Keywords

Infection prevention; Standard precaution; Healthcare-associated infection

Abbreviations: AOR: Adjusted Odds Ration; CASH: Clean and Safe Health Facility; COR: Crude Odds Ration; CI: Confidence Interval; HAI: Healthcare Acquired Infection; IPC: Infection Prevention and Control

Introduction

Healthcare Associated Infections (HAIs) are alarming public health problems worldwide. A hundreds of millions of patients suffered from them while a heavy toll was recorded in low- and middle-income countries [1-3]. HAI results in prolonged hospital stay, long-term disability, increased drug resistance microbes, high costs, and excess deaths [4,5]. However, by applying well proven and low-cost infection prevention and control (IPC) measures possible to halt the burden of HAI at least by 30% [6].

Hence, establishing IPC measures is an effective means to reduce transmission of HAIs to patients, visitors, and employees. The core components of IPC are hand hygiene, personal protective equipment, sterilization and disinfection of instruments, safe disposal of wastes, sharps, and handling soiled linen. Besides these, personal health and safety education, immunization programs, and post-exposure prophylaxis are part of IPC measures [7-9].

Despite the availability of these inexpensive IPC strategies, compliance with standard infection control practices remains very low, mostly in low-income and middle-income countries [10]. Because of this, Healthcare workers (HCWs) are at increased risk of occupationally acquired infections transmitted from contact, droplet, airborne and inanimate vehicle-based pathogens and also true for their patients [11-13].

Unsafe injection practices ensued about 66,000 hepatitis B, 16,000 hepatitis C and 1000 human immunodeficiency virus infections annually [14]. As the result of these 1100 deaths and disability happen to health workforce [15]. Over 90% of these infections occurred in the resource limited countries, mostly in Africa, where infection is more rampant and adherence to standard precautions can be poor [16]. In addition, 15% of healthcare wastes are considered hazardous and contribute to this problem [17].

Thus, to grantee compliance with infection prevention practices depends on knowing the extent and severity of the problem but only few studies done on this issue especially in the developing countries [1,18].

Few studies done in the hospitals of Ethiopia reported that 65% of health workers had good compliance to infection prevention guideline in Dawuro [19] while only 15% Hadiya [20]. Moreover, a good infection prevention practice was 66.1% in Addis Ababa [21] and 60.5% in Otona hospital [22]. Similarly, it was 48.35% in Dubti hospital [23] and 38.8% in Shenen Gibe hospital [24]. Good knowledge on infection prevention was mentioned by 50.6% and 99.3% in Dubti [23] and Otona hospital [22], respectively.

Furthermore, adherence to hand hygiene was poorly low particularly in developing countries like Ethiopia, which was only 48.7% of health workers compliant on average [25]. Similar findings reported that compliance to hand hygiene was 61% in general hospital of Zambia [26] and only 16.5% Hospital of Gondar University [27]. Likewise, 51.4% of health professionals were always practiced hand washing in Abet hospital of Addis Ababa [21]. Appropriate health care waste management was stated only by 31.5% of health workers in health facilities of Gondar [28].

From these empirical evidences, there is a wide discrepancy on the adherence to infection prevention and most of them are only limited to a single study area, which might pose difficulty for policy makers, health planners and managers to make evidence-based decisions.

On top of this government of Ethiopia has been implementing strategies to increase patient safety and quality of care for patients, companions and health workforce by designing different policy guides. Among these, Ethiopian hospital reform provides overall policy directives [7], and also IPC guide illustrates detail procedures of infection control practices [8]. In comparable to this, Clean and Safe Health Facilities (CASH) has been executing to reduce HAIs and make hospitals safer place since 2014 [29].

Though these efforts are in place, adherence of health professionals to these policy directives and their effectiveness are not well-know yet. Therefore, the aim of this study was to measure health professionals’ compliance to infection prevention procedures and its associated factors in all public hospitals of Kambeta Tembaro zone.

Method and Materials

Study area and design

Facility based cross-sectional study design was employed from March, 01-April 30/2019 in Kembata Tembaro zone, which is located 315 km far from Addis Ababa. There are one general hospital, three primary hospitals, 35 health centers, and 160 health posts with a total of 908 health professions. Of a total of health professionals, 498 are serving in the four public hospitals of the zone.

Population

The source population comprised all health professionals, who are currently working in the four public hospitals of kembata- Tembaro zone. Whereas, the study population was sampled health professionals, who have direct contact with patients, body fluid, specimen and medical devices in the study area and presented during data collection period.

Sample size determination

A single population proportion formula was used to determine sample size with the following assumptions: Proportion of health professionals comply with infection prevention practice (P=0.54) in the study done in Bahir-Dar, Ethiopia [30], using 95% confidence interval (Z=1.96) and margin of error (d=0.05). After adding 5% (19 health professionals) for potential non-response, the final sample size was 401 health professionals.

