Sophia Stasi1*, George Papathanasiou2, Myrsini Anagnostou3, Antonios Galanos4, Eustathios Chronopoulos5, Panagiotis I. Baltopoulos6, Nikolaos A. Papaioannou7

1PT, MSc, Laboratory Associate Lecturer of Physical Therapy Department, Technological Educational Institute of Athens (TEI-A), Greece

2PT, MSc, PhD, Associate Professor, Associate Director of Physical Therapy Department, TEI-A Greece

3Physical Therapist, Greece

4MSc, PhD, Biostatistician, Laboratory Research of Musculoskeletal System, Medical School, University of Athens (UOA), Greece

5MD, Assistant Professor in Orthopaedic, Medical School, UOA, Greece

6MD, Coordinator Director of the A’ Orhtopaedic Department “KAT” General Hospital, Associate Professor in Functional Anatomy, Director of the Sports Medicine Laboratory, Faculty of Physical Education and Sport Science, University of Athens, Greece

7MD, Associate Professor in Orthopaedic, Director of Laboratory Research Musculoskeletal System, Medical School, UOA, Greece

*Corresponding Author:

Sophia Stasi

30 Ouranias street, GR-14121

Athens, Greece

E-mail: soniastasi1@gmail.com

Keywords

Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS), item analysis, reliability, convergent validity

Introduction

Functional ability refers to an individual’s ability to perform the activities and tasks of daily living that are required in order for him/her to cope with personal and environmental demands [1]. A reduction in functional ability represents a decrease in well-being and is directly associated with a degraded quality of life. Health care professionals recognize the importance of improving patients’ quality of life; thus, the ultimate purpose in any conservative or surgical intervention is to maintain or enhance patients’ functional ability based on the individual’s activity profile. Evaluation of functional ability is essential in clinical practice. The level of functional ability, or disability, determines the decision making process and sets the goals of therapeutic intervention. In addition, the functional assessment is used to assemble epidemiological information for specific population groups and to collect data on the overall level of functionality in order to enable the most effective treatment planning.

The use of rating scales and questionnaires contributes to the objective documentation and recording of the collected findings. Also, such instruments can be used as ongoing measures of functionality throughout the treatment period. There is a variety of rating scales, such as specific questionnaires for a particular musculoskeletal disease or for one single joint. These instruments usually record symptoms, range of motion limitations and/or functional capabilities. Among those, the Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS) [2] is a specific questionnaire that evaluates the functional ability of an individual with a lower extremity musculoskeletal disorder.

The LEFS, which was introduced in 1999 by Binkley et al, [2] is a reliable, valid and responsive instrument applicable to patients with a wide spectrum of lower extremity disorders of musculoskeletal origin [3-11]. The LEFS has been used for measuring the activity limitation and the functional outcomes in research projects related to patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee undergoing total joint arthroplasty, [3,4] after hip fracture, [5] with anterior knee pain, [6] after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, [7] with ankle sprains, [8] with ankle fractures, [9] with post-traumatic distraction osteogenesis, [10] and for inpatients of orthopaedic rehabilitation wards [11]. Hart et al [12] reported that functional status, as assessed using LEFS scale, represents the “activity dimension” of the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. To our knowledge, there are only two questionnaires that have been officially translated and standardised into Greek and that can be used in the assessment of the musculoskeletal system: the SF-36 Health Survey (IQOLA SF-36 Greek Standard Version 1.0) [13,14] and the Standardized General Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire [15]. Globally, SF-36 is considered to be the “gold standard” assessment tool, although it is a generic questionnaire that assesses the overall health status of the patient, including social, emotional and physical status. The original Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire [16] was developed to analyse musculoskeletal symptoms such as ache, pain or discomfort. However, this instrument is not specific for the lower limb and does not evaluate the functional status of the patient. Therefore, there is a lack of a worldwide accepted rating scale, adapted to the Greek language, for the evaluation of patients with lower limb musculoskeletal disorders.

The purpose of this study was to construct a Greek version of the Lower Extremity Functional Scale and to evaluate its reliability in relation to Greek individuals with lower extremity musculoskeletal disorders. Specifically, we set out to conduct an LEFS-Greek item analysis, assess the questionnaire’s repeatability, and test its convergent validity. In addition, a broader awareness and use of the LEFS instrument in the Greek setting would facilitate objective comparisons between studies and contribute to the validity of future meta-analyses.

