Keywords

stress, job satisfaction, mental health nurses, psychiatric nurses, doctor-nurse collaboration, assistant nurses, nursing leadership.

Introduction

There is considerable research on work satisfaction and stress in general nursing, however, compared to other clinical specialties, relatively little attention has been paid to mental health nurses [1,2,3]. A previous research review of factors influencing stress and job satisfaction of nurses working in psychiatric units, carried out by the authors, revealed that poor professional relationships have been identified as a frequent stressor for mental health nurses working in hospitals.1 Problems in professional relationships are manifest in the lack of collaboration between doctors and mental health nurses, conflicts between nurses, and lack of doctors’ respect for nurses’ opinions and their participation in decision making about patients’ care [3,4,5,6,7,8].

Mental health nurses are also stressed by difficulties in relationships and conflicts with other staff nurses they work with. From the studies discussed in a previous research review [1], the authors concluded that there is a negative relationship between stress and good professional relationships between nurses and doctors, and also amongst mental health nurses. Thus, nurses who have low levels of stress will have collaborative relationships with doctors and other nurses, and those with high stress will have poor relationships with colleagues.

Stress and clinical leadership of ward line managers (head nurses) have not been examined specifically in relation to each other in previous studies, but clinical leadership has been found to be a major influence on the stress of mental health nurses [6,7,8,9,10]. The role of the head nurse has emerged from previous studies as of paramount importance in establishing a cooperative working environment, which fosters low stress and high job satisfaction for the staff. In addition, the literature stresses that lack of a skilled head nurse to resolve conflicts amongst nurses and to be supportive is an influential factor that increases mental health level of stress [1]. Lack of these skills has a negative relationship with mental health nurses’ occupational stress [1]. Moreover, it seems from the literature that the team building skills of the head nurse is positively associated with the quality of professional relationship amongst nurses [1].

Although few studies have been conducted, it seems that there is a consensus in the literature with respect to the strong negative association between stress and job satisfaction in mental health nurses[1]. Studies report that different sources of stress are perceived by nurses in the work environment and that stress decreases nurses’ job satisfaction [1].

The factors influencing job satisfaction in registered mental health and assistant nurses are uncertain because of the limited empirical investigation in this field [1]. In addition, it seems that nurses’ level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction varies according to the type of unit they work in [11]. In one study, psychiatric nurses were satisfied working in an acute care psychiatric unit [11] and in another study they were dissatisfied [12]. The findings of the studies examining job satisfaction in psychiatric assistants are more congruent with the predictors of job satisfaction reported by general nurses [13]. For example, factors relating to the quality of professional relationships between nurses and doctors and amongst nurses’ co-workers and supervisors, appear to contribute to nurses’ job satisfaction [14,15]. Furthermore, the leadership ability of the head nurse and his/her relationships with the nursing team emerge as an important factor in predicting job satisfaction of mental health nurses working in acute care settings; these studies show a strong positive association between a supportive line nurse manager and nurses’ job satisfaction [1]. Thus, the literature shows a positive relationship between inter-professional working, clinical leadership and job satisfaction. However, with the exception of the clinical leadership, which seems to have a strong association with job satisfaction, other variables do not have straightforward associations. Overall, we have only limited knowledge about the factors that contribute to mental health nurses’ job satisfaction.

