Keywords

childhood vaccination uptake, urban vaccination rates, attitudes, socioeconomic, Greece

Introduction

Vaccination is an undoubtedly effective, broadly accepted preventive measure reducing morbidity and mortality caused by infectious agents, constituting the solid ground of prevention of distinct infectious diseases in childhood as well. Among the preventive measures, vaccination is of major importance in the primary health care of children, rendering the active immunization of adults of limited importance [1].

The development of biotechnology was followed by optimized techniques and acceleration of the development of optimal vaccines with longer viability. Subsequently, the implementation of several vaccination programs was assessed, and weaknesses were detected and highlighted [1].

The epidemiology of vaccine preventable diseases has been modified by the development and implementation of vaccination programs [1,2], i.e., measles, mumps, rubella, and hepatitis B exhibit a decreasing trend of morbidity, but the suboptimal vaccination rates constitute an important component of the health care debate worldwide [3-7]. Several socioeconomic factors and structural barriers have been incriminated for low immunization rates [8-13]. Social determinants such as young age of parents, low level of parental education, birth order of the child [14,15], financial barriers such as low family income, lack of health insurance and gaps in the relevant infrastructures such as lack of periodic primary health care access, or decreased availability of health care facilities [8-13], have been found to be associated with low immunization rates, in various geographically confined areas, without generalizable results. The role of the parents’ perceptions regarding the difficulty to access health services, health beliefs and attitudes toward childhood immunization, is a controversial issue, as distinct studies [16-18] have identified these as risk factors for decreased vaccination coverage, whereas others [19,20] suggest that socioeconomic factors play a more important role, and a recent study [21] proved that parents’ beliefs may simply reflect their sociodemographic characteristics imposing the latter of principal, undisputable importance.

The need for a survey in the distinct cultural factors of Athens in Greece was imperative. In Greece, the introduction of the personal child health record for children in 1976, proved to be an important subsidiary in the recording of personal health data during infancy, preschool and school age [22]. The vaccines included in the National Vaccination Programme are provided free of charge to all residents including immigrants, in primary health centres or health care facilities.

This study attempted to assess the vaccine coverage of preschool and primary school children in Athens, Greece, highlight weaknesses, identify gaps in the primary health care of these age groups, and assess the potential effect of the parental attitudes and beliefs towards immunization, socioeconomic characteristics of the family and perceived barriers to access health care facilities, with the compliance to recommended immunization, and vaccination status of children.

Material and Methods

Three hundred and four children 0-12 years old attending day care units and primary schools of six distinct areas in Athens, Greece, were registered. This population was selected to be representative of the urban population of Athens via the application of a stratified selection initially among all municipalities and then among day care units and primary schools within each selected municipality. The Child vaccination booklet was used to gather information regarding vaccination status, and a self-administered questionnaire addressed to parents and other supervisors illustrated the age, order of birth and number of siblings of each registered child, the age, job, educational status, family status of parents (socioeconomic characteristics), family composition, identification of the person supervising vaccinations, insurance company, level and origin of education regarding vaccines, the beliefs and attitudes regarding the performance of immunization, and perceived barriers to vaccination. In the Questionnaire the factors tested as to whether they facilitate vaccinations were: vaccinations administered in school settings, vaccination conducted by public health officials at home, appointment arranged by and vaccination administered at public health services. The epidemiologic data were presented according to the descriptive epidemiology and the statistical analysis was performed with the method of x2 test for probable correlation of vaccine coverage with several variables.

Definition

Full vaccination status: Children were considered fully vaccinated if they had received all the following vaccinations according to the National Vaccination Program: (a) 5 doses of DTP vaccine, (b) 5 doses of poliomyelitis vaccine, (c) 2 doses of MMR vaccine, (d) 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine, (e) measles, (f) mumps and (g) rubella vaccines, available at that time, if they had received one dose, at the age of >12 months, and the booster at the age> 10 years, and (h) 4 doses for Haemophilus Infuenza type b (Hib) if the first dose was administered at the age of 0-6 months and the 4th at the age of >12 months; alternatively for Hib, 3 doses if vaccination began at the age of 7-11 months and the 3rd dose was administered at the age of >12 months, or 2 doses if the first dose was administered at the age of 12-14 months or 1 dose if Hib vaccination was administered at the age of > 15 months.

