Key words

Globalisation, migration, Asia, doctor, nurse

Introduction

International migration of health care workers, mainly from low-income countries, has become a controversial global issue.[1] High-income countries are accused of poaching skilled health workers from developing countries which are struggling to address their own health challenges,[2-3] e.g. one quarter of all Canada’s doctors were trained outside the country.[4]

Although, the issues, patterns and the magnitude of migration vary in different countries, it generally increased in the 1990s along with increasing globalisation and the revolution in information and communication technology.[1-5] Consequently, the poorer countries of Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa are feeling impact of this one-way emigration of trained health workers.[6]

The United Kingdom (UK) is a major destination for health workers from its former colonies, with 49,780 foreign-born doctors (33.1% of medical work force) and 50,564 foreign-born nurses comprising 8 % of the total nurse work force.[7] Source and destination countries are often linked, e.g. the similarity in health care and education systems, as well as language and culture. However, due to the universal nature of health problems and treatment care workers can easily adapt in a new environment.[8]

Many developing countries have underfunded health systems, which have a persistent shortage of medical supplies and equipment, poor physical settings, a lack of incentives, training and skill development opportunities, discriminatory and hierarchical work environments.[9] Moreover, ethnic and political violence in some countries has resulted in displacement, ear and human rights abuses; all factors pushing health workers to emigrate to more peaceful countries.[10] Other pull factors for work-related migration included: better opportunities for highly skilled professionals, socio-economic benefits, opportunities for skill development, general security, political stability, personal safety, better facilities and equipment.[11]

In some countries such as Nepal, the Philippines and Peru, money sent home by the migrated workers, so-called ‘remittances’ contribute to a fair share of the national income. The families who stay behind can be in a better-off position and their local economies often benefit from a so-called spill-over effect.[12]

Skilled migration has left some countries chronically understaffed; the worst case being the Philippines with 30,000 vacancies for nurses and at the same time 150,000 nurses working abroad.[13] This loss of intellectual capital and public investment in education can affect health care systems in the sending countries and can damage their economic development.[14] The migrants may have adjustment difficulties due to a lack of knowledge of new working environment and the legal systems;[15] they may experience discrimination, low pay and may feel and face an insecure future. Thus, in attempt to move away from poor conditions in their home country, migrants may end up in equally dehumanizing conditions abroad.[16]

Emigration from Nepal started after the Anglo-Nepal war of 1814-15, with soldiers (‘Ghurkhas’) recruited into the British Indian army. There are still more than 50,000 Nepalese in the Indian army and 3,500 in the British army.[17] More recently, the Nepalese have been migrating to Southeast Asia, Far East Asia, and the Middle East for semi-skilled and unskilled jobs. India remains the main destination (49-57%),[18] as there are more than 1.3 million Nepalese working in India, and more than 3 million in total working abroad.[19] Remittance contributes as much as 13% of the total GDP (Gross Domestic Product) of Nepal.[17-20]

Sparsely populated, difficult to access rural areas, low economic development and lack of education are major barriers to delivering effective health services in Nepal. Many government health workers are reluctant to work in remote areas, whilst the private sector provides the majority of health services in cities. [21]

The Nepalese Embassy in London estimates that there are about 75,000 Nepalese living in the UK. The rate of migration had increased over the last decade.[21] The Nepalese Doctors’ Association UK estimates that there are about 300 Nepalese doctors currently working in the UK. There are no reliable estimates regarding the number of nurses who have migrated from Nepal. Furthermore, there are limited studies of the Nepalese community in UK.[22]

Aim

The study aims to establish the range of reasons behind migration, to identify push and pull factors for moving to the UK.

Methodology

The study design most appropriate for collecting the personal, economic and social factors that affect migration is in-depth or semi-structured interviews, which can probe into complex issues and relationships. Recruitment of health professionals was based on membership of professional organisations and snow-ball sampling. The study used elements of grounded theory, namely data collection and conceptualization continued until saturation .[23] The interview schedule for any good interview study requires piloting.[24] The interview data were analysed according to the thematic framework. Respondents were guaranteed confidentiality and informed consent was obtained. Since our study did not include patients and it is not a clinical study, no ethical application was required. Moreover, at the time of the study our university did not have its own ethical review board.

Methods

The sample of respondent doctors was recruited through the Nepalese Doctors Association, UK and nurses through a convenience sampling method and snowballing technique. The interviewees were all qualified health workers from Nepal and working in the UK, in various different parts of England, Wales and Scotland. They were selected regardless of age, gender, their current job status or their intention to continue to stay in the UK.

The interviews were conducted either face-to-face or over the telephone, in Nepali language for the ease of the participants and were flexible, relaxed and interactive. We used a semi-structured interview schedule of the major variables and associated indicators. It was piloted on two participants (one doctor and one nurse). The questions covered the reasons and triggers for emigration, health policy and strategy, organisational structure and culture, resource (human, financial and technical) management, safety and security issues as well as the expectations prior to migration and experiences gained in the new society and working environment. Data collection check list was divided in four groups: (a) doctors- all specialities; (b) nurses; (c) auxiliaries; and (d) pharmacists. For example, the following types of questions were asked for doctors working in NHS and Private sector: Why did they migrate? What triggered it? What did they know about UK before migrating? Who decided to immigrate? Did they try for other countries? Why do they work in this part of the country? Had any training in the UK? Is that their first choice? or How long do they intend to stay?

