Keywords

Chronic heart failure, Surrogate endpoints, Clinical endpoints, Biomarkers, Serial measurements, Biomarker-guided therapy

Abbrevations

ACC American College of CardiologyACS – acute coronary syndrome, ACEI - angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, ADCHF - acutely decompensated chronic heart failure, AHA - American Heart Association, ANP - atrial natriuretic peptide, ARB - angiotensin receptor blocker, ESC - European Society of Cardiology, CABG - coronary artery bypass grafting, CHF - chronic heart failure;COPD - chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ?V - cardiovascularBNP - brain natriuretic peptide, LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction, MI – myocardial infarction, PCI - Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

INTRODUCTION

Chronic heart failure (CHF) represents the leading cause of cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality worldwide [1]. It has found that CHF occurs in 1%-2% of the adult population in developed countries, and this rate rises to more than 10% in those older 70 years [2].The possibility of timely diagnosis and modern treatment allow significantly improve both short-term and long-term prognosis of this disease [3]. However, expected five-year survival of the patients after a first admission for symptomatic CHF remains low and comparable with cancer, despite all the advances in modern medicine [4]. Even getting of optimal CHF therapy is not guarantee from the occurrence of acutely decompensated CHF, sudden cardiac death, fatal arrhythmias, urgent admission due to CHF or other cardiovascular reasons [5]. Understanding of CHF has progressed from the concept of a purely hemodynamic disorder to that of a syndrome that results from dysfunction in several molecular pathways with mutual interconnections [6]. As a result, the focus of research investigations and clinical care has shifted to measurement and modification of maladaptive molecular processes [7]. In this regard, significant efforts to identify biological markers that reflected several edges of biochemical processes and the risk of clinical outcomes in CHF patients were used [8,9].

