Keywords

women, domestic violence, Crete, Greece.

Introduction

The phenomenon of violence against women was not a popular topic in the wider public health discourse until the 1970’s, where in the US and other Western countries with the resurgence of the feminist movement women started to discuss about their experiences more openly, thus revealing its frequency and importance to the victims’ lives [1]. Moreover, literature suggests that the role of health professionals in the timely identification of victims as well as their contribution in dealing with the problem prove to be of critical importance [2].

The World Health Organization defines violence as “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment or deprivation [2]. The WHO 2007 Report distinguishes violence in distinct typologies: physical, psychological, sexual and neglect and deprivation. Also, there is a distinction between violence coming from the community or from the family [3].

Violence, whether it be intrafamilial or not, proves to be a serious threat for the victim herself, her children and unborn babies. Violence is one of the main causes of death and injury to women worldwide, independently of the level of development of each country. Moreover, WHO supports that domestic violence is independent of social, economic, religious or cultural background of both the culprit and the victim [2].

The effects of domestic violence may be immediate and direct, such as injury or death, long-term and direct, such as disability, or indirect, such as gastroenterological problems or any combination of the previous. Some of the symptoms that are related to domestic violence are gastrointestinal problems, pelvic pains, stress, depression and hysteria [4,5]. It is also noteworthy that domestic violence often leads to the murder of the victim. In the US in the period from 1976 to 1996, 30% of female murders were committed by their partners or husbands. If one also considers that in 28% of the cases the murderer was not identified, then within the murders with a known murderer, 41% were committed by a partner or husband [6], which proves that the contribution of doctors and other medical staff in the timely identification of such cases and taking relevant action can be a matter of life or death for the victim. Moreover, victims are more likely to abuse alcohol or other substances [7] and to suffer from complexities during pregnancy, a fact which often brings them to health centers, where the medical staff or doctor may be able to detect signs of domestic violence [8]. If one considers the negative impact of the above on the victim’s physical and psychological health, it becomes clear that domestic violence may also negatively affect the victim’s professional and social life [3]. The effects of domestic violence prove to have very important consequences to public health in general, as well as to the morbidity and mortality rates of the victims. In general terms, the phenomenon seems to be on an increase around the world in the last decades according to studies conducted by the WHO [2].

Health professionals can play a key role in tackling the phenomenon of violence against women, if they have had relevant education and information and if the work environment, as well as the institutional factors can support their participation [9]. The timely and successful intervention of health professionals, except for the obvious benefits to the victim and its family (the provision of health services targeted to the direct consequences of an assault, such as taking care of the victims’ injuries) may have enormous benefits for public health and contribute in significant cost-saving. In the US the cost of intimate partner violence has been calculated to a staggering 4 billion dollars according to the American National Center for Injury Prevention and Control [10].

Violence against women is a global phenomenon which is becoming all the more frequent in every part of the world and is not particularly related to any sociological conditions or other exogenous variables. According to a WHO report which draws information from 48 epidemiological studies in the world supports that 10% to 69% of women have experienced abuse from their violent partner at least once in their lives [2].

According to the Greek Center of Gender Equality Studies between 48,3% and 61.9% of women have been the victims of physical or verbal abuse in Greece [11]. The rates differ even within a country because of the lack of a clear definition of violence, as well as due to the fact that different agencies are called to record such cases without always having any training. Notwithstanding the high frequency of the phenomenon and the fact that specific symptoms are associated with domestic violence, a small fraction of cases is identified by doctors or recorded as such [12].

The objective of this study was to identify the attitudes of health professionals towards the victims of domestic violence. To this end, they were asked if and with which frequency they would ask women exhibiting the main symptoms associated with domestic violence in literature, whether they had been victims of domestic violence. Moreover, they were also asked whether they would take any action and which factors could hinder their intervention, thus detecting their attitude towards the phenomenon within the boundaries of their professional role. This need for this research is reinforced by the fact that most women who have been victims of domestic violence fail to be identified as such by the authorities [13].

Methodology

The research was conducted with the use of a structured questionnaire. The sample consisted of 484 health care professionals working in primary and secondary care units in all four prefectures of the island of Crete. The sampling method used for this study was convenience sampling.

The questions developed for this research were based on existing studies and questionnaires [14-19]. The questionnaire consisted of seven questions in the first part that dealt with the treatment of patients, thus examining the attitudes of health professionals towards the phenomenon of domestic violence as well as their perception of it. The second part dealt with the demographic data of the participants.

