Keywords

Quality improvement; Community mental health; Key working; Service user centeredness; Shared involvement

Introduction

Since the establishment of the Mental Health Commission (MHC), pursuant to Mental Health Act 2001, [1] there has been a discernible move towards family centred care in Irish mental health services. Family centred care was also the focus of the National Service User Executive (NSUE) directive to encourage collaborative work in the planning and delivery of services across the Republic of Ireland (ROI) [2]. The process requires equal opportunity for patients and families to be active participants on decision making bodies. NSUE established local consumer panels within each mental health service area in the ROI to move this forward [2].

The MHC identifies key working as a quality standard [3]. The south sector consumer panel suggested key working as a service improvement as no named healthcare provider was responsible for coordinating a service user’s care pathway from entry to exit of the service. This report describes the co-production design and testing of key working processes using the Model for Improvement in two mental health community centres in the south sector in the ROI.

Model for Improvement

The Model for Improvement, developed at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), embraces an iterative trial and learning approach [4] that is widely regarded as the basis for healthcare improvement across the United Kingdom, Europe and United States of America [5]. Improvement relies on small sequential cycles of learning, Plan Do Study Act (PDSA), which are driven by the three fundamental questions of the Model for Improvement [4]. Although the model has been criticised for its simplicity and suggested as only appropriate for small scale change [6], it is revered as an overarching framework and modern approach to system improvement [5]. Senior leadership endorsement, service user engagement, collaborative working, measurement for improvement, learning and development are central principles underpinning the success of this model in practice [6].

Background

The site

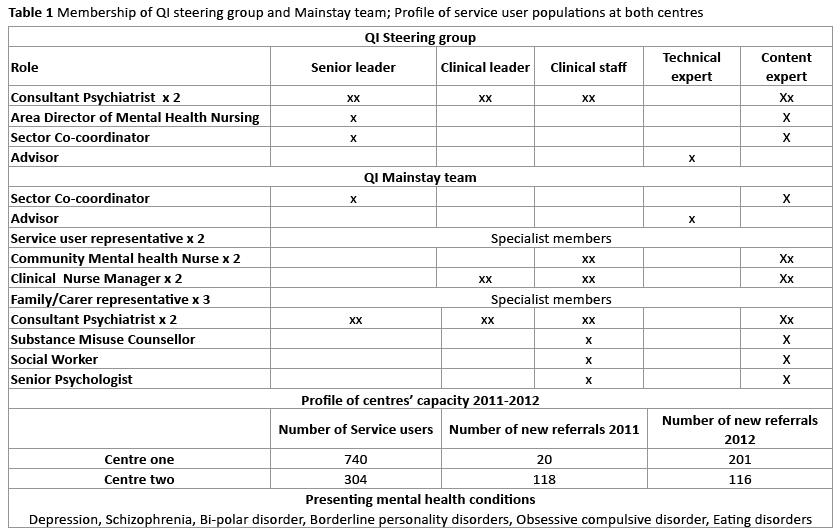

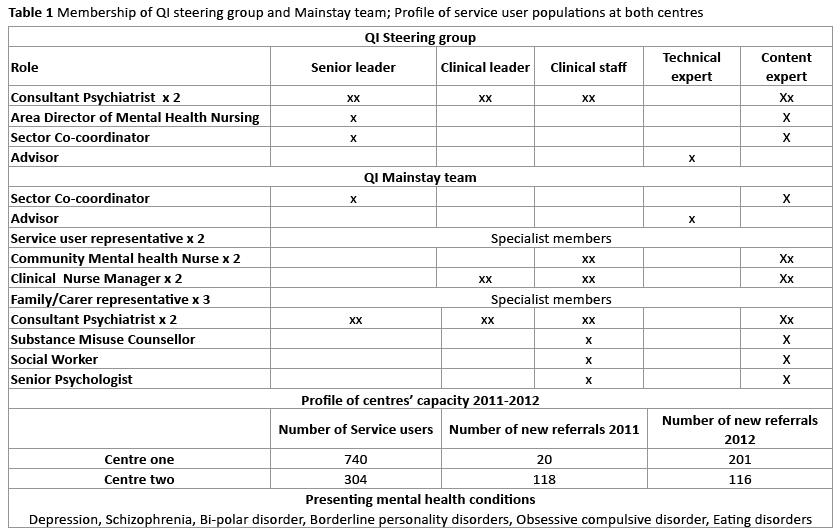

The community mental health centres’ multidisciplinary (MDT) teams provide service users with care and treatment to help them to manage their conditions in the community [7]. At the time of this QI initiative, the service user populations at both sites were similar with differences only in centre capacity (Table 1). Service users present to the centres with mental health conditions that include depression, schizophrenia, bi-polar disorder, borderline personality disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder, and eating disorders. Service users include people that have had one or more previous admission to the mental health services and first time users (new referrals) to the service. The service usercentred focus of this project applied to all persons presenting to the mental health service for the first time as a self or General Practitioner referral, or to persons that had not attended the mental health service for a period greater than one year.

Quality improvement teams

Involvement and support from the project sponsor, clinical and senior leaders, service users/family/carer representatives, and service users was critical to sustain collaborative engagement to achieve desired outcomes. A stakeholder analysis was used to identify and prioritise who and at what level people needed to be involved in the QI initiative [8]. This process determined the membership of a Steering group and Mainstay team.

The Steering group were responsible for resourcing the project. The principal functions of the Mainstay team were to develop and test change interventions, measure and analyse for improvement, ensure iterative communications with colleagues, and to report monthly to the Steering group. The Mainstay team met fortnightly at alternate centres. A buddy system operated to ensure constant MDT service user and family/carer representation at team meetings, and to share testing, measurement and analytic responsibilities. Table 1 also includes membership of the Steering group and Mainstay team.

Outline of problem

The south sector community mental health service implemented a purposefully designed Common Assessment Tool (CAT) that included an initial assessment in 2011 [7]. At that time the CAT project team envisaged a natural progression to key working. However service users continued to report inconsistency in the co-ordination and planning of care. They sought to develop a trusting professional relationship with a named healthcare professional that would be their principal point of contact in the service throughout their journeys to recovery.

New referral CATs were allocated at weekly MDT meetings to a healthcare provider based upon predicted requirements for professional interventions/ therapies. However referral details were often inadequate. This posed several challenges. A principal component of the CAT initial assessment was the co-creation of a care plan with a service user that included agreement of interventions/therapies. If established interventions/therapies were outside a healthcare professional’s expertise, the service user would have no further interactions with his/her first contact. In addition, some healthcare providers were allocated considerably more CATS than other colleagues based on anticipated service user need.

