Keywords

Fatherhood; First-time fathers; Transition; Qualitative study

Introduction

Background

Becoming a parent involves a major transition in life. The change leads to new roles and brings joy, expectations, challenges and obligations for the individual parent and for the couple as a whole. The sense of coping and the way that this transition is experienced have implications for the bond with the child, the child’s upbringing and the development of the family [1-4]. Fatherhood has changed over time, with greater demands and expectations of fathers’ participation than before. Society has become more receptive to the increased presence of both parents. Men who start a family today are expected to create their own role as a father and to find a balance between their job, childcare, housework and hobbies, on an equal footing with women. Norway is in a unique position regarding shared parental leave, compared with other countries [5,6]. The focus of well child clinics has shifted from the mother and child to the family. The gender perspective and men’s needs are supposed to be key elements in the design of antenatal care and well child clinic services [7]. However, recent guidelines vary in the degree to which they emphasize the father’s role as an independent function and the father is often referred to mainly as a support person for the mother [7,8].

New parents find themselves in a vulnerable phase [8]. They alternate between joy and worry. Roles change, individually and in relation to each other [4,9]. The way parenthood is handled depends on how the realities of this role are experienced from the perspective of predictability and perceived consistency. Antonovsky terms this a sense of coherence (SOC). He describes three component factors – comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness – all of which are essential to a sense of coping, health and well-being in the new role [10]. A lot of research has focused on the mother’s role. Despite growing interest in research on the father’s role, few Norwegian studies address the fatherhood experience. Research has shown that men’s health is affected by the life transition that becoming a father entails. Fathers undergo biological and psychological changes [11] and studies show increased incidence of depression in new fathers [6,12,13] compared with the male population in general. More knowledge about the father’s role is important to enable public health nurses to understand fathers better and to be more aware of their challenges and circumstances. Encouragement of a more active and participating role for the father is consistent with national and political goals in Norway [7,14] and is important to make it possible to provide good support, guidance and follow-up to the new family. The objective of this study was to explore how men experience becoming a father for the first time. We wanted to explore how first-time fathers experienced the transition to fatherhood and how they described their role during the pregnancy, childbirth and the child’s first three months of life.

Methods

The study has a qualitative design, with individual interviews as the data collection method. This form seeks to understand more than explain individual experiences [15,16]. A semi structured interview guide was developed. The interview guide consisted of open main questions based on the research questions, as well as more detailed follow-up questions. The follow-up questions allowed the interviewer to explore the material in greater depth [15,16].

Sample

The informants were recruited by public health nurses at four well child clinics in a medium-sized municipality in southeastern Norway that included both urban and rural areas. The public health nurses presented the study during the home visit or the six-week consultation. All fathers in the target group were invited to participate. The inclusion criteria were: firsttime father, adequate ability to speak and understand Norwegian, and child’s age about three months at the time of the interview. The sample size was assessed on the basis that saturation can be achieved when there seems to be no new information [15]. In this study, we interviewed nine fathers.

Data collection

The first author conducted the interviews. The informants spoke freely in answer to the main questions, and the followup questions were infrequently used. The interviews took place from May to December 2016, lasted from 45 to 75 minutes and were tape-recorded. The interviews took place in neutral, undisturbed meeting rooms: eight at well child clinics, except for one that took place at the informant’s workplace. Transcription took place continuously. The audio recordings were reviewed and compared with the transcribed text, to ensure trustworthiness [15].

Analysis

Soundtracks and transcriptions were available to both authors. The analysis was inspired by Graneheim and Lundman qualitative content analysis [17]. The method of analysis includes the manifest and latent content of the data material and has an inductive approach. This approach is suitable for analysis of qualitative data where the aim is to describe the informants’ experiences [15,17]. All the interviews were read and meaning units were identified. The units were then condensed and coded. The codes were sorted into sub-themes and then themes. The analytic process is shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Example of the qualitative content analysis.

| Meaning units |

| I’m aware that I am an apprentice; I don’t feel confident in the role, in a way. |

I wouldn’t call it depression or that sort of thing, but it becomes… yes… you can get irritable, that’s true. |

I don’t have any contact with other fathers who are in exactly the same situation… |

