Keywords

Sickle cell disease; Transition; Patient; Adolescent; Health services; Care standards

Introduction

Healthcare transition is defined as “ a multifaceted, active process that attends to the medical, psychosocial, and educational/vocational needs of adolescents as they move from the child-focused to the adult-focused health-care system” [1]. However, despite the presence of national guidelines and local recommendations relating to good transitional care, there is evidence of broad variability in practice [2,3] and inequitable delivery and access to care. These inconsistencies present an additional challenge for patients and their families during a complex period of physical, psychological and social change [3,4]. As such, a well-managed transition is likely to equate to greater engagement in care and improved health outcomes. In contrast, a poorly managed or poorly implemented transition is associated with interruption in care, non-adherence to treatment, increased hospitalisations and poorer health outcomes [3,4].

While the process of transition can be applied to all chronic conditions that start in childhood and continue into adult life, this paper will explore the current situation for sickle cell disease (SCD) and propose recommendations that could form the basis of a national framework in this highly specialised and complex field. Over the past 30 years, outcomes for people living with SCD have been transformed through advances in health and medical care, with almost all those born with SCD in highincome countries surviving long into adulthood [3,5]. For example, it is estimated there are currently between 12,500 and 15,000 people with SCD in England [5] with an estimated median survival of SCD patients from one tertiary UK hospital of 67 years [6].

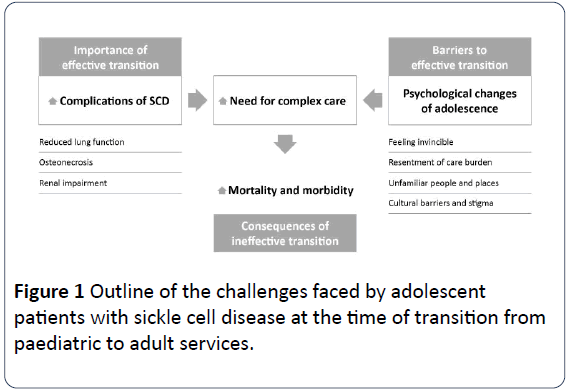

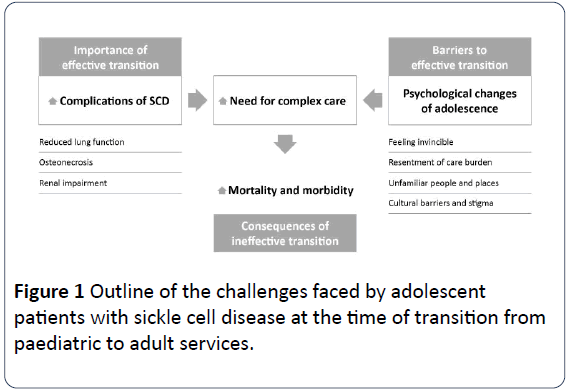

Adolescence can be a particularly demanding time for patients with SCD. It is during this period that some of the longterm complications of the condition may begin to manifest and give rise to signs and symptoms. As well as impairing quality of life, this increases the likelihood they will need access to increasingly complex healthcare services [3] and comes at a time when patients are facing the usual psychological and social challenges of adolescence. This convergence of critical factors highlighted in Figure 1 also occurs when the care of young people with SCD is in the process of transition from paediatric to adult teams and facilities [3,7].

Figure 1: Outline of the challenges faced by adolescent patients with sickle cell disease at the time of transition from paediatric to adult services.

Historically, SCD patients received treatment in large sickle cell centres based in major UK cities. Now, however, patients are more frequently managed in areas of the country where the transition process from child to adult care may be less effective or even non-existent. With the vast majority of children living with SCD (more than 95%) surviving into adulthood, their successful transition into adult care is considered a critical part of the process [8]. Therefore, clear potential exists to develop a person-centred national framework that can be applied at a local level to bolster the understanding, skills and confidence of young SCD patients at this critical juncture in their lives and facilitate their journey through paediatrics to adult care in a safe and individualised way.

In view of these challenges, an expert panel was formed to: (i) identify the barriers and facilitators to optimal transition; (ii) to propose consensus recommendations and future considerations to advance the transitional care of adolescents with SCD in the UK.

Method

In May 2018, a multidisciplinary expert panel of UK healthcare professionals, patient advocacy organisations and patient representatives met for an all-day consensus meeting and workshops to scope a framework that would enable HCPs at a local level to better enable and prepare young SCD patients for their transition process from paediatric into adult care. The objective of the meeting and workshop was to understand and characterise the key aspects of the patient journey for young people with SCD, the barriers and facilitators experienced at each stage and propose recommendations to overcome them.

The expert panel comprised two consultant haematologists, three clinical nurse specialists and one consultant psychologist, as well as representatives from the Sickle Cell Society and Roald Dahl ’ s Marvellous Children ’ s Charity. In addition, the panel heard from two patients with SCD and one parent, who were invited for part of the meeting to share their thoughts and experiences of the transition process.

Prior to the meeting, two online polls were sent to panel members and patients/ patient group representatives, to draw out their experience of transition from child to adult care.