Typical shared involvement in QI at this service was through consultative processes and consumer panel communications. It was agreed at the inaugural Steering group meeting that a coproduction QI initiative could increase the likelihood of success in developing and implementing a fit for purpose sustainable change intervention, as co-production is based on the principle that those who are affected by a service are best positioned to help design it [9].

Aim of the project

The aim was to improve the experience for new referral service users seeking mental health services and for families/carers in the two community mental health centres. The primary outcomes were that 95% or more of new referral service users and 95% of family/carers would each rate positive statements regarding their experiences as 4 (agree) or 5 (Strongly agree) on Likert scales by July 2013.

The impact of desired outcomes was staged so that the likelihood of success could be assessed throughout the QI journey. An external Advisor supported the Mainstay team from May to December 2012. Measurement of incremental outcomes was necessary to indicate if extended advisory support would be required in the future. The staged goals were that 20% or more of new referral service users and family/carers would rate their experiences as 4 or 5 by December 2012 and 50% or more would rate their experiences as 4 or 5 by March 2013.

Method and Material

Measure for improvement

Robust accurate measurements of what was happening were fundamental to knowing if changes were producing improvement [10]. The Mainstay team and Advisor supported stakeholders in the development of health literate measurement tools. Mainstay service users and family/carer team members identified critical factors that could influence stakeholders’ experiences. Service users identified, welcome, listening, information exchanged in an understandable way, and trust as the main factors that impacted on their experiences. Family/carers also identified these, but in addition included provision of comfort and information of further support resources. Statements focusing on these factors were fashioned using the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) model [11], and then tested for health literacy before further testing with service users and family/carers. This development of outcome measurement tools, while effective, was time consuming. To accelerate the process, a facilitated on-site focus group with 12 service user participants, guided by an experience based design (EBD) approach [12], used PDSA test cycles to develop a fit for purpose questionnaire to measure meaningful experiences [13]. This process ensured data quality, validity and reliability of assessment instruments. Small random monthly samples generated just enough data, n=60 service users for a return of 40.

Attempts to organise a family/carer focus group was not possible due to stakeholder time and travel constraints. In this regard valuable lessons were learned in terms of the importance of early engagement with stakeholders using EBD and rapid PDSA test cycles to develop measurement tools.

A multi-method approach measured primary outcomes. Likert scales corresponded with word scales and were converted to attribute data to facilitate graphical illustration of outcomes in statistical process control charts (SPC). SPC was used to describe and quantify variation, and to assess the impact of changes. However the small data sets for some measurements potentially limited its application. Nonetheless, rich excerpts from interviews with key stakeholders supported understanding of the emic experience in a real world context, supported assessment of the impact of improvements, and helped to predict future trends. A family of outcome, process, and balancing measures ensured the successful generation of vital few measures only.

Ethics

Senior leadership deemed this work exempt from ethics review as it was not intended for research purposes. Nevertheless all respondents to surveys and interviews were informed of the right not to participate, to withdraw participation at any point, and to refuse to answer any question. Surveys were completed anonymously to ensure blinding. The Advisor maintained overall responsibility for collection, analysis, reporting and security of data and findings. The Advisor was mentored by an external improvement expert and healthcare improvement institute throughout the QI initiative, and was accountable for best practice to a professional regulator.

The steering group approached local consumer panels established by the MHC to recruit service user and family/carer Mainstay team members. Participation was voluntary, however membership of the consumer panels provided a safe external forum for service users and family/carers to share their experiences of the QI initiative and any concerns that they may have had. It also provided a further external QI monitoring mechanism.

Process of gathering information: methods used to assess problems

Baseline measures were not available as the infrastructure did not support easy access to records, and discharged service users’ notes were secured at another location. Exploratory approaches were used to understand the problem and to support generation of change ideas. In 2011 the service developed a broad process map that outlined new referral service users’ journeys from entry to exit of the service [7]. The process map identified principal processes requiring change to improve experiences through key working.

A purposefully designed data collection tool “What is key working” generated a baseline understanding of what was understood and expected of key working in community mental health settings by stakeholders. All healthcare providers, service users and family/carers present in each centre on a random morning were sampled, n=46 (Response rate=67%). The principal understanding of key working that emerged was that a named healthcare provider as a key worker would collaborate with the service user to develop, co-ordinate and implement a care and recovery plan from point of entry to exit of the service. The key worker would also, with service user consent, be available to talk and liaise with family/carers.

Analysis and interpretation

The main roles and responsibilities extracted from the “What is key working “questionnaire set the context and background to develop new ideas through creative thinking snorkelling sessions with all healthcare providers and Mainstay team members. The sessions generated in excess of 400 change ideas and 90 themes. Analysis of themes, together with understanding the service user journey process map and discussion at mainstay team meetings, identified three critical key working processes that required design or redesign:

• Entry/assessment

• Shared Care/decision making

• Standardising the coordination of care

A change package, with multiple change interventions, was then developed for each process. Change packages were organic and often unplanned interventions developed as a consequence of change processes, such as the standardisation of appointment processes.