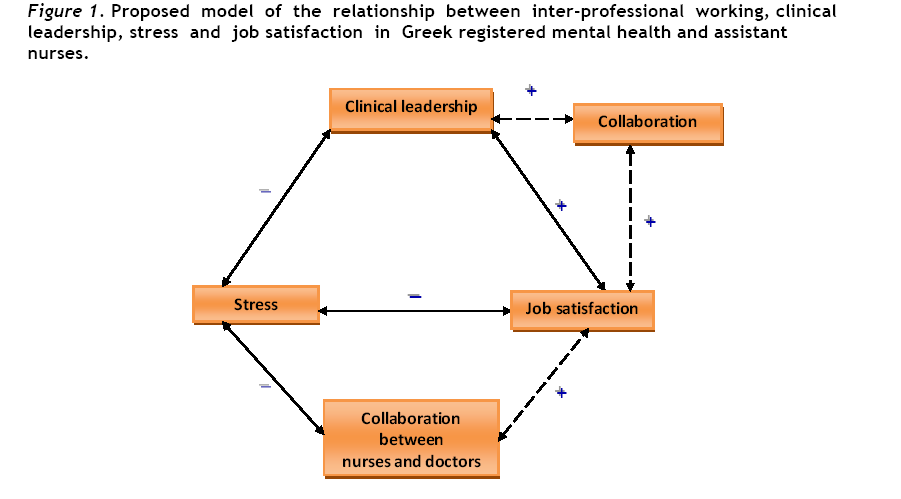

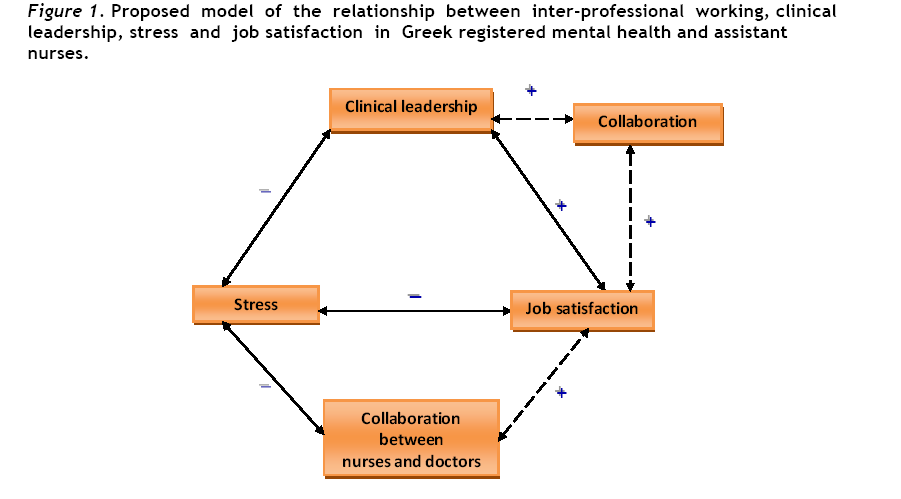

The findings of a previous research review [1] suggested a possible model for stress and job satisfaction in psychiatric nursing part of it tested in the present study (fig. 1). In particular, the model shows occupational stress to be negatively related to mental health nurses’ job satisfaction, the clinical leadership of the head nurse, the quality of professional relationships amongst nurses and between nurses and doctors. In addition, Job satisfaction is positively related to the quality of professional relationships amongst nurses, and between nurses and doctors as well as the clinical leadership (the team building skills) of the head nurse. Furthermore, the clinical leadership of the head nurse is related positively to professional relationships amongst nurses working in a psychiatric speciality.

Figure 1: Proposed model of the relationship between inter-professional working, clinical leadership, stress and job satisfaction in Greek registered mental health and assistant nurses.

This model shown in Fig. 1 depicts the expected relationships between the variables that influence stress and job satisfaction in nurses working in psychiatric units. Therefore, the expected directions between the variables are described either with the solid arrows which represent strong relationships between them as supported by the literature, or with the dotted arrows indicating possible associations less obvious in previous research review [1]. The plus sign indicates that the variables are expected to be positively related and the minus sign indicates that an inverse association is expected.

Understanding the relationships between these variables, which have not been studied previously, is important because such knowledge can guide possible changes, within working environment and identify area for future research.

METHODOLOGY

Aims, objectives and hypotheses

The aim of the study was to test the hypothetical model of the relationships between inter-professional working (professional relationships amongst nurses and between nurses and doctors), clinical leadership (the team building skills of the head nurse), stress and job satisfaction in mental health registered and assistant nurses (Fig. 1).

The objectives of this study were to

1. Identify major stressors perceived by Greek registered mental health and assistant nurses.

2. Measure the level of occupational stress and job satisfaction of Greek registered mental health and assistant nurses.

3. Test aspects of the model emerged from a previous research review [1]. This involved testing the following hypotheses:

a) There is a negative relationship between occupational stress and perceived job satisfaction, clinical leadership (team building skills of the head nurse), and quality of professional relationships amongst nurses and between nurses and doctors.

b) There is a positive relationship between job satisfaction and clinical leadership, as well as quality of professional relationships amongst nurses and between nurses and doctors.

c) There is a positive relationship between clinical leadership and professional relationships amongst nurses.

Research design

This research study adopted a cross-sectional correlational design. The correlational design facilitates identification of the inter-relationships between the variables studied bringing to light more information on the overall picture of a situation being explored [16,17].

Sample and research site

The study was conducted in six public Greek hospitals to which acute psychiatric care units were attached. Subjects of this study were all the registered mental health and assistant nurses who worked in the units where this research was conducted. From the study excluded the head nurses of each unit because factors related to their leadership position and their role were measured. Respondents directly involved in delivery of nursing care to patients in acute psychiatric wards, and working full time on a shift basis.

