librarian of a university and experts in the relevant fields in Nigeria. This was done to increase the depth of the retrieved articles and minimize publication bias. The search terms were “diabetes mellitus”, “type 2 diabetes”, “type 1 diabetes”, “complications of diabetes”, and “microvascular complications”. Other terms used in the search process were “diabetic kidney disease”, “diabetic nephropathy”, “renal failure”, “Chronic kidney disease”, “end-stage renal disease”, “microalbuminuria”, “macroalbuminuria” and “Nigeria”. The Boolean operators ‘AND’, ‘OR’ as well as ‘NOT’ were used as deemed appropriate to enrich the specificity of the search results.

Abstracts and texts were critically examined by the authors independently. At least three authors agreed on each article that was selected. This was done to minimize the study selection bias. Studies done from 2000 to 2021 were selected. The outcome variables of interest were the prevalence and risk factors for diabetic kidney disease in Nigeria. The data were initially collected on a spread sheet before it was transferred to the meta-analysis software. Meta XL version 5.3 (EpiGear International Ltd.), a meta-analysis add-in software for Microsoft Excel was used for the meta-analysis. The inverse variance heterogeneity model was used for the meta-analysis. Heterogeneity was determined using the I2 statistic and the Cochran’s Q test.

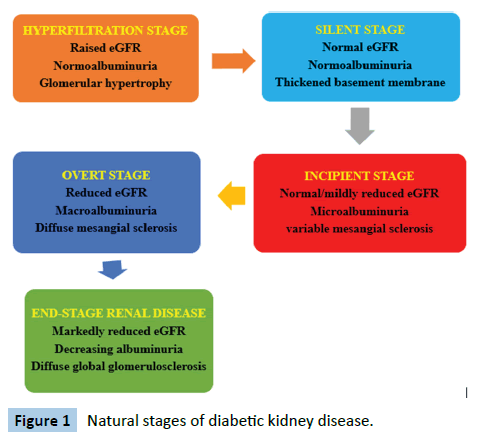

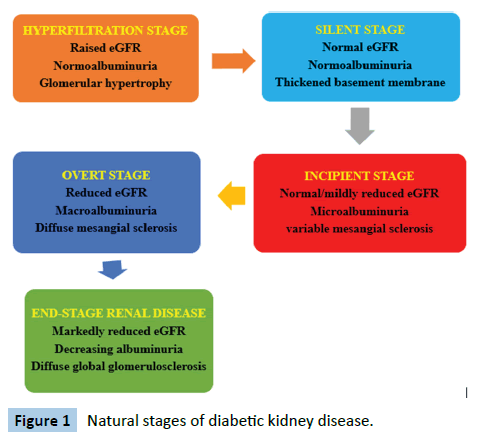

The literature search process and study selection algorithm were done according to the recommended Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The PRISMA flow diagram is shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: The PRISMA flow diagram of the meta-analysis.

