Keywords

Doctors, physicians, attitudes, attempted suicide, parasuicide, self-poisoning.

Introduction

The cases of suicide in Greece have increased dramatically according to National Statistic Office [1]. In particular, during the years 1999-2009, 4042 suicides were recorded in Greece [1]. Though there are not official statistics on attempted suicide in Greece both media as well as health care workers report that suicide attempts have increased considerably over the last five years. These reports are in line with data from Europe and United States [2]. Hospital admission for deliberate self - harm is 17 times more common than death due to suicide [3].

There are number of studies carried out to explore nurses’ attitudes towards attempted suicide, however, in case of doctors there are a few studies in the literature investigating their attitudes towards this group of patients.

Demirkiran and Eskin [4] state that the majority of those who die by suicide contact health care professionals before killing themselves or attempting suicide. In most cases the brunt of the primary care falls on the physicians and junior doctors and the nursing staff [5]. Therefore physicians have been confronted with an ever increasing number of patients whose illnesses are not primarily organic in the traditional sense and whose family and environmental backgrounds are unfamiliar to them [5].

Dermirkiran and Eskin4 developed a conceptual approach, based on a literature review, which states the factors that shape or influence doctors and nurses reactions to patients who have attempted suicide. In particular, sociodemographics characteristics as such age, sex, marital status, educational level, length of work experience may influence these reactions [6]. In addition, people’s own suicidal tendencies may affect their responses to suicidal people. Dermirkiran and Eskin4 stressed that studies involving health workers’ attitudes towards suicidal patients did not address the effect of their own suicidal tendencies on such attitudes. In terms of social desirability individuals may want to present themselves in a socially desirable manner when dealing with a value–laden issue like suicide [4]. Moreover, health care reactions to patients who have attempted suicide might be influenced by their attitudes towards suicide itself.4 Furthermore, beliefs held by health professionals that people who attempt suicide to manipulate others may result in negative reactions towards such people [7]. Additionally, emotions evoked by a suicidal patient is another factor that may influence doctors reactions to patients who have attempted suicide [8]. Dermirkiran and Eskin’s4 study found that doctors who believed that people should communicate their suicidal problems and felt sympathy for a patient who has attempted suicide predicted therapeutic reactions in positive way, while feeling fear/anxiety for a suicidal patient predicted non therapeutic reactions by the doctors. In addition, doctors who believed that suicide will be punished after death reported negative attitudes towards attempted suicide [4].

Goldney and Bottrill [9] carried out a survey of attitudes of various professionals including doctors towards attempted suicide. It was found a considerable degree of unsympathetic responses particularly from hospital-based medical staff, mainly doctors who have initial contact with these patients. The authors emphasised that the results give grounds for concern, that further suicidal behaviours may be precipitated in such patients if they perceive rejection by therapists. Contact with attempted suicide evokes negative feelings in health personnel. Goldney and Bottrill [9] state that the possibility that such feelings may be detrimental to these patients and may contribute to subsequent suicidal behaviour has also been reported.

Platt and Salter [10] found that compared to physicians, psychiatrists were significantly more likely to agree that parasuicides are rewarding and challenging to care for patients they can “really help”. Their study confirms the results of other studies in which psychiatrists present more positive attitudes compared to physicians. However, Platt and Salter [10] referring to Hawton et al [11] argue that this tendency may reflect the different roles these professional groups have in the care of attempted suicide patients.

In another study negative attitudes towards self-poisoning were demonstrated by junior doctors and housemen, whereas consultants and senior registrars reported feeling neutral to self-poisoning patients [12]. In Ramon et al’s study [13] doctors distinguished between “suicidal” motives, of which they were relatively accepting and “manipulative” motives which they accepted less.

Bailey [14] asserts that critical care doctors attitudes to parasuicide patients are complicated and tend to be negative. 44% of respondents agreed or agreed strongly that doctors did not appear to display much patience towards parasuicide patients. The emotions involved include anxiety, guilt, and anger about “waste” is often the predominant emotion. The survey showed that doctors’ attitudes to parasuicide patients were generally negative and that respondents did not enjoy caring for that group of patients. An interesting finding was that 61% of the doctors stated that they would benefit from education about suicide.