Sampling procedure

The sample size was allocated using proportional allocation to size of number of professionals in respective hospitals. Finally, simple random sampling was employed to select study participants by their name using computer-generated random numbers in Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, 2016) from the sampling frame.

Study variables and measurement

Dependent variable was compliance of health professionals with infection prevention practices. Whereas independent variables were included socio-demographic (sex, age, educational level, working hours per week, type of profession, marital status, work experience), health facility related factors (availability of guideline, familiarity with guideline, training status, and immunization status) and knowledge status of health providers.

Compliance towards standard precautions was assessed in four domains (adherence to hand hygiene, personal protective equipment, safe injection practice and sharp waste management). The overall compliance to infection prevention among health professionals was measured by using ten items through “yes” or “no” questions. For analysis purpose scoring system was done in which the respondent’s “yes” and “no” answers provided for the questions were allocated “1” or “0” points, respectively. Compliance to infection prevention scores were summed up to give a total compliance score for each health professional. Thus, total score of infection prevention questions ranging from 0 to 10 were classified into two categories of response: good compliance (if above the mean) and poor compliance (if equal to or below the mean) [30-32].

The health professionals’ knowledge regarding infection prevention was measured by ten items with “yes” and “no” options. To get their knowledge status, similar processes were followed a score of 1 was assigned for each correct answer and 0 for incorrect answer; hence the total score of knowledge items ranges from 0 to 10. Consequently, knowledge of health professionals on infection prevention was classified into two categories: Knowledgeable (if above the mean) and not knowledgeable (equal to or below the mean) [30-32].

Development of data collection tools

The questionnaire for data collection was developed based on recent Ethiopian hospital service transformation guideline [33] and by reviewing other published articles [19,21,32]. This questionnaire had contained four parts: socio-demographic, health facility related factors, knowledge and infection prevention practice of health professionals in the public hospitals.

Data collection procedure: The primary data used for this study was collected using a semi-structured self-administered questionnaire assisted by facilitators for clarification purposes. To facilitate data collection process four data collectors who hold a bachelor of health science and one supervisor who has a master’s degree in public health were assigned to monitor quality of collected data on daily bases.

Data quality management: The questionnaire for survey was first prepared in English language, then translated into Amharic and back translated into English to check for consistency. Training was given for one day for the data collectors and supervisor. Pre-test was conducted by taking 5% of the total sample size (19 health professionals) before the actual data collection period and proper modification was done on the questionnaire based on the feedback. Every day after data collection, questionnaires were reviewed and checked for completeness by supervisor.

Data analysis procedure: Data were coded and entered into Epi data version 3.1 and transported into version 23.0 for analysis. After cleaning data for inconsistencies and missing values in SPSS, descriptive statistics such as mean, median, frequency and proportion were done. Bivariate analysis using binary logistic regression was done and all independent variables that had an association with the outcome variable at p-value of 0.25 were selected for multivariate analysis. Then multivariate analysis using enter method was done to determine presence of statistically significant association between independent variables and the outcome variable at p value <0.05 and/or AOR with 95% CI. The results were presented in the form of tables, figures and text using frequencies and summary statistics.

Ethical clearness: Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institution Review Broad (IRB) of Institute of Health, Jimma University. Formal letter of permission was obtained from zonal health department to the respective districts. Informed verbal consent of the study participants was obtained prior to interview by explaining the purpose of the study. Confidentiality of their information was assured by using a coding system and by removing any personal identifiers. The right of respondents to refuse to answer for few or all of the questions was respected.

Results

Description of study participation

Out of 401 sampled health professionals, 391 were participated in this study, which provided the response rate of 97.9%. More than half of respondents (204, 52.2%) were male by their sex and 201(49.9%) were between age range of 30-39 years old. The majority of the respondents (215, 55%) were married and 250(63.9%) were nurses by their profession. Regarding to their experience, 191(48.8%) had served for less than 5 years. Three hundred sixty-one (92.3%) were worked above 40 hours per week and 329(84.1) of participants were first degree holders (Table 1).

| Variable (n=391) |

Frequency |

percentage |

| Sex |

Male |

204 |

52.2 |

| Female |

187 |

47.8 |

| Age category |

<30 |

190 |

48.6 |

| 30-39 |

201 |

49.9 |

| 40-49 |

6 |

1.5 |

| Marital status |

Married |

215 |

55 |

| Single |

152 |

38.9 |

| Divorced |

10 |

2.6 |

| Widowed |

14 |

3.6 |

| Category of health professions |

Nurse |

251 |

64.2 |

| Doctor |

82 |

21 |

| midwife |

52 |

13.3 |

| Laboratory technicians |

6 |

1.5 |

| Service year |

<5years |

171 |

43.7 |

| 5-9 years |

198 |

50.6 |

| 10-14 years |

22 |

5.7 |

| Hours worked per week |

Less than 40 |

9 |

2.3 |

| 40 hours |

21 |

5.4 |

| Above 40 |

361 |

92.3 |

| Educational level |

Diploma |

71 |

18.2 |

| First degree |

281 |

71.9 |

| Second degree and above |

39 |

10 |

Table 1 Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents, among health professionals in public hospitals of kembata Tembaro zone, South Ethiopia, 2019.