Results

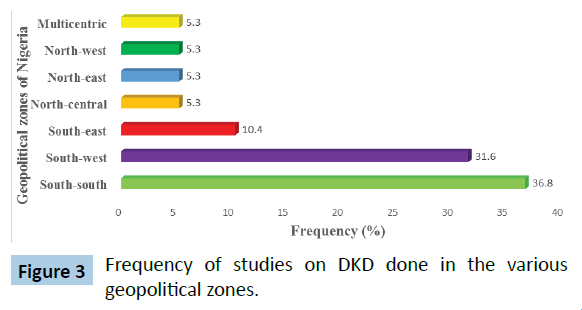

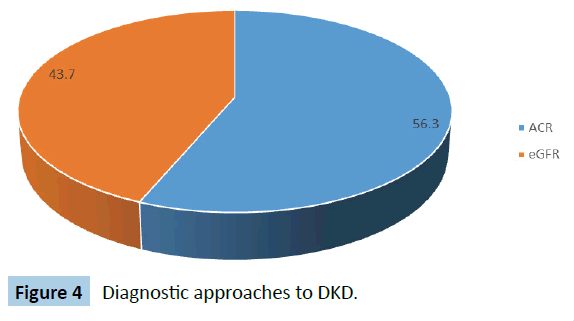

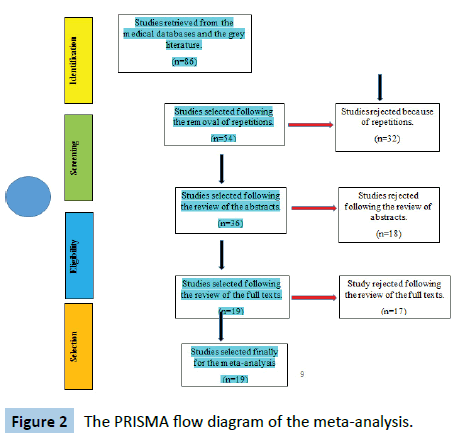

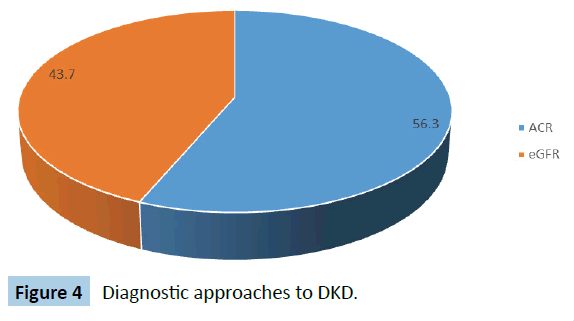

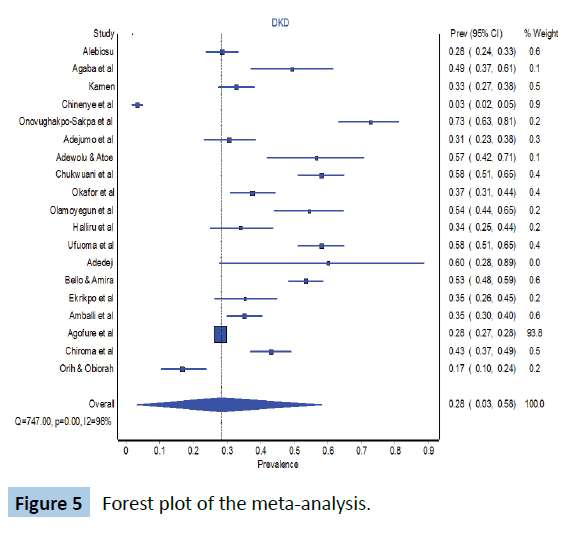

A total of 19 studies met the eligibility criteria and were selected for the meta-analysis. Table 1 shows the selected studies and the prevalence in each study. The total sample size in this metaanalysis was 56 571 individuals with diabetes mellitus. The prevalence of DKD ranges from 3.2% to 72.6% in the selected studies. Figure 3 shows the regional distribution of the studies on the basis of the 6 geopolitical zones of Nigeria. Figure 4 shows the pattern of diagnostic tool for diabetic kidney disease in the various studies. Slightly more studies (56.3%) of the studies adopted the Albumin Creatinine Ratio (ACR) in diagnosing DKD as compared with Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR).

Table 1 Prevalence of diabetic kidney disease in selected studies.

| S. No |

Study |

Year |

Sample size |

Prevalence |

| 1 |

Alebiosu [21] |

2001 |

342 |

28.40% |

| 2 |

Agaba et al [22] |

2004 |

65 |

49.20% |

| 3 |

Kamen [23] |

2007 |

300 |

32.70% |

| 4 |

Chinenye et al. [1] |

2008 |

531 |

3.20% |

| 5 |

Onovughakpo-Sakpa et al. [24] |

2009 |

95 |

72.60% |

| 6 |

Adejumo et al. [10] |

2015 |

144 |

30.60% |

| 7 |

Adewolu & Atoe [25] |

2015 |

46 |

55.60% |

| 8 |

Chukwuani et al [26] |

2015 |

200 |

58.00% |

| 9 |

Okafor et al. [27] |

2015 |

203 |

37.60% |

| 10 |

Olamoyegun et al. [8] |

2015 |

90 |

54.50% |

| 11 |

Halliru et al. [28] |

2016 |

100 |

34.00% |

| 12 |

Ufuoma et al. [29] |

2016 |

200 |

58.00% |

| 13 |

Adedeji [30] |

2017 |

10 |

60.00% |

| 14 |

Bello & Amira [31] |

2017 |

358 |

53.40% |

| 15 |

Ekrikpo et al. [32] |

2017 |

102 |

35.30% |

| 16 |

Amballi et al. [33] |

2018 |

325 |

35.10% |

| 17 |

Agofure et al. [34] |

2020 |

53421 |

27.90% |

| 18 |

Chiroma et al. [35] |

2020 |

261 |

42.90% |

| 19 |

Orih & Obiorah [36] |

2020 |

120 |

16.70% |

Figure 3: Frequency of studies on DKD done in the various geopolitical zones.