The research instrument

Data were collected using a questionnaire comprising six instruments:

The Mental Health Occupational Stress Scale (MHPSS) [18]. It comprises 42 items which describe situations that have been identified as causing stress for mental health professionals and it is divided in seven subscales. These are workload, client-related difficulties, organizational structure and processes, relation and conflicts with other professionals, lack of resources and home-work conflict. Each item is answered on a 4-point response scale scored from 0 (does not apply to me) to 3 (does apply to me). It has been shown to have very good internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha 0.94.18

Professional working relationships [19] (21 items) designed to measure the quality of relationships between nurses and doctors.

Professional working relationships [19] (19 items) measures the professional relationships amongst nurses [19].

Ward Leadership Scale [19] (9 items) which addresses the team building skills of the head nurse as perceived by nursing staff.

Job Satisfaction Scale developed by Adams and Bond [19] (13 items) refer to the reward of the job. All the above scales developed by Adams and Bond [19] answered on a four-point Likert-type response from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) providing a total score. In addition, the aforementioned scales have shown reliability with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.77 to 0.92 and in test-retest Pearson correlation coefficient from 0.77 to 0.90.

All the scales used in the present study translated from English to Greek and then from Greek to English (back translation).

Demographic questionnaire which included professional characteristics namely, level of nursing education, specialization in mental health nursing, years of experience in the psychiatric unit, the total years of experience as nurse. In addition, single item asked respondents to rate the extent they felt stressed on a 7-point scale from 1 (not stressed) to 7 (very stressed).

Data collection procedures and ethical issues

Each subject who invited to participate information was given as required, and was guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality of the information collected. Participants were not asked for their names on the questionnaire. Consent to participate was assumed to have been given by those who completed and return the questionnaire.

Pilot study

The feasibility and acceptability of the questionnaire was tested in a pilot study in a psychiatric ward not involved in the main survey. Overall the pilot study showed that no major changes in structure or content of the questionnaire were needed. Two items in the MHPSS18 were modified to increase clarity for the Greek respondents. These were “terminating with client/patients which changed to “terminating the relationship with a client/patient who is going to be discharged”. In addition, in the same scale the item “Dealing with death and suffering” changed to “the contact in my working environment with patients either who are terminally ill or they are suffering”. One item in Job satisfaction scale [19] was modified to apply in the Greek nurses employees. This was “I am satisfied with my clinical grade” changed to “I am satisfied with the assessment of my qualifications by the hospital I work”. From the pilot study the questionnaire appeared to have face validity as the questions were considered to be relevant to the aim of the study.

Data analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistics were employed in analyzing the data. To establish validity the MHPSS overall score was concurrently tested with the self-report scale, using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient r (two-tailed test). Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (one tailed test) was used to assess the relationship between the scores obtained on collaboration between nurses and doctors and amongst nurses, ward clinical leadership and the total score obtained on stress and job satisfaction respectively. As the data were not normally distributed, again it was appropriate to use Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

The sample size for this study (n=85), achieved a power of 80%, at 5% level of significance, which was sufficient to identify a medium size effect. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 15). With respect to model after testing only the significant associations that supported the hypotheses of this study have accepted.

RESULTS

Demographic data

A sample size of 85 nurses (n=85) was obtained from a target of 120 registered mental health and assistant nurses, giving a response rate of 70.8 %. The respondents mean age was 36 years (SD=7.3). From the sample 53 (n=53) were registered nurses (21 male and 32 female) and 32 (n=32) were assistant nurses (19 female and 13 male). The proportion of the respondents who were married was 63% (n=55), 40% had no children (n=34). Most of the registered nurses (n=39;60%) had been specialized in mental health nursing and many of the registered mental health and assistant nurses had worked on their ward between 6-10 years with total working experience in a hospital between 4-25 years respectively. The majority of the registered and assistant nurses had only worked in their current psychiatric ward.

Mental Health Professional Stress Scale (MHPSS)18

Scores on the Mental Health Professional Stress Scale [18] showed that registered mental health and assistant nurses experienced moderate levels of stress (mean 69.30; SD=19.28). Of the seven subscales lack of resources was the most highly rated source of stress (mean:11.65;SD=4.01). The three most frequent stressors from this subscale were ‘lack of adequate staffing’, ‘lack of adequate cover in potentially dangerous environment’ and ‘lack of financial resources for training courses’ with item ‘lack of adequate staffing’ received the highest score both in this subscale but also in overall MHPSS18. A major stressor in this subscale also found ‘the lack of adequate cover in a potentially dangerous environment’. The organizational structure and processes subscale was the second major source of stress for respondents (11.32; SD=4.60). Lack of managerial support emerged as a major stressor in this subscale. In addition, poor management and supervision was found to be a high stressor in this subscale. Relationship and conflicts with other professionals was the third main source of stress (9.82; SD =3.87).