When you get home from work, then Mum has changed enough diapers for that day, so then it’s… then there’s an expectation that Dad will take over…. |

| Condensed units |

| Not confident in the role |

Can become irritable |

Little contact with other fathers |

When the father comes home from work, he is expected to take over the responsibility for the child from the mother |

| Codes |

| Lack of confidence |

Irritability |

Small network |

Sharing of responsibility |

| Sub-themes |

| Low degree of coping |

Negative health |

Relationship challenges |

Everyday demands |

| Theme |

| Barriers to the fatherhood role |

Ethical considerations

The informants received oral and written information about the study and its purpose. All participation was voluntary. The informants provided written consent, and had the opportunity to withdraw at any time during the study. The data were anonymized and treated confidentially. The authors did not participate in recruitment. The participants were offered follow-up dialogues with a public health nurse if needed. The study was approved by the Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD) (project number 47652) and was conducted in accordance with the guidelines for research ethics [18].

Results

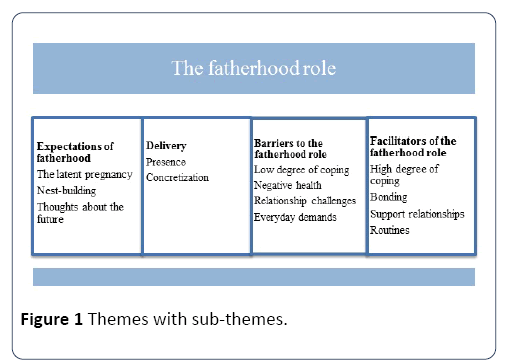

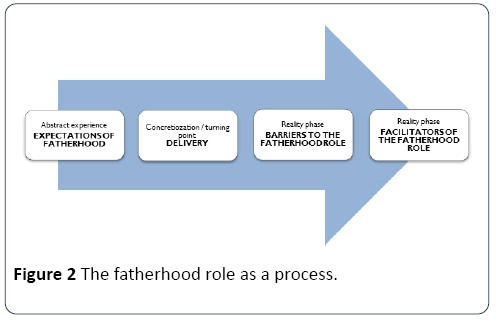

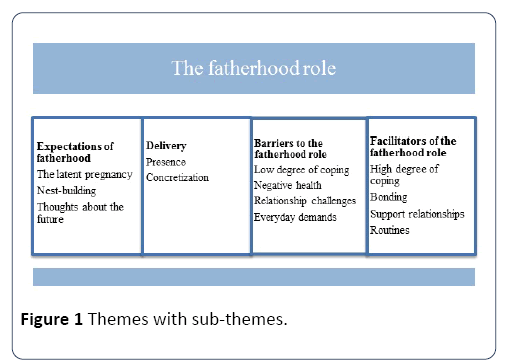

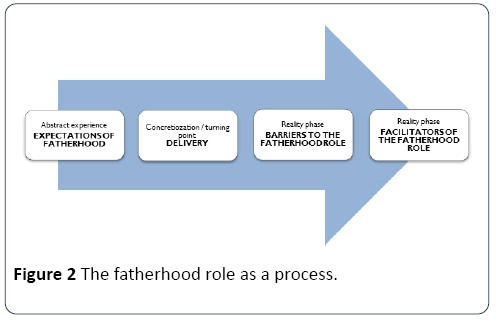

The men’s ages were from 25 to 45 years. They were all Norwegian, seven were cohabitants, and two were married (Table 2). The analysis resulted in four themes describing the fathers’ experience of their role as fathers (Figure 1). The fatherhood role progresses through all the themes and can be seen as a process (Figure 2). The results are presented below with quotations from the fathers.

Table 2 Participants in the study.

| Age |

25-45 years |

| Average age |

30.7 years |

| Nationality |

All Norwegian |

| Marital status |

| Cohabitant |

7 |

| Married |

2 |

| Housing |

| Owned housing |

8 |

| Rented housing |

1 |

| Detached/semi-detached house |

6 |

| Apartment |

0 |

| Dwelling type not specified |

3 |

| Education |

| Upper secondary school |

3 |

| University college/University |

6 |

| Length of relationship with partner before birth of the first child |

2-10 years |

| Average length of relationship |

5 years |

| Child’s age at the time of the interview |

12-18 weeks |

| Average age |

15 weeks |

| Own childhood |

| Grew up with both parents |

8 |

| Grew up with one parent |

1 |

| Only child |

1 |

| Siblings |

8 |

| Number of siblings |

01-Mar |

| Participation in encounter with health services |

| Antenatal appointment with midwife |

5 |

| Childbirth |

9 |

| Home visit by public health nurse |

7 |

| Six-week consultation at the well child clinic |

5 |

| Three-month consultation at the well child clinic |

5 |

Figure 1: Themes with sub-themes.