Figure 4: Diagnostic approaches to DKD.

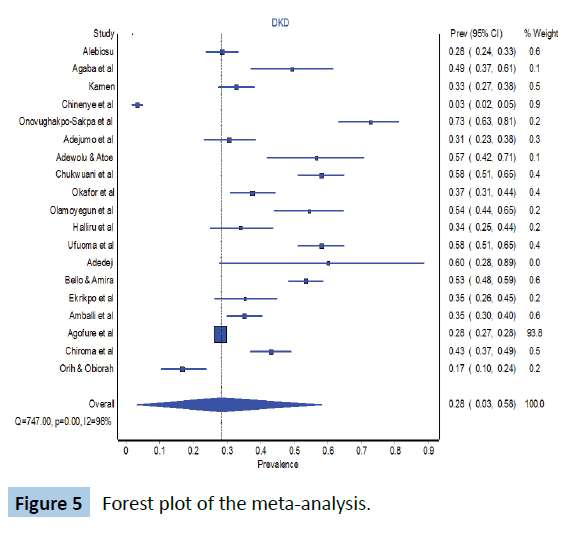

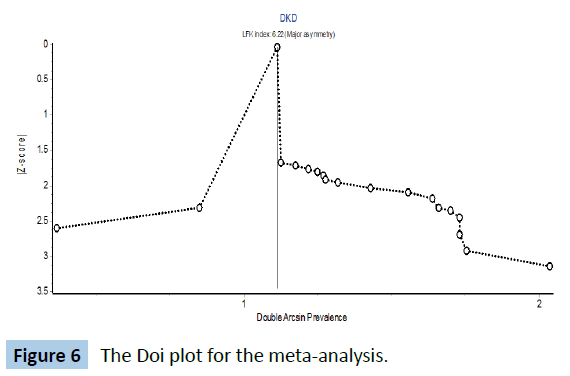

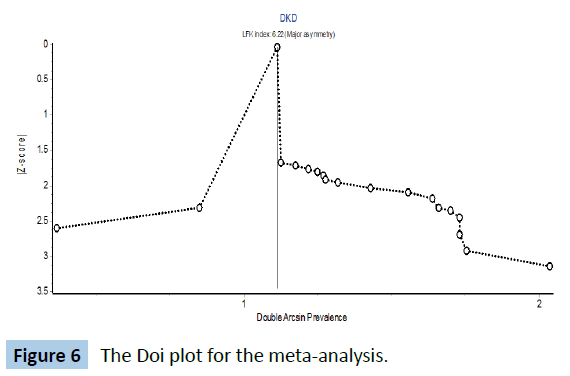

The forest plot is shown in Figure 5 below. The pooled prevalence of diabetic kidney disease in Nigeria is 28% (95% CI 3-58). The Cochran’s Q was 747 (p<0.001) while the I2 statistic was 97.6% and these 2 parameter suggest a high level of heterogeneity in the studies. The Doi plot to check publication bias is shown in Figure 6. LFK index is 6.22 which suggest that there might have been some degree of publication bias.

Figure 5: Forest plot of the meta-analysis.

Figure 6: The Doi plot for the meta-analysis.