Biomarker definition

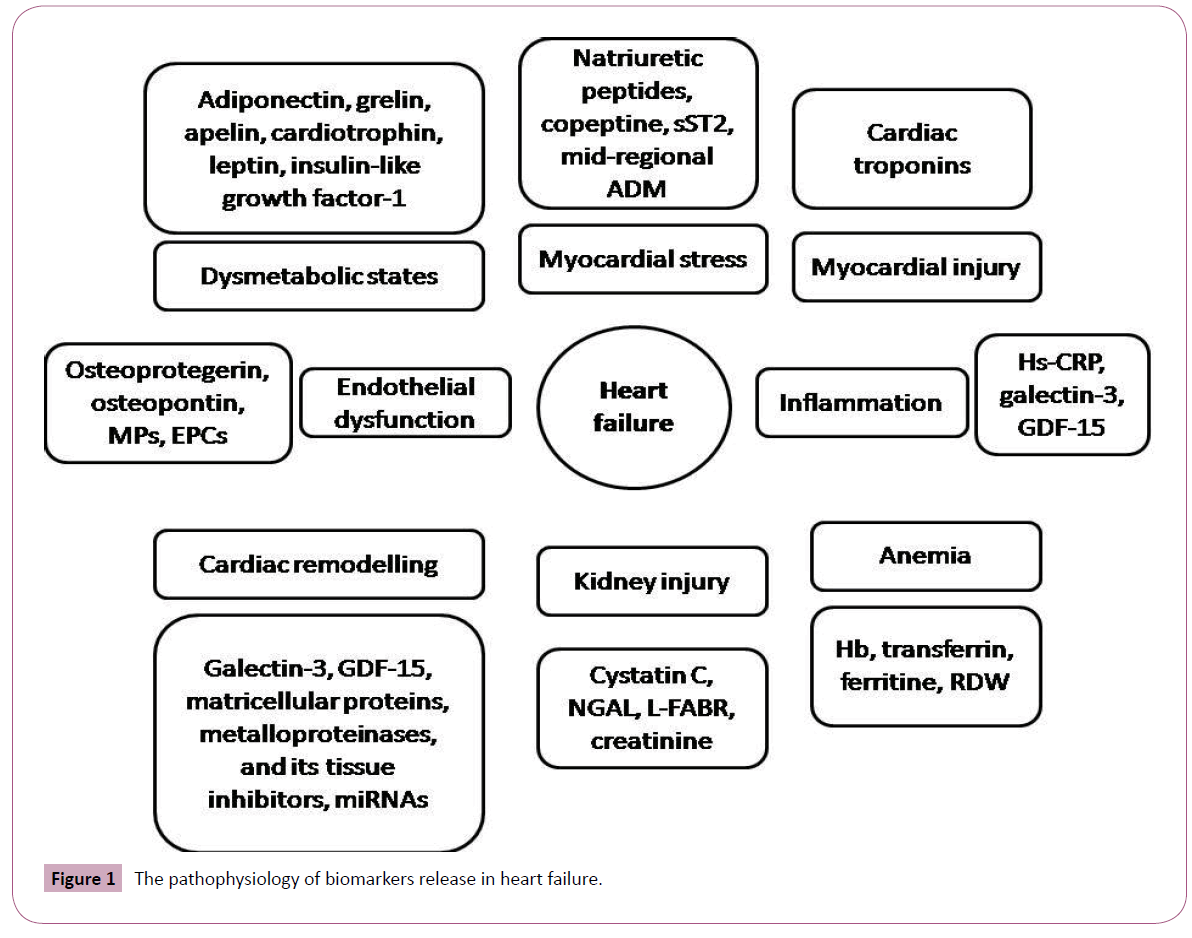

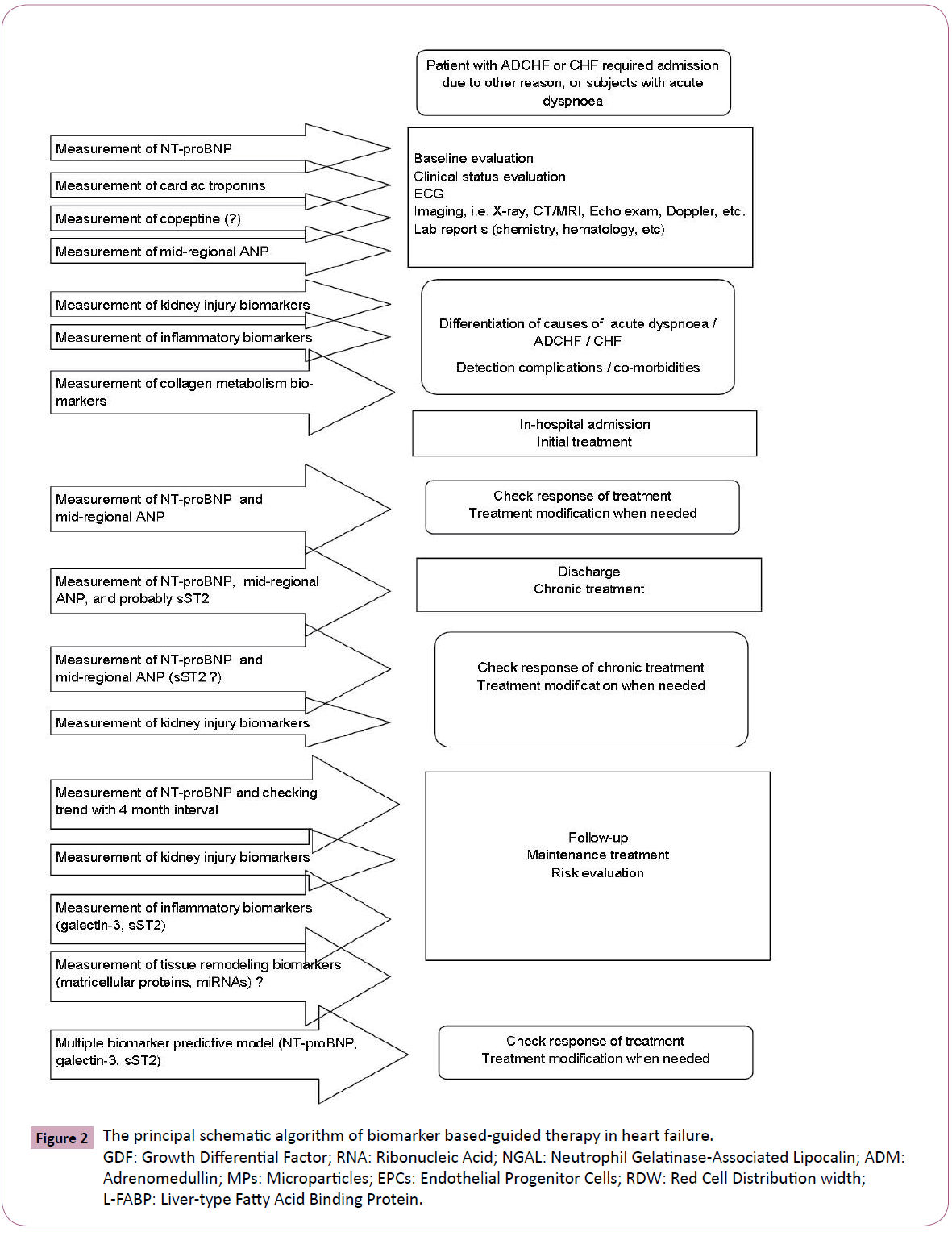

At the current state the biomarkers are defined as objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biologic processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention [10]. Biomarkers may unmask different faces of biological processes, which are contributed several innate mechanisms of pathogenesis in heart failure and mediated of response after treatment or procedures [11,12]. Therefore, some biomarkers are discussed surrogate end-points with high potency to utilization in management for primary-care subjects and patients at discharge after acute or acutely decompensated heart failure [13,14]. Figure 1 illustrates pathophysiology of biomarkers release in heart failure. Overall, there are expectations that ideal biomarker should be precise, accurate, and rapidly available by physician without equivocal and controversial interpretation, produce new or additional important information, that is not surmised from clinical evaluation and may help in decision making, and at last be low cost [15]. Expected requirements for ideal biomarker are given in Table 1

Figure 1: The pathophysiology of biomarkers release in heart failure.

| High sensitive and specific |

| Easy to detect with low biological variation |

| Capable to reflect appropriate molecular interaction, as well as functional, physiological, biochemical processes at the cellular level |

| Capable to indicate acute response after drug given or after injury |

| Quantitatively describing the level of injury by serial measurements |

| Closely correlation with severity of disease and prognosis |

| Predicting progression and target-organ damage |

| Probability of risk stratification for new events and readmission |

| Low cost |

Table 1: Expected requirements for ideal biomarker.

The Natriuretic peptides and heart failure

Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and brain (or B-type) natriuretic peptide (BNP) are neurohormones secreted predominantly from cardiomyocytes in response to a trial or ventricular wall stretch and intracardiac volume loading [16]. The natriuretic peptides have a fundamental role in cardiovascular remodeling, volume homeostasis, and the response to myocardial injury. BNP is considered a counter regulatory hormone to angiotensin II, norepinephrine, and endothelin, having vasodilatorary and diuretic effects [17]. The precursor of BNP is pro-BNP, stored in secretory granules in myocytes. Pro-BNP is split by a protease enzyme into BNP and N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-pro-BNP) [18]. It has investigated that BNP can easily be measured in plasma. It has suggested that the compensatory activity of the cardiac natriuretic peptide system is attenuated as mortality increases in CHF patients with high plasma levels of ANP and BNP [19]. However, BNP and NT-pro-BNP are more useful than ANP for diagnosis and management of acutey decompensated CHF [20]. In this way, it s needed to take attention that elevation of natriuretic peptides may relate to none-cardiac reasons (Table 2).

| Cardiac reasons |

None-cardiac reasons |

| Heart failure (acute, acutely-decompensated, chronic) |

Age more 60 years |

| ACS/ MI |

Anemia |

| Stable CAD |

COPD |

| Ventricular hypertrophy |

Renal failure |

| Cardiomyopathies |

Obstructive sleep apnea |

| Myocarditis |

Pulmonary hypertension |

| Valvular heart diseases |

Pulmonary thromboembolism |

| Pericardial disease |

Pneumonia |

| Atrial fibrillation / flatter |

Injury |

| Cardioversion |

Malignancy |

| Cardiac surgical procedure, including PCI, CABG, and pacemaker implantation |

Critical illness |

| Drug-induced cardiac toxicity (adriamycin, 5-ftoruracil) |

Toxic-metabolic insult |

| |

Sepsis |

| |

Burns |

ACS: acute coronary syndrome

MI: myocardial infarction

PCI: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

CABG: Coronary arteries bypass grafting

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CAD: coronary artery disease

Table 2: The main causes leaded to circulating natriuretic peptide elevation.

Among patients with CHF, concentrations of natriuretic peptides are strongly linked to the presence and severity of structural heart disease and are strongly prognostic in this setting [21,22]. Therefore, it has now shown that an average of BNP and NTproBNP assay results may relate in structure remodeling and biomechanical stress of heart [23]. Because patients with CHF and preserved LVEF have usually smaller LV cavity and thicker LV walls when compared with subjects with reduced LVEF, the intensity of biomechanical stress is also lower [24]. It is needed taking into consideration that patients with preserved LVEF are older and more often female with obese and hypertension than are heart failure patients with reduced LVEF [25-27]. As a result, circulation level of BNP / NT-proBNP is detected in low concentrations than in heart failure subjects with reduced LVEF [28]. Moreover, heart failure patients with preserved LVEF compared with persons without heart failure may have undetected distinguishes in circulating levels of BNP / NT-proBNP [23].

The current guidelines for CHF management indicate that evidence supports the use of natriuretic peptides for the diagnosis, staging, making hospitalization and / or discharge decisions, and identifying patients at risk for clinical events and readmission [29,30]. Because about 50% of individuals with left ventricular systolic dysfunction are asymptomatic, BNP level has been evaluated for this purpose [31,32]. At current time measurement of plasma concentrations of BNP or NT-pro-BNP is useful to rule-out diagnosis and to predict prognosis of patients with ischemic and non-ischaemic CHF, while it remains unclear whether BNP- guided CHF therapy is beneficial and economically feasible [33].

The principles of the natriuretic peptides-guided therapy in chronic heart failure

Standard CHF care has substantial opportunity for improvement outcomes in patients affected by the disorder. Unfortunately, physical signs and symptoms of heart failure lack diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, and medication doses proven to improve mortality in clinical trials are often not achieved [34]. According current expectations, biomarker-guided strategies in heart failure may propose some advantages, which are usually absent in symptom-based treatment approach and echo-based strategy (Table 3).

| Biomarkers |

Target |

Patient populations |

Class ofrecommendation |

Level of evidences |

| Natriuretic peptides |

To establish or refute heart failure |

All patients suspected of having HF, especially when the diagnosis is not certain |

I |

A |

| Predict outcome |

Outpatients with HF |

I |

A |

| Guided-based therapy |

Outpatients with HF |

II a |

B |

| Diagnostic aim |

Inpatients suspected with acute HF |

II b |

C |

| Cardiac specific troponins |

Stratify at risk Predict outcome |

Outpatients with HF Inpatients suspected with acute, acutely decompensated or chronic ischemic HF |

I |

A |

| Galectin-3 |

Stratify at risk Predict outcome |

Outpatients with HF |

II b |

? |

| Inpatients suspected with acute HF |

II b |

? |

HF - Heart failure

Table 3: The 2013 ACC / AHA clinical practice guideline for heart failure: novel issues for biomarkers in heart failure management.