Respondents reported “workload’ as the fourth main stressor in their working environment. In particular, ‘too many things to do’ and ‘too many different things to do’ were identified as the highest stressors.

In the ‘client related difficulties’ subscale nurses rated ‘the physical threatening patients’ and ‘difficult or demanding patients’ as high stressors for them.

Responses to the self-report stress scale showed that respondents had moderate level of stress similar with the overall score in MHPSS (mean 4.03;SD=1.38). The correlation between MHPSS and the self-report scale showed that there was a significant positive association (r 0.418;p<0.01).

Job satisfaction Scale19

The overall job satisfaction scale revealed that nurses were satisfied with their work (mean 34.2;SD3.4).

Hypotheses

Hypothesis a) There is a negative relationship between occupational stress and a) nurses job satisfaction, b) clinical leadership (team building skills of the head nurse), and c) quality of professional relationships (i) amongst nurses and (ii) between nurses and doctors.

No association was found between stress and collaboration between nurses and doctors and this hypothesis was not supported (r -0.081;NS). However, stress was statistical significantly and negatively associated (r -0.445;p<0.01) with the clinical leadership (team building skills) of the head nurse. This association was significant and the hypothesis was supported. Similarly, there was a negative association but statistically significant (r -0.453;p<0.01) between occupational stress and nurses job satisfaction and this hypothesis was supported. However, the correlation between stress and collaboration amongst nurses was a negative very weak association and not significant (r 0.145;NS). Thus, the hypothesis was not supported.

Hypothesis b) There is a positive relationship between nurses’ job satisfaction and a) clinical leadership, and b) quality of professional relationships (i) amongst nurses and (ii) between nurses and doctors.

The association between job satisfaction and clinical leadership (team building skills of the head nurse) was a positive statistically significant (r 0.418; p<0.05) and stronger than the positive association between job satisfaction and the quality of relationships amongst nurses which was very weak and not significant (r=0.148;NS). The hypothesis between the clinical leadership (team building skills of the head nurse) and job satisfaction was supported, but the hypothesis about job satisfaction and the quality of relationships amongst nurses was not supported since it was not significant. Similarly, no association was found between job satisfaction and collaboration between nurses and doctors (r = 0.069;NS) and this hypothesis was not supported.

Hypothesis c) There is a positive relationship between clinical leadership and professional relationships amongst nurses.

This hypothesis was not supported. The correlation was very weak and not significant (r 0.167;NS).

DISCUSION

Level of occupational stress and stressors in Greek registered mental health and assistant nurses.

In this study the results of MHPSS18 indicate that registered mental health and assistant nurses were experienced moderate level of stress at the time that this investigation took place. This finding is consistent with the scores from the seven-point self - report stress scale used, which showed that nurses reported moderate level of stress as well. These findings contrast those of Jones et al [20]. who found in their study that psychiatric nurses reported high level of stress. However, the different findings between these two studies may be explained by the fact that Jones et al [20]. carried out their study in a very specialized psychiatric hospital with extremely dangerous patients. There are no other empirical studies of the stress levels of mental health nurses working in acute care settings to provide comparative information about whether or not this nursing speciality appears to be stressed, and to what extent. All the other studies have purely described the most frequent stressors reported and/or to demonstrate that mental health nurses were more or less stressed when compared with other nursing specialities or community psychiatric nurses. Nevertheless, the positive and significant association found between the MHPSS [18] and the self-report stress scale validate the interpretation of the findings of both scales.

Mental health and assistant nurses reported that the major source of stress that they encounter in the acute psychiatric care settings was lack of resources. It is worthwhile to note that the item referring to ‘lack of adequate staffing’ was reported to be the highest stressor not only in this subscale but also in overall MHPSS [18]. The reason that the inadequate number of staff perceived as a major stressor is further explained by the second high stressor in this subscale which is ‘lack of adequate cover in a potentially dangerous environment’. However, even though these two stressors refer to the under-staffing level of psychiatric units they must be examined in relation to scores on the 'patients’ difficulties' subscale. In this subscale nurses experienced high stressors from the ‘physical threatening patients’ and ‘difficult or demanding patients’. These findings are fully consistent with Cushway et al’s18 results who found that lack of resources was the major source of stress for mental health nurses, including patients’ related stressors namely ‘physical threatening patients’ and difficulties arising from patients demands. However, even though another study3 found that lack of resources was a major source of stress for mental health nurses, with the high stressors in this subscale relating to hostile patients, surprisingly stated that staff shortages, especially lack of male nurses, created only moderate of stress. Similarly with the findings of the present study other authors [20,21] concluded that contact with potentially threatening patients is one of the major source of stress for mental health nurses. It appears that nurses associate potentially violent patients with lack of resources, including inadequate number of staff to face unpredictable situations [18]. Similarly, Sullivan [7] points out that violent incidents are perceived as increasingly stressful experiences when there is a lack of sufficient manpower resources in acute psychiatric wards to maintain the adequate observation of potentially violent patients.