Osborne [15] states a patient who has attempted suicide creates a unique situation in ICU because energy is directed to resuscitating and maintaining the life of someone who has demonstrated that he or she wishes to die.

Patel5 carried out a study to investigate doctors’ attitudes to self-poisoning. He found that consultant staff didn’t express unfavourable attitudes compared to junior medical staff who more frequently presented unfavourable attitudes to self-poisoning patients. However, he also found that half of the consultants think that the general attitude of medical staff to the self-poisoned patient is unfavourable. The negative attitudes of junior medical staff might be explained by the fact that they have a greater degree of contact with self-poisoning patients.5 Doctors showed a preference for treating physically ill; unfavourable attitudes were never expressed about the group of patients with cardiac infraction.

The unfavourable attitudes to self-poisoned patients must be considered in relation to preventive measures, and especially in the cases of the frequent “repeaters” [5]. The author points out that doctors’ general opinion was that nearly all cases of self-poisoning result from social rather than psychiatric problems. The majority of the doctors felt that these patients were unsatisfactory to treat or nurse and did not benefit from their stay in hospital [5]. They also felt that these patients should be admitted in specialized units, in order to lighten the burden on the general medical wards.5 Suokas and Lonnqvist [16] compared the attitudes of nurses and doctors in various departments and found that the most negative attitudes were held by nursing and medical staff working in emergency departments and the most positive by intensive care unit staff. People who made repeated suicide attempts and frequent visits to the emergency room were considered to cause stress to carer’s and dissatisfaction with their work.

The negative attitudes towards attempted suicide were confirmed by studies carried out to explore patients’ view on the care they received during their admission in a hospital. It has been reported that staff was not well trained to treat them and patients felt that the health care personnel held negative attitudes towards them [17]. Some patients reported that they were treated differently from other patients in accident and emergency departments and related this to the fact that they had harmed themselves [18]. In addition, many service users complained that A & E staff were unconcerned with their mental health and concentrated solely on their physical problems [19]. Moreover, attempted suicide patients reported long waiting times with a lack of information about their physical status which made some of them anxious and frightened [20]. Furthermore, attempted suicide patients had negative perceptions of interactions with staff which centred upon perceived inappropriate behaviours and lack of empathy. In addition, attempted suicide patients felt threatened and humiliated by staff in relation to their physical management [21]. Some patients felt staff threatened to withhold treatments (e.g. anaesthetic during suturing) because their injuries were self-inflicted unless they promised not to self-harm again [22].

Some patients did however report positive experiences of physical management which were associated with staff’s concern about patients’ psychological status during physical treatment [22]. Though psychological assessment is part of recommended care for attempted suicide presenting to hospitals, [21,23] many patients are not assessed [24,25]. When staff provides attempted suicide patients the opportunity to talk about problems they reported more positive experiences [22]. However, the majority of patients perceived the assessment to be superficial and rushed [26]. Taylor et al [17] in a systematic review of attitudes towards clinical services of individuals who self-harm showed that in spite of differences in country and health care systems, many participants’ reactions to and perceptions of their management were negative. Therefore, doctors may play an active part in the treatment and prevention of patients going through the suicidal process [4]. In addition, therapeutic reactions from doctors may present an opportunity for interrupting an ongoing suicidal process [6]. Therapeutic reactions by doctors may signal to the patient that he is valued and being taken seriously.4 In contrast, countertherapeutic reactions, may be taken by the suicidal patient as further proof of his worthlessness and hence may further exacerbate an ongoing suicidal process [27].

However, frequent suicide attempts increase the likelihood of suicidal people dying in subsequent attempts. Failure to recognize and respond to the needs of such people may have contributed to subsequent death by suicide [28]. Therefore, doctors’ awareness of their attitudes towards attempted suicide remain of paramount importance if the rate of suicide attempts is to be decreased through providing those patients with dignified care and proper guidance.

The main aim of the study was to explore doctors’ attitudes towards attempted suicide patients.

Methodology

Objectives

1st To examine the attitudes of doctors to attempted suicide patients.

2nd To explore respondents’ feelings in response to the hospitalization of attempted suicide patients.

3rd To identify if independent variables such as demographic variables, professional characteristics, would have an influence on medical staff attitudes towards attempted suicide patients.