Natriuretic peptide-guided CHF therapy has recently been given a recommendation in USA CHF guidelines to achieve guidelinedirected medical therapy (Class IIa) and possibly improve outcome (Class IIb), while other clinical practice guidelines (including those from the European Society of Cardiology) await results from emerging clinical trial data [29,30]. Experience gained in biomarker-guided CHF trials suggests that the approach results in improvement in the quality of care without an excess of adverse events related to more aggressive management [35,36]. Additionally, favorable reduction in the concentration of BNP and NT-pro-BNP may be seen during treatment of CHF, with parallel improvement in sort- and long-term prognosis. Given these issues, there is increasing interest in harnessing CV biomarkers for clinical application to more effectively guide diagnosis, risk stratification, and further therapy [37]. The evidence for their use in monitoring and adjusting drug therapy is less clearly established [33]. It may be possible to realize an era of personalized medicine for CHF care in which therapy is optimized and costs are controlled and, probably, reduced [7]. However, any positive and negative faces of BNP/NT-proBNP implementation in routine clinical practice should take into consideration (Table 4).

| Positive face |

Negative face |

| More accurate differential diagnosis of acute dyspnea |

High biological variability |

| Reflect the stage and prognosis of HF |

No optimal cut-off points for patients aged more 60 years |

| Easy and reproducibility to detect |

Impossible to differentiate diastolic and systolic types of cardiac dysfunction |

| Ability to be detected by self-measurement |

Underdiagnosed in patients with diastolic dysfunction |

| Low cost |

A drop of 15% and less within 5-7 days of admission due to acute or acutely decompensated heart failure is required an additional consideration about response of the treatment |

HF: Heart failure

BNP: Brain natriuretic peptide

Table 4: Positive and negative faces of BNP/NT-proBNP implementation in routine clinical practice.

Serial measured natriuretic peptide as a useful predictive tool in chronic heart failure management

Recently it has been found that the natriuretic peptides are important tools to establish diagnosis and prognosis in CHF. With application of therapies for CHF, changes in both BNP and NT-pro-BNP parallel the benefits of the CHF therapy might be applied [38]. Among patients admitted with ADCHF, CHF patients who experienced complications were more likely to have much smaller changes (typically 15% decrease) in values of NT-pro-BNP compared to those who survived (about 50% fall in NT-pro-BNP values from day one to seven) [39]. Recently, changes in the BNP level during early aggressive treatment were closely associated with falling pulmonary wedge pressure in patients treated for decompensated CHF [40]. Overall it has been asserted that serial measurements of BNP / NT-pro-BNP could help modulate more accurately the intensity of drug treatment in patients with CHF [41]. Short-term therapeutic studies of inpatients have largely resulted in a statistically significant decline in BNP and NTpro- BNP with clinical evidence of patient improvements [42]. However, it has expected that serial BNP measurements may be useful in evaluating heart failure because there is possibility to overcome biological variability of natriuretic peptide by assessing such measurements.

In contrast, many therapeutic studies involving long-term outpatient monitoring have produced changes in BNP/NT-pro- BNP that do not exceed the biologic variances [42]. Nevertheless, strategy of monitoring NT-pro-BNP and BNP to guide therapy cannot be universally advocated because there are still several open questions about the presumed role of natriuretic peptidesguided pharmacologic adjustment as a valuable strategy in this setting [43,44]. There are data that changes in serial BNP levels during admission of the patients with ADCHF were predictive of clinical outcome. BNP was not compared with other parameters, echocardiographic performances (even such as LVEF), and end points combined in-hospital deaths and post-discharge events [45]. In this study patients had a very high level of BNP and no significant changes of circulating biomarker during admission carte were found. Thus, a probability for drop of BNP/NT-pro- BNP plasma level may associate with severity of heart failure and, probably, coexisting comorbidities. It is well known so called obesity paradox which suggests that the presence of plasma BNP levels in patients with heart failure may be low when obese is presented [46]. When diagnostic utility of biomarkers for heart failure in older subjects in long-term care were examined, it has been found that copeptin (ADM), MR-pro-ADM, and MR-pro- ANP, as well as common signs and symptoms had little diagnostic value in comparison with BNP [47].

However, trend to decreasing BNP/NT-pro-BNP plasma level may be more important fact then peak level of biomarkers. It has found that survivors had lover circulating level of pre-discharged BNP that subjects who were died [48]. In fact, biological variability of BNP/NT-pro-BNP plasma level and closely relation of circulating level of biomarker with age, renal function and comorbidities (such as obesity and diabetes) remains the main limitations for implementation of serial monitoring BNP/NT-pro-BNP in routine clinical practice.

Continued BNP home monitoring in heart failure patients

The hypothesis based on assumption that adding BNP level assay to a home monitoring regimen might add significant value in early detection of heart failure decompensation in stable subjects after discharge was tested in the HABIT Trial (Heart failure Assessment with BNP in the home) [49]. Using appropriate finger-stick test (Alere HeartCheck System) which was specifically designed for home monitoring of BNP levels by heart failure patients, it has been found that upward trend was corresponded to increase a risk of early readmission due to ADHF after discharge. Opposite, downward BNP level trend was indicated a risk decrease. Thus, home monitoring of BNP in stable heart failure patients after discharge may add sufficient information about risk of early readmission within 30 days. Assessment of more durable continued monitoring efficacy is desirable to understand whether novel option is beneficial.

Results of the most important clinical trials devoted BNP-guided therapy

The use of plasma levels of natriuretic peptides to guide treatment of patients with CHF has been investigated in a number of randomized controlled and retrospective clinical trials, however, results of them were closely controversial and the benefits have been high variable. It has found that BNP-guided therapy was not better than expert's clinical assessment for beta-blocker titration in CHF patients [50]. The next study with retrospective design was dedicated the assessment of serial BNP levels in patients receiving hemodynamically guided therapy for severe CHF [51]. It has concluded that in patients with severe heart failure, BNP levels do not accurately predict serial hemodynamic changes including left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and left ventricle dimensions. In the recent Pro-BNP Outpatient Tailored Chronic Heart Failure Therapy (PROTECT) study, patients treated with biomarker-guided care also had improved quality of life and significantly better reverse remodeling on echocardiography compared with patients who received standard care [52]. A multicenter randomized pilot trial STARBRITE was tested whether outpatient diuretic management guided by BNP and clinical assessment resulted in more days alive and not hospitalized over 90 days compared with clinical assessment alone [53]. There was no significant difference in number of day’s alive and not hospitalized, change in serum creatinine, or change in systolic blood pressure. BNP strategy was associated with a trend toward lower blood urea nitrogen; BNP strategy patients received significantly more angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), beta-blockers, and the combination of ACEI or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) plus beta-blockers [53]. However, not all investigators did confirm improving morbidity and mortality in CHF patients by treatment guided by BNP levels, while significantly better clinical outcomes in BNP responders in comparison with non-responders were determined [54].

The long-term prognostic impact of a therapeutic strategy using plasma brain natriuretic peptide levels was evaluated in STARS-BNP Multicenter Study [55]. A total of 220 New York Heart Association functional class II to III patients considered optimally treated with ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, and diuretics by CHF specialists were randomized to medical treatment according to either current guidelines (clinical group) or a goal of decreasing BNP plasma levels <100 pg/ml (BNP group). The primary combined end point was CHFrelated death or hospital stay for CHF. During 15 months follow-up period, significantly fewer patients reached the combined end point in the BNP group [55]. It has noted that the result mentioned above was mainly obtained through an increase in ACEI and beta-blocker dosages adjusted. Later in TIME-CHF trial was found that in contrast to CHF with reduced LVEF, NT-pro-BNP-guided therapy may not be so beneficial in CHF with preserved LVEF [56].

Thus, not always patients won after implementation of BNPguided strategy. However, the heterogeneous result of the natriuretic-peptide guided therapy of CHF is confirmed by several meta-analyses [57,58]. It has found that there was a significantly decreased risk of all-cause mortality and CHF readmission in the BNP-guided therapy group. Age, BNP at baseline are the major dominants of CHF readmission when analyzed using meta-regression. In the subgroup analysis, CHF readmission was significantly decreased in the patients younger than 70 years, or with baseline higher BNP (≥2114 pg/mL). When separately assessment of variables was done, it has found that NT-pro- BNP-guided therapy significantly reduced all-cause mortality and CHF-related hospitalization, but not all-cause admission, whereas BNP-guided therapy did not significantly reduce allcause mortality, CHF-related admission or all-cause admission. It has been concluded that BNP-guided therapy did not significantly reduce both CV mortality and morbidity. On the other hand, improved all-cause mortality and CHF-related admission rate were found in BNP-guided therapy cohorts.