Methods

Cultural adaptation

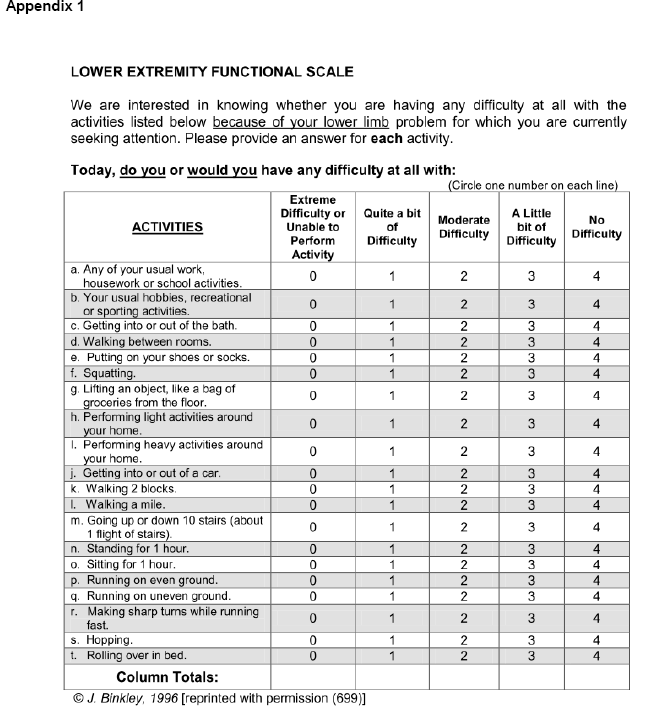

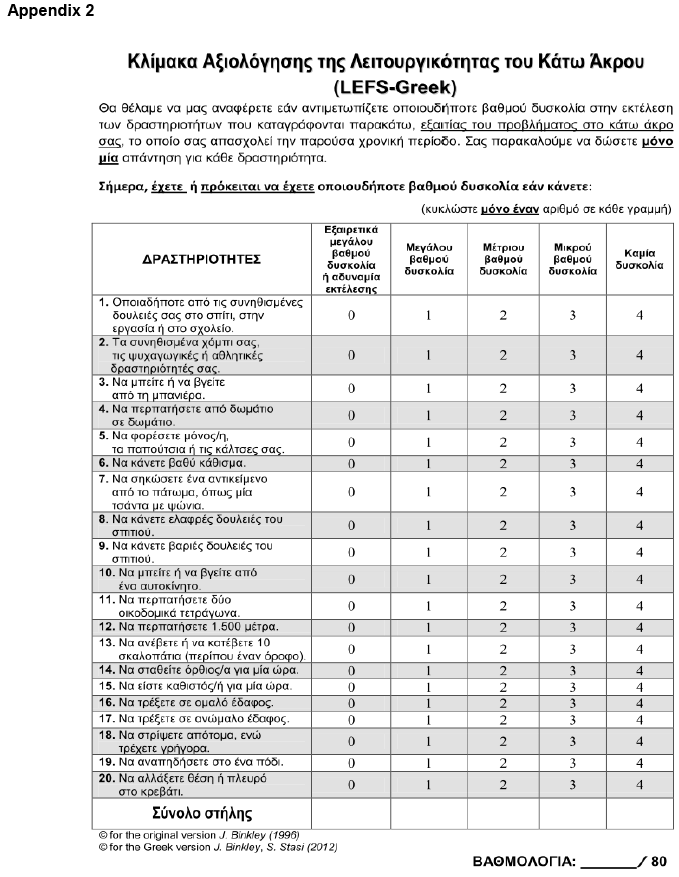

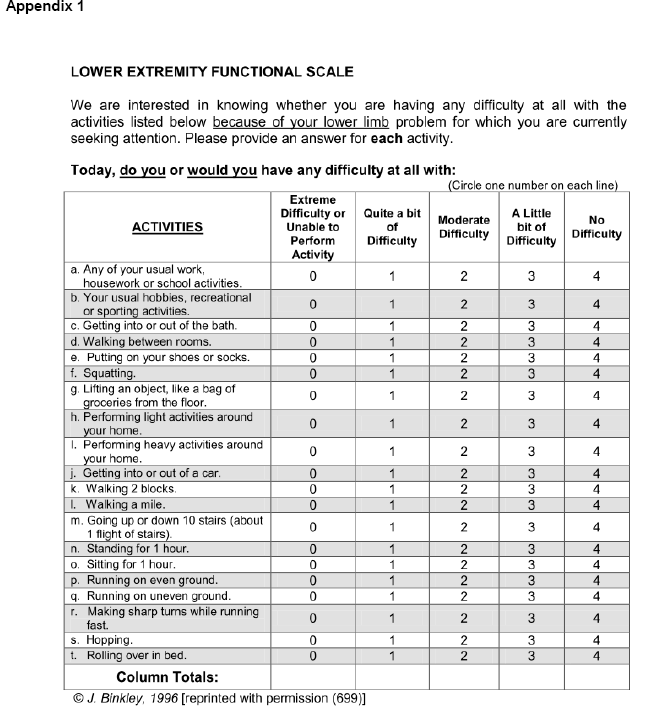

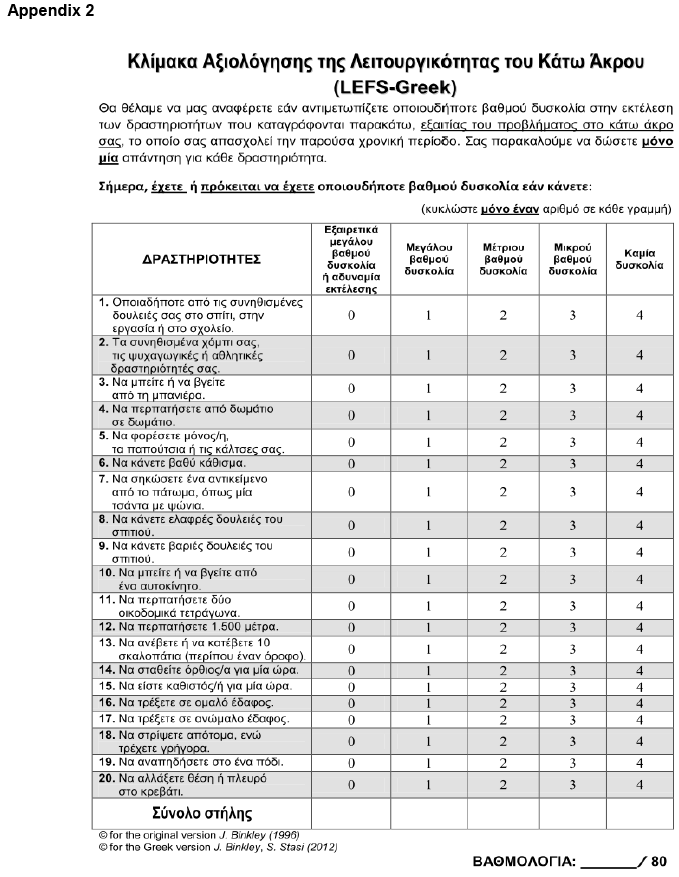

The LEFS is a functional status questionnaire that aims to investigate the degree of difficulty a patient experiences in performing everyday tasks, due to disorders of his/her lower extremity. The LEFS consists of twenty items, each of which is scored on a 5-point scale (0 to 4) (Appendix 1). The equivalence between the individuals’ response options and the scale points is: 0 = extreme difficulty or unable to perform activity; 1 = quite a bit of difficulty; 2 = moderate difficulty; 3 = a little bit of difficulty; 4 = no difficulty. A sub-score, termed “column total”, is derived by adding the scale points vertically. The four column totals are added horizontally to give the total LEFS score, with minimum value 0 and maximum 80.

The adaptation of LEFS into Greek followed the guidelines developed by Guillemin et al [17,18] and Beaton et al [19]. Official permission for reprinting and translating the original LEFS questionnaire was given by Dr. Jill M Binkley. A team of experts, consisting of health science professionals, a biostatistician and two bilingual non-medical specialists, took care of all the required procedures. These included the translation, the development, the back translation and the initial field-testing phases. Technical, linguistic and cultural adaptations were agreed in a consensus meeting. During this phase, it was decided to use numbers instead of English letters for numbering the items and in item 12 to change the unit of distance measurement from miles to metres. The Greek LEFS was back-translated to check for conceptual equivalence, acceptability and adaptation of wording to the target population. No conceptual differences were noted between the two versions. Field-testing of the provisional version included its completion by three small groups of individuals (n=15) of the same target population group, by means of one-to-one interviews, in order to examine the potential distribution of responses, check comprehension, and to ensure linguistic and content validity. Ultimately, the final version of the Lower Extremity Functional Scale in the Greek language (LEFS-Greek) was constructed (Appendix 2).