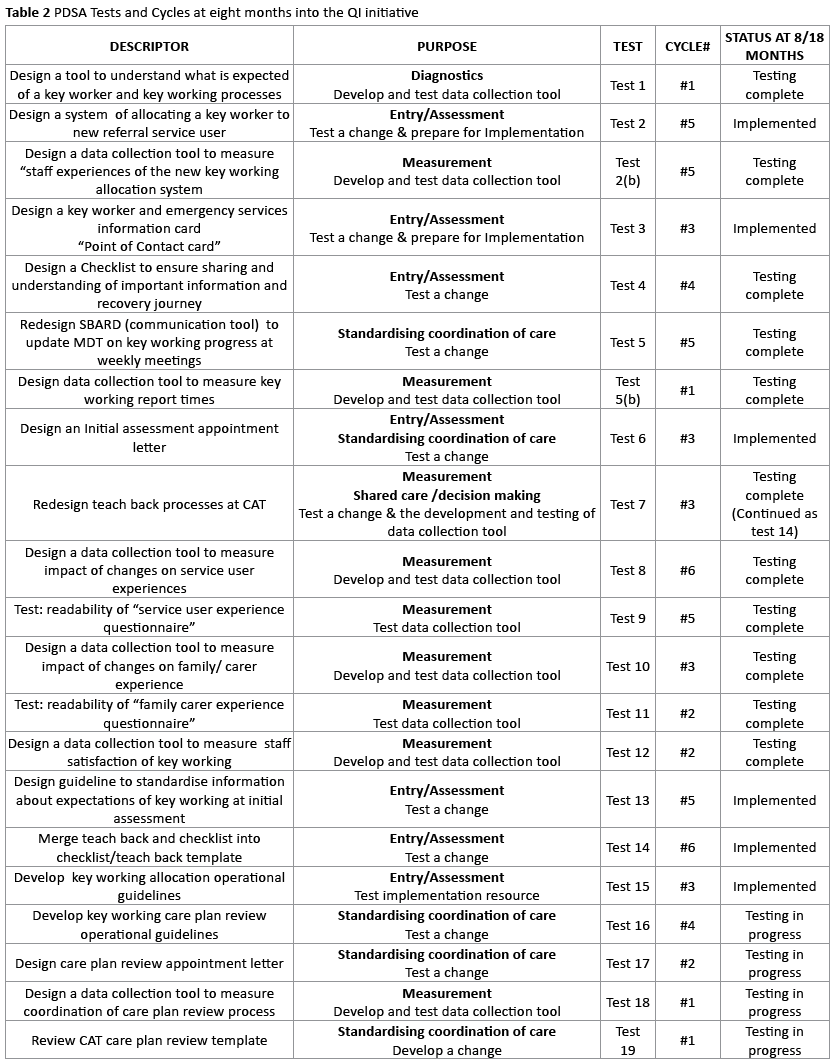

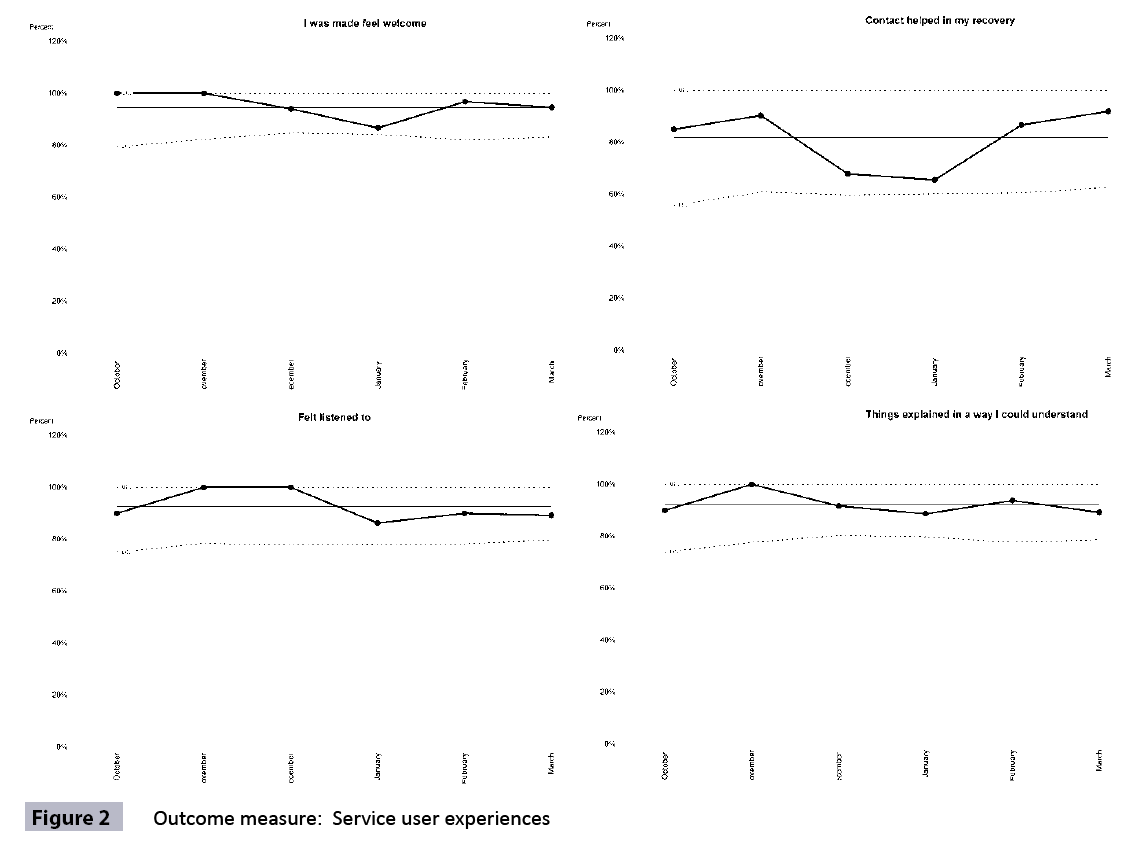

Verbal modified Failure Mode and Effect Analysis were conducted for each change intervention prior to testing. Iterative PDSA cycles that promoted a trial and error learning approach to change, [5] were used to test changes, to develop measurement tools, and to implement changes. Several PDSA tests had multiple cycles. Table 2 lists PDSA tests that were either completed or still in progress at the time of reporting and outlines the purpose and descriptor of each test.

Strategy for change

Planning, coordination, and effective communication strategies ensured that stakeholders were prepared for implementation. There are three main methods to implement a change: parallel, sequential and just do it [4]. Foremost principles determining the appropriateness of an approach include the complexity of the change, if phased implementation is necessary, and the number of components within the change [4]. Changes determined implementation approaches. PDSA cycles and checklists guided implementation processes. Measurement for improvement continued throughout implementation. All documentation and measurements for improvement are secured at one centre to facilitate a decision trail.

Results and Discussion

Effects of change

Change leads, supported by the Advisor, were responsible for sampling, generating and analysing a total of nine measures. SPC charts, run charts and qualitative data illustrated the impact of changes and variation in processes. Sampling methods differentiated stakeholder groups and centres, however stratification was not used. Identifying variation between subgroups and centres could have initiated a competitive process. Charts were annotated with interventions as tested.