Health Facility related variables

Of the total respondents, 373 (95.4%) knew that the presence of infection prevention guidelines and 352(94.3%) were familiar with these guidelines. Majority of study subjects, (293,74.9%) have taken part in any training program about infection prevention or standard precautions in the last one year. The majority of the participants, 361 (92.3%) were vaccinated for hepatitis B virus and the remaining 30(7.7%) were not vaccinated. The reason for not vaccinated, 18(4.6%) participants were not aware about necessity of vaccine and 12(3.1%) of participants stated that there was no HBV vaccine in the facilities (Table 2).

| Variables (n=391) |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| Availability of infection prevention guideline in the hospital |

Yes |

373 |

95.4 |

| Familiarity with this guideline |

Yes |

352 |

94.3 |

| Training status on the standard precaution in last one year |

Yes |

293 |

74.9 |

| Vaccinated for Hepatitis B virus |

Yes |

361 |

92.3 |

| Reasons for not vaccinated |

Lack of awareness on vaccine |

18 |

4.6 |

| Unavailability of anti-gene |

12 |

3.1 |

Table 2 Health facility related variables in the public hospitals of kembata Tembaro zone, South Ethiopia, 2019.

Knowledge of health professionals on the IPC measures

Almost all of health professionals, (384, 98.2%) were heard about infection prevention and 389(99.5%) were thought that alcohol based antiseptic is as effective as soap and water if hands are not visibly dirty. While only 160 (40.9%) of respondents were said that safety box should be closed/sealed when three quarters is filled (Table 3).

| Knowledge items (n=391) |

Frequency a |

percentage |

I have heard about infection prevention

principles |

384 |

98.2 |

Gloves cannot provide complete protection

against transmission of infections |

337 |

86.2 |

Washing hands with soap or use of an

alcohol-based antiseptic decreases the

risk of transmission of healthcare acquired

infections |

386 |

98.2 |

Use of an alcohol-based antiseptic for

hand hygiene is as effective as soap and

water if hands are not visibly dirty |

389 |

99.5 |

Gloves should be worn if blood or body

fluid exposure is anticipated |

391 |

100 |

Hand washing is necessary before procedures

are performed |

390 |

99.7 |

Tuberculosis (TB) is carried in airborne particles

that are generated from patients with active

pulmonary tuberculosis |

390 |

99.7 |

There is no need to change gloves between

patients as long as there is no visible

contamination |

335 |

85.7 |

Know how to prepare 0.5% chlorine

solution |

299 |

76.5 |

Safety box should be closed/sealed when

three quarters filled |

160 |

40.9 |

| A Number of health professionals who responded “Yes” for the items |

Table 3 Health professionals’ knowledge regarding infection prevention practice in public hospitals of Kembata Tembaro Zone, South Ethiopia, 2019.

Injuries related to sharp materials and their reasons

One hundred twenty-three (31.5%) of health professionals were encountered needle stick/sharp injury in the last one year. Of these, 70 (60.1%) and 40 (32.5%) were mentioned sudden movement of patient and recapping of used needle as major causes for accidents (Table 4).

| Variables |

Frequency a |

percent |

| Encountered needle stick or sharp injury (n=391) |

123 |

31.5% |

| Major causes of injury (n=123) |

|

|

| Sudden movement of patient |

70 |

60.1 |

| Recapping of used needle |

40 |

32.5 |

| Sharp collection at the site of work |

7 |

5.6 |

| Others |

6 |

1.8 |

a Number of health professional who responded “yes” to item

Table 4 Major causes for sharp injuries among health professionals in public hospitals of Kembata Tembaro zone, SNNP region, Ethiopia, 2019.