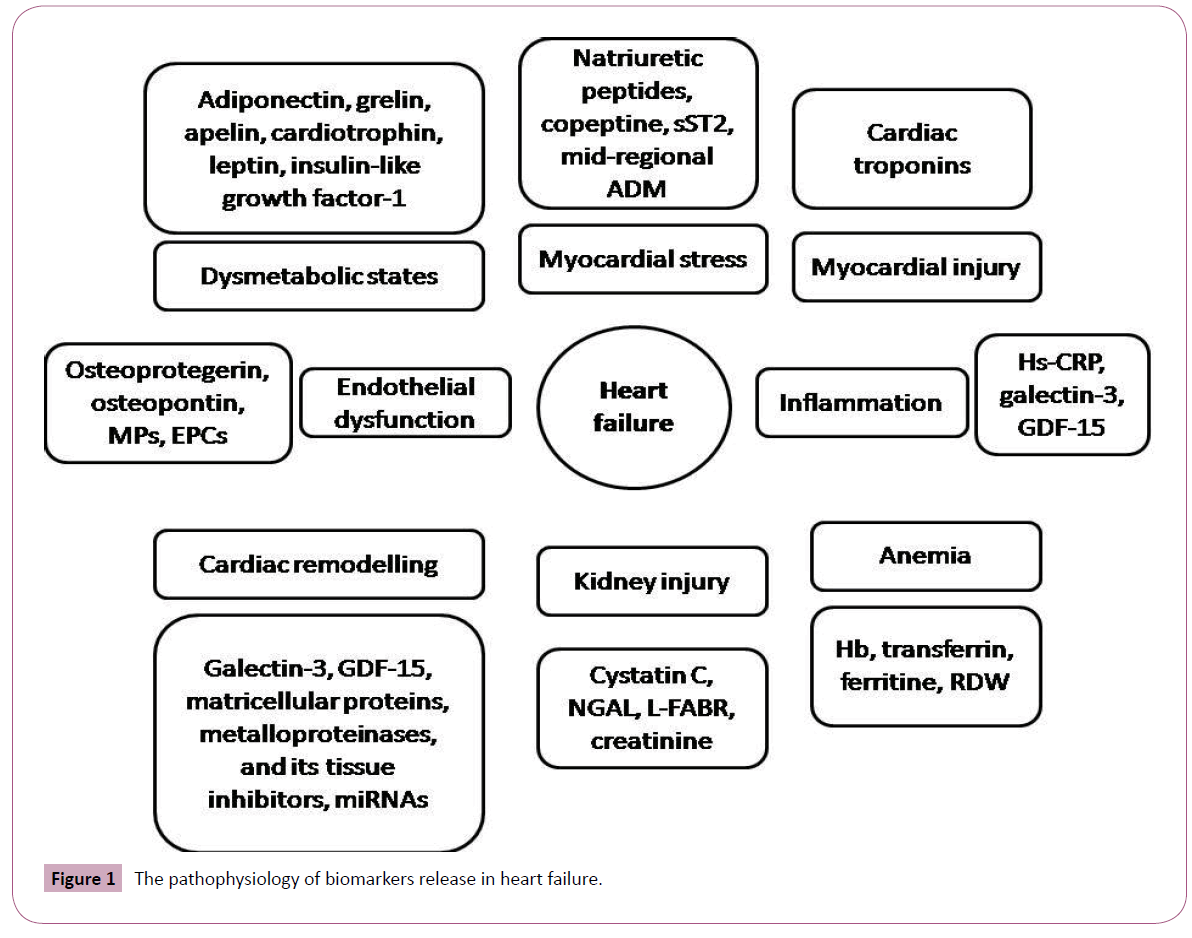

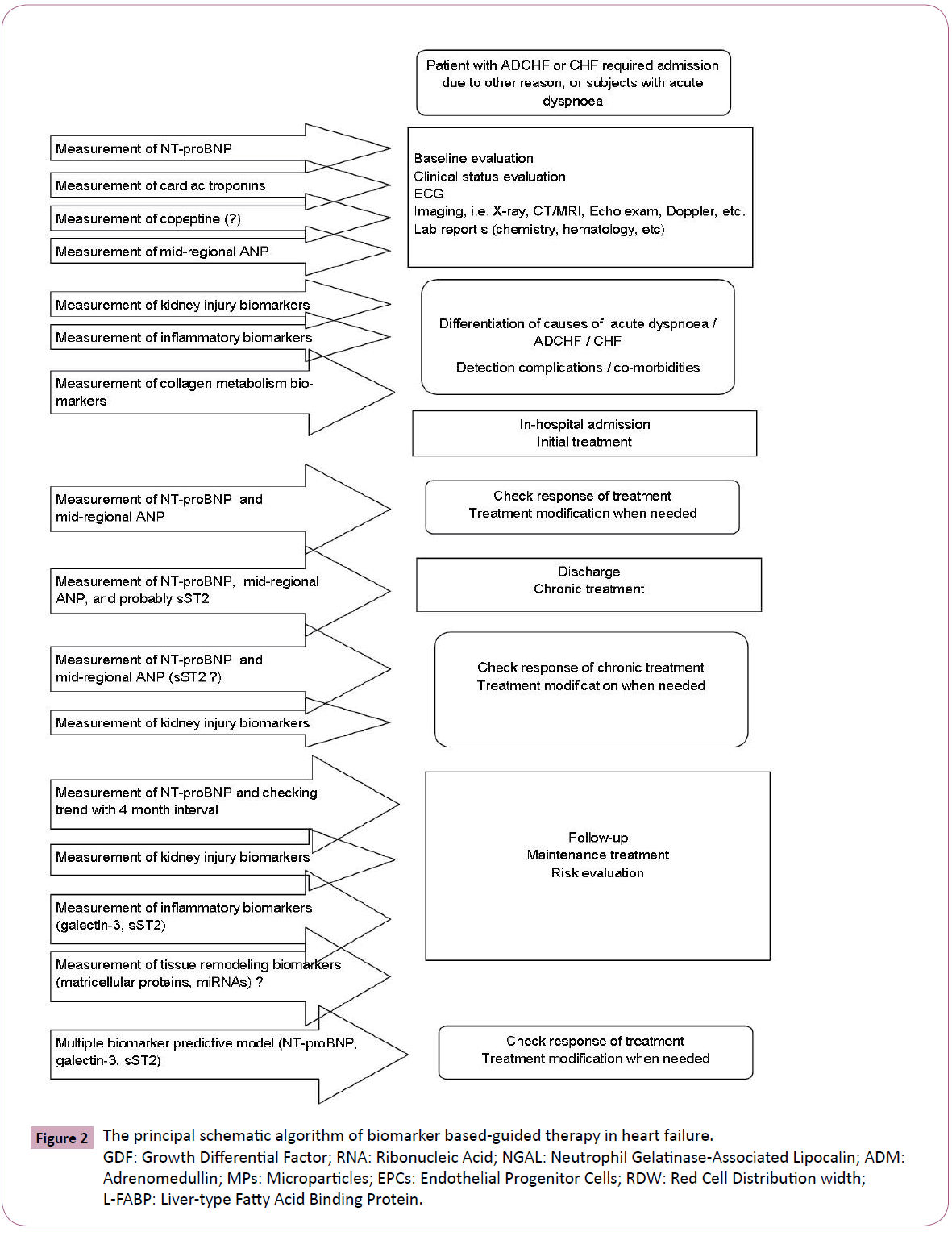

It has been predisposed that changes in follow-up in circulating BNP level instead peak BNP elevation at admission or at discharge is able to stratified CHF patients at risk. The optimal population of these subjects might be in-patient cohort with ADCHF at admission. Overall there are data that reflected existing of closely association between a BNP on the fifth day after admission due to ADCHF and cardiovascular risk. It was found that markedly fall of circulating BNP may be a strong predictor of a decreased risk of the death or new hospitalization, as well as other CHF-related clinical events. On the contrary, recent clinical trials have been shown that BNP-guided therapy in outpatients was associated with a similar risk of death and/or CHF-related hospitalization, compared to the conventional clinical approach [55,59]. Theoretically, the principal schematic algorithm of biomarkers based-guided therapy in heart failure could present follow (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The principal schematic algorithm of biomarker based-guided therapy in heart failure. GDF: Growth Differential Factor; RNA: Ribonucleic Acid; NGAL: Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin; ADM: Adrenomedullin; MPs: Microparticles; EPCs: Endothelial Progenitor Cells; RDW: Red Cell Distribution width; L-FABP: Liver-type Fatty Acid Binding Protein.