Lack of financial resources for training courses is also reported as a high stressor in this subscale, and this illustrates the situation in Greece. Due to economic problems, hospitals do not support nurses to attend relevant specialist courses. Furthermore, the fact that a part of respondents in the study were assistant nurses, who have no opportunities to further their studies after their two year basic nursing course, may also explain this finding.

Organizational structure and processes were reported as the second major source of stress which is in consistent with Cushway et al [18]. Lack of managerial support emerged as a major stressor in this subscale which is similar finding with a study found that the majority of psychiatric nurses reported that they do not receive support from managers [7]. Poor management and supervision was found to be a high stressor in this subscale which is explained by the managerial system in Greek hospitals. Head nurses are not necessarily the most qualified nurses in this field. They hold their managerial position mostly as the result of total length of working experience in a state hospital. Thus, their lack of specific knowledge either in management or in mental health nursing renders them unable at times to guide and supervise mental health and assistant nurses who face difficulties in practice.

Relationships and conflicts with other professionals was the third major source of stress that nurses reported in the present study. Difficulties in professional relationships between doctors and nurses and amongst mental health nurses, have been reported as high stressors in nurses' working environment in several studies [1,3,6]. In contrast, Sullivan [7] did not identify professional relationships as main stressors for psychiatric nurses working in acute care setting. However, he acknowledged that when difficulties in psychiatric nurses' professional relationships did occur in their working environment nurses experience high level of stress. In particular, in the present study high stressors in the professional relationships subscale were identified as lack of support from colleagues and conflict with other professionals such as doctors and nurses. In contrast, with the present study Cushway et al [18]. found that professional relationships were not a major source of stress.

Respondents in this study reported workload as fourth source of stress. ‘Too much work to do’, and ‘too many different things to do’ were identified as the highest stressors. The fact that the shortage of nurses has been a serious problem in Greece for the last 10 years justify such results. Mental health and assistant nurses have to work with relatively low nurse: patient ratio. Similarly, another study also found that workload was one of the high stressors for mental health nurses [18].

Client-related difficulties found to be a relatively low source of stress although physically threatening clients/patients and difficult or demanding clients/ patients were reported as high stressors. Similarly, Cushway et al [18]. found that difficulties relating to patients are low source of stress. In contrast, Sullivan [7] pointed out that potential suicide patients, and observation are the most frequent stressors for psychiatric nurses in relation to patients care. However, the fact that the majority of the respondents were specialised in mental health nursing, suggests that nurses were skilled in dealing with patients related problems, hence did not experience undue levels of stress. Similarly, Jones et al [20]. stated that though patient care demands such as supervision may be high, they do not create stress for psychiatric nurses.

Level of job satisfaction in Greek registered mental health and assistant nurses

With respect to overall job satisfaction registered mental health and assistant nurses were satisfied with their job. This result confirms Hale’s [22] conclusion that most of studies on nurses’ job satisfaction show that nurses are satisfied. Similarly, another study found that nurses working in different types of psychiatric units were in general satisfied [11]. However, the former concluded that nurses worked in admission psychiatric ward which is similar with the acute care setting of the present study, were more satisfied compared to long stay wards. This finding is explained by the nature of the work on the acute admission wards. Nurses give intensive care that quickly results in observable patients’ improvements, giving job satisfaction to nurses.