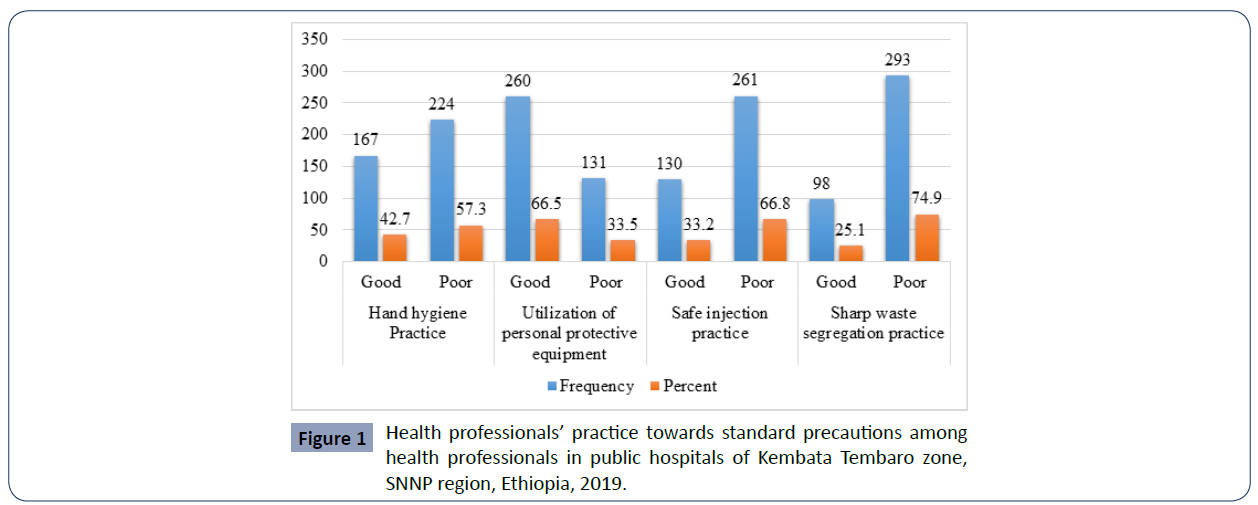

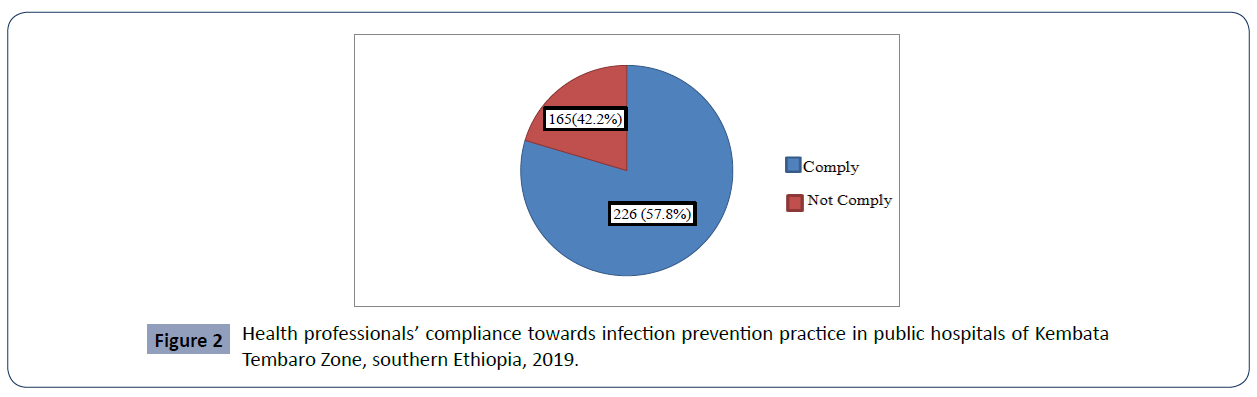

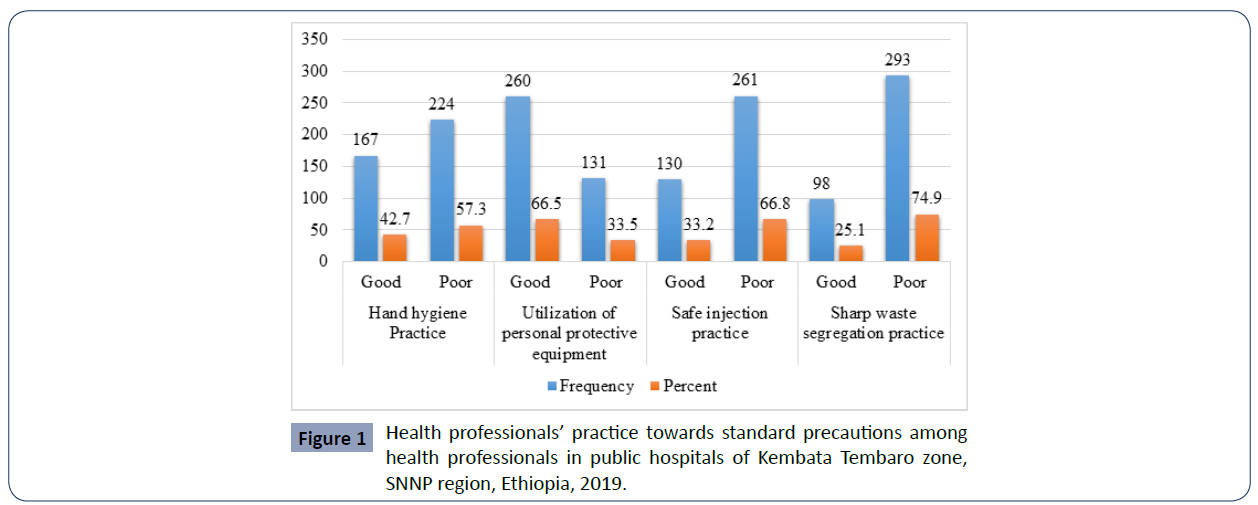

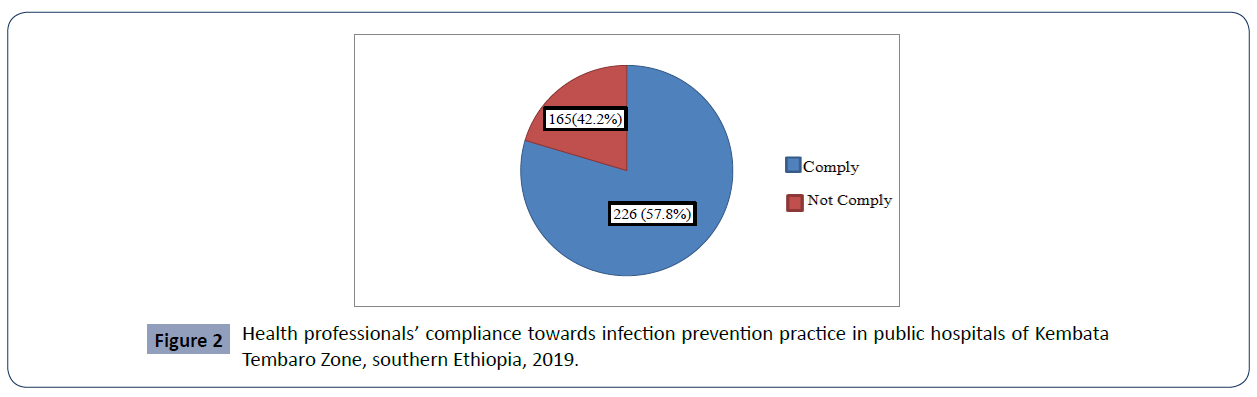

Generally, of 391 study participants, 226(57.8%) were compliant towards infection prevention and practices in the public hospitals of Kembata Tembaro Zone (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1 Health professionals’ practice towards standard precautions among health professionals in public hospitals of Kembata Tembaro zone, SNNP region, Ethiopia, 2019.

Figure 2 Health professionals’ compliance towards infection prevention practice in public hospitals of Kembata Tembaro Zone, southern Ethiopia, 2019.

Factors associated with compliance toward infection prevention practice

Variables which had a significant association in the bivariate analysis (sex, age, marital status, profession, work experience by years, availability of guideline in the working department, educational level, attending training programs on infection prevention and knowledge on infection prevention) at p-value less than 0.25 were entered and analyzed together by multivariable logistic regression. In final model the following variables were identified as independent predictors of compliance to infection prevention practices.

Compliance with infection prevention was about 62% less likely in females than their counterparts (AOR=0.38, 95% CI [0.23- 0.64]). Health professionals who have married were about 2.2 times more likely to comply with infection prevention practice than those who are single (AOR=2.25, 95% CI [1.30-3.88]).