Figure 2: The fatherhood role as a process.

Expectations of fatherhood

The father’s expectations started to take shape during the pregnancy. The fathers described the pregnancy as an abstract phase, marked by excitement and feelings of unreality. Several felt unsure about their own role and what they should be preparing for. The baby seemed abstract and unreal. The feelings of uncertainty emerged regardless of whether the pregnancy was planned or not.

I was overlooked during the pregnancy and did not feel so very much. I had nothing tangible to relate to. She had something in her belly, she could feel it. I didn’t have that.

Usually, the pregnancy was defined in terms of the mother’s health. If the mother was in good health, the pregnancy was experienced as proceeding smoothly without problems. Correspondingly, if the mother had health issues, either physical or mental, a negative focus resulted. The father’s role became subordinate to the mother’s, and the mother’s health became more definable than the child itself. Fathers experienced high expectations that they would be a key resource for the pregnant woman - from themselves, their partner and their environment. The content of the support function varied, but the fathers emphasized psychological support, making adjustments in everyday life, interest and presence as important elements. In this phase, the fathers had needs for information about the child’s development, changes in the mother and what they could expect in the time ahead. The Internet was described as the primary source for information, followed by the partner, and finally friends and family. Many questions were inadequately communicated, further reinforcing the uncertainty.

Fathers found their specific role in the pregnancy through “nest-building”. They carried out practical preparations such as adaptations of the home and car, and buying equipment for the infant. Nest-building alleviated some of the feelings of uncertainty and boosted a sense of control. Being prepared and being able to provide the best possible physical conditions for the child resulted in a sense of coping. “I could do practical things that were what I could work on.” Ultrasound examinations gave more substantial form to the pregnancy and confirmed the existence of the child.

All the fathers said that they had feelings of dread before the birth, especially related to the uncertainty involved. Fathers who had been shown around the maternity unit in advance and knew what the unit looked like; where they should park and where they should go when they arrived, described a greater sense of preparedness than those who had not participated in a tour of the unit. In this phase, thoughts about the future took shape in the fathers’ minds: their own role, the potential to give the child a good life, being protective, a positive role model and a playful father. They reflected on their own childhood and their relationship with their own father. Many of them had views on the values that they wanted or did not want to pass on.

I think that the fathers of today, the modern dad are keen to be part of it. I know I want that. It’s my child as much as it’s hers.

The fathers expressed a strong desire for an equal role with the mother in the care of the child.

Delivery

Delivery related to the birth itself. The fathers described this as a confirmation and a turning point. All the fathers had positive experiences, even if they had dreaded the event beforehand. In this phase, the men felt that they were important resource for their partners giving birth. Although they felt inadequate when they saw their partner in pain and fear that something might go wrong, they still found it positive to be present and provide support by being there and providing practical care. The limited period made the situation easier to deal with. In this connection, none of the fathers described the women as the most important. The men saw themselves as participating. The childbirth was described as “ours”, in contrast to “her” pregnancy. “It’s as though that’s the time it first dawns on you, that now we are in fact three.” The birth give substance to a new life phase, where the goal of the pregnancy had been achieved and the child was perceived as tangible and real.

Barriers to the fatherhood role

Fatherhood barriers are factors that inhibit the father’s role. Uncertainty about how to handle the child was highlighted as a stress factor. A crying child, difficulties in comforting the child or interpreting its needs and signals resulted in a low degree of coping. Lack of acknowledgement of their role from those around them was also a barrier.

Everything is new and unfamiliar. How are you supposed to hold and carry the child? He is crying! What do I do now? Should he be doing that?

Several of the fathers emphasized the lack of a sense of fatherhood, lack of sleep and a depressed mood as stressful. They described a low level of openness and acknowledgement of feelings other than positive ones. “It is psychologically tiring for the father as well.” Postpartum depression was referred to as a female phenomenon. Only a couple of the fathers had thought that postpartum depression might affect men. They found it difficult to talk about their own psychological challenges, even with their partner. If the mother was tired and low-spirited, the fathers described the initial period as especially difficult. The fathers had generally felt unprepared for how tired the mother could be in the initial period after the birth. Challenges that they described included expectations that they should be present and the lack of time for themselves. The mismatch between taxing new demands in everyday life and the perceived ability to meet these demands was also found challenging. Relational challenges such as strains between the partners and an inadequate network were highlighted as negative.