Each interview lasted from one and half hours to two hours, resulting in about 30 hours of recorded interviews altogether. All audio interviews were translated and transcribed into English, which amounted about ten to 15 pages of transcription for each interview. We guaranteed confidentiality and informed consent was obtained before the interviews.

Results

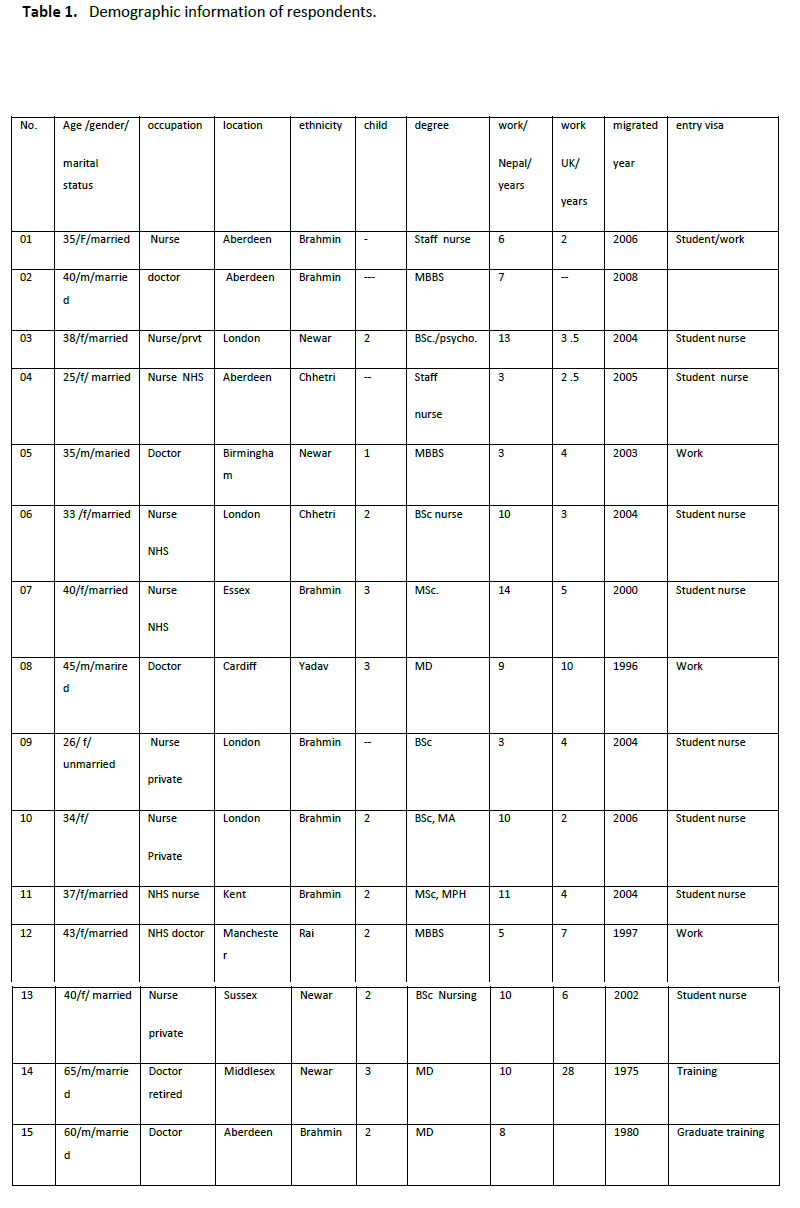

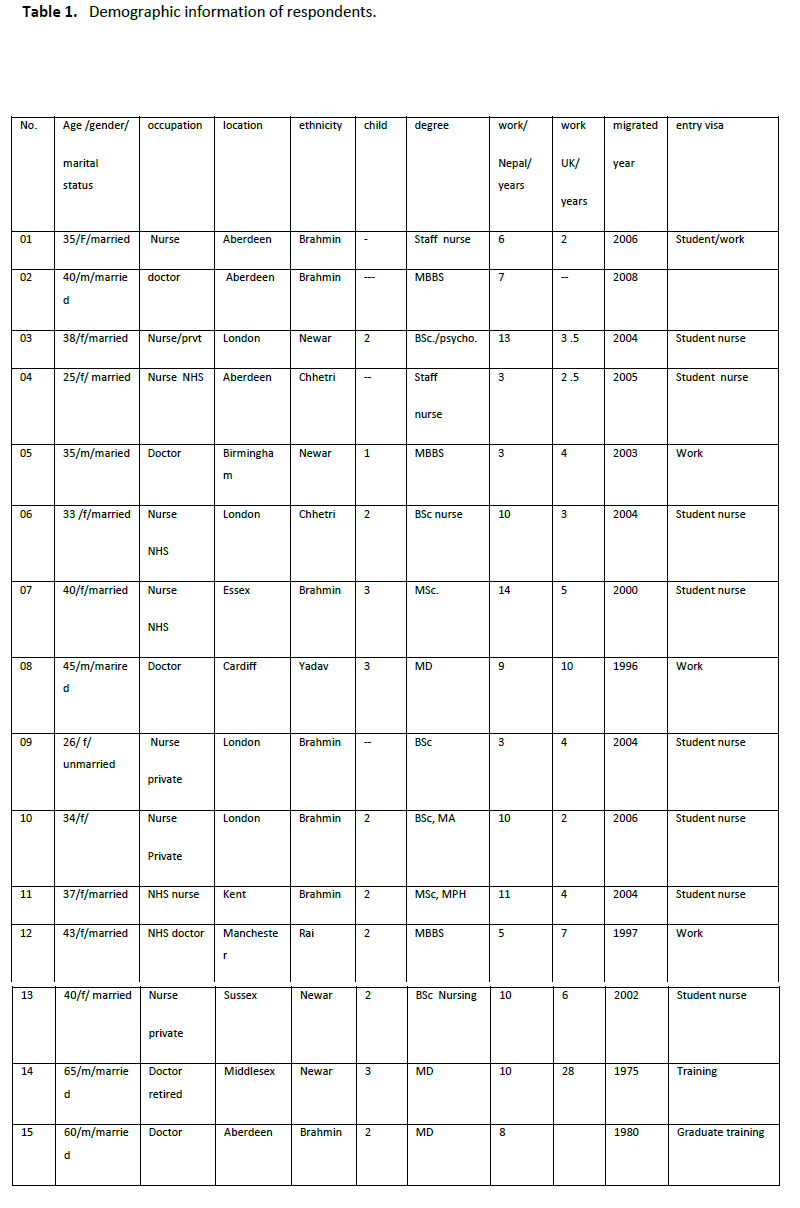

There were 15 interviewees - nine nurses and six doctors. The majority (n= 11) was between 25- 40 years old and only four of them were over 40. The youngest was 25 years old and the oldest was 65. There were ten female interviewees: one doctor and nine nurses; and fourteen interviewees were married. Seven out of fifteen interviewees were from higher castes. Of the nine nurses, seven had university degrees and only two had basic staff nurse education.

All interviewees had practised in Nepal either in government hospitals or in private health services for more than five years. Only one interviewee was retired. Four doctors worked in government health services in the NHS (National Health Service) and one was seeking a job. Five nurses were working in the NHS and four of them in the private sector.

All nurses had entered the UK as student nurses and the doctors had either postgraduate training visas or work permits.

All interviewees were state-funded for their degrees or training in Nepal; and most doctors and nurses had been trained in government-teaching hospitals or nursing colleges. Two doctors had graduated from the All India Medical Institute before there was a medical school in Nepal.