In the first part of the questionnaire closed, structured questions were used in order to allow the accurate classification of answers. Health professionals were asked to assess the contribution of domestic violence towards specific health symptoms. Moreover, they were asked for their opinion regarding the frequency and size of the phenomenon, based on their experience. The next two questions attempted to detect their treatment of a victim of domestic violence, thus presenting the practices that are followed in such cases by health care professionals. The last three questions were targeted towards the attitudes of health care professionals towards the phenomenon of domestic violence and focus on their perception of their role in detecting and providing health care services to victims, as well as the obstacles they face while dealing with such cases.

In the second part the questions were closed and aimed at recording the demographic data of the participants. The participants were asked for the hospital or health centre in which they work, their profession and education level. Finally, they were also asked for their age, years of experience and specific work area. The last two questions asked whether the participant has taken a course as part of their formal education or in seminars regarding domestic violence. The data was analyzed with the use of SPSS V. 16.

Results

Demographical Data

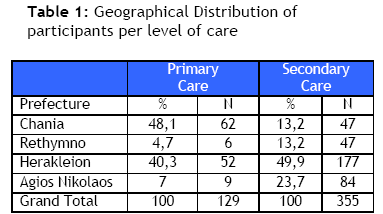

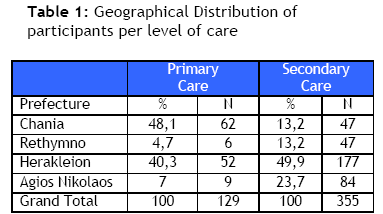

The final sample of the study was 129 health professionals in primary (health centers) and 355 in secondary health care units (hospitals) from all four prefectures of Crete. The geographical distribution per level of care of the sample is presented in Table 1.

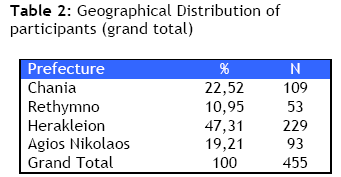

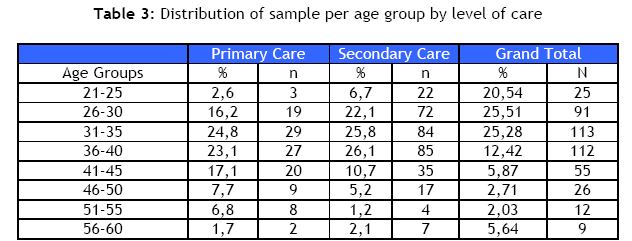

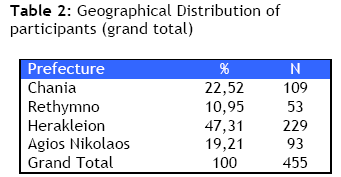

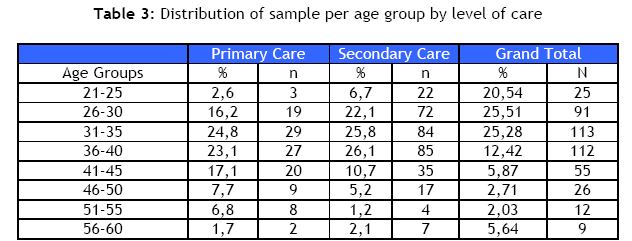

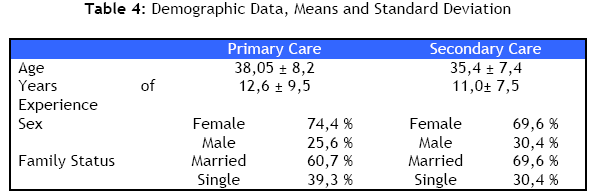

From the above tables it becomes clear that the largest number of questionnaires came from Herakleion (47.31% of total), which is mainly driven by the number of participants in secondary care (49,9%). The next table depicts the age distribution of the sample. From the table becomes clear that the sample consists mainly of younger health professionals, from 21 to 45 years of age (80.72%), with the age groups 26-30, 31-35, 36-40 and 41-45 exhibiting the largest numbers of participants.