Study population

One hundred and forty community-dwelling elderly men and women (aged 65 years and over) randomly selected from five municipal “Open Care Centres for the Elderly” were invited to participate in the study. The main inclusion criterion was the existence of symptomatic lower extremity musculoskeletal conditions that affected only one limb. The term “symptomatic musculoskeletal condition” is used to identify any functional limitation due to chronic bone or muscle pain and/or signs of limited motion to the affected hip, knee or ankle joint. The diagnosis confirming the existence of “musculoskeletal conditions” had to have been recorded in the individual's health card by an orthopaedic doctor. Exclusion criteria were the presence of rheumatic diseases leading to secondary osteoarthritis, musculoskeletal symptoms due to neurological aetiology, and metabolic diseases of the musculoskeletal system. None of the participants had undergone any prior osteotomy or joint replacement surgery.

Thirty-one individuals of the 140 were excluded on the basis of the exclusion criteria and 8 subjects did not turn up on the reassessment evaluation day (day-8). Finally, 101 individuals (40 men and 61 women) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and completed all assessment protocols. The size of the sample followed the recommended “rule of 100” for scale validation studies [20-22]. The non-participants’ demographic characteristics were similar to those of the subjects participating in the study. The data were collected from February until October 2011. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study protocol was approved by the Council of the Physical Therapy department of Technological Educational Institute of Athens and followed the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

Procedures

At initial assessment (day-1), the Greek version of the self-reporting LEFS questionnaire was given to all participants and completed on site, under the supervision of the same member of the research team. LEFS-Greek was re-administered to all participants by the same examiner seven days after the first appointment day (day-8). Between assessments, no variation in individuals’ clinical status was recorded and no treatment interventions were received.