Results

All 304 children, 155 males and 149 females had personal child health record.

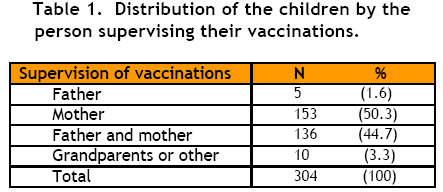

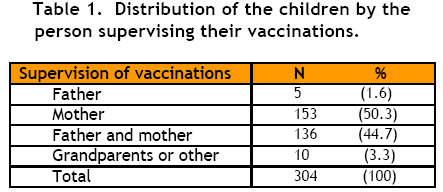

The supervision of vaccinations was performed by both parents in 44.7% (136), by mother alone in 50.3% (153), by father alone in 1.6% (5), by grandparents or other person in 3.3% of children (Table 1).

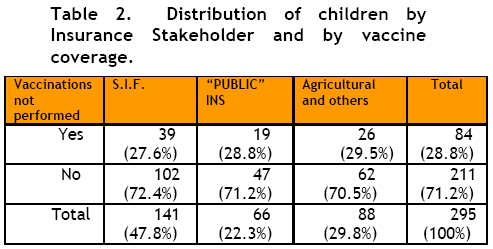

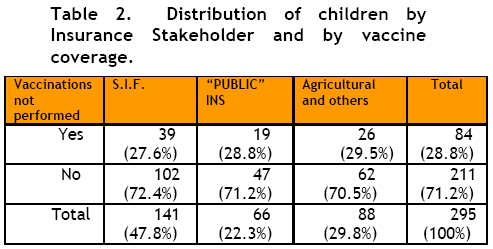

The Insurance Stakeholder was in 47.8% (141) the Social Insurance Foundation (S.I.F.), covering workers of private enterprises, in 22.3% (66) the “Public” insurance, covering workers of the public sector and in 29.8% (88) the “Agricultural Insurance” covering owners and workers of agricultural and the farming industry, with varying vaccination coverage (Table 2).

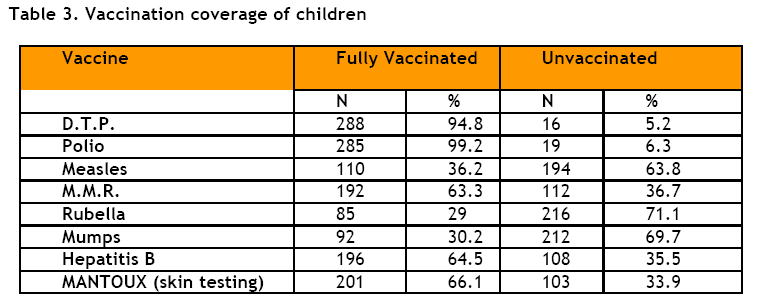

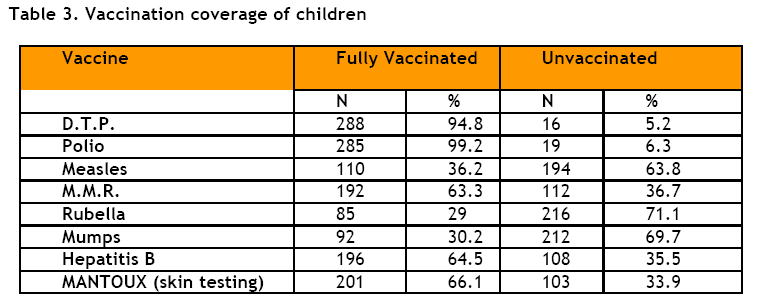

Among registered children 94.8% (288) were fully immunized with D.T.P. (Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis), 99.2% (285) with the polio vaccine, 63.3% (192) with Μ.Μ.R, additionally to 36.2% (110) were immunized against measles, 30.2% (92) against mumps, 29% (85) against rubella, mounting to a vaccination coverage equal to 99.5% for measles, 93.5% for mumps, and 92.3% for rubella, and 64.5% for the newly introduced Hepatitis B. The vaccine against Hepatitis B is well accepted by parents. A minority of 26.3% (80) were immunized against TBC (Table 3).