4th To identify if other variables such as respondents’ personal acquaintance with a person who committed suicide, would have an impact on medical staff’s attitudes.

5th To identify possibly different attitudes of doctors’, working in several specialties towards attempted suicide patients.

6th To identify predictive variables which form doctors’ positive attitudes towards attempted suicide.

Research design

In order to achieve the aim and the objectives of the study a cross-sectional research design was utilised. The variables investigated in the study were distinguished as independent and dependent variables.

Sample and research site

Data were collected from a convenience sample of doctors working in medical, surgical, orthopaedic as well intensive care units (ICU) of four general hospitals in Greece. Participation in the study was voluntary.

Ethical issues

The directors of the medical staff of the four hospitals approved this study. Doctors who were interested in participating were reassured of anonymity of responses as well as their right to withdraw at any time. Implied consent to participate was assumed by completion and return of the questionnaire.

Instrument

Data were collected using the likert type questionnaire “Attitudes Towards Attempted Suicide-Questionnaire” (ATAS-Q) [29] developed in another study to assess doctors’ and nurses’ attitudes towards attempted suicide. The ATAS-Q comprises 80 items measuring health care professionals’ attitudes towards attempted suicide. The questionnaire consists of 8 factors (F1 “positiveness”, F2 “acceptability”, F3 “religiosity”, F4 “professional role and care”, F5 “manipulation”, F6 “personality traits”, F7 “mental illness”, F8 “discrimination”) and each factor reflects different attitudinal aspects. The questionnaire was likert type (1=strongly disagree, 2= disagree, 3= undecided, 4=agree and with 5=strongly agree). Negative and positive statements were included in order to avoid participants’ tendency to agree with positively worded items [30]. The possible score ranges from 80 (which reflects the most negative attitudes) to 400 (which reflects the most positive attitudes towards attempted suicide). Two independent researchers were asked to assess the validity of the questionnaire and reported that it has high content and face validity. The scale presented high internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha a=0.97 [29]. In addition, after the completion of the study when internal consistency was assessed Cronbach’s alpha was a=0.88 which is satisfactory. Moreover, the questionnaire also recorded demographic variables such as doctors’ professional and personal characteristics (length of professional experience, department of work, respondents’ level of religiosity, any personal suicidal thought and respondents’ experience of having known someone who had committed suicide).

Data analysis

Data collected were analysed using SPSS version 17. Descriptive and inferential statistics were utilized to analyze the data. With respect to the scale measuring medical staff’s attitudes towards attempted suicide the mean and standard deviation for each of the 8 factors of the scale were established as well as the total score of the scale. In addition, one way Analysis of Variance was used in order to identify statistical significant differences between the independent variables in relation to the dependent variable “attitudes towards attempted suicide” which measured with ATAS-Q. Multiple regression analysis was used to identify predictors of doctors’ attitudes towards attempted suicide patients. The acceptable level of statistical significance was the P< 0.05.

Results

Sociodemographic

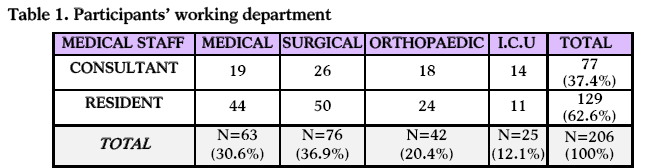

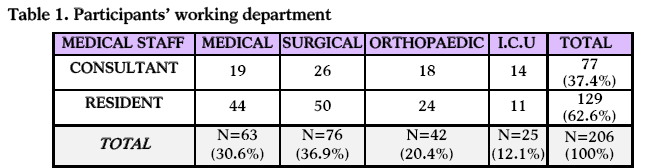

Two hundred and six (N=206) medical staff participated in the present study. Overall response rate was 63%. Of the respondents 37.4% (n=77) were consultants and 62.6 (n=129) were residents (Table 1). Of the medical staff 30.6% were working in medical departments, 36.9% in surgical, 20.4% in orthopaedic and 12.1% in ICU. Respondents’ mean age was 40.2 years (SD=6.1).