Data analysis

All analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). The critical level for significance was set at p<0.05. Distribution and normality of the collected data were tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and probability-probability plots [23].

Item analysis of LEFS-Greek was used to examine the variability among the 20 items (observed variables) and to identify if any item on the questionnaire did not have a positive monotonic trace when plotted against the total score [24]. Item analysis was carried out using the mean and standard deviation data of the LEFS-Greek items from the initial assessment (day-1).

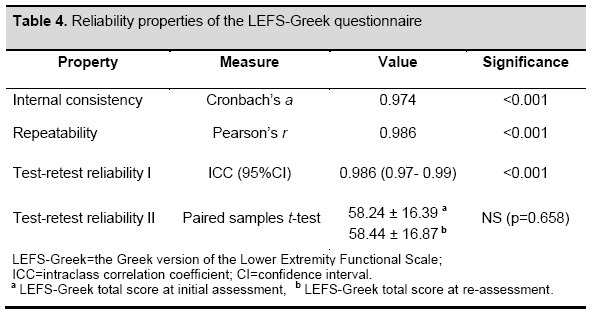

The reliability of LEFS-Greek was evaluated by assessing the instrument’s internal consistency, repeatability and its test-retest reliability. Internal consistency evaluates how well different questions (items) that test the latent structure of the instrument should give consistent results [25]. The internal consistency of LEFS-Greek was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (Cronbach’s a) [26] using the data obtained from the initial LEFS-Greek assessment. A threshold value of 0.70 was chosen, which indicates sufficient reliability for research purposes [27,28]. In the present study, the “Cronbach’s a if item deleted” was used as an additional evaluation test of the LEFS-Greek internal consistency [29]. Repeatability was defined as the stability of participants’ responses over time, that is, the ability of the instrument to give consistent results whenever it is used [30]. The LEFS-Greek repeatability was determined by calculating Pearson’s product moment correlation coefficient (Pearson’s r) between the initial and re-assessment total scores of the LEFS-Greek questionnaire. The Pearson correlation coefficient values were specified as follows: 0.00-0.19 = very weak correlation; 0.20-0.39 = weak correlation; 0.40-0.69 = moderate correlation; 0.70-0.89 = strong correlation; and 0.90-1.00 = very strong correlation [31]. The test-retest reliability of the instrument was defined as the degree to which the participants maintained their opinion in the repeated measurements of the LEFS-Greek questionnaire, taking into account the error in measurements as a proportion of the total variance. Test-retest reliability was evaluated using the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) with 95% confidence interval (CI). The ICC, which is the most suitable statistical test for the assessment of reliability, [32-34] ranges from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating perfect reliability. The Cronbach’s a and ICC correlations were characterized as follows: 0.00-0.25 = little, if any, correlation; 0.26-0.49 = low; 0.50-0.69 = moderate; 0.70- 0.89 = high; and 0.90-1.00 = excellent.35 In addition, the scores of the two assessments were tested for systematic differences using the paired t-test, because the ICC does not correct for systematic differences and agreement by chance.

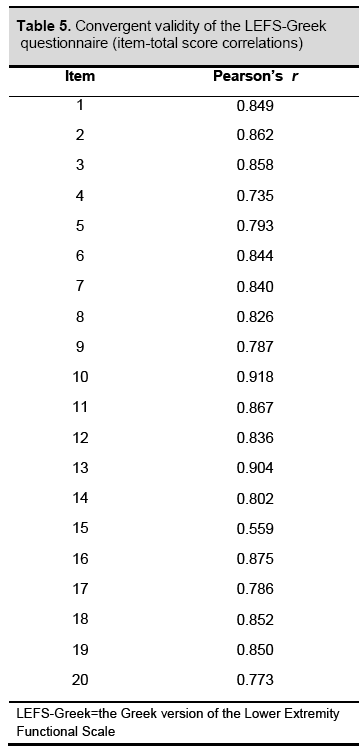

Finally, the convergent validity of LEFS-Greek was evaluated by examining the correlations between the total score of the scale and the item scores, at initial assessment. Acceptable convergent validity should be indicated by high or excellent (0.70 to 1.00) item intercorrelations for all item pairings. This would provide evidence that all twenty items of LEFS-Greek are related to the same construct [36].

Results

Descriptives

The LEFS-Greek inferential statistical analysis using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and probability-probability plots showed a normal data distribution (D [101] = 1.56, p=0.015).