Everything is new to the father as well. Things change completely. After the first fourteen days, you have to go back to work. The mother expects you to carry on contributing and functioning both day and night. And you need to function on the job, so you end up feeling worn out.

All the fathers experienced both facilitating and inhibiting factors during the early period of their child’s life, but the dominant categories varied.

Facilitators of the fatherhood role

Facilitators are factors that promote the father’s role. During the first months of the child’s life, the fathers transitioned through a period of increasing mastery and confidence. Coping with practical tasks such as changing diapers and feeding was experienced as positive. Getting to know the child, that the child was satisfied and responded as expected, had a facilitating effect. A positive bond between father and child developed through the experience of being able to comfort, calm, protect, respond and get a response. The same applied to the fathers’ experience of themselves as a caregiver on an equal footing with the mother.

I manage to calm and comfort, it’s great. The first time you succeed in calming a crying child is a wonderful feeling.

The fathers experienced bottle-feeding as unequivocally positive. When mothers breastfed their child, fathers often felt overlooked and outside the relationship with the child. In some cases, a certain degree of jealousy was experienced.

We enjoy ourselves when we are feeding. I am very glad we have a bottle-fed baby, so that I have a chance to take part.

The fathers saw the importance of breastfeeding, but were eager to bottle feed, so that they could participate more actively.

When it was the father who had the first contact with the child, for example after a caesarean section, this was described as strengthening the bond. These fathers experienced a sense of fatherhood earlier than if the mother had the first close contact with the child.

I took my clothes off and held the baby skin-to-skin. It was special. Something tangible and real is lying right next to you. You can hear that there is life here!

A good relationship with their partner as well as a shared understanding of caregiving tasks and roles were described as positive. A supportive network was important, especially in the form of family members. Routines, predictability and potential for control over everyday life were facilitating factors in the early period after childbirth.

Discussion

The fathers transitioned from the abstractness of the pregnancy through via concretization through birth to the realization phase in the first months of the child’s life.

The pregnancy

The sense of unreality that fathers found dominant during the pregnancy has also been described in other studies. It seems to be most prominent during the first-trimester of the pregnancy [2,6,9]. Insecurity may trigger increased stress, and many men experience the pregnancy as the most stressful period in the transition to fatherhood [2]. The stress may be associated with psychological reorganization, feelings of unreality, changes in contact with the partner and a change in identity [19]. In this phase, many men primarily perceive themselves as a source of support for the pregnant woman and secondary to the woman as a parent [9,11]. This contrasts with their strong desire to be on an equal footing with the mother when the child is born. The environment often reinforces this secondary role through expectations that the father will primarily support the mother [11].

Fathers often defined pregnancy in terms of the mother’s state of health. Studies place this in the context of the distance and the secondary role that men often experience [9,11]. The man’s role transition is often overshadowed by the woman’s, and men need time and an opportunity for increasing their awareness in this phase so that they can develop their own fatherhood role [11]. Ultrasound during the pregnancy concretized and reinforced a sense of reality. The child became more perceptible and easier to relate to. Several studies specifically describe ultrasound in the pregnancy as a turning point for the man [6,9]. It is therefore important for fathers to participate in ultrasound examinations to strengthen their engagement and their bond to the unborn child. Research confirms that fathers who become engaged early in the pregnancy experience an easier and better role transition [20].

Manageability and control were factors important to the sense of mastery during the pregnancy phase. Several fathers achieved this through preparations and carrying out practical tasks. Preparing the home, car and baby equipment were important coping tasks that increased control, and the fathers had a positive focus on these jobs as their responsibility. Practical control is also described as a facilitating factor in other studies [9]. To some extent, the pregnancy was also marked by anxiety, fear and helplessness. The fathers described many ambivalent emotions and limited understanding of the changes that the pregnant woman was undergoing. Research shows that a lack of knowledge about pregnancy and childbirth as well as a low degree of social support may increase these feelings. Men have also described the pregnancy as lonely, with little opportunity to talk about their own emotions [2,9].