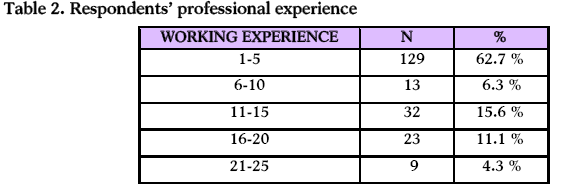

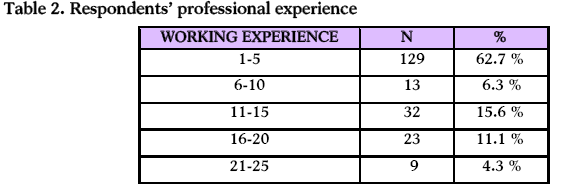

The vast majority of the participants (62.7%) had 1-5 years working experience, 6.3% 6-10 years, 15.6% 11-15 years, 11.1% 16-20 years and 4.3% 21-25 years professional experience (Table 2).

Of the participants 31.5% held a PhD in medicine and a very small proportion (4.3%) had completed a master degree.

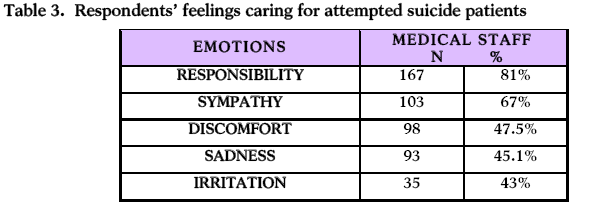

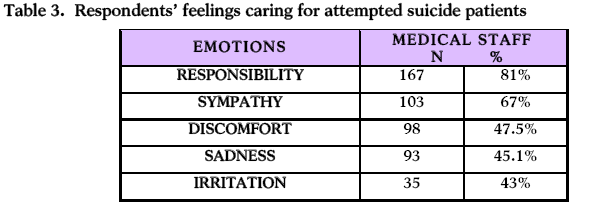

Table 3 illustrates participants’ feelings when treating an attempted suicide patient. Respondents described that they experienced a variety of feelings in response to the hospitalization of attempted suicide patients. Such feelings were responsibility (81%), sympathy (67%), discomfort (47.5%) and sadness.

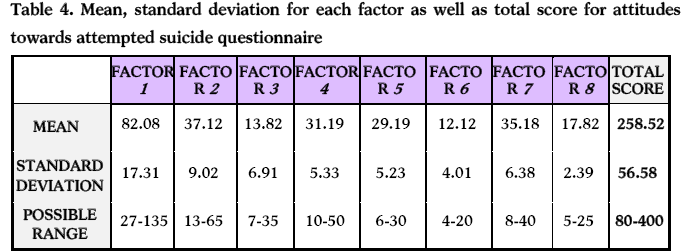

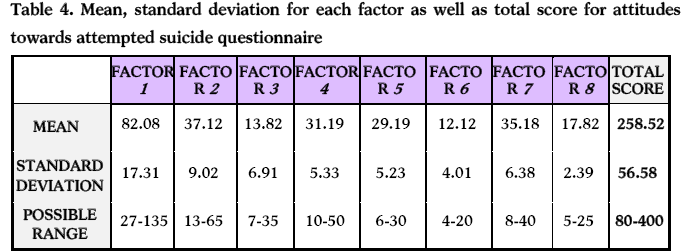

One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that overall respondents held relatively unfavourable attitudes towards attempted suicide (M=258.52; SD=56.58) as illustrated in table 4. However, the mean score of the 1st factor “positiveness” reflects respondents’ positive attitudes towards attempted suicide. The mean score of factor 2 “acceptability” might reflect participants’ neutrality towards people who attempt to suicide. The mean score of the 3rd factor “religiosity” reflects participants’ relatively less affect in forming attitudes towards attempted suicide people. Factor 4th “professional role and care” reflects participants views of the care that attempted suicide patients receive as well as the professional role and work environment of medical staff. The mean score shows that people who attempt to suicide are treated in a relatively favourable environment. With respect to factor 5 “manipulation” the mean score shows that respondents consider attempted suicide people as relatively manipulative. The mean score of the 6th factor “personality traits” shows that respondents hold relatively favourable views on attempted suicide people’s personality traits. The relatively low mean score of factor 7 “mental illness” reflects participants’ views that the act of attempting suicide is related to mental illness. The mean score of the 8th factor “discrimination” reflects positive disposition to attempted suicide people with doctors demonstrating very low levels of discrimination to those people (Table 4).