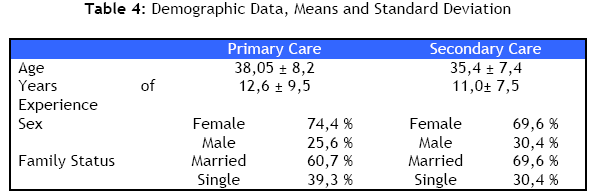

From the analysis of the sample, 12.1% (16) of participants of health professionals in primary care had participated in a seminar, relevant to domestic violence, while in secondary care the number drops to 5.9% (21 participants). 10.5 % of health professionals in primary care (16) had a relevant course in their studies, whereas 7,6 % (28) of health professionals in secondary care. It becomes clear from the above that health professionals in primary care have had better training with regard to domestic violence whether in seminars or within the scope of their studies. In primary care 3,5% (5) of employees has a postgraduate qualification, while the number falls to 1.7% (6) in secondary care. This trend is reversed when it comes to doctorates, where 1,6% (2) of health professionals in primary care possessed a doctorate and 2,3% (8) in secondary care, although both rates are very low.

Topic-Related Questions

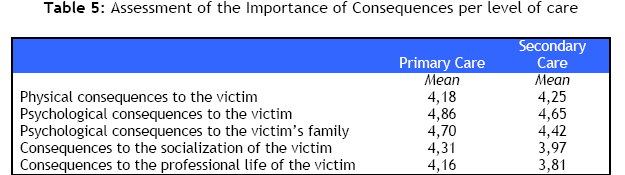

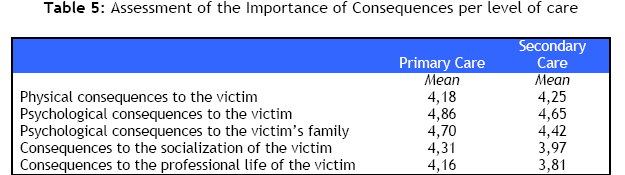

In this part of the questionnaire, health professionals were asked if they detect and how they rate specific consequences of domestic violence. The consequences which are included in the questionnaire are closely associated with domestic violence in literature and are depicted in Table 5. This facilitated the assessment of the level of knowledge of health professionals as regards domestic violence. In the table below, as well as in all the remaining tables, health professionals in both levels of care were asked to rate with 1 for least importance to 5 for most importance.

The psychological consequences to the victim were rated as the most important followed by the psychological consequences to the victim’s family by health professionals in both primary and secondary care. As far as the consequences to the victim’s physical health are concerned, 45,7% of health professionals in primary and 52,1% in secondary care did not view them as important, while for socialization the percentages are 50,4% and 39,9% and for professional life 40,3% and 33,9% respectively. Therefore, health professionals seem to focus on the psychological consequences to the victim and its family.

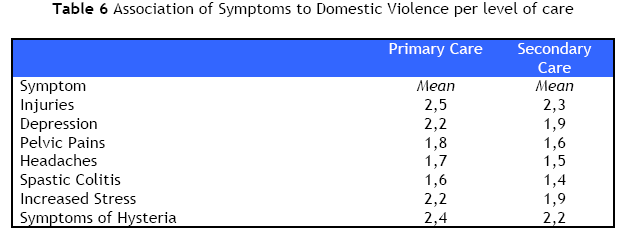

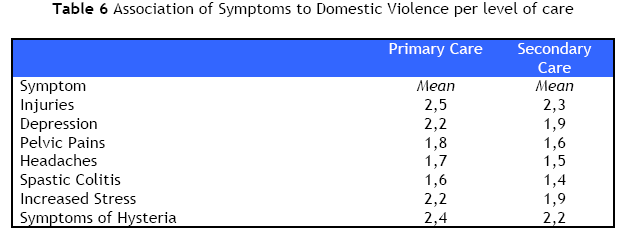

From the data analysis, it becomes clear that health professionals did not regard the following symptoms as frequent consequences of domestic violence: pelvic pains, headache, spastic colitis, and as a consequence would not ask frequently if the patient had been subject to domestic violence. The next questions dealt with the treatment of victims by health professionals. A large number of health professionals in secondary care (40,6%) would ask their patients if they had been subject to domestic violence if they saw injuries on their bodies, while health professionals in secondary care appeared to be more sensitized as an increased number of health professionals would pose the question (56.6%). For symptoms of hysteria 50,2% of health professionals in primary care would always ask, while in secondary care 44,9% would pose the same question.