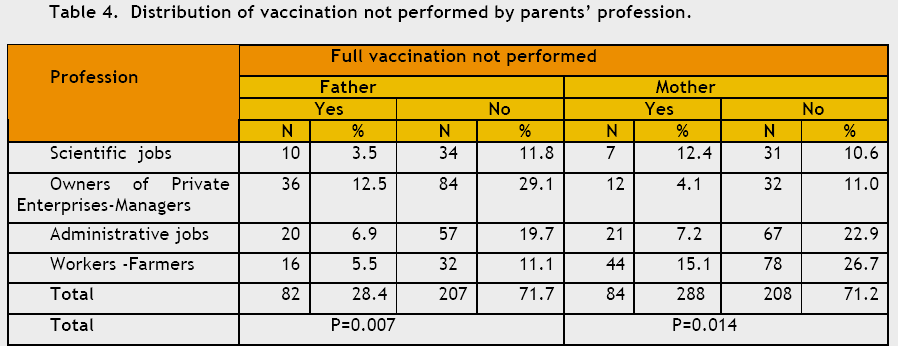

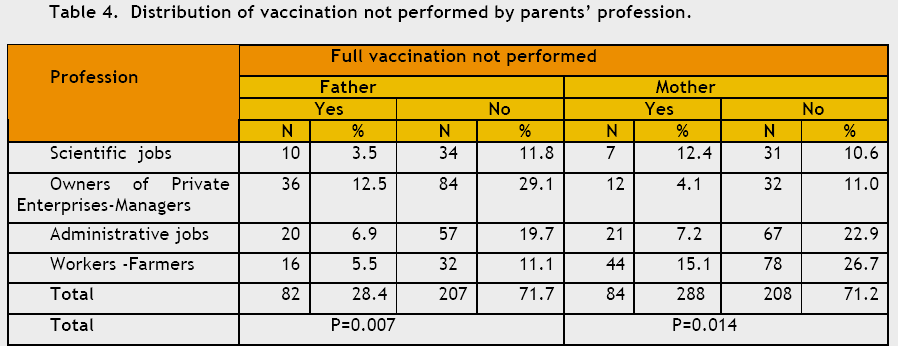

The immunization rate with each vaccine did not correlate with the educational level of the parents, the order of birth of the child, the person supervising the vaccination program of the child, the insurance stakeholder, or the region of residence (P≅0.06-0.99). Parents with scientific responsibilities, working in clerical jobs and those in medium level of private sector exhibited higher rates of vaccination of their offspring, compared to parents owning enterprises of the private sector, or heading Departments, or farmers and workers; revealing the usefulness of shorter working hours in the accomplishment of the public health responsibilities, (P=0.007 for father, and P=0.014 for mother) (Table 4). Additionally, vaccination uptake was correlated to the adequacy of education of parents about vaccinations (P=0.01). Among all parents, 16.25% explained that their offspring were unvaccinated as a result of badly organized family program.

The opinions of parents/guardians regarding the factors which would facilitate the vaccination of children were similar among parents of different educational levels, among all groups of supervisors, among all insurance stakeholders, independent of the degree to which they believe they are educated about vaccinations, and the region (P≅0.06-0.97). On the other hand their opinions vary according to the job of the parents (P=0.007) for the father and P=0.014 for the mother). Among all parents 51.8% suggested that the school based vaccination performance would facilitate the process and it would optimize the vaccination coverage.

Discussion

It is important to highlight that in Greece immunization of boys and girls aged 1 year with the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine was introduced in the mid-1970s, without policies to attain high vaccination coverage and to protect young adolescents and young women. The vaccination of children against vaccine preventable diseases interrupts their transmission, reduces their incidence rate, and increases the age at which the non-immunized people get the infection [23]. Although this is a protection for the population, regarding rubella, it has been speculated that if vaccination coverage is low in the 1 year olds, this shift of age at infection can increase rubella incidence among older age groups, including childbearing women, with subsequent increase in congenital rubella [24]. Thus, in 1993, occurred a major rubella epidemic, affecting women of childbearing age, followed by the birth of the largest number of babies with congenital rubella syndrome ever recorded in Greece, highlighting the critical role of vaccine coverage for public health [23]. As a result, a comprehensive policy has been introduced in Greece for the prevention of this phenomenon with the immunization of young adults and childbearing age women, as well with systematic measures to sustain high vaccination coverage and complete vaccination of children and adolescents with the appropriate booster doses [23].