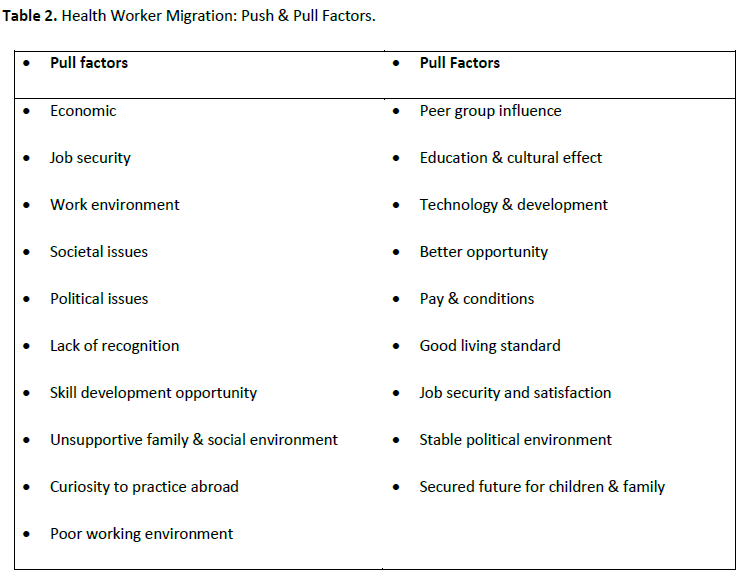

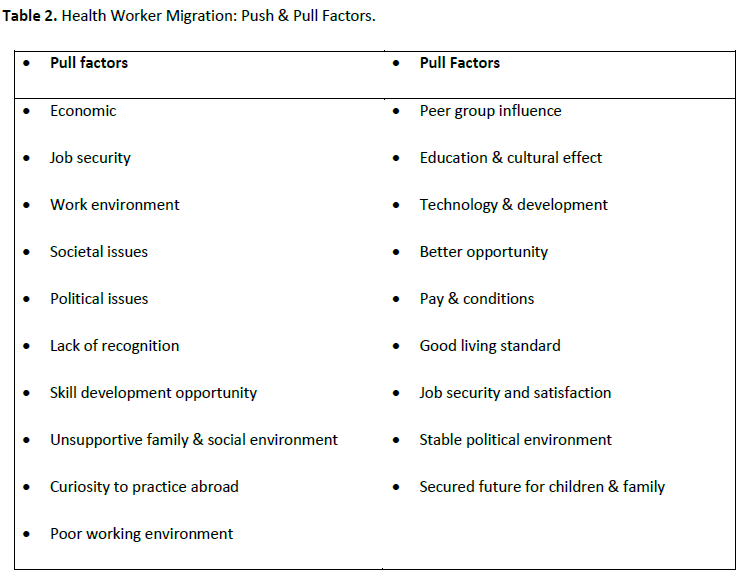

All interviewees had families in the UK, apart from two nurses and ten had children. All were born in Nepal and migrated to the UK to work. Most had a work permit and currently resided in the UK (five of them had British Citizenship). Table 1 highlights the characteristics of the respondents. Whilst Table 2 presents the ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors identified from the in-depth interviews. Each of these issues is outlined in detail below, starting with the push factors.

Push factors

Economic Issues

Low earning was one of the key push factors as they were unable to maintain their desired standard of living with their previous income and they had felt impoverished. For example,

There is a huge economical gap between higher and lower classes, they are impoverished, not enough to maintain themselves and the families. Nurse 2

This also seems to be an obvious comparative factor as there were better alternatives with higher pay and better conditions:

If you have better earning and opportunities elsewhere, then who will stay there? Doctor 1

The pay in developed countries is so high that they could not compare between source and destination countries:

How would you compare a doctor in New York earning a hundred times more than in Nepal? Choice is yours. Doctor 3

Job Security

Most felt insecure in their job in Nepal:

The state has not paid enough attention for the welfare of the health workers. Doctor 5

Alternatively, they blamed the workplace politics interviewees felt they lack job security:

The main thing is the uncertainty whether they would extend my contract. I was feeling insecure even though they were paying me fairly. Nurse 3

On the other hand, they commented negatively on the way jobs were allocated:

Job is always in crisis. No one knows where you will be transferred and what type of situation you have to face ahead, and then we get frustrated. Nurse 8

Workplace Security

Almost all had experienced verbal and physical assaults at work:

If something goes wrong, they (patients or their family) attack you physically. Once I was severely beaten when a patient arrived in hospital in terminal stage, suffering from snakebite and died due to lack of proper medicine, but the mob vandalised the hospital and everybody was severely beaten. Doctor 3

All nurses felt insecure especially at night due to visitors staying overnight:

There are security lapses, especially at night; security provision does not work when it is needed the most. Nurse 2

Most thought that there are efficient health workers in Nepal who accept their responsibility, for example:

Health workers have an important responsibility on their shoulder but no physical security of these professionals who work for humanitarian causes; you have to go for treatment any time anywhere, like a labour pain in the middle of the night in a rural area, cannot stop yourself, and imagine how vulnerable we are in Nepal. Who guarantees our security? Doctor 1

General Security

Nurses especially felt unsafe travelling to and from work, especially at night when there is no light around or no transport available; one nurse had experienced some near misses:

It is appalling; you can be attacked any time. Somebody waiting in the corners to assault, you are in trouble. I have escaped very frightening situations at night, in my own hometown; just imagine how terrified I would be. Nurse 2

Most were worried about the political situation and related unrest and violence:

There is constant instability; everything disrupted frequently, transport for patients, workers, and whole atmosphere agitated. How can you work or get to the hospital risking your own life?- Nurse 3

Political Issues

All worried about the bad political practices and the politics within the health care system, which they saw as one of the major barriers to their professional development:

Health care system and policy are related to the politics; there is no recognition whatever you contribute for the country; there are no fair policies. Doctor 5

It hinders the professional development by unnecessary interventions; set code, no practice. You are not a politician but to follow certain procedures. Nurse 6

Respondents were often bitter about politics around their jobs, which led to dissatisfaction and acted as push towards migration:

Power politics within the health care system severely affected the motivation and enthusiasm to accomplish the responsibilities. As a result, we feel insecure. Doctor 4

I had less backing power then others; as a result, I was intimidated, frustrated and irritated by power and force culture, then I migrated. Nurse 8

One nurse found that she was just supporting the wrong political party:

They thought that I had different political philosophy and excluded from better opportunities. Nurse 2

If the health workers had connections with powerful posts, this would open doors for them:

Political influence determines the future, higher the connection, better opportunity you will have. Doctor 3

A specialist who returned to Nepal after further training abroad could not get work in his specialist area of medicine:

I specialised from UK and returned to work but (they) sent me to the remotest part of the country instructing me that if I denied to go there, I could go anywhere I liked but not in the job. Doctor 4

There is a funding gap, which limits service utilization among the population:

People are helpless in Nepal, cannot pay for the expensive treatment like cancer and have to die in wrong time. Affection does not work; you need money. Nurse 4

Lack of Recognition

The majority lacked proper recognition or rewards, for example:

The frustration leads to aggression and pessimism, rather dissatisfaction, bitter reality; and then obviously you try to find the way out from the existing system. Doctor 1

Why do you rot your life if your skill and efforts have not been recognized? They compare their friends and peers and follow their footsteps. Nurse 5

Being placed in a remote area was often an enormous personal burden:

I was better qualified but degraded, transferred far from the home and kids, inaccessible area, being a woman. How could I cope with the situation and do my job? - Nurse 4

My dreams were shattered, devastated and shocked when I was sent to remote areas, supposed to be posted in a specialist hospital, no light at the end of the tunnel. Nurse 8

Lack of Skill Development

Interviewees commented on the unfair distribution of the limited skill development opportunities and injustice in decision-making.