It has concluded that among the outpatients with previous ADCTHF, a substantial improvement in cardiovascular event rates could not be demonstrated in those treated with BNP-guided therapy compared with those undergoing usual symptom-guided treatment. The question addressed to inpatients with ADCTHF is still remained unresolved and, probably, required more investigations [59]. On the other hand, some experts believe that novel biomarkers are needed for ADCTHF instead natriuretic peptide, for example: procalcitonin, ST2 protein, mid-regional ANP, galectin-3, copeptin, and probably fibroblast growth factor. However, whether serial measurements of these marker levels to be improved prediction among patients with ADCTHF when compared with traditional approach is still understood.

Cost-effectiveness of natriuretic peptides-guided therapy of CHF

Chronic heart failure management strategies have been shown to reduce re-admissions and mortality, but the costs of treatment may provoke concern in the current cost-conscious clinical settings. Overall, contemporary CHF management programs are under increasing pressure to demonstrate their cost-effectiveness in comparison with other approaches to improving patient outcomes [60-62]. Risk predictive scores, such as The Seattle Heart Failure Model, based on combination of demographic, symptoms and signs of CHF presented, several biomarkers (creatinine, lymphocyte count) significantly predict survival of the subjects with heart failure, as well as produce medical resource use and costs [63]. On-line calculators constructed allow physicians unmask their knowledge around risk and prognosis of the subjects observed [64]. Is implementation of biological markers incorporated into risk scores economic utility effectiveness? Whether creating biomarker risk predictive score is more powerful tool to be stratified the CHF subjects at risk when compared with contemporary predictive models.

Recent studies showed that an introduction of BNP measurement in CHF management may be cost-effective [65,66]. It was found that the optimal use of NT-pro-BNP guidance could reduce the use of echocardiography by up to 58%, prevent 13% of initial hospitalizations, and reduce hospital days by 12% [66]. Moreover, NT-pro-BNP-guided assessment was associated with a 1.6% relative reduction of serious adverse event risk and a 9.4% reduction in costs, translating into savings of $474 per patient, compared with standard clinical assessment. When a new disease management comparing usual care to home-based nurse care and a home-based nurse care group was investigated, it has concluded that NT-pro-BNP-guided CHF specialist care in addition to home-based nurse care was cost effective and cheaper than standard care, whereas home-based nurse care was cost neutral [67]. Thus, BNP-guided CHF therapy may consider high effective strategy to minimize expenditures of health care system for patients with CHF.

Limitations of the natriuretic peptides-guided therapy of CHF

Although the pooling of data derived from the clinical trials demonstrates an overall effect of slightly significant improvement in clinical outcomes with the natriuretic peptide-guided approach, there are some relatively large studies that failed to document a significant clinical improvement in terms of mortality and morbidity using natriuretic peptide-guided strategy [68]. On the one hand, compared with standard management, biomarkerguided care appears cost effective, may improve patient quality of life, and may promote reverse ventricular remodeling. However, there is exist between randomized clinical trials and real-world practice affected implementation of natriuretic peptides guided therapy. On the other hand, the limitation of standard care strategies is evident from the suboptimal uptake and application of proven therapies documented in CHF registries [69]. There are certain subgroups such as the elderly and subjects at low-tomoderate cardiovascular risk that may respond in a less vigorous manner to the approach of natriuretic peptides guided strategy. In certain studies patients treated with biomarker-guided care had superior outcomes when compared with standard heart failure management alone, particularly in younger study populations, in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and particularly when substantial reductions in natriuretic peptides were achieved in association with biomarker-guided care [29]. This may reflect the effects of age on CHF therapy. Therefore, subjects at different cardiovascular risk may distinguish in responses of natriuretic peptides guided therapy. Overall, novel approach, based on biomarker serial measurements, is required serious adaptation in real clinical practice [70].

Novel biomarker-guided approaches in management of CHF

Clinical utilization of cardiac biomarker in heart failure is presented in Table 5. At the current time, galectin-3 and ST2 protein that are reflected fibrosis and inflammation status are approved by FDA as predictive biomarkers for heart failure patients [71]. Unlike BNP / NT-pro-BNP, circulating galectin-3 and soluble ST2 protein concentrations are not affected by obesity, age, atrial fibrillation or the etiology of heart failure [72,73]. Therefore, both biomarkers have also shown significantly less individual variability over a one month time period compared with BNP [72,73]. Although most of the studies involved patients with heart failure and systolic dysfunction, galectin-3 seems to have more accurate role in heart failure patients with preserved LVEF then with reduced LVEF [71]. Results of the PROTECT (ProBNP Outpatient Tailored Chronic Heart Failure Therapy) study have demonstrated that serial measurement of circulating galectin-3 adds incremental prognostic information to conventional predictive score and closely ameliorates prediction value of cardiac remodeling [74]. Unfortunately, no clear effect of contemporary heart failure treatment on galectin-3 levels was found [74]. In the Val-HeFT study baseline galectin-3 was not associated with the risks of all-cause mortality, but increased biomarker level over time in heart failure patients was independently associated with worse outcomes [75]. As in the PROTECT, as well as in the Val-HeFT study, no beneficial effect of serial measurement on outcomes was determined.

| Natriuretic peptides* |

BNP/NT-proBNP, midregionalproBNP, midregionalproANP |

| Cardiac injury biomarkers |

Troponin T*, troponin I*, fatty acid binding protein |

| Metabolic markers |

Adiponectin, grelin, apelin, leptin, insulin-like growth factor-1, cardiotrophin |

| Neurohormones |

Catecholamines, renin, aldosterone, angiotensin, C-terminal pro-vasopressin, mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin, endothelin, urocortin, urotensin |

| Proinflammatory biomarkers |

hs-CRP, galectin-3*, TNF-alpha, ST2 protein*, solubilized ST2 protein receptor, interleukins, Fas (APO-1), myeloperoxidase, |

| Bone-related proteins |

Osteoprotegerin, osteopontin, osteonectin |

| Renal injury biomarkers |

Creatinine, NGAL, cystatin C, KIM-1, L-FABP, cysteine-rich protein |

| Anemia biomarkers |

Hemoglobin, RDW, transferrin, ferritin. |

| Other biomarkers |

Myotrophin, mRNA, growth differential factor-15, collagen peptides, matrix metalloproteinases, tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases, circulating endothelial-derived apoptotic microparticles, circulating mononuclear progenitor cells |

hs-CRP: high sensitive C-reactive protein

mRNA: micro ribonucleic acid

TNF: tumor necrosis factor

APO-1: apoptosis antigen-1

RDW: red cell distribution width

NGAL: neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin

KIM-1: kidney injury molecule-1

L-FABP: liver-type fatty acid binding protein

Notes: * - incorporated in clinical practice guidelines.

Table 5: Clinical Utilization of Cardiac Biomarker in Heart Failure.

Although concentration of sST2 correlates well with BNP levels in heart failure patients, in fact, circulating sST2 levels were not significantly changed according to the degree of renal dysfunction [76,77]. This fact was considered an advantage of sST2 compared with other markers of biomechanical stress (natriuretic peptides), inflammation (galectin-3) and myocardial injury (cardiac specific troponins) in heart failure individuals. It has been postulated that sST2 added to other biomarkers might improve multiple biomarker strategy for risk stratification of death in a real-life HF and increase efficacy of biomarker-guided care based on BNP measurements in combination with established heart failure mortality risk factors (age, sex, left ventricular ejection fraction, New York Heart Association functional class, ischemic heart failure etiology, diabetes, estimated glomerular filtration rate, sodium level, hemoglobin level) [78,79]. Unfortunately, elevation of sST2 in circulation is not specific for HF and has not a powerful diagnostic effect on presentation of cardiac dysfunction unless reduced left ventricular ejection fraction [80,81].