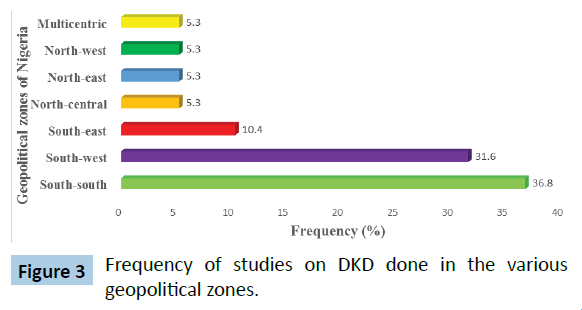

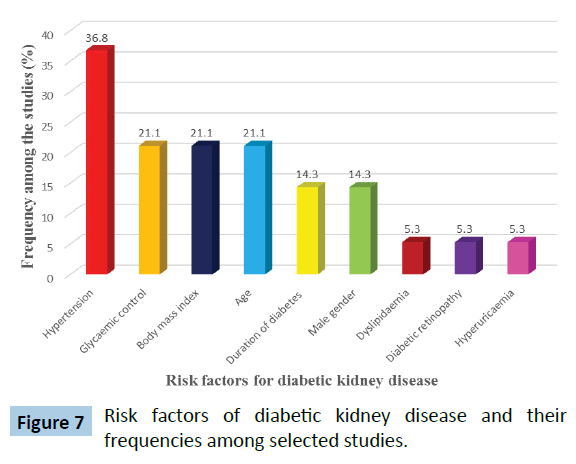

Table 2 shows the risk factors for diabetic kidney disease reported from the selected studies. The frequency of the risk factor in the selected studies is depicted in Figure 7.

Table 2 Risk factors for diabetic kidney disease in Nigeria.

| S. No |

Risk factor |

Studies |

| 1 |

Hypertension |

Olamoyegun et al. [8], Alebiosu [21], Agaba et al. [22], Kamen [23], Ufuoma et al. [29], Adedeji [30], Bello & Amira [31] |

| 2 |

Advancing age |

Olamoyegun et al. [8], Halliru et al. [28], Ufuoma et al. [29], Chiroma et al. [35] |

| 3 |

Sub-optimal glycaemic control |

Olamoyegun et al. [8], Onovughakpo-Sakpa et al. [24], Ufuoma et al. [29], Chiroma et al. [35] |

| 4 |

Increasing body mass index |

Olamoyegun et al. [8], Kamen [23], Ufuoma et al. [29], Ekrikpo et al. [32] |

| 5 |

Duration of diabetes |

Olamoyegun et al. [8], Onovughakpo-Sakpa et al. [24], Adewolu & Atoe [25] |

| 6 |

Male gender |

Olamoyegun et al. [8], Onovughakpo-Sakpa et al. [24], Chiroma et al. [35] |

| 7 |

Dyslipidaemia |

Kamen [23] |

| 8 |

Diabetic retinopathy |

Agaba et al. [22] |

| 9 |

Hyperuricaemia |

Chiroma et al. [35] |

Figure 7: Risk factors of diabetic kidney disease and their frequencies among selected studies.

Discussion

In this meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of diabetic kidney disease in Nigeria was 28%. Previous studies done in other Sub- Saharan Africa countries have found a prevalence rate of 22% - 36% [36-41]. The wide range in the prevalence rate across the continent was also observed in this meta-analysis. This is probably due to the differences in the socio-demographics of the participants, study designs as well as the diagnostic criteria used in the diagnosis of diabetic kidney disease. The tests of heterogeneity (Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistic) earlier mentioned are also in keeping with these observed marked variations in the selected studies. All these are in keeping with the hypothesis that diabetic kidney disease is not a single disease entity but a heterogeneous group of related disorders with a common theme of functional or structural abnormalities of the kidneys in people living with diabetes. This therefore calls for more studies to unravel the various dimensions of the disease.

Most of the selected studies were done in Southern Nigeria. This might raise some questions about the generalizability of the findings of the meta-analysis to the whole nation because regional differences in the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, obesity and other risk factors for diabetic kidney disease had been earlier documented by various authors [4,42,43]. There is a need to conduct appropriately designed studies on the prevalence and risk factors of DKD in the Northern geo-political zones of Nigeria so as to be able to ascertain the burden of the disease in such areas.

This meta-analysis shows that there is lack of consensus in the definition of DKD across the various studies. This may be due to lack of Nigerian guidelines on the diagnosis of diabetic kidney disease and the various authors had to adapt the foreign guidelines. While some studies (43.7%) defined diabetic kidney disease using eGFR, others (56.3%) defined it with albuminuria. There have been controversies on the merits and demerits of each diagnostic criterion and these calls for a national consensus on how to define diabetic kidney disease because the drawbacks of missing patients in the early stage of the disease are quite enormous [44]. A systematic review on diabetic nephropathy in Africa has also identified the same challenge of adopting different criteria in diagnosing DKD [45]. Interestingly, most of the newer guidelines are beginning to incorporate both manifestations (albuminuria and declining eGFR) in the diagnosis and prognosis of DKD [46].