There is lack of postgraduate trainings and standard to enhance their knowledge and skill. Doctor 5

Some found skill maintenance and professional development impossible in Nepal,

Lack of advanced technology and manpower, I was specialising in diabetes but it was impossible to practise in Nepal. Doctor 1

Especially in the remote areas:

I worked in the remote areas for 10 years and forgotten almost of my knowledge and I had to start from the beginning. Doctor 5

Corrupted attitude and wrong culture

Some were unhappy with the traditional hierarchical system and its associated corruption:

Wrong attitude developed as a culture for generations, dishonesty. Policy makers should change their traditional and hierarchical thinking, if not; the situation will be the same even in the centuries. Doctor 4

Feudalists are always in the high-ranking posts for centuries to run the country. They make policies, which are good for them and ignore the public’s interests. How can you feel safe? Nurse 2

Unfair distribution, corruption in mind and heart of the rulers; if you have political power and influence, then you can achieve everything. There is no access to education from the state funding to the disadvantaged citizens. Doctor 5

Lack of Supportive Family and Social Environment

Most nurses did not manage to earn enough especially if their partners were uneducated.

I was unable to maintain three children and home, did not have supportive hands, and compelled to seek the alternative to maintain the things around. I forgot everything for money. Nurse 6

Nursing profession has a negative image in Nepal although some argued that the potential of foreign employment has changed that image:

(the bad image of) … daughter is spoilt as a nurse and son is spoilt by commerce’, changing as the nurses are employed in the developed countries. Nurse 5

Most have difficulties in convincing ‘uneducated’ family and friends about their nursing work:

Lack of education and poverty, if husband is wise than there is less chance of misunderstanding. Nurse 6

My husband couldn’t understand the flexible nature of the job and started argument, but I had no alternative to look after my kids, I was frustrated; as a result, I was just desperate to get rid of him, divorced. I am much happier now. Nurse 2

Curiosity to Practice Abroad

For some respondents, curiosity or ambitions were the main drivers:

I was curious about new places and systems; learning new things, new life and opportunity in another part of the world, one feels monotonous working and living in a same place, just for the change. Nurse 8

My hidden ambition, to achieve qualification and trainings and foreign experience helped to make my mind up to migrate. Nurse 1

Poor Working Environment

Respondents felt that there was no proper management system for either health workers or patients,

Ethically, the patient should be at the focus, which is limited to words in Nepal. As a patient is forced to have medications, but that is vice-versa in the UK. Nurse 5

There is too much workload, lack of proper management of the procedures, many patients die for no reason. There is no provision of investigation after death. There are no effective legal provisions. Nurse 7

Furthermore, health workers were helpless without proper resources:

You cannot do what you are supposed to do due to shortages of things. Doctor 3

Children’s Education

Some had worked in remote areas in Nepal and were unhappy about their children’s upbringing, as one doctor explained:

I was working in remote area; my little son was surprised to see an electric light and compared a mere light with the sun; shocked with it. There was not a proper environment for children. Doctor 3

Whilst education was another key issue for families with children:

There are not good schools for the children in many parts of the country but only in major towns, which are not even affordable, so I was worried about it. Nurse 4

Pull factors

Interviewees mentioned several factors that attracted (‘pulled’) them to the UK

Peer Group Influence

The majority was influenced by friends and family members who had already migrated and encouraged them to come to the UK. Some examples are:

All my colleagues were working here, they had settled; friends and family encouraged me to try my luck to come to the dreamland of the story. Nurse 7

My family members who worked in the British army influenced me to immigrate to the UK. Nurse 1

My husband forced me to come to the UK to earn a lot of money; friends assured me about a better earning and life. Nurse 8

Education and Cultural Effect

For some, it had been a specific pull from the UK rather than elsewhere abroad; e.g. the language, literature and education system and a historical link:

Nepalese settled here for centuries; there has been circular migration, obviously we feel Britain closer than others. We have influence of British education system in Nepal, as a result, I preferred UK. Doctor 5

Education, literature, long Nepal-Britain relation and colonial cultural effect bring us closer. British have good reputation where they worked and their systems are closer to Britain. They are true to their words and honest and sincere as a result many people believe on them. Britain presents positive history. Doctor 2

Technology & Development

All said that better technology and information systems stimulated them to move to the UK.