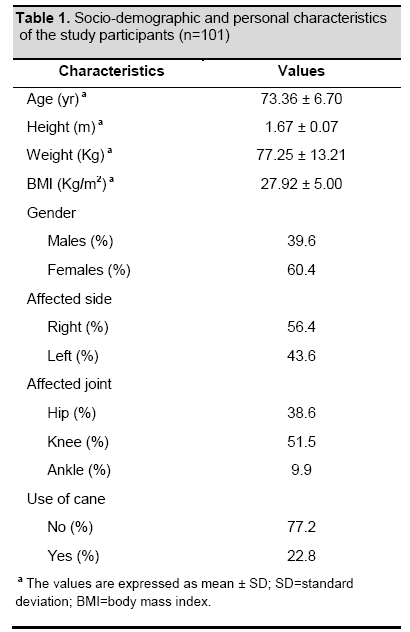

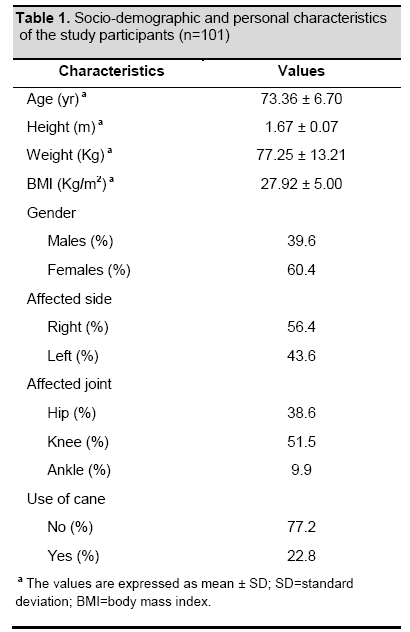

One hundred and one community-dwelling people participated in our study. Table 1 shows the socio-demographic and personal characteristics of the participants. The mean age of the subjects was 73.36 years (65-95), 39.6% were males (n=40) and 60.4% were females (n=61). The musculoskeletal disorder involved the right lower limb in 56.4% of the participants and the left lower limb in 43.6%. In 38.6% the musculoskeletal disorder affected the hip joint, in 51.5% the knee joint, and in 9.9% the ankle joint.

At initial assessment, one hundred and one participants completed the questionnaire. The mean LEFS-Greek total score was 58.24 (SD ± 16.39), ranging from 4.00 to 78.00. There were no missing items for LEFS-Greek score. There were no floor or ceiling effects, since none of the participants scored the worst (0) or the best (80) possible total score. At the second administration (day 8), all participants completed the questionnaire and the mean LEFS-Greek total score was 58.44 (SD ± 16.87), ranging from 5.00 to 76.00.

Item analysis

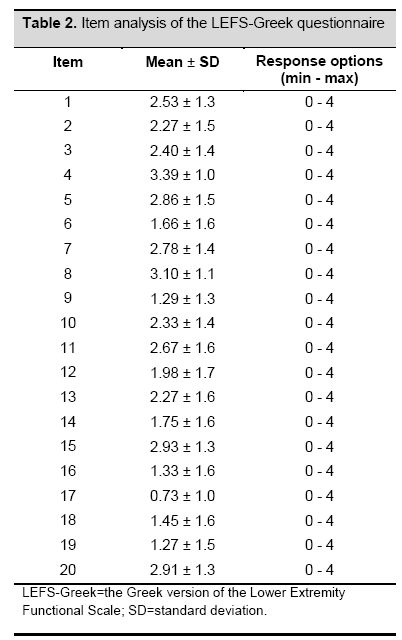

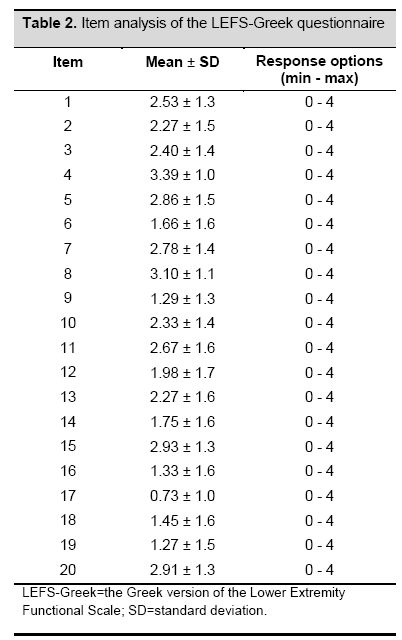

Item analysis for the 20-item LEFS-Greek instrument demonstrated that all items had a positive monotonic trace when plotted against the total score. Item analysis statistics are presented in table 2, with item means (average response for each item) ranging from 0.73 (item 17) to 3.39 (item 4). There was good variability in relation to the means (SDs ranged from 1.02 to 1.70).