This study highlights the highest level of vaccine coverage of children of preschool age in Athens. The percentage of vaccinated was 94.8% for D.T.P., 99.2% for poliomyelitis, 63.3% for M.M.R. additionally to 36.2% for measles, 29% for rubella, and 30.2% for mumps, mounting to a vaccination coverage equal to 99.5% for measles, 93.5% for mumps, and 92.3% for rubella, and 64.5% for the newly introduced Hepatitis B. These rates are higher than those identified in other studies concerning the Greek population [25-30] especially when compared to rural areas [31-33]. The immunization coverage of schoolchildren was inadequate in three primary health care areas in rural Crete, Greece [32]. A school based immunization survey was conducted to identify the vaccination coverage against diphtheria and tetanus as high as 82%, for mumps 75.6% and 36.3% and for rubella 74.7% and 32% in primary and secondary school age children respectively [32].

Additionally to the job, unvaccinated status depends on the degree of parental education on the issue of vaccinations. The level of vaccination coverage does not depend upon the educational status, the order of birth of the child or the Insurance stakeholder of the parents, whereas it depends on the professional status of both the father and the mother, with a P= 0.007 and P=0.014 respectively, the latter being consistent with findings of a previous study [34]. Parents with scientific responsibilities, working in clerical jobs and those in medium level of private sector exhibited higher rates of vaccination of their offspring, compared to parents owning enterprises of the private sector, or heading Departments, or farmers and workers; revealing the usefulness of shorter working hours in the accomplishment of the public health responsibilities. Other studies, unlike the current paper, indicated that the rates of vaccine coverage depend upon the educational status of the parents [35].

The opinions of parents/guardians regarding the factors which would facilitate the vaccination of children were similar among parents of different educational levels, among all groups of supervisors, among all insurance stakeholders, independent of the degree to which they believe they are educated about vaccinations, and the region (P≅0.06-0.97). On the other hand their opinions vary according to the job of the parents (P=0.007 for the father and P=0.014 for the mother).

Our findings are consistent with those of a cross-sectional study among the 6 year old school children in Greece [36]. The predictors of low childhood vaccination uptake in the latter were defined as the minority groups, especially Roma and immigrants, families with many children, young mother, and household headed by fathers with low educational level possibly reflecting minor education on the issue of vaccinations and an occupational status without scientific responsibilities, different from clerical jobs and those in medium level of private sector 36. The parental attitude on immunization affected the immunization-seeking behavior to a less extended degree, setting the low socioeconomic status as a high risk factor of major importance in the vaccine coverage in Greece 36. The distance from the immunization location and the perceived severity of disease are important determinants of vaccination status among the age group of 6 year old school children [36].

In 2006 in northern Greece the vaccination rate against rubella was 91.7% and 94.7% in the 16 months – 5 years and 6-10 years age groups respectively [31]. In 2005 the vaccination coverage in a sample of adolescents aged 15-19 attending 12 senior high schools in four provinces in northern and southern Greece indicated high rates of under vaccinated adolescents, mainly due to non-compliance to the booster dose of Td and MMR [33]. The rates of full vaccination for measles, mumps and rubella were 65.0%, 56.0%, 57.6%, respectively, 94.2% for poliomyelitis, 78.4% for hepatitis B, 77.4% for BCG, 65% for tetanus, and 54.4% for diphtheria. Immigration from former Soviet Union where diphtheria outbreaks were recorded recently, to Greece, imposes a significant risk of resurgence of the disease in Greece [37]. The importance of adolescent boosters for tetanus and diphtheria is well recognized [33] and the middle school vaccination law in the US which has been followed by increased vaccination coverage among adolescents [38], should be considered for Greece as well.

Conclusions

Unvaccinated status depends on the degree of parental education on the issue of vaccinations and on their job.

The opinions of parents/guardians regarding the factors which would facilitate the vaccination of children were similar among parents of different educational levels, among all groups of supervisors, among all insurance stakeholders, independent of the degree to which they believe they are educated about vaccinations, and the region. On the other hand their opinions vary according to the job of the parents.