Advanced system of working practice, facilitation, information system and technology in the UK are incomparable to the developing countries. System and regulations work here; just do what you are supposed to do with confidence. Doctor 1

We can learn all new techniques here and can apply back home later on. Doctor 5

There are advanced technologies and expert skills; preparations for future and research opportunities are some remarkable factors here. Doctor 3

Better Opportunity

All mentioned seeing various opportunities that led them to emigrate:

There are opportunities to improve and develop knowledge, skills, and speciality but there is no opportunity in Nepal. Doctor 4

One to one dealing techniques are more important than the theoretical aspects, practical and challenging for us. We were less familiar with the real practical things in real time situation in Nepal. Nurse 7

You can enrich your skill or gain more knowledge but important thing is- we move for better. (Interrupted) Doctor 1

Some things were perceived to be better in Nepal though, e.g.:

They just provide certificate here. They emphasize on independent study; if you are behind others than you will get further behind; learning by doing or practice, but back home, they teach us how we should do. Nurse 8

Pay & Conditions

Better working conditions and salaries, and being able to send money home, were key pull factors:

I am happy and satisfied; feel happy with handsome amount to send home. All my frustrations and stresses are released with the money. Nurse 2

We are paid well for the job, skill development and equal opportunities, not big gap between higher and lower ranks in the working environment. Doctor 4

Good Living Standard

All agreed that living standards (including the welfare system) were better in the UK:

There is work and life balance here. Doctor 3

There is free treatment for all, good health care system, strong theoretical and practical ground. No one is denied treatment due to his or her specific characteristics. Evidence based practice and the underlying ideology is better than any health care systems in the world. Doctor 1

Job Security & Satisfaction

Some mentioned job satisfaction and security, and more generally, the UK had systems that worked:

We are properly guided and should strictly follow the code of conducts but not on the basis of how much money one (patient) can spend for the tests and medications; there is good referral system here and job satisfaction. Doctor 4

There is more stress here in the UK but the job is safe and good earning, then better family environment than in Nepal. More you work, more you earn. Nurse 5

Political Environment

All mentioned the stable political situation as well as its equitable and fair system:

There is a stable and strong policy; almost equal pay scale, equal opportunities to enhance your qualifications; then obviously, you feel safe and eager to work. Doctor 5

Fair and equitable treatment, system works here; no one is neglected due to money and other matters. They pay for the services and government pays for the treatments. You do not need to be worried about the care. If you think about the elderly people, they are well cared and treated in nursing homes rather hated and neglected like in Nepal. Doctor 3

Secured Future for the Children and Family

Providing a decent living for one’s family, including children’s safety and education were key pull factors:

Our children’s education is free and family members are safe here. Doctor 3

If I were in Nepal, it would not match my earning level and life standard. Doctor 4

All knew about the demand for health workers in developed countries and the high pay and conditions. Some had tried or considered other countries but opted for the UK. One explanation was that professional registration was regarded easier than in other countries.

There was high demand in the UK, I tried in New Zealand, Australia and USA but I was more attracted towards UK. I packed the things and came here- first come, first served. Doctor 6

There is imbalance of wealth distribution among the developing and developed countries; vast differences in opportunities and standard of life, obviously, everybody wants to move towards the rich countries. Doctor 1

However, all respondents were unhappy with the current UK policy on the health workers who were working here for years but felt neglected and biased. They thought that their lives were in jeopardy as they were alienated from their jobs and society, for example:

They want to evacuate the foreign workers who are working here for years by changing whole regulation against us; obliged to find alternatives to move elsewhere. They put our lives in jeopardy. Nurse 9

We are disconnected from our job back home but the current policy in UK seems adverse to our interest. We are eventually forced to find a safer place somewhere. There are inequalities in work place and wider society in the UK. Doctor 2

Discussion

Our findings suggest that economic factors are major reasons for health workers migration. Lack of resources to maintain their family and social status were important push factors for Nepalese health workers as they experienced enormous differences in pay and living standards between the UK and Nepal. Many health workers from developing countries emigrate to improve living conditions; [13,25-26] many Nepalese people are migrating for economic opportunities to work in the Middle East.[27]

Security issues were also the key factors for Nepalese health workers who found themselves vulnerable in the work place, and they were prone to verbal and physical assaults due to a lack of law and order. The nurses felt more vulnerable than doctors did, but all were worried about the lack of legal protection of employees against the assaults. Most interviewees were frequently transferred to different parts of Nepal, including very remote ones and their individual circumstances were ignored. Especially, female nurses found that it was impossible to leave urban areas due to their responsibilities for children and families.

They found themselves helpless to accomplish their jobs effectively in remote areas due to lack of medications and logistic problems. Those working in the private sector experienced problems too, e.g. lack of incentives and deteriorating health care institutions. They were attracted towards other countries with better job security and higher satisfaction. Most felt that there were fewer skill development opportunities and an unfairness in its distribution in Nepal. Moreover, they were not happy with the traditional rigid hierarchical management system with its corrupt attitude towards the skilled workers.[9]

Power culture, favouritism, discrimination and prejudices on the different grounds were regarded as major barriers to their skill development. Whilst their eagerness to enhance their knowledge after post-basic training was hindered by a lack of advanced technology and specialists. Most considered up-to-date technology and trainings were very important and thought that they needed proper facilities for diagnosis and treatment including appropriate information technology and communication system. Those who worked in rural areas felt professionally deprived and could not achieve their potential in the job.