Reliability

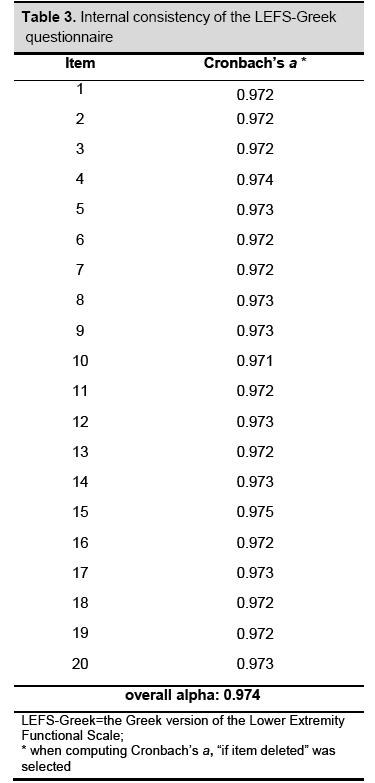

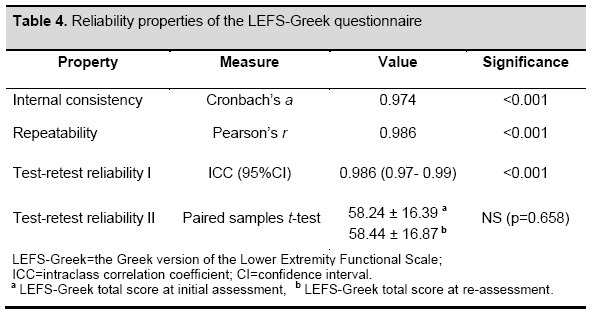

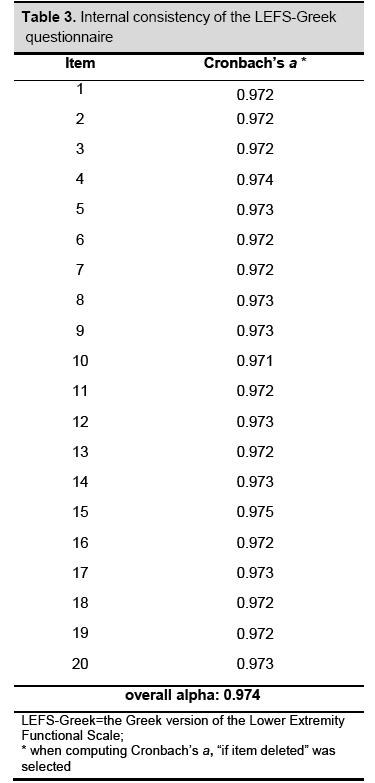

The internal consistency of LEFS-Greek was excellent, with an overall Cronbach’s a at 0.974, ranging between 0.971 (item 10) and 0.975 (item 15) (Table 3). All values were higher than the chosen threshold value of 0.7, suggesting that all LEFS-Greek items are interdependent and homogeneous in terms of the construct they measure. The paired samples t-test between the LEFS-Greek total score at initial assessment and re-assessment indicated no statistically significant differences, (p=0.658, Table 4). Pearson’s r and the ICC coefficient revealed excellent correlations between initial assessment and re-assessment (0.986 and 0.986 respectively, p<0.001, Table 4). Our results indicated that the total score of LEFS-Greek was remarkably consistent between the two measurements.

Convergent validity

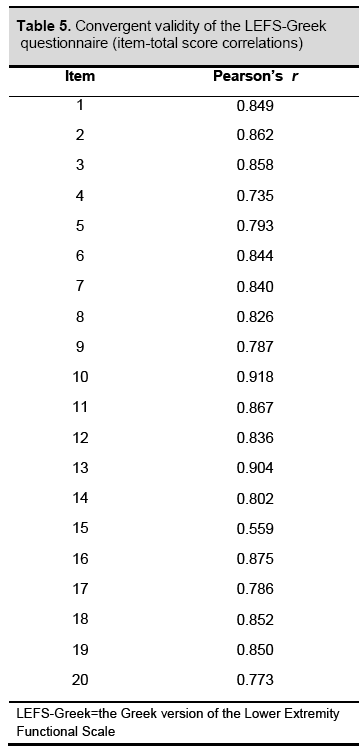

Table 5 summarises the correlations between the LEFS-Greek total score and the item scores of the questionnaire at initial assessment (items - total score correlations). All items showed high or excellent correlation coefficients, with the exception of item 15 (= 0.559), ranging from 0.735 (item 4) to 0.918 (item 10), indicating that LEFS-Greek items were strongly related to the same construct.

Discussion

This is the first study to examine the reliability properties of the LEFS questionnaire in a Greek population cohort. The constructed Greek version of LEFS was tested in community-dwelling elderly people with lower extremity musculoskeletal disorders and was found to have remarkable internal consistency, excellent repeatability, very high test-retest reliability and strong convergent validity properties.

Item analysis

Item analysis was used in order to determine the participants’ level of functional ability. By examining the mean values of the responses in every LEFS-Greek item, the functional limitations of the selected population group were studied. Specifically, in higher intensity level and demanding activities, such as running on uneven ground, hopping on one leg, and performing heavy activities around their home, most of our subjects responded that they had quite a bit of difficulty or extreme difficulty. In contrast, in lower intensity level and less demanding activities, such as performing light activities around their home, putting on shoes or shocks, and walking between rooms, most of the participants responded that they had little or no difficulty. The low mean values of the responses in items concerning higher intensity levels and more demanding activities, and vice versa, could be explained by the fact that our selected population group was comprised of elderly people.