Availability of guidelines in the working departments were 3 times more likely to enhance infection prevention practices of health professionals (AOR=3.08, 95%CI [1.69-5.63]).

Compliance with infection prevention practice was 3 times more likely among health professionals who attended training on infection prevention than health professionals who are not attended the infection prevention training (AOR=3.083, 95% CI [1.69-5.63]).

Compliance with infection prevention practice was about 2.5 times more likely among health professionals who had knowledge of infection prevention practice than their counterparts. (AOR=2.556, 95% CI [1.49-4.4]) (Table 6).

| Variables (n=391) |

Frequency a |

Percent |

| Apply antiseptic hand rub to clean hands |

386 |

98.7 |

| Practice high-level disinfection where sterilization is not applicable |

383 |

98 |

| Use all PEP’s to prevent the risk of acquiring and/or transmitting infection |

381 |

97.4 |

| Practice segregation of liquid and solid healthcare wastes |

22 |

16.6 |

| Change disinfectant chlorine solutions every 24 hours or below |

376 |

96.2 |

| Incinerate or bury used sharp materials |

326 |

83.6 |

| Soak reusable medical instruments in chlorine solution for 10 minutes |

376 |

96.2 |

| wear gloves when I am exposed to body ?uids |

364 |

93.1 |

| Use necessary personal protective equipment if splashes and spills of any body fluids |

314 |

80.3 |

| Usually put sharp disposal boxes at hand reach area |

228 |

58.3 |

a Number of health professional who responded “yes” to items

Table 5 Compliance among health professionals regarding infection prevention practice in public hospitals of Kembata Tembaro, South Ethiopia, April, 2019.