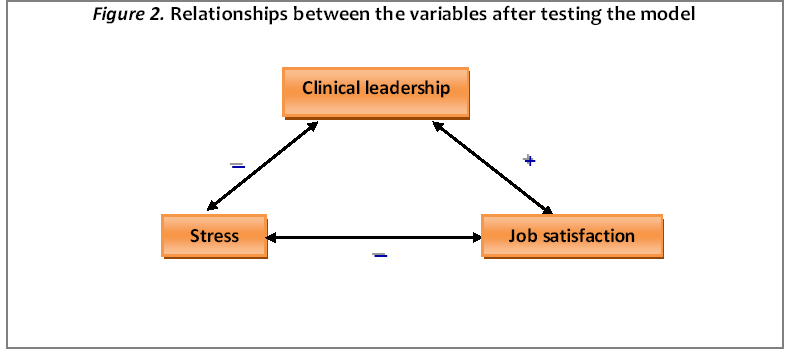

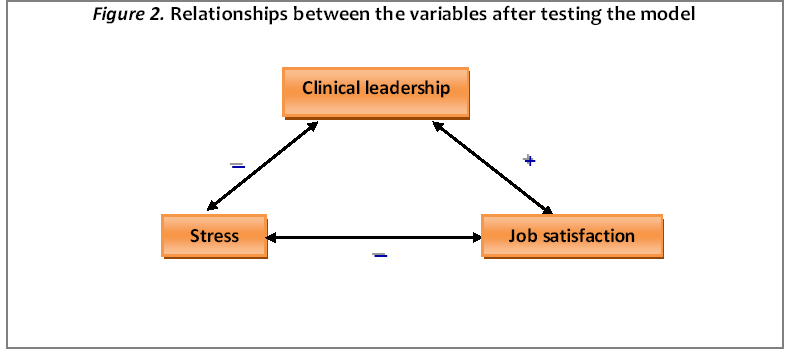

The model reconsidered

The model proposed in figure 1. was not totally supported by the results of this study. In fact, a new model emerged (Fig. 2) as the result of the test of associations proposed in the preliminary model. Collaboration between nurses and doctors was found not to be a determinant factor in the levels of stress or job satisfaction of mental health and assistant nurses. Stronger relationships were found between clinical leadership especially with the team building skills of the head nurse and levels of nurses' stress and job satisfaction. There was also a stronger association and statistically significant found between stress and job satisfaction in mental health and assistant nurses. A weak, not statistically significant association was found between stress, job satisfaction and collaboration amongst nurses. Similarly, was found a weak, not statistically significant, association between clinical leadership (the team building skill of the head nurse) and collaboration amongst nurses. The associations that were not statistically significant are not presented in the model emerged (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Relationships between the variables after testing the model

Relationship between stress and collaboration between nurses and doctors

There is no association found between stress and quality of professional relationships between nurses and doctors. Whilst not reflecting these findings exactly, Trygstad [6] found that relationships between nurses and physicians accounted for only 9% of the stressors identified. Similarly, other researchers also found that relationships with medical staff were rarely reported as source of stress [7,18]. The potential for stress is highlighted by Dawkins et al. [3] in a study where nurses reported difficulties in relationships with doctors. However, 67% of the nurses were in managerial positions, and more likely to have direct dealing with the doctors, and experience stress as a result.

Relationship between stress and quality of relationships amongst nurses

A very weak association and not statistically significant was found between stress and the quality of relationships amongst nurses. This confirms the findings of another study that professional relationships, including those amongst psychiatric nursing peers, might create stress, but only of a low level [18]. However, this very low, non significant, association found in the present study, between stress and the quality of relationships amongst nurses must be accepted with caution. It appears that this association exists by chance, and may be influenced by other factors.

The positive associations between the team building skills of the head nurse and the quality of relationships between nurses might play an important role. Whilst the team building skills of the head nurse have been found to have only a weak, statistically non significant association with nurses’ stress they may influence nurses' stress levels indirectly. However, in the present study it is not possible to accept this weak, statistically non significant association and further investigation is need to clarify the possible association between the team building skills of the head nurse and quality of relationships between nurses.

Relationship between stress and clinical leadership

A negative statistically significant association was found between occupational stress and team building skills of the head nurse. This finding is similar with Trygstad’s6 study in which she found that the head nurse has a pivotal role in resolving problems and conflicts occur amongst the nursing staff. The head nurses’ ability to facilitate the relationships and de-escalate the problems occurring amongst nursing staff are important skills and are particularly helpful in building a cohesive nursing team which does not experience occupational stress [6]. Trygstad [6] pointed out that skilled support of the head nurse is the most effective intervention to resolve work related problems and consequently to increase staff performance. The ability of the head nurse to avoid becoming involved in nurses’ conflicts and to facilitate collaborative practice decrease nurses' stress, since they feel part of a collaborative working nursing team1.

Relationship between stress and job satisfaction

A negative association, and statistically significant was found between stress and job satisfaction. This is in keeping with the results of a number of studies both in mental health and in general nursing [1]. Gray-Toft & Anderson [23] investigated stress in hospital nursing staff and found that stress influenced nurses’ dissatisfaction with their work. The authors concluded that high levels of stress significantly reduced nurses’ job satisfaction. Similarly, Dolan [5] pointed out that burnout was negatively related to psychiatric nurses’ job satisfaction. Furthermore, Cushway et al. [18] supported similar results in their study of mental health nurses from hospital and community settings. Callaghan’s [24] study confirms similar results found for mental health nurses working in acute psychiatric wards.