Reliability

Our results indicated that LEFS-Greek was consistent, stable and highly repeatable between the two assessments. Analysis of the internal consistency of LEFS-Greek showed that the twenty items of the scale satisfactorily measure all aspects of the participants’ functional ability. The LEFS-Greek overall Cronbach’s a coefficient was similar to those of the original version (0.96)2 and the Italian version (0.94), [37] altogether indicating an excellent internal consistency for the LEFS scale. During the calculation of “Cronbach’s a if item deleted”, only one item (item 15) was found to have a value higher than the scale’s overall Cronbach’s a. This difference was only one thousandth (0.001), a very small deviation from the overall alpha, and it was not considered significant [26,38]. In line with our results, Cacchio et al reported that no item was found to change substantially the internal consistency of the Italian version of the LEFS scale [37]. The values of Pearson’s r indicated excellent repeatability of an individual’s response over time. The LEFS-Greek questionnaire's test-retest reliability was found to be very high, with a low standard error of measurement, in line with the results of Binkley et al2 for the original version (0.86) and those of Cacchio et al37 for the Italian version (0.91).

Convergent Validity

The items-total score correlations of LEFS-Greek provided evidence that all twenty items converge on the same construct. However, one item (item 15) exhibited a moderate correlation coefficient (0.559), while all other items had high or excellent values. The same item 15, which investigates the individual’s capability of sitting for 1 hour, was the only one to have a value higher than the overall Cronbach’s a, though only by one thousandth, as mentioned above. These two findings could related to the fact that, during the completion of the questionnaire, most of the participants asked for clarification before answering item 15. Specifically, they asked whether they were allowed to stretch their legs while in the seated position or whether their knee joints had to remain in flexion. Since the original instrument was not specific concerning the proper position of the subjects’ lower limbs, all participants were told to answer item 15 according to their own interpretation of the question.

Strengths and limitations

The standardized methods that were used in all phases during the cross-cultural adaptation of the original LEFS scale and the random selection of the participants from a well-defined and homogenous target population are important strengths of this study. In addition, testing the reliability of the LEFS-Greek instrument using four standardised statistical measures added statistical power to our results. However, there is a potential limitation associated with the present study; LEFS-Greek was examined for reliability only in older age groups. Therefore, it remains necessary to extend the study of the instrument’s clinimetric properties to other specific age and musculoskeletal disability groups. The study design did not include the validity analysis of the questionnaire or an examination of the responsiveness of LEFS-Greek. Documentation of the validity properties of the LEFS-Greek questionnaire is the purpose of an ongoing study by the same research team (Stasi S, Papathanasiou G, et al, in preparation).

Conclusion

In the present study, the LEFS-Greek questionnaire was used to evaluate the functional ability of community-dwelling elderly people. The instrument demonstrated excellent reliability properties, comparable to those of the original version and its Italian adaptation. Overall, it can be suggested that LEFS-Greek might be a reliable tool for assessing functionality in individuals with lower extremity musculoskeletal disorders.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jill M Binkley, Executive Director of TurningPoint Women's Healthcare, Alpharetta, Georgia, USA for providing the permission to translate LEFS into the Greek language, and Philip Lees, technical editor of the Hellenic Journal of Cardiology, for his invaluable editorial assistant with the English text. We would also like to thank Dimitrios Petropoulos, student of the Physical Therapy Department of the Technological Educational Institute of Athens, Greece for his contribution to the data collection

3120

References

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health Programme. The Role of Physical Activity in Healthy Ageing. https://www.imsersomayores.csic.es/ documentos/ documentos/oms-role-01.pdf (assessed 10 April 2012).

- Binkley JM, Stratford PW, Lott SA, Riddle DL. The lower extremity functional scale (LEFS): scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. PhysTher. 1999; 79(4):371-382.

- Pua Y-H, Cowan SM, Wrigley TV, Bennell KL. The Lower Extremity Functional Scale could be an alternative to the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index physical function scale. J ClinEpidemiol. 2009; 62:1103-1111.

- Kennedy DM, Stratford PW, Robarts S, Gollish JD. Using outcome measure results to facilitate clinical decisions the first year after total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Sports PhysTher. 2011; 41(4):232-39. doi:10.2519/josp.2011.3516.

- Mangione KM, Palombaro KM. Exercise prescription for a patient 3 months after hip fracture. PhysTher. 2005; 85(7):676-687.

- Watson CJ, Propps M, Ratner J, Zeigler DL, Horton P, SmithSS. Reliability and responsiveness of the Lower Extremity Functional Scale and the Anterior Knee Pain Scale in patients with anterior knee pain. J Orthop Sports PhysTher. 2005; 35 (3):136-146.