Similar were the differences between health professionals in the two levels of care in the remaining questions: 49,6% of health professionals in primary care would ask sometimes if the patient was a victim of domestic violence in case of indication or symptoms of spastic colitis, while 55,5% in case of pelvic pain, 48% for headache, and finally, for depression the figure rose to 60%. For health professionals in secondary care the figures were lower. Specifically, 53.8% would ask sometimes 53,8% in case of depression (versus 60% in primary care), 50,8% for excess stress. Contrarily, a large number would never ask if a patient was victim of domestic violence in case of indication or symptoms of pelvic pain (51,4%), headaches (56,7%) or spastic colitis (60,1%).

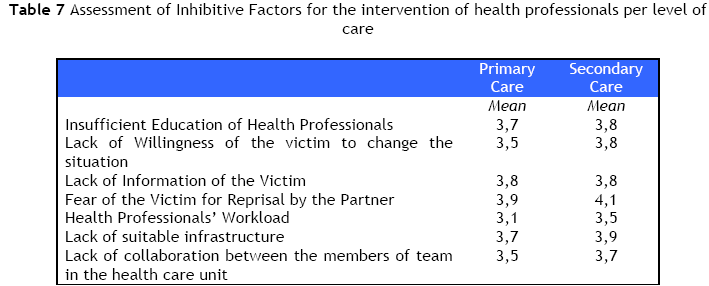

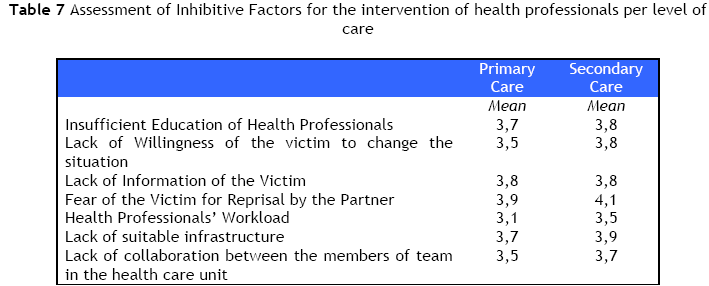

The next questions were related to the perception of health professionals with regard to the actions they may take within the boundaries of their role. In the question regarding the obstacles they face when dealing with victims of violence we could group the factors in two main categories: those related to the health professional or the health care setting and those related to the victim or her environment. As far as the first category is concerned, there was consensus from both health professionals in primary and in secondary care that the main obstacle is the lack of education, while they consider the workload to be of little importance. Finally, they also deemed the lack of infrastructure and the lack of collaboration between the different members of work teams as the most important factors in that respect. Regarding the factors which are related to the victim and its environment, both health professionals in primary and in secondary care regarded the fear of the victim for reprisal as the most important inhibitive factor. They also ranked highly the lack of willingness on the part of the victim to change the situation, as well as her lack of information or education

From the above it becomes clear that as far as inhibitive factors from the side of the health professional or his environment are concerned, the difference between health professionals in primary and secondary care is that the former found that their lack of education and lack of suitable resources were both ranked as first in importance, while their colleagues in secondary care ranked the lack of infrastructure as the most important obstacle. For the factors related to the victim and its environment, there was consensus that the most important obstacle is the fear of the victim for reprisal from the partner/ husband.