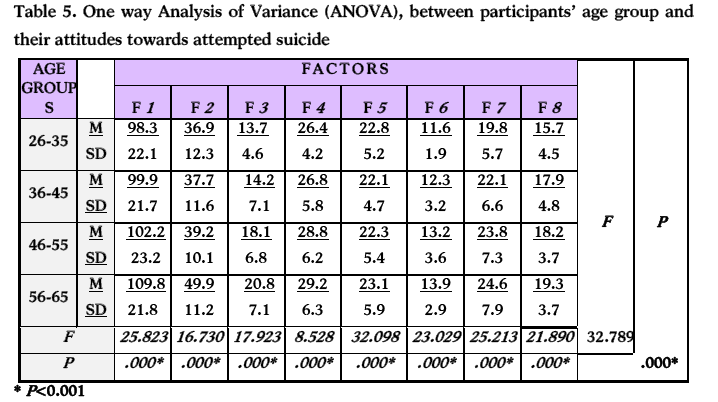

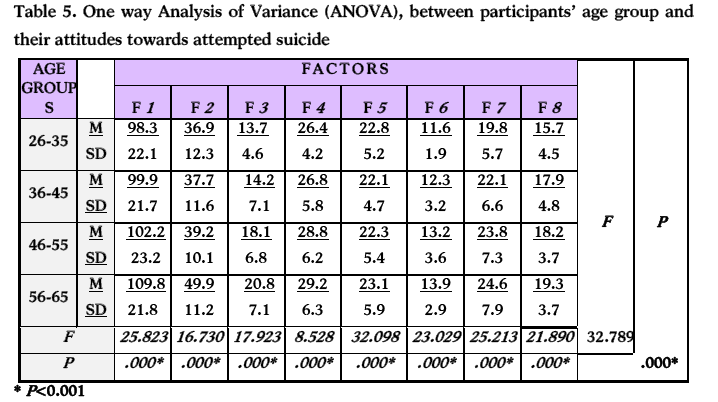

Table 5 illustrates that the most favourable attitudes towards attempted suicide were held by those in the age group 56-65 years old. In addition, it shows that the younger medical staff held less positive attitudes and medical staff’s attitudes became more favourable as their age increased.