Studies show that if men are offered appropriate information and support from health professionals during the pregnancy, this is regarded as positive and provides an opportunity for inner reflection and a strengthened fatherhood role [3,11]. This should therefore be available early in the pregnancy. It is concerning that none of the fathers in this study highlighted the health service as a source of information, but preferred the Internet as their primary source. This shows that the health services should work to strengthen their position as knowledge providers to fathers-tobe. Where expectations during the pregnancy matched the experience after childbirth, greater mastery of the role was described afterwards.

Childbirth, a concretization

The fathers in the study described the birth as a turning point, in which the experience of childbirth reduced earlier stress and negative expectations. The father’s role became concrete, delimited and more manageable. The opportunity to provide mental and practical support to the mother during the delivery reinforced the father’s own role in a positive way. Again, concrete tasks were emphasized as important for a sense of mastery. In this phase, fathers changed their role description from passive to active, from observing to participating. Other studies provide support for this description of the childbirth experience, in which fathers perceive the birth as tiring and mentally exhausting, and alternate between euphoria and worry [3,11].

Research has shown higher levels of stress in fathers where the delivery was by caesarean section than for vaginal delivery [11]. In this study, however, fathers described the stress level as the same for both modes of delivery. The fathers who had the first close contact with the child after a caesarean section described a stronger bond, more rapid development of a sense of fatherhood and greater closeness to the child afterwards. These positive descriptions are consistent with other research [21]. Early skin contact with father should therefore be emphasized to a greater extent in maternity units, to facilitate bonding with the father and a sense of fatherhood.

The initial period

The neonatal period was again marked by uncertainty. The study identified facilitating and inhibiting factors that influence the development of the fatherhood role. The development of the role was not static, but in constant transition between facilitating and inhibiting tendencies. The factors relate to both comprehensibility and manageability of their own and the child’s situation, and experience of meaningfulness in their new role [10]. The way that fathers described fatherhood three to four months after the birth depended on the factors that were dominant. Manageability referred to practical tasks around child care, emotional balance and control over everyday life. Fathers who participated actively in practical care at an early stage mastered the role more quickly.

Breastfeeding resulted in distance to the father and the father’s highlighted bottle feeding as unequivocally positive. Being able to fulfil the child’s primary needs strengthened the bond between father and child, as did early skin contact and personal time with the child. This is also consistent with other research [21]. The child’s response through smiles, contact and ability to be comforted facilitated the sense of fatherhood. The neonatal period involves biological and psychological changes for both parents. The oxytocin level rises in both sexes and is further strengthened by positive contact and interaction with the child [22].

Consistency between everyday demands and manageability in the first months of the child’s life was vital. Several studies confirm that excessive everyday demands and a lack of balance between work outside the home, household responsibilities, respite for the mother and a desire for personal time can be experienced as overwhelming [3,23]. The experience of meaningfulness can nevertheless compensate for a lower degree of manageability.

Mental health

Postpartum depression may also affect fathers. Some of the fathers experienced psychological stress and described their own mental health in terms consistent with symptoms of depression in men [1,12,24] even though none of the men defined this as depression. Studies show increased rates of depression in men during the child’s first year of life, with the highest levels three to six months after childbirth [12]. Some studies show a moderate correlation between maternal and paternal depression [12], while others show a clear increase in risk for the father if the mother is depressed [24]. The fathers in this study experienced extra challenges when their partner had mental health problems. From the perspective that this is a taboo topic that receives little attention postpartum depression in men represents a challenge, with a risk of higher prevalence than has been registered [12,24]. Parents with depression have a generally high level of parental stress and less emotional attachment to the child [24], which the fathers in this study also describe. Prevention and treatment of postpartum depression should focus on both parents [12]. Despite increased prevalence of depression, fathers generally experience better mental health in the child’s first years than men who are not fathers [22].

Strengths and Limitations

The fatherhood role has previously received little attention in Norwegian studies. The main findings in this study are supported by findings in international research, but also have new dimensions. All nine informants had a relatively similar sociocultural background, age and life situation. The findings are therefore not generalizable. Use of the interview guide ensured a consistent approach. Open questions increased the informants’ opportunity to communicate their own story. The findings are strengthened by the participants’ first-hand knowledge of the topic. The interviewer was a public health nurse, which involves some previous knowledge [15] and may have influenced the interviews, even though efforts were made to achieve neutrality.