The results of the BACH Study (Biomarkers in ACute Heart Failure) suggested the measurement of three biomarkers (MR-proANP, BNP, and NT-proBNP) allows increasing the predictive value for combination biomarkers, but the role of the approach in guided based therapy remained unclear [82].

Serial measurements of midregion pro-ANP (MR-pro-ANP) and C-terminal provasopressin (copeptin) in ambulatory patients with heart failure were detected as perspective approach for improving prognosis and clinical outcomes [83]. It is well known that MR-pro- ANP and copeptin are precursor peptides of the natriuretic and vasopressin systems respectively. As expected, the strategy based on serial monitoring of MR-pro-ANP and copeptin combined with circulating cardiac troponin T (cTnT), might be advantageous in elucidating and managing the outpatients with heart failure at high risk [84]. The obtained results have been shown that MRpro- ANP, and to a lesser extent copeptin, seemed to add support for an incremental value of serial measurements of BNP and cTnT over time (median = 18.9±7.8 months). Finally, this and other data are indicated that two difference phenotypes of heart failure may be detected using biomarkers: with and without beneficial response after intervention. It is reasonable to believe that perspective of goal biomarker achieving within treatment may reflect as initial severity of heart failure, as well as inadequacy of intervention required dose-adjusted regime or adding new drugs. However, numerous and types of optimal components of biomarker panel for pre-treatment risk stratification and heart failure evolution is remain a big question. All this stimulate new attempts to investigate novel biomarkers, but as it was seen sometimes with negative or equivocal results. Cardiac specific troponins were investigated in studies involved patients with acute ischemic heart failure and ADHF. Both forms of troponins (cTnT and cTnI) have significantly predicted in-hospital mortality in patients after myocardial infarction, but serial measurements of their concentration did not confirm an ability of standard heart failure treatment to improve survival through reducing troponin level [85-87]. However, rapidly rising level of cTnI during admission was associated with worse outcomes when compared with a little or no increased level. Overall, targeting to troponin level is represented as probably, but hardly achieved. Other novel biomarkers, such as fibroblast-growth factors and procalcitonin, are discussed indicator reflected reparation processes, but use of it in guided-based therapy of heart failure is at current time proof-of-concept only. Although procalcitonin looks at this position more attractive, but evidences affected acute dyspnea, acute heart failure and ADHF only [88].

Currently metabolic markers (adiponectin, grelin, apelin, leptin, insulin-like growth factor-1, cardiotrophin), neurohormones (catecholamines, renin, aldosterone, angiotensin, mid regional pro-adrenomedullin), serum bone-related proteins (osteoprotegerin, osteopontin, osteonectin), biomarkers of kidney injury (creatinine, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin [NGAL], cystatin C, KIM-1, L-FABP, cysteine-rich protein), anemia biomarkers (hemoglobin, RDW, transferrin, ferritin), biomarkers of collagen metabolism (growth differential factor-15, collagen peptides, matrix metalloproteinases, tissue inhibitors of matrix), and miRNAs (Table 5) have demonstrated predictive value in heart failure. However, not all of them were incorporated in current clinical guidelines.

The criticism regarding clinical use of these biomarkers appears to be rise because adding these markers into multiple models based on natriuretic peptides and / or galectin-3 did not increase a predictive value of entire model. In this context, some biomarkers that well reflected tissue remodeling (growth differential factor-15, matrix metalloproteinases, tissue inhibitors of matrix), vascular repair (miRNAs), endothelial dysfunction (osteoprotegerin, osteopontin, endothelial-derived microparticles, endothelial progenitor cells), inflammation (ST2), and kidney function (NGAL, cystatin C) are not be useful in diagnostic of heart failure, although they have haven power predictive value. However, the diagnostic role of novel renal biomarkers (NGAL and cystatin C) has not been fully explored specifically in CHF with preserved LVEF. They likely have an impactful role in the assessment and management of acute kidney injury and the cardiorenal syndrome associated with ADCHF or acute heart failure.

Thus, novel biomarkers have shown great promise and stimulated much interest in their validation for ADCHF. However, no data about their surpassing to conventional biomarkers, such as natriuretic peptides, in post discharge patients with CHF. In fact, biomarkers that indicate phenotype of heart failure (ST-2 protein, galectin-3) are probably not suitable for serial monitoring in guided-based therapy. Opposite, natriuretic peptides are more optimal for serial monitoring. It has been postulated that future perspective in biomarker modeling will affect multiple biomarker approach to be stratified patients at risk and re-assayed therapy response.

Conclusion

Recent studies suggested that a strategy of standard-of-care management together with a goal to suppress BNP or NT-pro- BNP concentrations leads to greater application of guidelinederived medical therapy and is well tolerated. Apart from them, a variety of novel (ST-2 protein, galectin-3, copeptin, procalcitonin) or already used (natriuretic peptides) biomarkers, have been tested by small trials for heart failure management, without managing to dominate in every day care. Larger and better randomized clinical trials with high statistical power addressing the unresolved issues of natriuretic peptide-guided therapy in CHF should be provided in the future. However, it might believe that heart failure management will probably involve an algorithm using clinical assessment and a biomarker-guided approach.

6689

References

- Santulli G (2013) Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in the 21st century: updated numbers and updated facts. J CardiovascDesease 1: 1-2.

- Mosterd A, Hoes AW (2007) Clinical epidemiology of heart failure. Heart. 93:1137–1146.

- Komajda M, Lapuerta P, Hermans N, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. (2005) Adherence to guidelines is a predictor of outcome in chronic heart failure: the MAHLER survey. Eur Heart J 26: 1653–1659.

- Stewart S, MacIntyre K, Hole DJ, Capewell S, McMurray JJ (2001) More 'malignant' than cancer? Five-year survival following a first admission for heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 3: 315–322.

- Schou M, Gustafsson F, Videbaek L, Tuxen C, Keller N, et al. (2013) NorthStar Investigators, all members of The Danish Heart Failure Clinics Network. Extended heart failure clinic follow-up in low-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial (NorthStar). Eur Heart J 34: 432-442.

- Liu L, Eisen HJ (2014) Epidemiology of heart failure and scope of the problem.Cardiol. Clin32: 1-8.

- Ahmad T, O'Connor CM (2013) Therapeutic implications of biomarkers in chronic heart failure.ClinPharmacolTher94:468-479.

- Scali MC, Simioniuc A, Dini FL, Marzilli M (2014)The potential value of integrated natriuretic peptide and echo-guided heart failure management. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 12: 27.

- Stienen S, Salah K, Moons AH, Bakx AL, van Pol PE, et al. (2014) Rationale and design of PRIMA II: A multicenter, randomized clinical trial to study the impact of in-hospital guidance for acute decompensated heart failure treatment by a predefined NT-PRoBNP target on the reduction of readmission and Mortality rAtes. Am Heart J 168: 30-36.

- Colburn WA, DeGruttola VG, DeMets DL, Downing GJ, Hoth DF, et al.(2001) Biomarkers Definitions Working Group. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework. ClinPharmacolTher 69: 89–95.

- Vasan RS (2006) Biomarkers of cardiovascular disease: molecular basis and practical considerations. Circulation 113: 2335–2362.

- Wang TJ, Wollert KC, Larson MG, Coglianese E, McCabe EL, et al. (2012) Prognostic utility of novel biomarkers of cardiovascular stress: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 126: 1596-1604.

- Bishu K, Deswal A, Chen HH, LeWinter MM, Lewis GD, et al. (2012) Biomarkers in acutely decompensated heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Am. Heart J 164:763-770.e3.