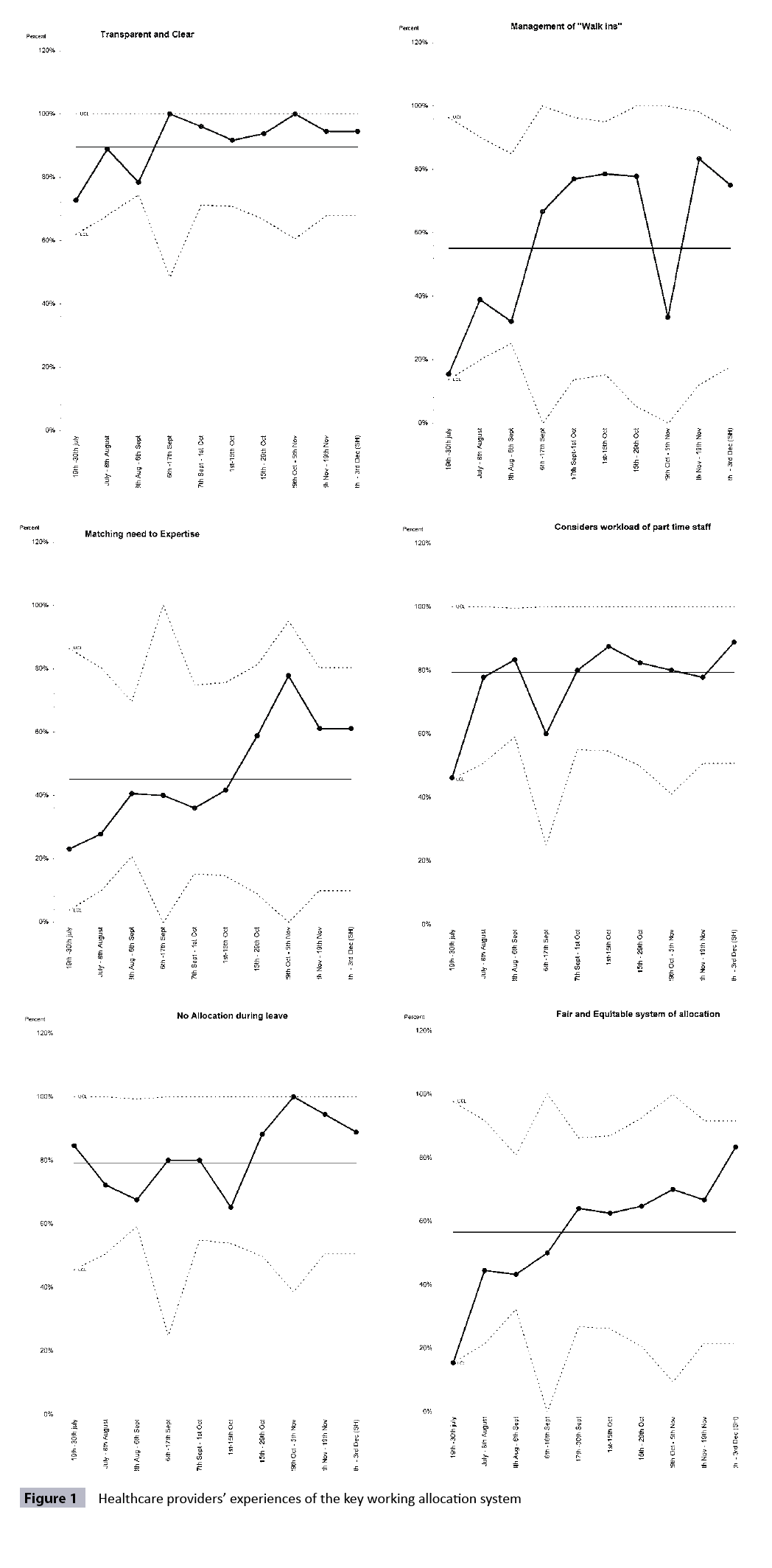

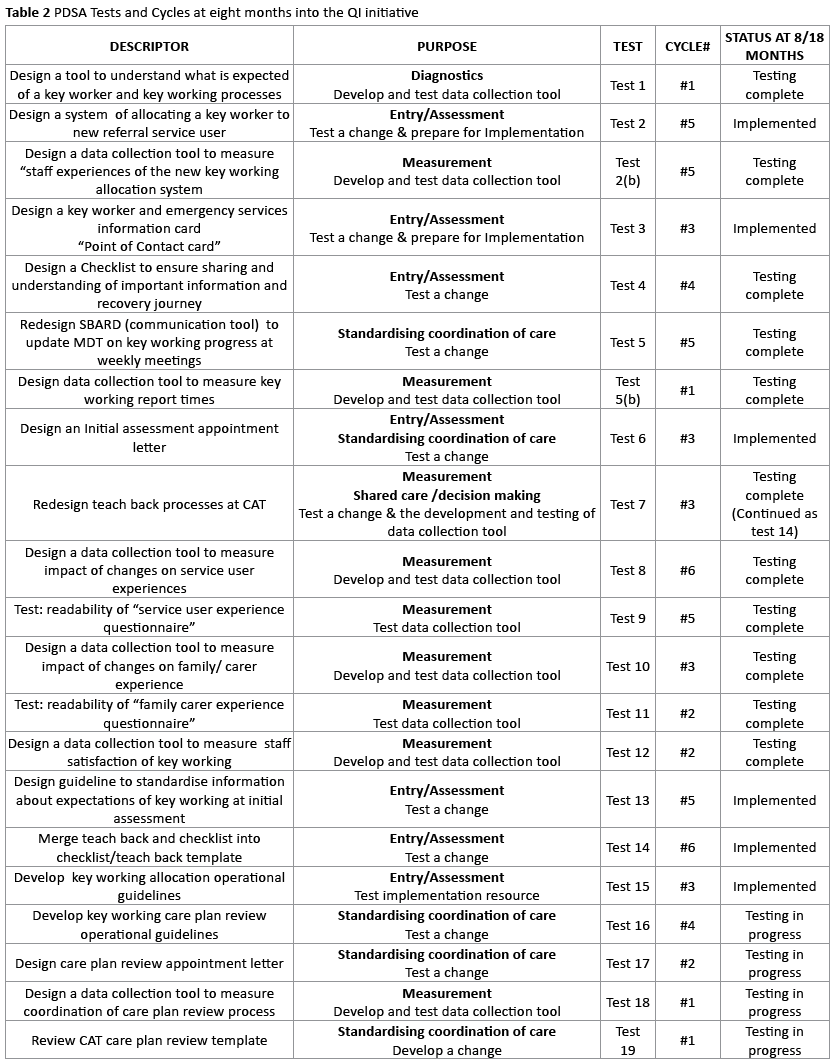

The welcome and introduction process required multiple change interventions. Service users wanted to develop a trusting relationship with the healthcare provider (key worker) that they met on first entering the service. Self-referral service users were colloquially termed “walk-ins”. It was therefore imperative that the development of a fair and equitable allocation system considered expertise and caseload, and facilitated allocation of a key worker to “walk-ins”. Throughout PDSA key working allocation system test cycles, all new referrals were allocated a key worker. This change intervention was the most significant transition to new beginnings [14] for healthcare providers and demanded careful attention to human factors. Using the PDSA approach healthcare providers developed a tool to measure their experiences of the key working allocation system. As small samples can generate just enough data in measurement for improvement [15], random samples of n=20 were sampled fortnightly for a return of 10. Figure 1 depicts the process measurements of healthcare provider’s experiences throughout testing and implementation of a new key working allocation system.

Figure 1: Healthcare providers’ experiences of Figure 1 the key working allocation system

At eight months into the QI initiative PDSA test and implementation cycles were still underway for some shared care/decision making and standardising/co-ordination change interventions. There were insufficient data points for some measures to predict future patterns or draw conclusions.