Conclusion

Fathers’ experience of the transition and development of the fatherhood role was a process in which the man transitioned from relating to the abstractness of pregnancy through the concretization of childbirth to the realization phase after birth. A variety of factors may facilitate or inhibit the development of a positive fatherhood role, where the overall effect of the factors is crucial. How fatherhood is perceived depends on the extent to which men experience mastery and meaningfulness in relation to the child, control and balance in demands and a sense of manageability. Insight into the fatherhood role is important to enable health professionals to provide personalized follow-up of high quality in the health services. Better follow-up will enable public health nurses and midwives to strengthen the role of both the individual father and the family as a whole. This will in turn contribute to better health and development for the child.

22844

References

- Brudal LF (2000) Mental health during pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Condon JT, Boyce P, Corkindale CJ (2004) The first-time fathers study: A prospective study of the mental health and well-being of men during the transition to parenthood. Aust N Z J Psychiatry: 56-64.

- Deave T, Johnson D (2008) The transition to parenthood: What does it mean for fathers? J Adv Nursing 63: 626-633.

- Misvaer N, Lagerlov P (2013) Handbook for child health centers 0-5 years. Oslo: Kommuneforlaget AS (in Norwegian).

- Reform Resource Center for Men (2008) The father does-perspectives on men and care in Norway. Oslo: Reform.

- Chin R, Daiches A, Hall P (2011) A qualitative exploration of first-time fathers' experiences of becoming a father. Community Practitioner 84: 19-23.

- Norwegian Directorate of Health (2016) National professional guideline for health promotion and prevention work in child health center, school health services and health care center for youth. IS-2582.

- Norwegian Directorate of Health (2014) National professional guidelines for maternity care. New life and safe postnatal care for the family. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet.

- Finnbogadottir H, Svalenuis EC, Persson E (2003) Expectant first-time fathers' experiences of pregnancy. Midwifery 19: 96-105.

- Antonovsky A (1987) The mystery of health. The salutogenic model. [Helsens mystery. The salutogenic model]. Oslo: Gyldendal akademisk.

- Premberg A (2011) First-time fathers experiences of parenting, childbirth and first year as father. Gothenburg: Sahlgrenska Academy, Department of Health Sciences, University of Gothenburg.

- Paulson JF, Bazemore SD (2010) Prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers and its association with maternal depression-a meta-analysis. JAMA 303: 1961-1969.

- Madsen SA, Juhl T (2005) Men and postpartum depressions, a guide to the work with men and mental health during pregnancy, childbirth and infancy. In: Rikshospitalet, (ed) Copenhagen: Rikshospitalet.

- Skjothaug T (2016) Fathers' role in the child's early development. In: Holme H, Olavesen ES, Valla L, Hansen MB (eds) Health center service. Oslo: Gyldendal Academic. pp: 35-97.

- Malterud K (2011) Qualitative methods in medical research. 3rd edn. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Kvale S, Brinkmann S (2015) The qualitative research interview. 3rd edn. Oslo: Gyldendal Academic.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B (2004) Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today 24: 105-112.

- NESH (2016) Ethical guidelines for research in social sciences, humanities, law and technology. Oslo: The National Research Ethics Committees.

- Genesoni L, Tallandini MA (2009) Mens psychological transition to fatherhood: An analysis of the literature 1989-2008. Birth 36: 305-318.

- Draper J (2002) It's the first scientific evidence': Men's experience of pregnancy confirmation. J Adv Nursing 39: 563-570.

- Chen EM, Gau ML, Liu CY, Lee TY (2017) Effects of father-neonate skin-to-skin contact on attachment: A randomized controlled trial. Nursing Res Practice 2017: 1-8.

- Gordon I, Zagoory-Sharon O, Leckman JF, Feldman R (2010) Oxytocin and the development of parenting in humans. Biol Psychiatry 68: 377-382.

- Chin R, Hall P, Daiches A (2011) Fathers' experiences of their transition to fatherhood: A metasynthesis. J Reproductive Infant Psychol 29: 4-18.

- Goodman J (2003) Paternal postpartum depression, its relationship to maternal postpartum depression and implications for family health. J Adv Nursing 45: 26-35.