- Braun E, Landsman K, Zuckerman R, Berger G, Meilik A, et al. (2009) American Heart Association; American College of Cardiology; European Society of Cardiology. Adherence to guidelines improves the clinical outcome of patients with acutely decompensated heart failure. Isr. Med Assoc J 11: 348-353.

- Morrow DA, de Lemos JA (2007) Benchmarks for the assessment of cardiovascular biomarkers. Circulation 115: 949 –952.

- Ancona R, Limongelli G, Pacileo G, Miele T, Rea A, et al. (2007) The role of natriuretic peptides in heart failure. Minerva Med 98: 591-602.

- Tsutamoto T, Horie M (2004) Brain natriuretic peptide. RinshoByori 52: 655-668.

- Chen HH, Burnett JC (2000) Natriuretic peptides in the pathophysiology of congestive heart failure. CurrCardiol Rep 2: 198-205.

- Mant D, Hobbs FR, Glasziou P, Wright L, Hare R, et al. (2008) Identification and guided treatment of ventricular dysfunction in general practice using blood B-type natriuretic peptide. Br J Gen Pract 58: 393-399.

- Worster A, Balion CM, Hill SA, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, et al. (2008) Diagnostic accuracy of BNP and NT-pro-BNP in patients presenting to acute care settings with dyspnea: a systematic review. ClinBiochem41: 250-259.

- Nishikimi T (2012) Clinical significance of BNP as a biomarker for cardiac disease - from a viewpoint of basic science and clinical aspect. Nihon Rinsho 70: 774-784.

- Valle R, Aspromonte N, Giovinazzo P, Carbonieri E, Chiatto M, et al. (2008) B-type natriuretic Peptide-guided treatment for predicting outcome in patients hospitalized in sub-intensive care unit with acute heart failure. J Card Fail 14: 219-224.

- Ohtani T, Mohammed SF, Yamamoto K, Dunlay SM, Weston SA, et al. (2012) Diastolic stiffness as assessed by diastolic wall strain is associated with adverse remodelling and poor outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J 33: 1742-1749.

- Patel HC, Hayward C, di Mario C, Cowie MR, Lyon AR, et al. (2014) Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the impact of stricter definitions. Eur J Heart Fail 16:767-771.

- Lund LH, Donal E, Oger E, Hage C, Persson H, et al. (2014) Association between cardiovascular vs. non-cardiovascular co-morbidities and outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 16: 992-1001.

- Luchner A, Behrens G, Stritzke J, Markus M, Stark K, et al. (2013) Long-term pattern of brain natriuretic peptide and N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide and its determinants in the general population: contribution of age, gender, and cardiac and extra-cardiac factors. Eur J Heart Fail 15: 859-867.

- Mason JM, Hancock HC, Close H, Murphy JJ, Fuat A, et al. (2013) Utility of biomarkers in the differential diagnosis of heart failure in older people: findings from the heart failure in care homes (HFinCH) diagnostic accuracy study. PLoS One 8:e53560.

- Tate S, Griem A, Durbin-Johnson B, Watt C, Schaefer S (2014) Marked elevation of B-type natriuretic peptide in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Biomed Res28: 255-261.

- McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Böhm M, et al. (2012) ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail 14: 803-869.

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, et al. (2013) American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am CollCardiol 62: e147-239.

- Costello-Boerrigter LC, Boerrigter G, Redfield MM, Rodeheffer RJ, Urban LH, et al. (2006) Amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and B-type natriuretic peptide in the general community: determinants and detection of left ventricular dysfunction. J Am CollCardiol 47: 345–353.

- Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Leip EP, et al. (2004) Plasma natriuretic peptide levels and the risk of cardiovascular events and death. N Engl J Med 350: 655–663.

- Vavuranakis M, Kariori MG, Kalogeras KI, Vrachatis DA, Moldovan C, et al. (2012) Biomarkers as a guide of medical treatment in cardiovascular diseases. Curr Med Chem 19: 2485-2496.

- Saremi A, Gopal D, Maisel AS (2012) Brain natriuretic peptide-guided therapy in the inpatient management of decompensated heart failure. Expert Rev CardiovascTher 10: 191-203.

- Samara MA, Tang WH (2011) Device monitoring strategies in acute heart failure syndromes. Heart Fail Rev 16: 491-502.

- Adams KF Jr, Felker GM, Fraij G, Patterson JH, O'Connor CM (2010) Biomarker guided therapy for heart failure: focus on natriuretic peptides. Heart Fail Rev 15: 351-370.

- Fiuzat M, O'Connor CM, Gueyffier F, Mascette AM, Geller NL, et al. (2013) Biomarker-guided therapies in heart failure: a forum for unified strategies. J Card Fail 19: 592-599.

- Troughton R, Michael FG, Januzzi JL Jr (2014) Natriuretic peptide-guided heart failure management. Eur Heart J 35: 16-24.

- Bayes-Genis A, Santalo-Bel M, Zapico-Muniz E, López L, Cotes C, et al. (2004) N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) in the emergency diagnosis and in-hospital monitoring of patients with dyspnoea and ventricular dysfunction. Eur J Heart Fail 6: 301–308.

- Kazanegra R, Cheng V, Garcia A (2001) A rapid test for B-type natriuretic peptide correlates with falling wedge pressures in patients treated for decompensated heart failure. a pilot study. J Card Failure 7: 21-29.

- Januzzi JL, Troughton R (2013) Are serial BNP measurements useful in heart failure management? Serial natriuretic peptide measurements are useful in heart failure management. Circulation. 127: 500-507.

- Wu AH (2006)Serial testing of B-type natriuretic peptide and NT-pro-BNP for monitoring therapy of heart failure: the role of biologic variation in the interpretation of results. Am Heart J152: 828-834.

- De Vecchis R, Esposito C, Di Biase G, Ariano C (2013) B-type natriuretic peptide. Guided vs. conventional care in outpatients with chronic heart failure: a retrospective study. Minerva Cardioangiol 61: 437-449.

- Miller WL, Hartman KA, Burritt MF, Borgeson DD, Burnett JC Jr, et al. (2005) Biomarker responses during and after treatment with nesiritide infusion in patients with decompensated chronic heart failure. ClinChem 51: 569-577.

- Cheng VL, Krishnaswamy P, Kazanegra R (2001) A rapid bedside test for B-type natriuretic peptide predicts treatment outcomes in patients admitted with decompensated heart failure. J Am CollCardiol37: 386-391.

- Adamopoulos C, Meyer P, Desai RV, Karatzidou K, Ovalle F, et al. (2011) Absence of obesity paradox in patients with chronic heart failure and diabetes mellitus: a propensity-matched study. Eur J Heart Fail 13: 200–206.

- Mason JM, Hancock HC, Close H, Murphy JJ, Fuat A, et al. (2013) Utility of biomarkers in the differential diagnosis of heart failure in older people: findings from the heart failure in care homes (HFinCH) diagnostic accuracy study. PLoS One8: e53560.

- Ito K, Kawai M, Nakane T, Narui R, Hioki M, et al. (2012) Serial measurements associated with an amelioration of acute heart failure: an analysis of repeated quantification of plasma BNP levels. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 1:240-247.

- Maisel A, Barnard D, Jaski B, Frivold G, Marais J, et al. (2013) Primary results of the HABIT Trial (heart failure assessment with BNP in the home). J Am CollCardiol 61: 1726-1735.

- Beck-da-Silva L, de Bold A, Fraser M, Williams K, Haddad H. (2005) BNP-guided therapy not better than expert's clinical assessment for beta-blocker titration in patients with heart failure. Congest Heart Fail 11: 248-253.

- O'Neill JO, Bott-Silverman CE, McRae AT, Troughton RW, Ng K, et al. (2005) B-type natriuretic peptide levels are not a surrogate marker for invasive hemodynamics during management of patients with severe heart failure. Am Heart J149: 363-369.

- Januzzi JL (2012) The role of natriuretic peptide testing in guiding chronic heart failure management: review of available data and recommendations for use. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 105:40-50.

- Shah MR, Califf RM, Nohria A, Bhapkar M, Bowers M, et al. (2011) The STARBRITE trial: a randomized, pilot study of B-type natriuretic peptide-guided therapy in patients with advanced heart failure. J Card Fail17: 613-621.