The immunization rate identified in this study was very high for an urban population. These rates are higher than those identified in other studies concerning the Greek population especially when compared to rural areas.

Particularly in view of the recent adverse publicity regarding the safety of various vaccinations, in several European countries, it is of crucial importance to keep this high urban vaccination uptake and expand it to rural areas of Greece.

There is a need for competent surveillance systems for vaccine preventable diseases, and congenital rubella syndrome, which accompanied by other critical measures would aim at the evaluation of the immunization programmes.

Further enhancement of vaccination uptake by appointment in public health services, or school based vaccination, close monitoring of disease incidence and vaccination coverage, and consideration upon middle school vaccination are deemed as imperative especially under the current rapidly changing socioeconomic circumstances in Greece.

3581

References

- Trichopoulos D. The Check-up. Archives of Hygiene 1980; 50 (29): 9-12. (Greek)

- Peter G. Active and passive immunization. Report of the Committee of Infectious Disease. 22nd ed. Illinois: Elk Grove Village. American Academy of Pediatrics 1991; 7-66.

- WHO. Expanded programme on immunization. In: The EPI Coverage Survey, training for Mid-level managers. WHO; 1991 [WHO/EPI/MLM/91.10].

- Impact of vaccines universally recommended for children-United States, 1990?1998.MMWR 1999; 48:243-248.

- Bedford H, Elliman D. Concerns about immunization. BMJ 2000; 320 (7229):240-3.

- GIVS: Global Immunization Vision and Strategy 2006-20151.Geneva: WHO/UNICEF; 2005. Available from: https://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2005/WHO_IVB_05.05.pdf

- Rodewald LE, Szilagyi PG, Shiuh T, Humiston SG, LeBaron C, Hall CB. Is underimmunization a marker for insufficient utilization of preventive and primary care? Arch Pediartr Adolesc Med 1995; 149 (4):393-397.

- Swennen B, Van Damme P, Vellinga A, Coppieters Y, Depoorter AM. Analysis of factors influencing vaccine uptake: perspectives from Belgium. Vaccine 2001; 20:S5?7.

- Zucs AP, Crispin A, Eckl E, Weitkunat R, Schlipkoter U. Risk factors for undervaccination against measles in a large sample of preschool children from rural Bavaria. Infection 2004; 32(3):127?33.

- Rosenthal J, Rodewald L, McCauley M, Bermans S, Irigoyen M, Sawyer M, et al. Immunization coverage levels among 19- to 35-monthold children in 4 diverse, medically underserved areas of the United States. Pediatrics 2004; 113(4):E296?302.

- O'Connor KS, Bramlett MD. Vaccination coverage by special health care needs status in young children. Pediatrics 2008 Apr; 121(4):e768-74.

- Bates AS, Wolinsky FD. Personal, financial, and structural barriers to immunization in socioeconomically disadvantaged urban children. Pediatrics 1998 Apr; 101(4Pt1):591?596.

- Wood D, Donald-Sherbourne C, Halfon N, Tucker MB, Ortiz V, Hamlin JS, Duan N, Mazel RM, Grabowsky M, Brunell P, et al. Factors related to immunization status among inner-city Latino and African-American preschoolers. Pediatrics 1995 Aug; 96(2 Pt 1):295-301.

- Luman ET, McCauley MM, Shefer A, Chu SY. Maternal characteristics associated with vaccination of young children. Pediatrics 2003; 111(5):1215?8.

- Kim SS, Frimpong JA, Rivers PA, Kronenfeld JJ. Effects of maternal and provider characteristics on up-to-date immunization status of children aged 19 to 35 months. Am J Public Health 2007 Feb; 97(2):259-66. Epub 2006 Dec 28.

- Santoli JM, Szilagyi PG, Rodewald LE. Barriers to immunization and missed opportunities. Pediatr Ann 1998; 27 (6):366?374.

- Kimmel SR, Madlon-Kay DJ, Burns IT, Admire JB. Breaking the barriers to childhood immunization. Am Fam Physician. 1996; 53 (1):1648?1656.

- Brenner RA, Simons-Morton BG, Bhaskar B, Das A, Clemens JD; NIH-D.C. Prevalence and predictors of immunization among inner-city infants: a birth cohort study. Pediatrics 2001; 108 (3):661?670.