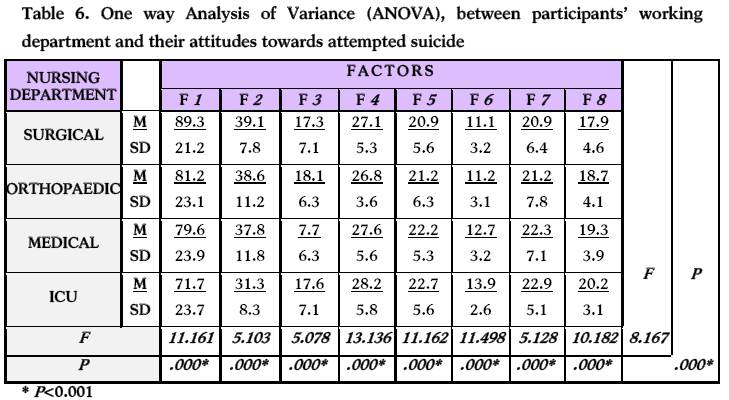

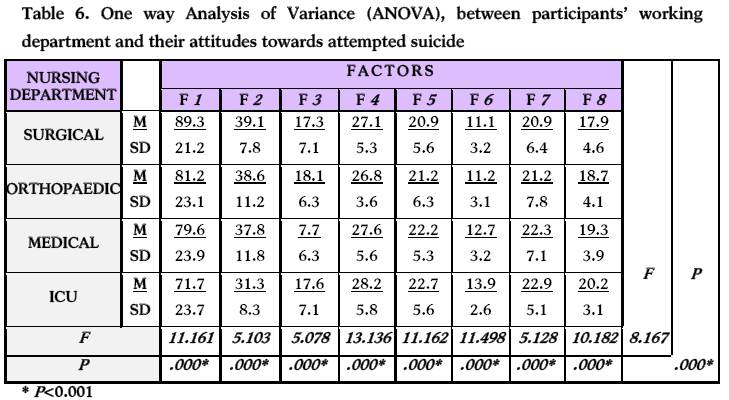

In regard to department and doctors’ attitudes towards attempted suicide the results show that the most favourable attitudes were held by doctors working in surgical wards and in sequence in orthopaedic, medical, and the most unfavourable attitudes were held in ICU (Table 6). In addition, table 6 shows the doctors’ attitudes from different departments towards the other factors of the ATAS-Q [27].

One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) between attitude and respondents who reported that they had contemplated suicide once in their life, revealed that these doctors’ reported that they held statistically significant more favourable attitudes compared to those reported that they had never contemplated suicide (F=103.167; P=0.001). In addition, respondents’ who had had a relationship with a person who had committed suicide reported statistically significant more positive attitudes towards patients who had attempted suicide (F=102.183; P=0.001) .

Multiple regression analysis found that predictive factors at statistically significant level (R2 0.387; P=001) that influenced doctors’ favourable attitudes towards attempted suicide were age, and contemplation of suicide.

Discussion

Overall respondents displayed relatively unfavourable attitudes towards attempted suicide which is in congruence with other studies [5,14,16]. Even psychiatric residents expressed more favourable attitudes towards low suicide risk and limited overall psychopathology [31]. Positive attitudes are important because people who had attempted suicide reported negative perceptions of interactions with staff which centred upon perceived inappropriate behaviours and lack of empathy and perceived threats and humiliation related to their physical management [21]. In contrast, some patients reported positive experiences of physical management and were associated with staff’s concern about patients’ psychological status during physical treatment [22]. Samuelsson et al [6] state that therapeutic reactions from doctors may present the opportunity for interrupting an ongoing suicidal process. In particular, therapeutic reactions by doctors may signal to the patient that it is valued and taken seriously [4].

In regard to the ATAS-Q’s factor “positiveness” doctors scored relatively high, this might reflect their professional attitudes to treat all patients equally and not their attitudes towards attempted suicide patients. In addition, this discrepancy supports the fact that attitude towards attempted suicide is a complex phenomenon and there is not just positive or negative. There are other mediating variables that influence medical staff’s attitudes towards attempted suicide patients.

With respect to the factor “acceptability” respondents’ displayed relatively neutral attitudes towards attempted suicide.

In regard to participants’ influence of “religiosity” in forming attitudes towards attempted suicide the mean score suggests that it doesn’t affect their attitudes. Similarly, participants’ professional role and working environment don’t play an influential role in forming a strong favourable or unfavourable attitude. Surprisingly in the factor “manipulation’ doctors showed that they believe that attempted suicide people are manipulative.

In respect to attempted suicide and personality traits, participants displayed neutral attitudes towards this group of patients. In contrast, participants considered attempted suicide as people with mental health problems. The relationship between attempt suicide and mental illness reflects Greek doctors’ social norms rather than their professional attitudes towards those patients. Doctors’ professional behaviour is also reflected by the fact that in factor “discrimination” they showed that they don’t discriminate against attempted suicide patients.

It is noteworthy that participants expressed a variety of feelings equally positive and negative towards attempted suicide which shows ambivalent emotions towards these people. This result can justify the contradictory findings, from one part doctors overall reported relatively unfavourable attitudes towards attempted suicide whereas, in the factor “positiveness” they displayed favourable attitudes towards attempted suicide. It has to be stressed that the majority of previous studies have avoided addressing emotional reactions of care-givers to attempted suicide or suicidal patients [4]. However, a few studies reported that health personnel experienced ambivalence, frustration, and distress with the specific group of self-harming patients [32-34].

Respondents age showed statistical significant (p=0.001) influence on attitudes. In particular, respondents who were younger and had less working experience held more unfavourable attitudes compared to older and more experienced doctors. It seems that younger doctors (residents) carry the brunt of direct involvement with an attempted suicide patient and potentially are more stressed due to the responsibility they held for patients’ physical protection. The above finding was congruent with a study exploring the therapeutic and non therapeutic reactions in a group of nurses and doctors in Turkey to patients who have attempted suicide.4 Similarly, O’Brien [12] found that junior doctors held more unfavourable attitudes towards attempted suicide, whereas senior registrars and consultants reported feelings neutral to self-poisoning patients.