| Variables (n=391) |

Infection Prevention Practice |

COR (95% CI) |

AOR (95% CI) |

P-value |

| Comply |

Not comply |

|

|

|

| Sex |

Male |

151 |

53 |

1 |

1 |

|

| Female |

75 |

112 |

0.38(0.25-0.57) |

0.38(0.23-0.64) |

<0.001* |

| Age |

20-29 |

87 |

103 |

1 |

1 |

|

| >= 30 |

139 |

62 |

2.65(1.75-4.01) |

1.39(0.66-2.94) |

0.391 |

| Marital status |

Single |

56 |

96 |

0.237(0.15-0.37) |

1 |

|

| Ever Married |

170 |

69 |

1 |

2.25(1.3-3.88) |

0.001* |

| Category of health professionals |

Doctor |

53 |

29 |

1 |

1 |

|

| Nurse |

130 |

121 |

0.588(0.35-0.99) |

0.49(0.26-0.91) |

0.025* |

| Others |

43 |

15 |

1.569(0.75-3.29) |

1.17(0.5-2.74) |

0.719 |

| Service year |

Less than or equal to five years |

102 |

69 |

1 |

1 |

|

| |

Greater than five years |

63 |

157 |

0.23(0.18-0.41) |

1.42(0.73-2.78) |

0.301 |

| Educational Status |

Diploma |

40 |

31 |

1 |

1 |

|

| |

First degree |

157 |

124 |

o.98(0.58-1.66) |

0.57(0.28-1.14) |

0.110 |

| |

Second degree |

29 |

10 |

2.247(0.95-5.30) |

1.51(0.54-4.27) |

0.433 |

| Availability of guideline in the working department |

No |

41 |

69 |

0.31(0.2-0.49) |

1 |

|

| Yes |

185 |

96 |

1 |

3.08(1.69-5.63) |

<0.001* |

| Attending training programs on IPP |

No |

41 |

83 |

0.22(0.14-0.35) |

1 |

|

| Yes |

185 |

82 |

1 |

3.08(1.687-5.63) |

<0.001* |

| Knowledge on IPP |

Knowledgeable |

181 |

97 |

1 |

2.56(1.49-4.40) |

0.001* |

| Not knowledgeable |

45 |

68 |

0.36(0.23-0.56) |

1 |

|

*Significant at p-value less 0.05, COR: Crude Odds Ration; AOR: Adjusts Odds Ration

Table 6 Factors associated with compliance towards infection prevention practice among health professionals in public hospitals of kembata Tembaro Zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2019.

Discussion

According to this study, the proportion of health professionals had a good compliance towards infection prevention practices in the public hospitals was found to be 57.8%. This is in line to study from Otona hospital that indicated 60.5% of healthcare workers had good infection prevention practices [22]. This finding was lesser than studies in done among healthcare providers of Dawuro zone [19] and Addis Ababa [21]. However, it was higher than studies conducted in the Dubti hospital (48.35%) [23], Shenen Gibe hospital (38.8%) [24] and Hadiya (15%) [20]. This might be explained by difference on the study participants, study period, type of health facilities and measurement tools. There are also recent government and/or development partners’ interventions done to improve infection prevention measures. In addition, this difference may also attribute to management process in health facilities like establishment of IPC committee, design strategic and operational plan, supportive supervision and other supports done within the health facilities.

We found that less than three-fourth of health professionals were reported that they had a good knowledge about infection prevention and control practices. The result of this study is higher than finding in the referral hospital of Dubti (50.6%) [23]. But it was less than finding in Otona hospital [22] that reported 99.3% of healthcare workers had a good knowledge. Efforts done through management bodies to provide training or orientation and supportive supervision given on these regards and availability of different guidelines and policy documents on the IPC can explain this variation.

Adherence to hand hygiene was poorly low, particularly in developing countries like Ethiopia, which was only 48.7% of health workers obedient on average [25]. Similarly, in this study only 42.7% of health professionals had a good hand hygiene practice. This finding is lower than study done in the general hospital of Zambia [26] and Abet hospital of Addis Ababa [21], which showed that compliance to hand hygiene were 61% and 51.4% among health professionals, respectively. While it is higher than study conducted in the Hospital of Gondar University [27], which was stated that only 16.5% of healthcare providers comply to hand hygiene. This discrepancy may be due to variations on the access to sanitary facilities and necessary supplies for hand washing in the health facilities and utmost behavior of health workers can affect adherence to hand hygiene.

From this self-reported study, the proportion of health professionals who properly utilized personal protective equipment during working time was 57.3%. This finding is inconsistent to study from health facilities of Dawuro zone [19], which reported that 87.2% of health workers utilize PPE. This can be explained by availability of personal protect equipment supplies and behavior of health professionals. One third of study participants were mentioned that they had safe injection practice and by far lower than a study from Dawuro [19]. One-fourth of health professionals were rated their waste management segregation practice as good. This was slightly lower than the study finding from the health facilities of Gondar [28]. This might be because of variation study period and participants and attitude of health workers, and supplies of necessary waste disposal bins are important factors.

The study findings also revealed that over one-third of health professionals were encountered needle stick or sharp injury in the past one year. The current finding is lower than the studies done in Addis Ababa (66.6%) [34] and Amhara region (43%) [35]. This can be due to recent interventions done by government to improve infection prevention practice, better awareness level and utilization of personal protective equipment among health professionals in the present study help them to reduce this injury.