The most commonly reported modifiable risk factors for DKD, in this systematic review, were hypertension, poor glycaemic control and obesity. Various landmark trials such as the United Kingdome Diabetes Prevention Study (UKPDS) and Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) have clearly demonstrated an incontrovertible association between poor glycaemic control and the development of DKD [47]. Additionally, other clinical trials have demonstrated a delay or outright prevention of diabetic kidney disease by ensuring tight glycaemic control. Previous studies done in other continents have also alluded to the relationship between poor glycaemic control and the onset of DKD [48-50].

This review also found out that hypertension was quoted as a major risk factor by various studies on DKD in Nigeria. Previous studies had also reported a similar finding [51,52]. Concerning the association between obesity and the development of DKD, a study in China documented a significant association between body mass index and proteinuria, just as was found in the present meta-analysis [53]. The mechanisms by which obesity exacerbates DKD include insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia, activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and the activation of the sympathetic nervous system [54].

Other risk factors for diabetic kidney disease identified in this meta-analysis were the male gender, age of the patient, duration of diabetes, dyslipidaemia and diabetic neuropathy. These risk factors have also been reported by various authors in their studies [55]. This meta-analysis has highlighted the enormous burden of DKD in Nigeria and it is high time intense efforts were put in place to address these risk factors so as to alleviate the burden of the disease.

Limitations

The studies selected did not cut across all the regions equally due to the dearth of such studies in Northern Nigeria. Similarly, the lack of consensus in the diagnostic criteria limits the generalizability of the findings.

Strengths

The numbers of studies selected were fairly large and the total sample size was also large enough. The meta-analysis spanned about two decades which suggests a wide coverage. This metaanalysis did not only establish the pooled prevalence of DKD in Nigeria but also highlighted the risk factors that need to be focused on so as to mitigate the burden of the disease.

Conclusion

The prevalence of diabetic kidney disease in Nigeria is high. Efforts should be intensified to achieve a tight glycaemic control, optimal blood pressure control, healthy weight as these can go a long way in alleviating the burden of DKD in Nigeria.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable

39103

References

- Chinenye S, Uloko AE, Ogbera AO, Ofoegbu EN, Fasanmade AA, et al. (2012) Profile of Nigerians with diabetes mellitus – Diabcare Nigeria study group (2008): Results of a multicenter study. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 16: 558-564.

- Ale AO, Odusan O (2019) Spectrum of Endocrine Disorders as Seen in a Tertiary Health Facility in Sagamu, Southwest Nigeria. Niger Med J 60:252-256.

- Uloko AE, Musa BM, Ramalan MA, Gezawa ID, Puepet FH, et al. (2018) Prevalence and risk factors for diabetes mellitus in Nigeria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Ther 9: 1307-1316.

- https://idf.org/our-network/regions-members/africa/members/20-nigeria.html

- Adeloye D, Ige JO, Aderemi AV, Adeleye N, Amoo EO, et al. (2017) Estimating the prevalence, hospitalisation and mortality from type 2 diabetes mellitus in Nigeria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 7: e015424.

- Cade WT (2008) Diabetes-related microvascular and macrovascular diseases in the physical therapy setting. Phys Ther 88: 1322-1335.

- Olamoyegun M, Ibraheem W, Iwuala S, Audu M, Kolawole B (2015) Burden and pattern of micro vascular complications in type 2 diabetes in a tertiary health institution in Nigeria. Afr Health Sci 15: 1136-1141.

- Garofolo M, Gualdani E, Giannarelli R, Aragona M, Campi F, et al. (2019) Microvascular complications burden (nephropathy, retinopathy and peripheral polyneuropathy) affects risk of major vascular events and all-cause mortality in type 1 diabetes: A 10-year follow-up study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 18: 159.

- Adejumo OA, Akinbodewa AA, Okaka EI, Alli OE, Ibukun IF (2016) Chronic kidney disease in Nigeria: Late presentation is still the norm. Niger Med J 57: 185.