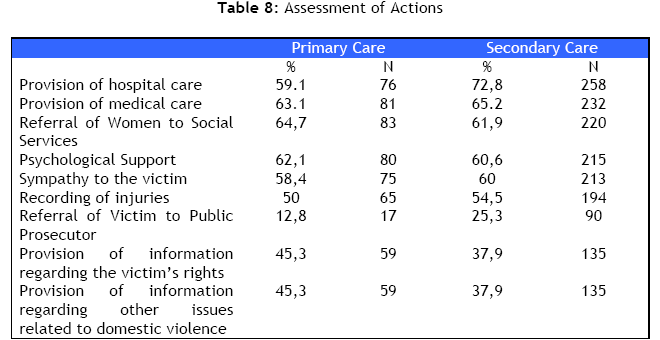

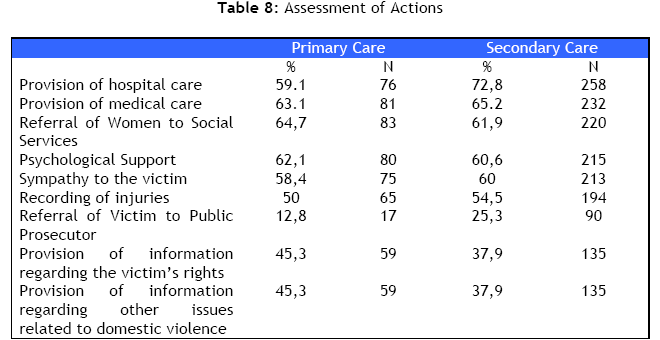

The last question aimed at the understanding of the attitudes of health professionals towards domestic violence and their perception of their role in dealing with this important public health issue. Health professionals in secondary care considered that the provision of hospital care would be their first priority (72,8%) while employees in primary care regarded the referral of the victim to the Social Services as their first priority (64,7%). Second in priority for health professionals in primary care and in secondary care was the provision of medical care to the victims. In the table below we can see the frequency with which health professionals rated the following items as high priority actions:

As it becomes clear from the table above, the referral of the victim to the authorities (by both professionals in primary and in secondary care) as well as the provision of information to the victim regarding its rights or other issues related to domestic violence (mainly by health professionals in secondary care) were deemed to be of low priority.

Discussion

From the data analysis it becomes clear that health professionals assess, based on their experience, that violence against women is a frequent phenomenon and has important consequences for the physical health of the victim. However, they find that the psychological impact to be larger and more important than the physical consequences for the victim. Furthermore, they detect the consequences it has for the victim’s family, a fact which is also proven in literature, where any form of violence in the family has been linked to important consequences for the psychological health of children, as well as for their socialisation [13,19]. More specifically, domestic violence has been positively linked to emotional behavioural and health problems [13] in children.

Health professionals were reluctant to associate domestic violence with negative effects in the social or professional life of the victim, as well as its importance for the physical well-being, whereas there are numerous relevant references in literature [2,19], as a battered woman may be physically or psychologically unable to be competent in the workplace, following an incident of violence in her home. Similarly, she may find that the emotional distress or the physical harm is preventing her from leading a normal social life.

Health professionals do not appear to be sensitized as far as the impact of domestic violence on the physical health of the victim is concerned, whereas this has been detected and emphasized in literature [4,5,8,20].. Health professionals mainly associate domestic violence with indications and symptoms such as injuries, hysteria and depression and less frequently so with spastic colitis and pelvic pain, although in literature there is ample proof of association of domestic violence with problems of the gastrointestinal system [4,21-23]. Furthermore, from the analysis of the answers given, it seems that health professionals in primary care are more sensitized than their colleagues in secondary care in the identification of such symptoms.

With regard to the training of health professionals, only a small number had participated in seminars or courses within or outside their formal education, The lack of education or training is regarded by health professionals as inhibitive to their effective dealing with victims of domestic violence within the boundaries of their professional role, thus expressing their need and desire for more and better training. Moreover, another important obstacle is the lack of suitable infrastructure in the health care system. They hold that the fear of the victim for reprisal from the partner is the largest obstacle from the side of the victim, although there are studies which prove that up to 80% of women welcome such screening [23]. Therefore, this fear of reprisal seems to be more of concern to health professionals than to women.

From the data analysis health professionals clearly express their need of and desire for better training as regards the treatment of victims of domestic violence. Another factor which is pivotal is the role of health professionals in the early detection of such cases as well as their part in referring victims to the appropriate authorities. Health professionals hold that the creation of suitable infrastructures may facilitate them in order to take suitable action. Although health professionals regard the fear of the victim for reprisals as the most important inhibitive factor, they also think that more and better information of the victims with regard to domestic violence in general and the rights of the victims more specifically would be useful and positively contribute to dealing with the issue.

In conclusion, the provision of education and information to medical and other staff both in primary and secondary health care as well as to possible or actual victims with regard to their rights and consequences to their health are deemed necessary. Finally, the development of suitable infrastructures in the health care system was judged by health professionals as critical towards the effective treatment of such cases by health care professionals both in primary and in secondary health care settings.

Conclusion

Our study has exhibited the willingness of health professionals to intervene and offer their professional services to abused women. Health professionals find the lack of infrastructure and the fear of the victim for reprisal by the aggressor as the key obstacles to their involvement. Health professionals associate domestic violence mainly with psychological risk and seem to underestimate the risk it poses for a woman’s general health despite the numerous such references in literature [4,5,8,20]. This, together with the fact that only a small fraction of them has ever participated in a seminar or had a course in their studies, clearly shows that health professionals could benefit from a specialised training and clear guidance on the management of cases of abused women. Moreover, the creation of suitable infrastructure could help to this end.