We also found that female health professionals were 62% less likely to practice infection prevention when compared to their counterparts. In opposite to this, study done in Hadiya reported that female health workers 3 times more likely to practice infection prevention than male workers [20]. The inconsistent might be defined by difference on the educational status of study subjects since it is true that male individuals have better educational opportunities than the female in the countries like Ethiopia. Thus, having better opportunity for education will lead to better understanding of infection prevention and that will in turns affect adherence to IPC.

Another factor which was significantly associated with compliance to infection prevention practice is availability of guidelines in the departments. In same manner, having infection prevention guidelines were 2.4 times and 3 times more likely augment adherence to infection prevention practice of health workers in west Arsi districts [32] and Hadiya zone [20], separately. This could be due to the fact that having access to guidelines helps healthcare providers easily reference infection prevention principles and become master of them through reading repeatedly.

Health professionals who attended training on infection prevention had more compliance to IPC compared to their counterparts. Similarly, health workers who attend training 5 times and 12 times more like adhere to infection prevention practices than who were not had training from studies done in Dawuro [19] and Hadiya [20], respectively. This could be because of giving training on the IPC updates the health professionals’ knowledge and may also increase their motivation to comply with practices. It also implies that necessity of training to improve health workers’ adherence to infection prevention measures.

In this study, having knowledge affects health professional’s compliance with IPC measures. Similarly, study done in Addis Ababa showed that health workers who had good knowledge were 1.5 times more likely on infection prevention measures to practice it than their counterparts [21]. It is true that having access to information on the IPC measures will encourage adherence health professionals to reduce their exposure and risk of encountering HAIs.

Interpretation of this study should take in consideration the following limitations. In this study, self-administered questionnaires were used to collect data from respondents but due to social desirability bias we may over or underestimate level of health professionals’ compliance to infection prevention. In addition, this study only explored experience of health providers through questionnaire while it would better to support these findings by observing their actual practices during working time.

Conclusion

The present study revealed that a significant proportion of health professionals had a good compliance to infection prevention practices. Regarding implementation of standard precautions, a high proportion of health professionals were knowledgeable about infection prevention and utilized personal protective equipment properly. However, the overall level of hand hygiene, safe injection and sharp waste segregation practices among health professionals were considered very low. Factors such as sex and marital status of health professionals, availability of guidelines, training status, and knowledge of health professionals were identified as independent predictors of compliance to infection prevention practices. Therefore, Federal Ministry of Health and Regional Health Bureau should work hard to avail fully infection prevention guidelines and address training gaps that will help to increase knowledge level of health professionals to mitigate problems on the compliance with IPC measures. This could support to translate policy guides to action, which will make the public hospitals safer place for health providers, patients and visitors. Health professionals should utilize availed guidelines to implement standard precautions properly and use vaccination services to improve their health status. Zonal Health Departments and Management bodies of health facilities should supply necessary materials to improve infection prevention practices of their respective facilities. We would also like to recommend for scholars to conduct observational studies specifically to understand behavioral factors that may hinder health professional’s adherence to standard precautions and do best to prepare standardized measurement tools of infection prevention practices at country level.

Conflict of Interest

We all the authors declare that this is an original article that is not published or submitted to other journal and there is no financial or other conflict of interest.

Funding of this Research

Not applicable.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our deepest gratitude for zonal health department of Kembata Tembaro Zone and management body of public hospitals for providing baseline information to conduct this study.

We would also extend our heartfelt thanks for health professionals who participated in this study by sharing their experience on the infection prevention and control measures.

We would like to express our grateful thanks to Jimma University for sponsoring data collection of this research.

Author Contributions

Conception and design of study

TM, SOS and MGG.

Methodology

TM, SOS and MGG.

Data analysis and interpretation

TM, SOS and MGG.

Funding acquisition

TM.

Drafting of manuscript

MGG.

Final approval for submission

TM, SOS and MGG.

39212

References

- World Health Organization (2011) Report on the Burden of Endemic Health Care-Associated Infection Worldwide, USA. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Pittet D, Allegranzi B, Storr J, Nejad SB, Dziekan G, et al. (2008) Infection control as a major World Health Organization priority for developing countries. J Hosp Infect 68: 285-292.

- Collins AS (2019) Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. In: Hughes RG (editor). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, USA.

- Pittet D, Donaldson L (2006) Clean Care is Safer Care: a worldwide priority. Lancet 366: 1246-1247.

- World Health Organization (2019) The burden of health care-associated infection worldwide. Geneva, Switzerland.

- World Health Organization (2019) Health care without avoidable infections: The critical role of infection prevention and control. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Federal Ministry of Health (2010) Ethiopian Hospital Reform Implementation Guide, Ethiopia.