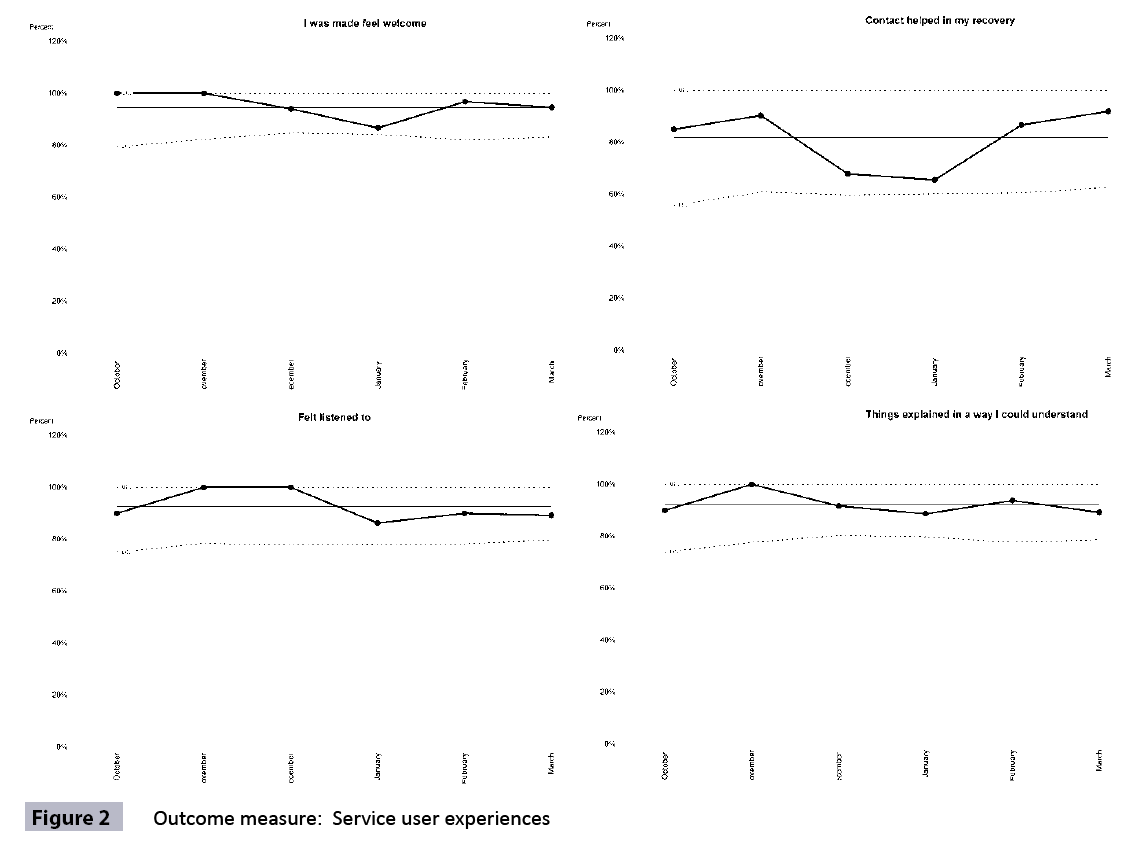

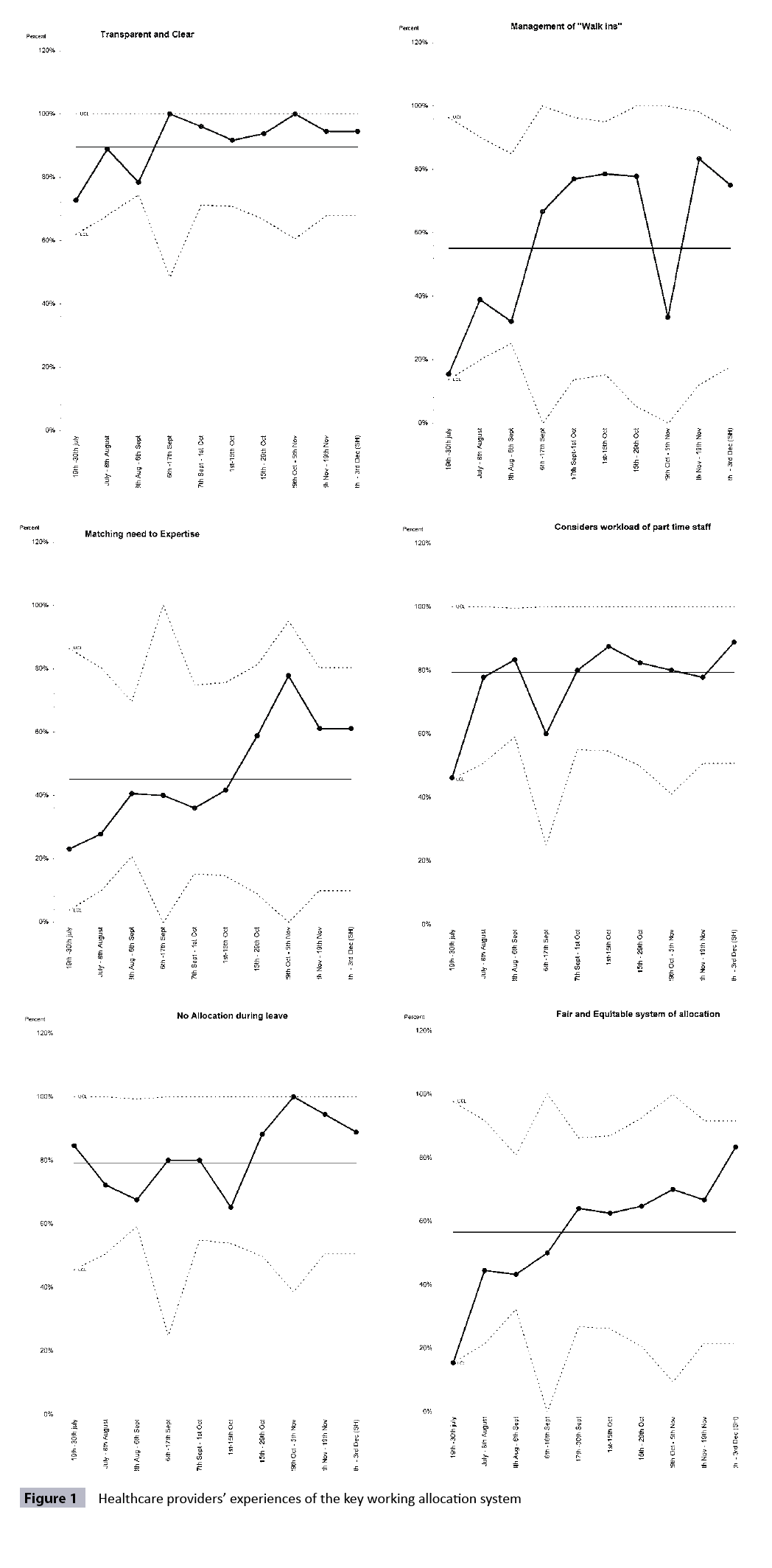

Figure 2 illustrates how change interventions impacted on service user experiences since measurement commenced in October 2012. The monthly response rate was ≥ 75% and measures suggested that the July 2013 goal, 95% or more service users rate a 4 or 5, would be met earlier than predicted. However the true impact is evidenced through experiences shared by service users in returned surveys:

Figure 2: Outcome measure: Service user experiences

“If I didn’t have them, I wouldn’t be where I am today”

“My voice was heard”

“Would be lost without them”

“Could not have coped without them”

“I am so grateful for everything thank God you are here”

“In my recovery the people I worked with never gave up hope for me and were very friendly and thoughtful”

(Service Users, 2012)

Family/carer mainstay team members in collaboration with other family/carers developed a survey to measure their experiences of the service as a primary outcome. Measurement commenced at both sites in November 2012. PDSA cycles tested several sampling strategies to engage family/carers at the micro level. However the response rate was insufficient to draw conclusions.

Process measurements of family/carer attendance at initial assessments suggested a stable process, but no improvement since commencing the QI initiative. Feedback from healthcare providers, reported an increase in family/carer attendance at therapy/intervention sessions. Perhaps this was a consequence of implementing intended and unplanned change interventions. One unplanned change had multiple benefits, reducing variation in scheduling processes and encouraging family carer involvement through a pre-assessment phone call and standard appointment letter encouraging family/carer involvement. Intended changes included explanation of the potential role of family/carers throughout recovery in a purposefully developed “guide to key working,” and at initial assessment when service users were asked to consent to family/carer involvement.

Mainstay family/carer and service user members were not surprised with the family/carer measurements, as their typical experience of family/carer involvement in care processes was complex and gradual. To inform future QI activity, a baseline of family/carer involvement as experienced by the service user was to be measured through an additional binary question in the service user experience questionnaire from December 2012.

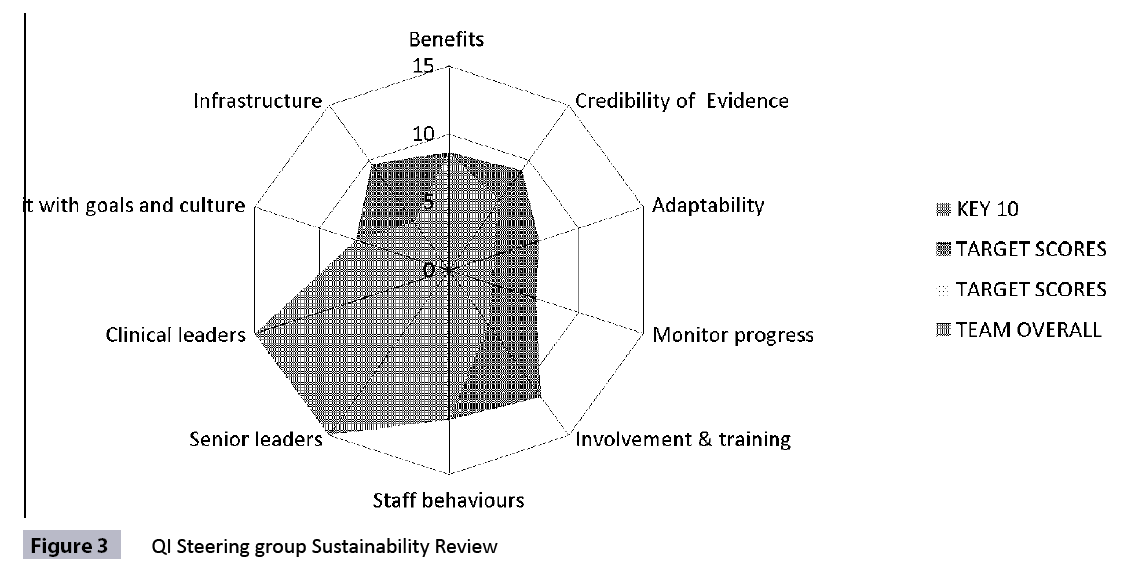

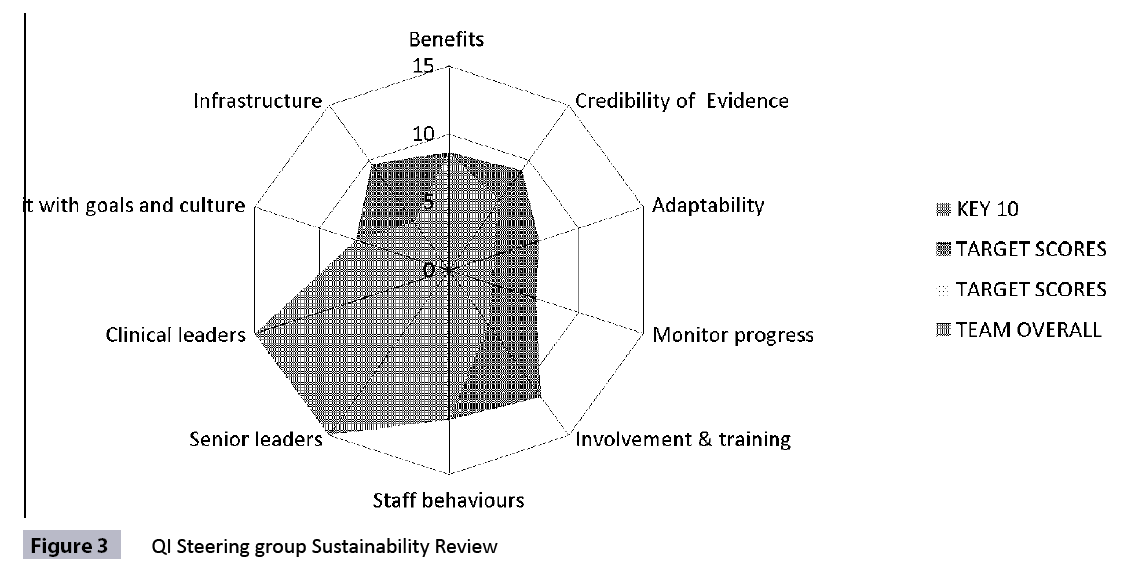

Sustainability

A fundamental objective of QI activity is sustainability [16,17]. In early October 2012, the steering group conducted a mid-project sustainability review [18]. The score, 79.2, provided good reason for optimism, as the sustainability guide suggests scores lower than 55 require action to increase the likelihood of sustainable initiatives [16]. Figure 3 illustrates mid project sustainability measurements. The mainstay team expected implementation of all change interventions by May 31st 2013. The intent of the steering group was that this model of key working could be spread to and adopted by other mental health services within the south sector to improve service user experiences once there was evidence of sustainable impact on the service user primary outcome. A final sustainability review was to be conducted in July 2013.