3644

References

- Kilpatrick D.G., (2004), What is Violence Against Women? Defining and Measuring the Problem, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19: 1209-1234

- Krug E.G., Dahlberg L.L., Mercy J.A., Zwi A.B., Lozano. R. (Eds), (2002), World Report on Violence and Health, World Health Organization

- World Health Organisation - WHO, (1997), Violence against Women, Health Consequences, WHO

- Perona M., Benasayag R., Perello S., Santos J., Zarate N., Zarate P., (2005), Prevalence of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Women Who Report Domestic Violence to the Police, Clinical Gastroenteroly and Hepatology, 3: 436-441

- Basile K.C., Arias H., Desai J., Thompson M.P., (2004), The Differential Association of Intimate Partner Physical, Sexual, Psychological, and Stalking Violence and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in a Nationally Representative Sample of Women, Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17: 413-421

- Greenfield L., Rand M., Craven D., (1998), Violence by Intimates: Analysis of Data on Crimes by Current or Former Spouses, Boyfriends and Girlfriends. Washington DC: US Department of Justice

- Lemon S.C., Verhoek – Oftendahl W., Donnelly E. F., (2002), Preventive healthcare use, smoking, and alcohol use among Rhode Island women experiencing intimate partner violence, Journal of Women’s Health and Gender-based Medicine, 11: 555-562

- Plichta S.B., (2004), Intimate Partner Violence and Physical Health Consequences, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19: 1296 – 1323

- Androulaki Z, Rovithis M, Tsirakos D, Mercouris A, Zidianakis Z, Kakavelakis K, et al. (2006), The phenomenon of women abuse, attitudes and perceptions of health professionals working in health care centers in the prefecture of Lasithi, Crete, Greece, 1st Panhellenic Congress for Health Scientists working with patients suffering from chronic diseases.

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, (2003), Costs of Intimate Partner Violence against Women in the United States, Atlanta GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Greek Center of Gender Equality Studies (KETHI), (2003), Intrafamilial Violence against Women: First Pan-Hellenic Research

- Thompson R.S., Rivara F.P., Thompson D.C., Barlow W.E., Sugg N. K., Maiuro R.D., (2000), Identification and Management of Domestic Violence, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 17: 5-9

- Ramsay J., Richardson J., Carter Y.H., Davidson L.L., Feder G., 2002, Should health professionals screen women for domestic violence? A systematic review, British Medical Journal, 325:314

- Butterworth P., (2004), Lone Mothers Experience of Physical and Sexual Violence: Association with Psychiatric Disorders, British Journal of Psychiatry, 184: 21-27

- Family Violence Prevention Fund, (2004), National Consensus Guidelines on Identifying and Responding to Domestic Violence Victimization in Health Care Settings, στο https://www.endabuse.org/programs/display.php3? DocID = 2006, (12-05-06)

- Davidson L., Grisso J., Garcia-Moreno C., Garcia J., King V., Marchant S., (2001), Training Programs for Healthcare Professionals in Domestic Violence, Journal of Women’s Health, Gender-Based Medicine, 10: 953-969

- Caralis P.V., Musialowksi R., (1997), Women’s Experiences with Domestic Violence and their Attitudes and Expectations Regarding Medical Care of Abuse Victims, Southern Medical Journal, 90: 1075-1080

- Hoff L.A., Rosenbaum L.A., (1994), Victimization Assessment Tool: Instrument Development and Clinical Implications, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 20: 634-637

- Stover Smith C., (2005), Domestic Violence Research: What have we learned and where do we go from here?, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20: 448-454

- Koloski N.A., Talley N.J., Boyce P.M., (2005), A History of Abuse Community Subjects with Irritable Bowel Symptom and Functional Dyspepsia: The Role of Other Psychosocial Variables, Digestion, 72: 86-96

- Corbally M.A., (2001), Factors Affecting Nurses’ Attitudes towards the Screening and Care of Battered Women in Dublin A&E Departments: A Literature Review, Accident and Emergency Nursing 2001, 9: 27-37

- Zachary M.J., Schechter C.B., Kaplan M.L., Mulvihill M.N., (2002), Provider Evaluation of a Multifaceted System of Care to Improve Recognition and Management of Pregnants, Women’s Health Issues, 12(1):5-15

- Loxton D., Schofield M., Hussain R., Mishra G., (2006), History of Domestic Violence and Physical Health in Midlife, Violence Against Women, 12: 715-731