Relationship between job satisfaction and collaboration between nurses and doctors

There was no association found between job satisfaction and the quality of collaboration between nurses and doctors, which contrast with Eliadi’s [25] finding of a positive relationship between these two variables. However, Eliadi’s [25] findings were derived mostly from nurses working in different specialities, and only 4 psychiatric nurses were included in the sample. For instance, nurses working in an intensive care unit have more interdependent relationships with doctors which might influence nurses’ job satisfaction. In contrast, mental health nurses work more independently than some other specialties, and the resultant nurse-doctor relationship might explain the result of the present study, that collaboration between nurses and doctors is not related to nurses’ job satisfaction. The issue of relationship between job satisfaction and collaboration with nurses and doctors has not been investigated sufficiently in nursing literature, most certainly not in mental health nursing. It has been found that communication with doctors related to nurses’ job satisfaction [12]. However, in a meta-analysis of nurses’ job satisfaction does not include interactions with physicians as a variable, because it was unable to identify a straight forward association between collaboration between nurses and doctors, and job satisfaction [13].

Relationship between job satisfaction and quality of relationship amongst nurses

A very weak, positive, but statistically not significant, association found between job satisfaction and the quality of their relationships amongst mental health and assistant nurses. This low relationship between job satisfaction and quality of relationships amongst nurses has been indirectly supported in a previous conducted research review [1]. Laundeweerd & Boumans [11] found that as mental health nurses work on a one to one basis with the patients there are few opportunities for interactions with, or positive feedback from nursing colleagues. Therefore, relationships and interdependence are not developed to such levels that would affect nurses’ job satisfaction. This aspect was supported by Cronin-Stubbs & Brophy [4] who found that psychiatric nurses received less aid or direct assistance from colleagues, than other specialities in nursing, due to the absence of the necessity of interdependence amongst psychiatric nurses. In addition, from the model tested in the present study it seems that a main source of mental health and assistant nurses' job satisfaction is related to the head nurse rather than to relationships between nurses.

Relationship between job satisfaction and clinical leadership

A positive, and statistically significant association was found between job satisfaction and the team building skills of the head nurse which is in consistent with another study in which they concluded that the first-line managers have an important role in creating a suitable working environment, which provides satisfaction to nurses [26]. In particular, Carson et al. [8] found a strong positive association between supportive line nurse manager and psychiatric nurses’ job satisfaction. Taking into account that mental health nurses reported little impact of the relationships amongst their peers on job satisfaction, it could be suggested that an important influential factor of their satisfaction is the head nurse and his/her ability to build a team. A positively influential head nurse has the charisma to inspire and reward nurses as well as to encourage team working. Furthermore, it has been attested that recognition from the head nurse influences nurses’ job satisfaction [27].

Relationship between clinical leadership and the quality of professional relationships amongst nurses

A very week positive, not statistically significant association was found between the team building skills of the head nurse and the quality of relationships amongst nurses. The role of the ward sister was found to be pivotal in good staff relationships in Trygstad’s study [6]. The author states that the influence of the head nurse influenced levels of friction between staff members, so it can be supposed that positive contributions of the head nurse can build a cooperative nursing team with quality relationships. It is possible that the head nurse has the ability to build a team which is task orientated, within that team the members may have good relationship with the head nurse but not necessary with each other.

CONCLUSION

The present study is one of the first to examine the relationships between inter-professional working, clinical leadership, stress and job satisfaction in mental health and assistant nurses. After testing the preliminary conceptual model, which was devised with variables derived from the literature, a new model emerged with the variables supported by findings from the study.

A significant finding was the influence of the team building skills of the head nurse in decreasing stress and increasing job satisfaction in nurses. In addition, occupational stress was found to decrease nurses' job satisfaction and this finding has been supported in studies in general nursing. Mental health and assistant nurses working in acute care settings were found, that the time of the study carried out, to be experiencing moderate levels of stress. The most frequent sources of stress that nurses reported were lack of resources with the main concern of nurses being lack of adequate staff in relation to potential physical threats from a psychiatric patient. In addition, organizational structure and processes such as lack of support from management and poor supervision were high stressors for participants, as well as relationships and conflicts with other professionals.