- Koye DN, Magliano DJ, Nelson RG, Pavkov ME (2018) The Global Epidemiology of Diabetes and Kidney Disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 25: 121-132.

- Alicic RZ, Rooney MT, Tuttle KR (2017) Diabetic kidney disease: Challenges, progress, and possibilities. CJASN 12: 2032-2045.

- Said SM, Nasr SH (2016) Silent diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 90: 24-26.

- Al-Rubeaan K, Youssef AM, Subhani SN, Ahmad NA, Al-Sharqawi AH, et al. (2014) Diabetic Nephropathy and Its Risk Factors in a Society with a Type 2 Diabetes Epidemic: A Saudi National Diabetes Registry-Based Study. PLoS One 9: e88956.

- Alsaad KO, Herzenberg AM (2007) Distinguishing diabetic nephropathy from other causes of glomerulosclerosis: an update. J Clin Pathol 60:18-26.

- Fu H, Liu S, Bastacky SI, Wang X, Tian XJ, et al. (2019) Diabetic kidney diseases revisited: A new perspective for a new era. Mol Metab 30: 250-263.

- McGrath K, Edi R (2019) Diabetic kidney disease: Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. AFP 99: 751-759.

- Chowta NK, Pant P, Chowta MN (2009) Microalbuminuria in diabetes mellitus: Association with age, sex, weight, and creatinine clearance. Indian J Nephrol 19: 53-56.

- Persson F, Rossing P (2018) Diagnosis of diabetic kidney disease: A state of the art and future perspective. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 8: 2-7.

- Nincevic V, Omanovic Kolaric T, Roguljic H, Kizivat T, Smolic M, et al. (2019) Renal benefits of SGLT 2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists: Evidence supporting a paradigm shift in the medical management of type 2 diabetes. Int J Mol Sci 20: 5831.

- Alebiosu CO (2003) Clinical diabetic nephropathy in a tropical African population. West Afr J Med 22: 152-155.

- Agaba E, Agaba P, Puepet F (2004) Prevalence of microalbuminuria in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients in Jos Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci 33: 19-22.

- Adewolu OF, Atoe K (2015) Association between Albumin Creatinine Ratio and e-GFR in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients in Oredo Local Government Area, Benin City, South-South Nigeria. Int J Trop Dis Health pp: 94-101.

- Chukwuani U, Digban KA, Yovwin GD, Chukwuebuni NJ (2016) Prevalence of chronic complications of type 2 diabetes mellitus in a secondary health centre in Niger Delta, Nigeria. Int J Res Med Sci 4: 1080-1085.

- https://www.longdom.org/abstract/audit-of-screening-for-diabetic-nephropathy-in-a-teaching-hospital-in-nigeria-29107.html

- Halliru HA, Musa B, Dahiru SD, Koki YA, Adamu S, et al. (2016) Microalbuminuria as an index of diabetic nephropathy among chronic diabetic patients in Gumel, North Western Nigeria. J Diabetol 7: 3.

- Ufuoma. Prevalence and risk factors of microalbuminuria among type 2 diabetes mellitus: A hospital-based study from, Warri, Nigeria. Sahel Med 19: 16-20.

- Adedeji TA (2017) Renal Function Impairment in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus as determined by Biochemical Markers of Chronic Kidney Disease and Renal Ultrasonography in a Nigerian Tertiary Health Institution: A Preliminary Study. Trop J Nephrol 12: 7-15.

- Bello BT, Amira CO (2017) Pattern and predictors of urine protein excretion among patients with type 2 diabetes attending a single tertiary hospital in Lagos, Nigeria. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 28: 1381.

- Ekrikpo UE, Effa EE, Akpan EE, Obot AS, Kadiri S (2017) Clinical Utility of Urinary ß2-Microglobulin in Detection of Early Nephropathy in African Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Int J Nephrol 2017: e4093171.

- Amballi AA, Odusan O, Ogundahunsi OA, Jaiyesimi AA, Oritogun SK, et al. (2018) Prevalence of microalbuminuria among adults with Type 2 Diabetes mellitus at OOUTH, Sagamu. Ann Health Res 4: 15-21.