- Poggas N, Vlassis T, Babatsikou F, Koutis Ch. Immunity to Rubella virus in urban population of Athens. Medical Annals 1994; 17(12):613-615. (Greek)

- Strobino D, Keane V, Holt E, Hughart N, Guyer B. Parental attitudes do not explain underimmunization. Pediatrics 1996; 98 (6Pt1):1076?1083.

- Prislin R, Dyer JA, Blakely CH, Johnson CD. Immunization status and sociodemographic characteristics: the mediating role of beliefs, attitudes, and perceived control. Am J Public Health 1998 December; 88(12): 1821?1826.

- Marangos Ch, Valassi Adam E, Manolakis G, Manolaki A. Personal child health record. Application and Usefulness. Hippocrates 1982; 10 (2):83-89. (Greek)

- Panagiotopoulos T, Antoniadou I, Valassi-Adam E. Increase in congenital rubella occurrence after immunization in Greece: retrospective survey and systematic review. BMJ 1999; 319 (7223):1462-1466.

- Bart KJ, Orenstein WA, Preblud SR, Hinman AR. Universal immunization to interrupt rubella. Rev Infect Dis 1985; 7 (suppl 1):177-184S.

- Siachanidou T, Drakonaki S, Garoufi A. Vaccine coverage in hospitalized child population. Pediatrics 1993; 56:503-510. (Greek)

- Apostolides G, Ellinas D, Labropoulou Ch. Vaccine coverage of students of the 1st and sixth class of High School in Thassos island. Pediatrics 1991; 54:337-344. (Greek)

- Livadas N, Delissavas M, Karagianopoulou M, Karagiannopoulou N, Adam G. Vaccine coverage of school students in Rafina area Athens. Pediatrics 1989; 52:274-282. (Greek)

- Marangos Ch, Papadeas D, Antoniadou I, Valassi-Adam E. Vaccinations 1988. Archives of Hellenic Medicine 1989; 6:140-142. (Greek)

- Chadjipandelis S. Epidemiologic investigation of the vaccination against Polio, Measles, Diptheria Tetanus Pertussis or Diptheria Tetanus, or Smallpox in 3,000 primary school students in Thessaloniki. School Hygiene 1977; 38:107-111. (Greek)

- Chadjipandelis S. Chrisochoou-Dalessi Z. Vaccination coverage. Pediatrics 1982; 45: 201-205. (Greek)

- Gioula G, Fylaktou A, Exindari M, Atmatzidis G, Chatzidimitriou D, Melidou A, Kyriazopoulou-Dalaina V. Rubella immunity and vaccination coverage of the population of Northern Greece in 2006. Eurosurveillance 2007;12 (11). Available from: https://www.eurosurveillance.org/em/v12n11/1211-225.asp.

- Lionis Ch, Chatziarsenis M, Antonakis N, Gianoulis Y, Fioretos M. Assessment of vaccine coverage of schoolchildren in three primary health care areas in rural Crete, Greece. Family Practice 1998; 15(5):443-448.

- Bitsori M, Ntokos M, Kontarakis N, Sianava O, Ntouros T, Galanakis E. Vaccination coverage among adolescents in certain provinces of Greece. Acta Paediatrica 2005; 94:1122-1125.

- Babatsikou F, Georgiou V, Vardaki Z, Bellia Ch, Kokkinakis S, Ktenas E, Koutis Ch. Vaccination coverage of preschool children in Attica. 2nd Hellenic Congress on Public Health and Health Services, Athens, 1998. (Greek)

- Orenstein WA, Atkinson W, Mason D, Bernier RH. Barriers to vaccinating preschool children. J. Health Care Poor Undeserved 1990, 1: 315-330.

- Danis K, Georgakopoulou T, Stavrou T, Laggas D, Panagiotopoulos T. Predictors of childhood vaccination uptake: a cross-sectional study in Greece. Vaccine 2010; 28(7):1861-1869.

- Escola J, Lumio J, Vuolpio-Varkila J. Resurgent Diphtheria-are we safe? Br Med Bull 1998; 54:635-645.

- Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Effectiveness of a middle school vaccination law-California, 1999-2001. MMWR 2001; 50:660-3.