Figure 3: QI Steering group Sustainability Review

Learning and next steps

This QI initiative demonstrated some of the complexities in achieving meaningful family/carer involvement in mental health services. However it has provided the impetus and opportunity for a family/carer centred QI initiative in community mental health to increase active involvement in recovery.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are feasible for providing evidence of the impact of consumer involvement in healthcare decisions at the population level, but there is little evidence of this practice [19]. This QI initiative was not a RCT. However, an unintended outcome of this work was demonstrating the degree to which a co-production with service users and family/carers using an improvement methodology could realise successful outcomes through shared involvement. The Advisor interviewed and videotaped one mainstay service user member in late November 2012 to learn about his experience of the improvement journey. The service user shared that this QI initiative and coproduction was:

“…fundamentally… most important project in terms of real involvement, real partnership and real recovery… this is where it happens…open and welcoming, the improvement team bring a value base into a system that is so wrapped up in paper work… team members giving that bit extra in times when things are just being taken…there was no bouncer on the door we all can express our opinions, we have over time met understood and created better outcomes” (Mainstay service user member, 2012)

Service regulators reported that the south sector community mental health centres demonstrated efforts to promote active participatory engagement with service users and family/carers to provide a quality client centred service [20].

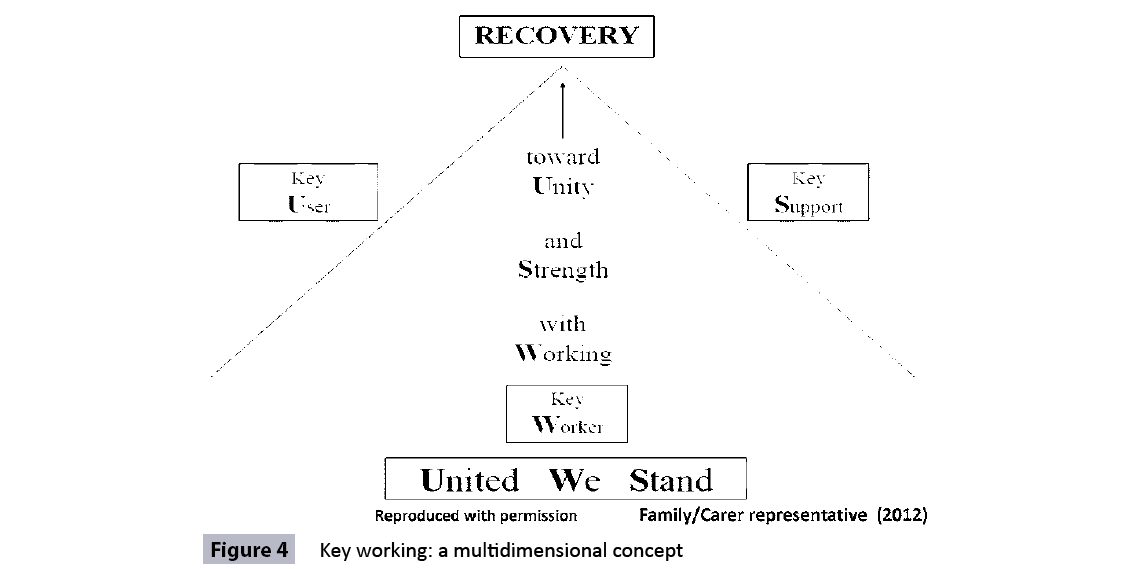

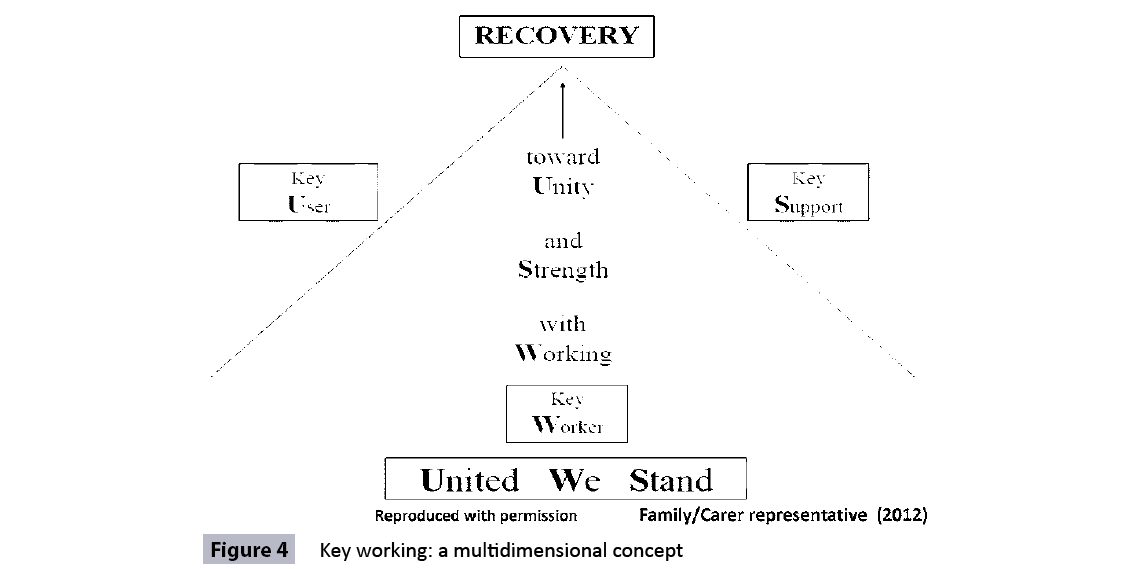

A family/carer representative voluntarily developed a poster, depicted in Figure 4, during the course of the QI initiative. This poster illustrated a principal stakeholder perception of key working as a multidimensional concept that extended beyond the sole responsibility of the healthcare provider.