- Federal Ministry of Health (2004) Infection Prevention guidelines for Health facilities in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Centre for Disease Control (CDC) Introduction and transmission of 2009 pandemic Influenza A. HINI virus Kenya 58: 1143-1160.

- WHO Regional officer for Eastern Mediterranean (2010) Infection prevention and control in health care: time for collaborative action. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Stein AD, Makarawo TP, Ahmad MFR (2003) A Survey of Doctors’ and Nurses, Knowledge, Attitudes and Compliance with Infection Control Guidelines in Birmingham Teaching Hospitals. J Hosp Infect 54: 68-73.

- Collins AS (2008) Preventing Health Care–Associated Infections. In: Hughes RG (editor). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, USA.

- US department of Labor (2019) Occupational safety and Health Administration. USA.

- Dziekan G, Chisholm D, Johns B, Rovira J, Hutin YJF (2003) The cost-effectiveness of policies for the safe and appropriate use of injection in healthcare settings. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 81: 277-285.

- Prüss-Ustün A, Rapiti E, Hutin Y (2005) Estimation of the global burden of disease attributable to contaminated sharps injuries among health-care workers. Am J Ind Med 48: 482-490.

- World Health Organization (2002) The world health report 2002 – reducing risks, promoting healthy life. Geneva, Switzerland.

- World Health Organization (2019) Health-care waste. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Allegranzi B, Pittet D (2008) Preventing infections acquired during health-care delivery. Lancet 372: 1719-1720.

- Beyamo A, Dodicho T, Facha W (2019) Compliance with standard precaution practices and associated factors among health care workers in Dawuro Zone, South West Ethiopia, cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 19: 381.

- Yohannes T, Kassa G, Laelago T, Guracha E (2019) Health-Care Workers’ Compliance with Infection Prevention Guidelines and Associated Factors in Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia: Hospital Based Cross Sectional Study. Epidemol Int J 3.

- Sahiledengle B, Gebresilassie A, Getahun T, Hiko D (2018) Infection Prevention Practices and Associated Factors among Healthcare Workers in Governmental Healthcare Facilities in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Sci 28: 177-186.

- Hussen SH, Estifanos WM, Melese ES and Moga FE (2017) Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Infection Prevention Measures among Health Care Workers in Wolaitta Sodo Otona Teaching and Referral Hospital. J Nurs Care 6: 416.

- Jemal S, Zeleke M, Tezera S, Hailu S, Abdosh A, et al. (2018) Health Care Workers' Knowledge, Attitude and Practice towards Infection Prevention in Dubti Referral Hospital, Dubti, North East Ethiopia. International Journal of Infectious Diseases and Therapy 3: 66-73.

- Alemu BS, Bezune AD, Joseph J, Gebru AA, Ayene YY, et al. (2015) Knowledge and Practices of Hand Washing and Glove Utiliz ation Among the Health Care Providers of Shenen Gibe Hospital, South West Ethiopia. Science Journal of Public Health 3: 391-397.

- World Health Organization (2010) Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Mukwato KP, Ngoma CM, Maimbolwa M (2008) Compliance with Infection Prevention Guidelines by Health Care Workers at Ronald Ross General Hospital Mufulira District. Medical Journal of Zambia 35.

- Abdella NM, Tefera MA, Eredie AE, Landers TF, Malefia YD, et al. (2014) Hand hygiene compliance and associated factors among health care providers in Gondar University Hospital, Gondar, North West Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 14: 96.

- Azage M, Gebrehiwot H, Molla M (2013) Healthcare waste management practices among healthcare workers in healthcare facilities of Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia. J Health Pollut 7.

- World Health Organization (2014) Achieving Quality Universal Health Coverage through Better Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Services in Health Care Facilities. a Focus on Ethiopia. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Kelemua G, Gebeyaw T (2014) Assessment of Knowledge, AttitudeaAnd Practice of Health Care Workers on Infection Prevention in Health Institution Bahir Dar City Administration. Science Journal of Public Health 2: 384-393

- Mehrdad A, Mary-Louise ML, Marysia M (2006) Knowledge, attitude, and practices related to standard precautions of surgeons and physicians in university-affiliated hospitals of Shiraz, Iran. Int J Infect Dis 11: 213-219.

- Geberemariyam BS, Donka GM, Wordofa B (2018) Assessment of knowledge and practices of healthcare workers towards infection prevention and associated factors in healthcare facilities of West Arsi District, Southeast Ethiopia: a facility-based cross-sectional study. Arch Public Health 76: 69.

- Federal Ministry of Health (2016) Ethiopian Hospital Services Transformation Guidelines. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Feleke EB (2013) Prevalence and Determinant Factors for Sharp Injuries among Addis Ababa Hospitals Health Professionals. Science Journal of Public Health 1: 189-193.

- Abebe AM, Kassaw MW, Shewangashaw NE (2018) Prevalence of needle-stick and sharp object injuries and its associated factors among staff nurses in Dessie referral hospital Amhara region, Ethiopia, 2018. BMC Research Notes 11: 840.