Participants working in surgical departments showed the most favourable attitudes towards attempted suicide apparently because they don’t treat quite often that group of patients; therefore they have less possibility to face difficulties with them. Similarly, medical staff working in orthopaedic departments displayed more favourable attitudes compared to those working in Medicine and ICU. The fact that orthopaedic doctors also held positive attitudes may relate to the fact that attempters often choose falls as a mean to commit suicide and doctors may feel sympathy towards those patients and the very difficult situation that they experience after a fall. Medical units often treat overdose patients and the medical staff might feel high level of responsibility for patients’ care. Doctors working in ICU’s presented the most unfavourable attitudes towards attempted suicide. It is self-evident that doctors working in ICU’s face a pressure to manage critically ill patients. The fact that attempted suicide is a self-destructive behaviour and it is not caused by either accident or independent physical cause might evoke negative feelings in doctors towards those patients. Moreover, in intensive care units the number of beds are limited world while and medical staff may find themselves expected to transfer critically ill patients who did not deliberately cause their critical condition. In contrast to the finding of the present study Suokas and Lonnqvist16 found that the most positive attitudes towards attempted suicide were held by intensive care units staff.

Other factors were found to influence doctors’ attitudes; especially, doctors who had previously contemplated suicide, or had had a relationship with a person who had committed suicide reported more favourable attitudes towards patients who had attempted suicide. This finding is in line with a study carried out in nurses and doctors in Turkey [4]. In contrast to the findings of the present study attitudes to parasuicide patients were not influenced by any of the variables of having or not having personal experience of suicide [4].

It is evident from the literature that attitudes can affect care decisions and negative attitudes, of which medical staff is unaware, could jeopardize patients’ best care and safety. Thus, it is vital to improve the educational preparation of medical staff for improving awareness, of the impact of their attitudes towards attempted suicide patients.

Limitation of the study

This study illustrated the spectrum of attitudes that medical staff holds in a variety of settings. The cross-sectional research design used restricts the generalisability of the findings. However, the value of the findings is that the results illustrate that attitudes towards attempted suicide are complex and there is more than one factor which formulates a favourable or unfavourable attitudes towards them.

Conclusions

The study revealed that doctors held relatively unfavourable attitudes towards attempted suicide. These attitudes are related to the feelings that doctors hold to these patients, the social norms that influence these attitudes as well as the context that doctors work in their working clinical environment. In contrast, older doctors with more professional working experience, the department they work in as well as the experience of having contemplated suicide or having had a relationship with a person who committed suicide, produced more favourable attitudes towards attempted suicide. Therefore, it is a priority for medical staff to transform their attitudes through training and reflection in order to be more favourable and therapeutic towards attempted suicide patients, helping them to eliminate the potential of a future attempt to suicide. In addition, medical students must be trained to treat attempted suicide as well as to increase their understanding of difficulties might face most of attempted suicide patients, so as to become more empathetic to those group of patients.

3150

References

- McCann TV, Clark E, McConnachie S, Harvey I. Deliberate self-harm; emergency department nurses’ attitudes. Triage and care intentions. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2007; 16(9):1704-1711.

- Calof DL. Chronic self–injury and self-mutilation in Adult Survivors of Incest and childhood sexual Abuse: Aetiology, Assessment and Intervention. Family Psychotherapy Practice of Seatle, Washington, 1994.

- Demirkiran F, Eskin M. Therapeutic and nontherapeutic reactions in a group of nurses and doctors in Turkey to patients who have attempted suicide. Social Behavior and Personality 2006; 34(8):981-905.

- Patel A.R. Attitudes towards self-poisoning. British Medical Journal 1975; (2):426-430.

- Samuelsson M, Asberg M, Gustavsson JB. Attitudes of psychiatric nursing personnel towards patients who have attempted suicide. ActaPsychiatricaScandinavica 1997; 95:222-230.