The results also show that overall nurses were satisfied with their job. However, the significant findings of this study have allowed identification of specific strategies to decrease occupational stress and to increase mental health nurses' job satisfaction. The determinant factors found to influence stress and job satisfaction may possibly provide some valuable information for hospitals managers about improving the working conditions for mental health and assistant nurses, consequently enabling the provision of better care for psychiatric patients.

Recommendations for future research

Considering that this study tested a preliminary conceptual model it is recommended that future research is needed in order to identify the relationships between inter-professional working, clinical leadership, stress and job satisfaction in Greek registered mental health and assistant nurses.

It is also recommended that in order to avoid difficulties in inference of causality between the variables, longitudinal research design should be used in a future study that would seek to establish the relationships between the variables. Thus, the results of this study could be confirmed and the model further tested.

3638

References

- Nakakis K. and Ouzouni Chr. Factors influencing stress and job satisfaction of nurses working in psychiatric units. Health Science Journal 2008, 2 (4): 183-195.

- Wheeler H.H. A review of nurse occupational stress research: 1. British Journal of Nursing 1997, 6 (11): 642- 645.

- Dawkins E. J., Depp F.L. and Selzer E.N. (1985). Stress and the psychiatric nurse. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing 1985, 23 (11): 9-15.

- Cronin - Stubbs D. and Brophy E. B. Burnout: can social support save the psychiatric nurses? Journal of Psychosocial Nursing in Mental Health Services 1985, 23: 8-13.

- Dolan, N. The relationship between burnout and job satisfaction in nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1987, 12: 3-12.

- Trygstad, L. N. Stress and coping in psychiatric nursing. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing 1986, 24 (10): 23-27.

- Sullivan, J. P. Occupational stress in psychiatric nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1993, 18: 591-601.

- Carson, J., Fagin, L., and Ritter, S. A. Stress and Coping in Mental Health Nursing. London, Chapman and Hall, 1995.

- Kipping C.J. Stress in mental health nursing. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2000, 37: 207-218.

- Robinson J.R, Clements K. and Land C. Workplace stress among psychiatric nurses. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing, 2003, 41(4): 32-41.

- Landeweerd, J. A. and Boumans, N. P. G. Nurses’ work satisfaction and feeling of health and stress in three psychiatric departments. International Journal of Nursing Studies 1988, 25 (3): 225 - 234.

- Sammut, G. R. Psychiatric nurses' satisfaction: the effects of closure of a hospital. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1997, 26: 20-24.

- Blegen, M. A. Nurses’ job satisfaction: a meta-analysis of related variables. Nursing Research 1993, 42: 36-41.

- Floyd, G. J. Psychiatric Nursing Aides. Nursing Management 1983, 14 (9): 36-40.

- Farrel G.A. and Dares G. Nursing staff satisfaction on a mental health unit. Australian and New Zealand of Mental Health Nursing 1999, 8: 51-57.

- Bowling A. Research methods in health. 2nd edition, New York, Open University Press, 2007.

- Brink P J and Wood A J Advanced Design in Nursing Research. London, Sage Publications, 1998.

- Cushway, D., Tyler, P. A., and Nolan, P. Development of stress scale for mental health professional. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 1996, 35 (2): 279-295.

- Adams A. and Bond S. Nursing Organisation on Acute Care: the Development of Scales. Report no 71. Newcastle: Centre for Health Services Research University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 1995.

- Jones JG. Stress in Psychiatric Nursing. In Payne R. and Firth-Cozens J (eds) Stress in Health Professionals. Liverpool, John Wiley and Sons ltd, 1987.

- Travers C., Firth-Cozens J. Experiences of Mental Health Work. Hospital Closure, Stress and Social Support. Paper presented at the British Psychological Society, Annual Occupational Psychology Conference. Bowness-on-Windermere, 1989.

- Hale C. Measuring job satisfaction. Nursing Times, 1986, 82 (5): 43-46.

- Gray-Toft P. and Anderson J. Stress among hospital nursing staff: its causes and effects. Social Science and Medicine, 1981, 15A: 639-647.

- Callaghan P. Organization and stress among mental health nurses. Nursing Times, 1991, 87 (34): 50.

- Eliadi, C.A. Nurse-physician collaboration and its relationship to nurse job stress and job satisfaction. University of Massachusetts: Doctoral Dissertation, 1990.

- Gillies D.A, Franklin M., Child D. Relationship between organizational climate and job satisfaction of nursing personnel. Nursing Administration Quartely, 1990, 14 (4): 15-22.

- Swansburg R.C. and Swansburg R. J. Introductory Management and Leadership for Nurses. USA, Jones and Battlett Publishers,1999.