- Stengel D, Klufmoller F, Rademacher G, Mutze S, Bauwens K, Butenschon K, Seifert J, Wich M, Ekkernkamp A. Functional outcomes and health-related quality of life after robot-assisted anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon grafts. Knee Surg Sports TraumatolArthrosc. 2009; 17:446–455. DOI 10.1007/s00167-008-0700-1.

- Alcock GK, Stratford PW. Validation of the Lower Extremity Functional Scale on athletic subjects with ankle sprains. Physiother Can. 2002; 54(4):233-40.

- Chung-Wei CL, Moseley AM, Refshauge KM, Bundy AC. The lower extremity functional scale has good clinimetric properties in people with ankle fracture. PhysTher. 2009; 89(6):580-588.

- Schep NWL, van Lieshout EMM, Patka P, Vogels LMM. Long-term functional and quality of live assessment following post-traumatic distraction osteogenesis of the lower limb. StratTraum Limb Recon.2009; 4:107–112. DOI 10.1007/s11751-009-0070-3.

- Yeung TS, Wessel J, Stratford P, Macdermid J. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the lower extremity functional scale for inpatients of an orthopaedic rehabilitation ward. J Orthop Sports PhysTher. 2009; 39(6):468-477.

- Hart DL, Mioduski JE, Stratford PW. Simulated computerized adaptive tests for measuring functional status were efficient with good discriminant validity in patients with hip, knee, or foot/ankle impairments. J ClinEpidemiol. 2005; 58: 629–638.

- Pappa E, kontodimopoulos N, Niakas D. Validation and norming of the Greek SF-36 Health Survey. Qual Life Res. 2005; 14:1433-1438.

- Anagnostopoulos F, Niakas D, Pappa E. Construct validation of the Greek SF-36 HealthSurvey. Qual Life Res. 2005; 14:1959-1965.

- Antonopoulou M, Ekdahl C, Sgantzos M, Antonakis N, Lionis C: Translation and validation into Greek of the standardised general Nordic questionnaire for the musculoskeletal symptoms. Eur J Gen Pract. 2004; 10:35-36.

- Kuorinka I, Jonsson B, Kilbom A, Vinterberg H, Biering-Sørensen F, Andersson G, Jørgensen K. Standardized Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. ApplErgon. 1987; 18:233–237.

- Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J ClinEpidemiol. 1993; 46:1417-1432.

- Guillemin F. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of health status measures. Scand J Rheumatol. 1995; 24:61-63.

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures.Spine. 2000; 25:3186-3191.

- Gorsuch RL. Factor analysis, 2nd edition. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1983.

- Kline P. Psychometrics and psychology. London: Acaderric Press, 1979: p 40.

- MacCallum RC, Widaman KF, Preacher KJ, Hong S. Sample size in factor analysis: The role of model error. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2001; 36:611-637.

- Chakravarti IM, Laha RG, Roy J: Handbook of Methods of Applied Statistics. Vol 1. John Wiley and Sons, New York; 1967:392-394.

- Item Analysis. https://xnet.rrc.mb.ca/tomh/item_analysis.htm (assessed15 March 2012).

- Trochim WMK. Types of Reliability. Internal consistency. 2006: pp1-6. https://www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/reltypes.php (assessed 19 March 2012).

- Cronbach LJ, Shavelson RJ. My Current Thoughts on Coefficient Alpha and Successor Procedures.Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2004; 64(3):391-418. doi:10.1177/0013164404266386.

- Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests.Psychometrica. 1951; 16:297-334.

- Gliem JA, Gliem RR. Calculating, Interpreting, and Reporting Cronbach’s Alpha Reliability Coefficient for Likert-Type Scales. Refereed Paper, In Midwest Research-to-Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community Education, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, 8-10 October 2003, pp 82-88.

- Berg KE, Latin RW. Measurements and data collection concepts. In Berg KE, Latin RW.: Essentials of research methods in health, physical education, exercise science, and recreation. 2nd edition. Baltimore-Philadelphia, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004, p165.

- Fowler J, Jarvis P, Chevannes M. Practical statistics for nursing and health care. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2002.

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979; 86:420-428.

- Dunn G, Everitt B. Clinical biostatistics: an introduction to evidence-based medicine. London, UK: Edward Arnold, 1995.

- Ottenbacher KJ, Tomchek SD. Reliability analysis in therapeutic research: practice and procedure. Am J OccupTher. 1992; 47:10-16.

- Portney L, Watkins M. Foundation of clinical research: applications to practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2000.

- Web center for social research methods. Knowledge base. Convergent & Discriminant Validity. https://www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/convdisc.php (assessed 18 March 2012).

- Cacchio A, De Blasis E, Necozione S, Rosa F, Riddle DL, di Orio F, De Blasis D, Santilli V. The Italian version of the Lower Extremity Functional Scale was reliable, valid, and responsive. J ClinEpidemiol. 2010; 63:550-557.

- Cortina JM. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J Applied Psych. 1993; 78(1):98-104.