Figure 4: Key working: a multidimensional concept

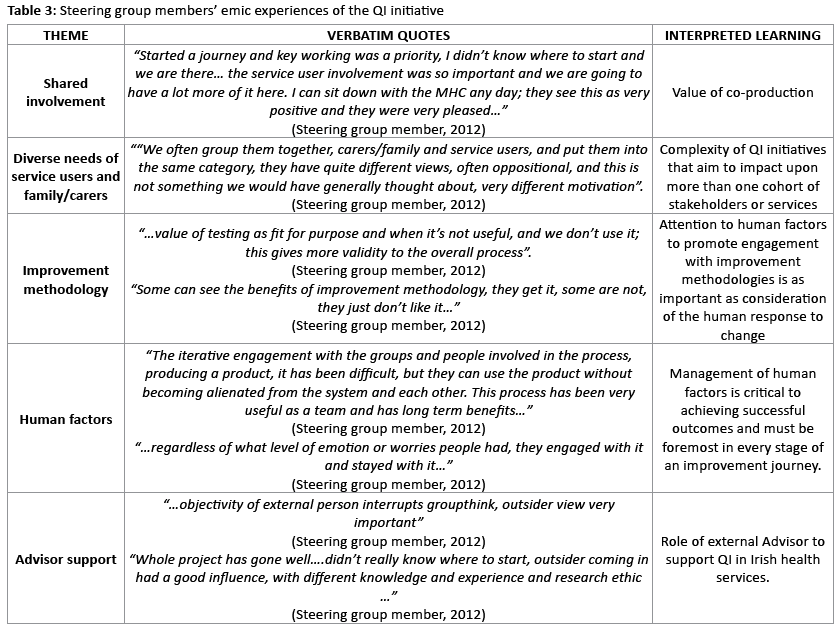

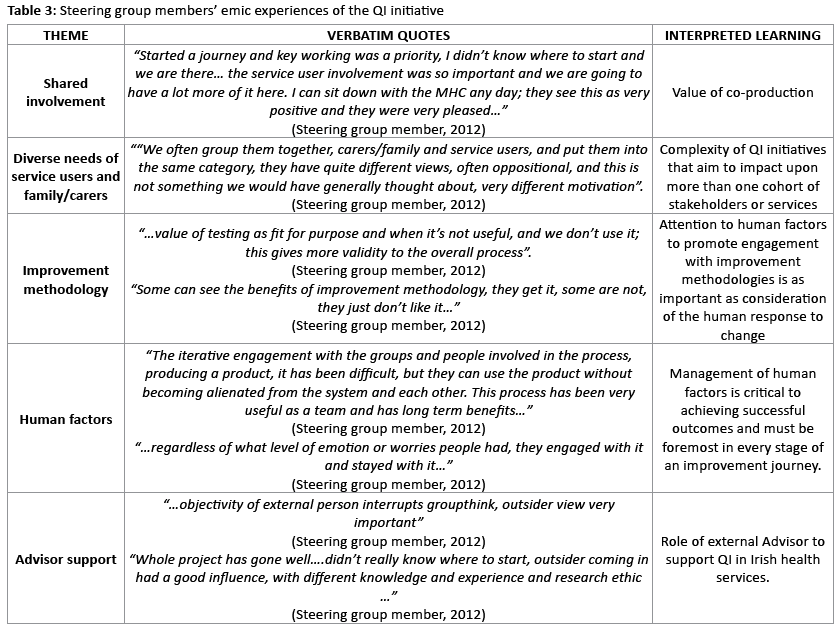

In November 2012, Steering group members shared their emic experiences of the QI initiative with the Advisor in one-to-one audio-taped interviews. The purpose of these interviews was to highlight issues that could impact upon sustainability, to inform future QI work in the service, and to evaluate the Advisor’s level of success in supporting the QI. Consent to participate was recorded and member checking used to validate interviews. Semi-structured topic guides directed the interview processes.

Thematic analysis was used to interpret phenomena of interest. Table 3 synopsises the main themes with supporting verbatim quotes, and interpreted learning.

Conclusion

The purpose of this service user-centred QI initiative was to improve the service user and family/carer experience in the south sector community mental health centres in the ROI. Early measures of improving the service user experience surpassed incremental targets and provided reason for optimism. The complexity of improving experiences for multiple cohorts with diverse needs was discovered throughout the course of this work. Measures for improving family/carer experiences were inconclusive and required further QI activity.

The QI journey yielded important learning for this service and potentially for the improvement community that includes, engendering and maintaining high level engagement of all stakeholders throughout the life of QI projects, the complexity of QI initiatives that aim to impact upon more than one cohort of stakeholders or services, and the effectiveness of using a blend of qualitative and quantitative approaches to measure for improvement. However the most significant learning was that service user/family centeredness extends beyond involvement in the design, testing and implementing fit for purpose processes to co-productions that are valued as important and experienced as meaningful by all stakeholders.

Acknowledgements

Senior management team and project sponsor; Kevin Plunkett, Kay Cullen, healthcare providers, service users and families and carers in the south sector community mental health centres. Wave 23 IHI Improvement advisors and IHI Faculty members; Ron Moen and Jane Taylor.

3796

References

- Government of Ireland (2001) Mental Health Act Ireland. Irish Statute Book

- National Service User Executive (2009) The Strategic Plan of the Interim National Service Users Executive 2007-2009

- Mental Health Commission (2012) The Quality Framework for Mental Health Services in Ireland

- Langley GL, Moen, RD, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, et al.(2009) The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to EnhancingOrganizational Performance. (2nd edn), Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco

- Boaden R, Harvey G, Moxham C, Proudlove N (2008) QualityImprovement. Theory and Practice in Healthcare. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, Coventry, United Kingdom

- Berwick DM (1996) A primer on leading the improvement of systems. BMJ 312: 619-622

- NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (2010) The Handbookof Quality and Service Improvement Tools. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, Coventry, UK

- NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (2006) Patient Experience Network. NHS Institute for Innovation and ImprovementCoventry, UK

- Batalden PB, Davidoff F (2007) What is "quality improvement" and how can it transform healthcare? Qual Saf Health Care 16: 2-3.

- Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (2012) HCAHPS Fact sheet USA: (CAHPS® Hospital Survey) May 2012

- Baxter H, Mugglestone M, Maher L (2010) The ebd approach –Guide and Tools Experience Based Design: Using patient and staffexperience to design better healthcare services. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, Coventry, UK

- Bate P, Robert G (2006) Experience-based design: from redesigning the system around the patient to co-designing services with the patient. Qual Saf Health Care 15: 307-310.

- Bridges W, Mitchell S (2013) Leading Transition: A new model for change. Eaton & Associates Ltd, Berlin

- Clarke J, Davidge M, James L (2009) The How-to Guide for Measurement for Improvement. Patient Safety First, UK

- NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (2011) Sustainability Guide. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, Coventry, UK

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement (2008) Protecting 5 MillionLives Campaign. Getting Started Kit: Rapid Response Teams. Cambridge, MA

- NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (2011) Sustainability Model. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, Coventry, UK

- Mental Health Commission (2013) Mental Health Services: South Wexford Community. Mental Health Commission, Dublin.