- Agofure O, Okandeji-Barry OR, Ogbon P (2020) Pattern of diabetes mellitus complications and co-morbidities in ughelli north local government area, Delta State, Nigeria. Niger J Basic Clin Sci 17: 123-127.

- Orih MC, Obiorah CC (2020) Usefulness of urinary fibronectin and laminin as biomarkers of glomerular injury in diabetics in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. JDE 11: 30-37.

- Wanjohi FW, Otieno FCF, Ogola EN, Amayo EO (2002) Nephropathy in patients with recently diagonised type 2 diabetes mellitus in black Africans. East Afr Med J 79: 399-404.

- Majaliwa ES, Munubhi E, Ramaiya K, Mpembeni R, Sanyiwa A, et al. (2007) Survey on Acute and Chronic Complications in Children and Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes at Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Diabetes Care 30: 2187-2192.

- Pruijm MT, Madeleine G, Riesen WF, Burnier M, Bovet P (2008) Prevalence of microalbuminuria in the general population of Seychelles and strong association with diabetes and hypertension independent of renal markers. J Hypertens 26: 871-877.

- Choukem SP, Dzudie A, Dehayem M, Halle MP, Doualla MS, et al. (2012) Comparison of different blood pressure indices for the prediction of prevalent diabetic nephropathy in a sub-Saharan African population with type 2 diabetes. Pan Afr Med J 11: 67.

- Rasmussen JB, Thomsen JA, Rossing P, Parkinson S, Christensen DL, et al. (2013) Diabetes mellitus, hypertension and albuminuria in rural Zambia: A hospital-based survey. Trop Med Int Health 18: 1080-1084.

- Adeloye D, Ige-Elegbede JO, Ezejimofor M, Owolabi EO, Ezeigwe N, et al. Estimating the prevalence of overweight and obesity in Nigeria in 2020: Asystematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med 53: 495-507.

- Odili AN, Chori BS, Danladi B, Nwakile PC, Okoye IC, et al. (2020) Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment and Control of Hypertension in Nigeria: Data from a Nationwide Survey 2017. Global Heart 15: 47.

- Boer IH de, Steffes MW (2007) Glomerular Filtration Rate and Albuminuria: Twin Manifestations of Nephropathy in Diabetes. JASN 18: 1036-1037.

- Noubiap JJN, Naidoo J, Kengne AP (2015) Diabetic nephropathy in Africa: A systematic review. World J Diabetes 6: 759-773.

- Navaneethan SD, Zoungas S, Caramori ML, Chan JCN, Heerspink HJL, et al. (2021) Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease: Synopsis of the 2020 KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med 174: 385-394.

- Chan GCW, Tang SCW (2016) Diabetic nephropathy: landmark clinical trials and tribulations. Nephrol Dialysis Transpl 31: 359-368.

- Zhang XX, Kong J, Yun K (2020) Prevalence of diabetic nephropathy among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in China: A meta-analysis of observational studies. J Diabetes Res 2020: e2315607.

- Satirapoj B, Adler SG (2015) Prevalence and management of diabetic nephropathy in Western Countries. KDD 1: 61-70.

- Pugliese G, Penno G, Natali A, Barutta F, Di Paolo S, et al. (2020) Diabetic kidney disease: new clinical and therapeutic issues. Joint position statement of the Italian Diabetes Society and the Italian Society of Nephrology on “The natural history of diabetic kidney disease and treatment of hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes and impaired renal function.” J Nephrol. 33: 9-35.

- Harjutsalo V, Groop PH (2014) Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Diabetic Kidney Disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 21: 260-266.

- Wagnew F, Eshetie S, Kibret GD, Zegeye A, Dessie G, et al. (2018) Diabetic nephropathy and hypertension in diabetes patients of sub-Saharan countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Res Notes 11: 565.

- Chen HM, Shen WW, Ge YC, Zhang YD, Xie HL, et al. (2013) The relationship between obesity and diabetic nephropathy in China. BMC Nephrol 14: 69.

- Maric-Bilkan C (2013) Obesity and Diabetic Kidney Disease. Med Clin North Am 97: 59-74.

- Tziomalos K, Athyros VG (2015) Diabetic nephropathy: New risk factors and improvements in diagnosis. Rev Diabet Stud 12: 110-118.