The majority of the interviewees felt not properly recognised for their skill and efforts; they rather felt neglected by those in authority. There were de-motivating factors in the health care system and lack of modern management techniques for the employee’s welfare, which ultimately pushed them to emigrate from Nepal. It is widely believed that most health care policies in developing countries are outdated and less effective in the changing global context; [28] as well as lack the long-term strategy to stop the out flow of health workers.[5]

Health workers experienced stress due to work overload as a result of hospital being understaffed. They felt helpless when patients died due to persistent shortage of medical supplies. In addition, they expressed the bitter reality that they had tools which were not working which led to the frustration, which they felt, was worse than the dissatisfaction.

The studies from Sub-Saharan African countries show that the health workers were obliged to move away from political unrest, ethnic violence, crimes and the threat of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and other diseases even though their basic needs were fulfilled in their own country.[29]

The respondents were not satisfied with the bureaucratic system in Nepal. Their concerns were decision making power, monitoring system, fair and justice in service provisions, better terms and conditions, work and life balance and equal opportunities would be the fundamental factors to be considered for the solution of the existing ‘desperation for moving abroad’ mentality.

However, most were happy with their UK earning and ability to maintain their personal and family life comfortably including the left behinds. Their dream to acquire further knowledge and skills seem to have fulfilled. Those struggling to settle were found to be frustrated and pessimistic about their future though they were enjoying universal health care services, education for children and social welfare system. Though, some were confused about the frequent changes in UK immigration rules; specially those who were unable to cope with government policies creating barriers to practise; as they were disconnected from their previous job and forced to go away with bare hands. Some interviewees experienced discrimination at work. All respondents were eager to share their skills with appropriate field in Nepal.

Peer group influence and family pressure have played pivotal role to decide to migrate in particular as there is long history of bilateral relationship between Nepal and the UK and the ‘Gurkhas’ in the British Army. Their textbooks, English literature and the education system influenced all the respondents, which is closer to the UK than others are. Some interviewees were jealous of the colleagues and peers who had worked in the UK and had a better family life and social standard in Nepal before they arrived to the UK. A study in West Africa also found strong peer group influence as people there have a long history of medical migration and they learned it from their professors, family and others about the tangible and intangible benefit from the migration.[30]

Strengths & weaknesses of the study

This study has explored some major obstacles for the retention of health workers in Nepalese context and it is the first study on this topic, which has opened the gateway for the future studies. The respondents were from diverse background; all of them had achieved medical degrees funded by the state; they had worked a minimum of five years in health care system in Nepal. All in-depth interviews were conducted, transcribed and analysed by the first author and the analysis was supported by the two co-authors, one of whom is a native Nepali speaker, improving internal validity. Interviews were in Nepali language and the respondents were active, enthusiastic and relaxed, therefore, this is a pioneering study for Nepal.

Limitations include the fact that there was not any authentic source of trend, pattern and magnitude of the health workers emigration from Nepal. Due to time and resource constraints, most interviews were conducted over the phone and other health workers apart from doctors and nurses were not included in this study.

Conclusion

This study identified major pull and push factors for the health workers’ migration from Nepal. Although, health workers migration is part of the increasing global trend of general migration, individual migrants appear to be moving countries to ‘better’ themselves and their families. Peer group influence was the major factor as migrants were ‘pulled’ by colleagues and ‘pushed’ by family to find a job in the UK.

Large and increasing social and economical disparities between countries also encouraged them migrate. Professional dissatisfaction related to the shortage of medical provisions and logistical problems in Nepalese health care establishments. Economic and security issues were central push factors, as well as the lack of opportunity to develop skills. The latter was influenced by a lack of technological advancement and experts to train health professionals. Interviewees also raised issues of favouritism, discrimination, corruption and a lack of proper (health) management skills in the system. The political unrest in Nepal and its hierarchical culture also led to dissatisfaction with the existing system in Nepal.

There will always be health worker emigration if government policies cannot address their individual, family and societal problems. Having proper management systems and technology to maintain their living standards are equally important considerations.

Finally, health workers emigration means a loss of skilled human capital (‘brain drain’). However, there are some positive outcome for the sending country in terms of remittance and skill transfer. Socio-economic disparities, internal security, inequalities, social segregation and political instability in the developing countries may help increase ‘one-way’ traffic to developed countries. Health worker migration is a global problem, which needs global solutions, especially the need for international organisations and governments to manage migration in this era of interdependency and globalisation.

Finally, there is a need for large-scale quantitative studies into health workers problems in Nepal including professionals other than nurses and doctors. There is an urgent need to determine the number of health workers emigrating including pattern, magnitude and trend to address the recruitment and retention problems.