- Karlström P, Alehagen U, Boman K, Dahlström U (2011) UPSTEP-study group. Brain natriuretic peptide-guided treatment does not improve morbidity and mortality in extensively treated patients with chronic heart failure: responders to treatment have a significantly better outcome. Eur J Heart Fail13: 1096-1103.

- Jourdain P, Jondeau G, Funck F, Gueffet P, Le Helloco A, et al. (2007) Plasma brain natriuretic peptide-guided therapy to improve outcome in heart failure: the STARS-BNP Multicenter Study. J Am CollCardiol 49: 1733-1739.

- Maeder MT, Rickenbacher P, Rickli H, Abbühl H, Gutmann M, et al. (2013) TIME-CHF Investigators. N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide-guided management in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: findings from the Trial of Intensified versus standard Medical therapy in Elderly patients with Congestive Heart Failure (TIME-CHF). Eur J Heart Fail15: 1148-1156.

- Savarese G, Trimarco B, Dellegrottaglie S, Prastaro M, Gambardella F, et al. (2013) Natriuretic peptide-guided therapy in chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis of 2,686 patients in 12 randomized trials. PLoS One 8: e58287.

- Li P, Luo Y, Chen YM (2013) B-type natriuretic peptide-guided chronic heart failure therapy: a meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials. Heart Lung Circ 22: 852-860.

- De Vecchis R, Esposito C, Cantatrione S (2013) Natriuretic peptide-guided therapy: further research required for still-unresolved issues. Herz 38: 618-628.

- Turner DA, Paul S, Stone MA, Juarez-Garcia A, Squire I, et al. (2008) Cost-effectiveness of a disease management programme for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and heart failure in primary care. Heart 94: 1601–1606.

- Gonseth J, Guallar-Castillón P, Banegas JR, Rodríguez-Artalejo F (2004) The effectiveness of disease management programmes in reducing hospital re-admission in older patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published reports. Eur Heart J 25:1570–1595.

- Lambrinou E, Kalogirou F, Lamnisos D, Sourtzi P (2012) Effectiveness of heart failure management programmes with nurse-led discharge planning in reducing re-admissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 49:610–624.

- Levy WC, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, Sutradhar SC, Anker SD, et al. (2006) The Seattle Heart Failure Model: prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation. 113: 1424–1433.

- O'Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, Keteyian SJ, Cooper LS, et al. (2009) Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA 301:1439–1450.

- Morimoto T, Hayashino Y, Shimbo T, Izumi T, Fukui T (2004) Is B-type natriuretic peptide-guided heart failure management cost-effective? Int J Cardiol96: 177-181.

- Siebert U, Januzzi JL Jr, Beinfeld MT, Cameron R, Gazelle GS (2006) Cost-effectiveness of using N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide to guide the diagnostic assessment and management of dyspneic patients in the emergency department. Am J Cardiol 98: 800-805.

- Adlbrecht C, Huelsmann M, Berger R, Moertl D, Strunk G, et al. (2011) Cost analysis and cost-effectiveness of NT-proBNP-guided heart failure specialist care in addition to home-based nurse care. Eur J Clin Invest 41: 315-322.

- De Beradinis B, Januzzi JL (2012) Use of biomarkers to guide outpatient therapy of heart failure. CurrOpinCardiol 27: 661-668.

- Komajda M, Lapuerta P, Hermans N, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. (2005) Adherence to guidelines is a predictor of outcome in chronic heart failure: the MAHLER survey. Eur Heart J 26: 1653–1659.

- Wu AH (2013) Biological and analytical variation of clinical biomarker testing: implications for biomarker-guided therapy. Curr Heart Fail Rep 10: 434-440.

- Carrasco-Sánchez FJ, Páez-Rubio MI (2014) Review of the Prognostic Value of Galectin-3 in Heart Failure Focusing on Clinical Utility of Repeated Testing. MolDiagnTher.

- Piper S, Hipperson D, deCourcey J (2014) Biological Variability of Soluble ST2 in Stable Chronic Heart Failure. Heart 100 (Suppl 3): A29.

- Lok DJ, Lok SI, Bruggink-André PW, Badings E, Lipsic E, et al. (2013) Galectin-3 is an independent marker for ventricular remodeling and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Clin Res Cardiol 102: 103-110.

- Motiwala SR, Szymonifka J, Belcher A, Weiner RB, Baggish AL, et al. (2013) Serial measurement of galectin-3 in patients with chronic heart failure: results from the ProBNP Outpatient Tailored Chronic Heart Failure Therapy (PROTECT) study. Eur J Heart Fail 15:1157-1163.

- Anand IS, Rector TS, Kuskowski M, Adourian A, Muntendam P (2013) Baseline and serial measurements of galectin-3 in patients with heart failure: relationship to prognosis and effect of treatment with valsartan in the Val-HeFT. Eur J Heart Fail 15: 511-518.

- Bao YS, Na SP, Zhang P, Jia XB, Liu RC, et al. (2012) Characterization of interleukin-33 and soluble ST2 in serum and their association with disease severity in patients with chronic kidney disease. J ClinImmunol32:587–594.

- Boisot S, Beede J, Isakson S, Chiu A, Clopton P, et al.(2008) Serial sampling of ST2 predicts 90-day mortality following destabilized heart failure. J Card Fail14:732–738.

- Breidthardt T, Balmelli C, Twerenbold R, Mosimann T, Espinola J, et al. (2013) Heart failure therapy-induced early ST2 changes may offer long-term therapy guidance. J Card Fail19:821–828.

- Lupón J, de Antonio M, Galán A, Vila J, Zamora E, et al. (2013) Combined use of the novel biomarkers high-sensitivity troponin T and ST2 for heart failure risk stratification vs conventional assessment. Mayo ClinProc 88:234-243.

- Brunner M, Krenn C, Roth G, Moser B, Dworschak M, et al. (2004) Increased levels of soluble ST2 protein and IgG1 production in patients with sepsis and trauma. Intensive Care Med30:1468–1473.

- Lupón J, Gaggin HK, de Antonio M, Domingo M, Galán A, et al. (2015) Biomarker-assist score for reverse remodeling prediction in heart failure: The ST2-R2 score. Int J Cardiol 184: 337-343.

- Richards M, Di Somma S, Mueller C, Nowak R, Peacock WF, et al. (2013) Atrial fibrillation impairs the diagnostic performance of cardiac natriuretic peptides in dyspneic patients: results from the BACH Study (Biomarkers in ACute Heart Failure). JACC Heart Fail 1: 192-199.

- Miller WL, Hartman KA, Grill DE, Struck J, Bergmann A, et al. (2012) Serial measurements of midregionproANP and copeptin in ambulatory patients with heart failure: incremental prognostic value of novel biomarkers in heart failure. Heart 98: 389-394.

- Xue Y, Clopton P, Peacock WF, Maisel AS (2011) Serial changes in high-sensitive troponin I predict outcome in patients with decompensated heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 13: 37– 42.

- Peacock WF, De Marco T, Fonarow GC, Diercks D, Wynne J, et al. (2008) Cardiac troponin and outcome in acute heart failure. N Engl J Med 358: 2117–2126.

- Fonarow GC, Peacock WF, Horwich TB, Phillips CO, Givertz MM, et al. (2008) Usefulness of B-type natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin levels to predict in-hospital mortality from ADHERE. Am J Cardiol 101: 231–237.

- Travaglino F, Russo V, De Berardinis B, Numeroso F, Catania P, et al. (2014) Thirty and ninety days mortality predictive value of admission and in-hospital procalcitonin and mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin testing in patients with dyspnea. Results from the VERyfingDYspnea trial. Am J Emerg Med 32: 334-341.

- Naffaa M, Makhoul BF, Tobia A, Jarous M, Kaplan M, et al. (2014) Brain natriuretic peptide at discharge as a predictor of 6-month mortality in acute decompensated heart failure. Am J Emerg Med 32: 44-49.