- Eskin M. The effects of religious versus secular education on suicide ideation and suicidal attitudes in adolescent in Turkey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 2004; 39(7):536-542.

- Wolk-Wasserman D. The intensive care unit and the suicide attempt patient. ActaPsychiatricaScandinavica 1985; 71:581-595.

- Goldney R, Bottrill A. Attitudes to patients who attempt suicide. Medical journal of Australia 1980; 2:717-720.

- Platt S, Salter D. A comparative investigation of health workers’ attitudes towards parasuicide. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 1987; 22(4):201-208.

- Hawton K, Marsack P, Fagg J. The attitudes of psychiatrists to deliberate self-poisoning: comparison with physicians and nurses. British Journal of medical psychology 1981; 54:341-348.

- O’Brien SEM, Stoll KA. Attitudes of medical and nursing staff towards Self-poisoning patients in a London hospital. International Journal of Nursing Studies 1977; 14:29-35.

- Ramon S, Bancroft HJ, Skrimshire AM. Attitudes towards self-poisoning among physicians and nurses in a general hospital. British Journal of Psychiatry 1975; 127:257-264.

- Bailey S. Critical care nurses’ and doctors’ attitudes to parasuicide patients. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 1994; 11(2):11-17.

- Osborne MJ. Suicide and the response of the critical care nurse. Holistic Nurse Practitioner 1989; 4(1):18-23.

- Soukas J, Lonnqvist J. Work stress has negative effects on the attitudes of emergency personnel towards patients who attempt suicide. ActaPsychiatricaScandinavica 1989; 79(5):474-480.

- Taylor TL, Hawton K, Fortune S, Kapur N. Attitudes towards clinical services among people who self-harm: systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2009; 194(2): 104-110.

- Harris L. Self-harm: cutting the bad out of me. Qualitative health Research 2000; 10:164-173

- Brophy M. Truth hurts: report of the national inquiry into self-harm among young people. Mental Health Foundation, 2006.

- Cerel J, Currier GW, Cooper J. Consumer and family experiences in the emergency department following a suicide attempt. Journal of Psychosocial Research 2006; 12:341-347.

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Clinical Guideline16. Self-Harm: the Short Term Physical and Psychological Management and Secondary Prevention of Self-Harm in Primary and Secondary Care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2004.

- Palmer L, Strevens P, Blackwell H. Better Services for people who Self-Harm. Data summary – Wave 1 Baseline data. Royal College of Psychiatrist, 2006.

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. The General Hospital Management of Adult Self-Harm: A Consensus Statement on Standards for Service Provision. Royal College of Psychiatrist, 1994.

- Bennewith O, Gunnel D, Peters T, Hawton K, House A. Variations in the hospital management of self-harm in adults in England: observation study. BMJ 2004; 328:1108-109.

- Kapur N, House A, Creed F, Feldman E, Guthrie E. Management of Deliberate self-poisoning in adults in four teaching hospitals: descriptive study. BMJ 1998; 316:831-832.

- Hengeveld MW, Kerkhof AJFM, Van der Wal J. Evaluation of psychiatric consultations with suicide attempters. ActaPsychiatricaScandinavica 1988; 77:283-289.

- Eskin M. A cross-cultural investigation of the suicidal intent in Swedish and Turkish adolescents. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 2003; 44:1-6.

- Foold RA, Seager CP. A retrospective examination of psychiatric case records of patients who subsequently committed suicide. British Journal of Psychiatry 1968; (114):443-450.

- OuzouniChr, Nakakis K. Attitudes towards attempted suicide: the development of a measurement tool. Health Science Journal 2009; 3 (4):222-231.

- Topt M. Response sets in questionnaire research. Nursing Research 1986; 35(2):119-120.

- Dressler DM, Prusoff B, March H, Shapiro D. Clinician attitudes toward the suicide attempter. The journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 1975; 160(2):146-155.

- Alston M, Robinson B. Nurses attitudes towards suicide. Omega 1992; 25(3):205-215.

- Palmer S. Parasuicide: a cause for concern. Nursing Standard 1993; 7(19):37-9.

- Hemmings A. Attitudes to deliberate self-harm among staff in an accident and emergency team. Mental Health Care 1999; 2(9):300-302.