Tables at a glance

2774

References

- Michael M, Black R, Mills A. International Public Health: Diseases, Programs, Systems and Policies. 2nd edn, Sudbury: Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2006.

- Pang T, Lansang MA, Haines AA. Brain Drain and Health Professionals: A Global Problem Needs Global Solutions. Brit Med J, 2002; 324(7336): 499-500.

- Afzal S, Masroor I, Shafqat G. Migration of Health Workers: A Challenge for Health Care System. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak, 2012; 22 (9): 586-587.

- McDonald JT, Worswick C. The migration decisions of physicians in Canada: the roles of immigrant status and spousal characteristics. SocSci Med, 2012; 75(9): 1581-88.

- Stilwell B, Diallo K, Zurn P, Dal Poz MR, Adams O, Buchan J. Developing evidence based ethical policies on the migration of health workers: conceptual and practical challenges. Hum Resource Health. 2003; 1: 8; doi:10.1186/1478-4491-1-8.

- Buchan J. Health worker migration in Europe: Policy issues & options. HSLP Institute, London, 2007. Available: www.hlsp.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=SM55vQDY0bA%3D&tabid=1702&mid=3361

- Johnson J. Stopping Africa's medical brain drain. Brit Med J. 2005; 331 (7507): 2-3;

- Viel B. Migration of medical manpower: general observation. The Josiah Macy, jr foundation., New York, 1979; 157-161

- Lucas A. Human Resources for health in Africa. Brit Med J. 2005; 331: 1037-38;

- Adkoli V. Migration of Health Workers: Perspectives from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, 2005. Available : www.searo.who.int/LinkFiles/Regional//

- Connell J. International migration of health workers. Routledge.; New York, 2008; 10-30

- Lokshin M, Bontch-Osmolovski M, Glinskaya E. Work Related Migration and Poverty Reduction in Nepal. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. 4231, 2007. Available : https://elibrary.worldbank.org/content/workingpaper/10.1596/1813-9450-4231

- ILO. Migration of health workers: Country case study Philippines. International Labour Organization. Geneva, 2006.

- Lowell B. Skilled Migration Abroad or Human Capital Flight? Institute for the Study of International Migration. Georgetown University, 2003. Available from: www.migrationinformation.org/

- Brown L, Holloway I. The adjustment journey of international postgraduate students at an English university: An ethnographic study. J Res IntEduc, 2008; 7(2) 232?249.

- Mensab K. Responding to the Challenge of Migration of Health Workers: Rights, Obligations, and Equity in North/South Relations. Global Soc Pol, 2008; 8(1): 9-11.

- Seddon D, Adhikari J, Gurung G. The New Lahures: Foreign Employment and Remittance Economy in Nepal. Nepal Institute of Development Studies, Kathmandu, 2001.

- Bhattarai R. Open borders, closed citizenships: Nepali labour migrants in Delhi International migration, multi-local livelihoods and human security. Institute of Social Studies, The Hague, the Netherlands, 2005. Available from: www.iss.nl/content/download/8271/80771/file/Panel5

- Kollmair M, Manandhar S, Subedi B, Thieme S. New figures for old stories: migration and remittances in Nepal. Migration Lett, 2006; 3(2):151-160.

- Adhikari J, Bhadra C, Gurung G, Niroula B, Seddon D. Nepali Women and Foreign Labour Migration. Kathmandu: UNIFEM/NIDS, 2006.

- DFID. Annual Report Nepal, 2005 [Online available: https://www.dfid.gov.uk/]

- Adhikary PP, Simkhada PP, van Teijlingen E, Raja AE. Health and Lifestyle of Nepalese Migrants in the UK. BMC Int Health Human Rights, 2008; 8: 6.

- Bowling A. Research Methods in Health: Investigating Health & Health Services. 2nd edn., Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2002: p. 352-354

- vanTeijlingen E, Hundley V. The Importance of Pilot Studies. Social Research update, issue 35; University of Surrey, 2001.

- Mullan F. Doctors for the World: Indian Physician Emigration. Health Affairs, 2006; 25(2): 380-92.

- Record R, Mohiddin A. An economic perspective on Malawi's medical "brain drain". Globalization Health, 2006; 2:12. Available: www.globalizationandhealth.com/content/2/1/12

- Adhikary PP, Keen S, van Teijlingen E. Health Issues among Nepalese migrant workers in the Middle East. Health Sci J, 2011; 5 (3):169-175.

- Bloom G, Han L, Li X. How Health Workers Earn a Living in China. Hum ResourDev J, 2001; 5 (1?3): 25?38.

- Awases M, Gbary A, Nyoni J, Chatora R. Migration of health professionals in six countries: A synthesis Report, Brazzaville: WHO Regional Office for Africa, 2004. Available from: https://info.worldbank.org/etools/docs/library/206860/Migration%20study%20AFRO.pdf

- Hagopian A, Ofosu A, Fatusi A, Biritwum R, Essel A, Gary Hart L, et al. The flight of physicians from West Africa: Views of African Physicians and implications for policy. SocSci Med, 2005; 61(8): 1750-60.