The consensus meeting was conducted as follows: (i) Short introductory presentation on the impact of transition from paediatric to adult care; (ii) Transition case studies and current practice presented by panel members; (iii) Patient and parent experiences. This session took the shape of an interview-style conversation where the meeting facilitator (from the supporting medical communications company) asked a series of questions about their experiences of the transition process and what, from their perspective, could be improved. Towards the end of the session, the panel members were given the opportunity to ask additional questions; (iv) Roundtable discussion of findings from the two small online polls and to define the crucial touch points in the patient journey; (v) The expert panel were separated into two groups to identify potential barriers and facilitators to effective transition, and where each barrier or facilitator was most likely to impact along a notional age/development timeline. Each factor was subsequently assigned a priority ranking (1 being the least important and 5 being the most important) to represent the critical touch points in a successful journey for a patient with SCD; (vi) The panel reconvened to present, discuss and refine these barriers and facilitators; (vii) The recommendations to shape the consensus statement were discussed.

Given the paucity of consensus guidance in this area, the panel felt it would be beneficial to the sickle cell community to establish a set of key recommendations and practical approach that would enable paediatricians, haematologists, sickle cell specialists, clinicians, and other healthcare professionals across the UK, to implement an optimal process relevant to their own practice and patients.

All discussions were facilitated by a moderator from the medical communications company, audio recorded, and the outputs consolidated into a draft paper, which was then circulated and commented on until a draft acceptable for submission was developed.

The resulting consensus agreement therefore reflects the combined experience of the attending healthcare professionals and advocacy groups, based on practical and clinical expertise, and informed by patient/parent insight and experience. While developing the consensus agreement for publication, additional UK haematology experts were approached by the sponsoring company to review the synopsis and so further consolidate the focus and recommendations outlined.

Results

In considering the current situation relating to the transition of care from paediatrics to adult services for young people with SCD, the expert panel explored several key points. Many young people are unprepared for the adult environment, which they may first encounter during an acute painful episode. In the absence of a structured transition process, young people presenting with an acute vaso-occlusive episode in the emergency department of an acute hospital, may find themselves being managed by an unfamiliar adult clinical team due to strict age restrictions governing treatment policies in many units.

Here, they may lack the skills and confidence needed to adequately explain their health condition and receive timely and adequate treatment. Additionally, the absence of advocacy by a named transition healthcare professional may result in a lack of understanding among providers of the complex and multifaceted needs of a young person with SCD. This misunderstanding of SCD, crises and pain behavior by healthcare providers, particularly in the acute and emergency settings, can provoke negative experiences of adult care and provide an additional barrier to successful transition. These findings are in line with the results of the UK healthcare professional online poll summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Summary of findings from a small online poll with UK healthcare professionals.

| Topic areas |

Themes from UK healthcare professionals (n=6) |

| Benefits of a seamless transition |

Familiarity with new team and processes, expectations managed |

| Improved trust, know how to get help, confidence in our service |

| Confidence for the future, better self-management, autonomy |

| Fewer interruptions to school/college/university/work |

| Less unplanned admissions, less acute morbidity |

| No interruptions to prescribed treatments, treatment adherence |

| Social and peer support, educational achievement, employment |

| Consequences of an unplanned transition |

Fear of unknown, feeling of being abandoned by familiar team |

| Lack of trust, communication difficulties, treatment and adherence issues |

| Lack of healthcare input, lost to follow up, poor health outcomes |

| Interruptions to education/work |

| Poor outcomes, illness behaviour impacting physical, mental health |

| Poor social outcomes |

| Optimal age to start transition |

Responses ranged between age 10 and 15, dependent on maturity |

| Ideal change to current transition process |

Involving the wider hospital in understanding what it is like to move from children to adult services |

| Improve the adolescent in-patient environment |

| Additional resources |

| Most challenging aspects for patients |

Losing the familiarity of the children setting and making new relationships |

| Learning to trust new team, fearing admission, understanding how new systems work |

| Knowing who to contact, being admitted to adult wards with much older patients |

| The wider hospital recognising the needs of this group |

| Lack of support |

| Most challenging aspects for HCPs |

Ensuring patients engage fully with the process |

| Involving the wider hospital |

| Lack of resources |

| Set age of actual transfer from paediatric care to adult care |

From the patient and parent’s perspective, there are similar challenges. The care received in the adult service may be in an unfamiliar location or environment and there may be minimal information relating to the process, timeframes or expectations of transition. For the patients and parent attending the consensus meeting, there was a lack of clarity relating to their transition and the move to adult care felt “too sudden” (Table 2).

Table 2: Summary of findings from patients attending the consensus meeting.

| Topic areas |

Themes from patients (n=2) |

| Challenges faced by patients |

Care received in the adult setting was in a different hospital and different area |

| Lack of information on the differences between paediatric and adult care or what to expect |

| Told they would transition, but not given a timeline. Transition happened because of the circumstances |

| Stayed in mixed sex adult wards, with elderly patients and those with mental health issues |

| Did not know they had to ask for pain relief, food or drink, which would have been offered automatically in a paediatric ward |

| Didn’t feel confident enough to speak about their feelings |

| The need to take responsibility felt a lot to deal with while in pain |

| Asked several questions, felt stigmatised and that HCPs on the adult ward lacked understanding, particularly regarding pain and pain relief |

| How to improve transition |

Transition should not be purely clinical, include personal development, education, confidence building, role play scenarios, peers, expert patient mentors. All aspects of life should be considered and integrated in the transition plan |

| Employ visual, online channels to deliver information to patients, e.g. YouTube. Develop materials from the patients’ perspective |

| Having a date to work towards, i.e. a deadline to completely transition into adult care |

| Being shown the adult wards before being admitted, setting expectations to ensure emotional preparedness |

| A visual experience of the entire process on what to expect from the adult hospital before the transition, e.g. seeing A&E, the ward, the pharmacy, the X-ray department, the canteen, etc. |

Lack of confidence in self-advocacy was of concern to the patients at the meeting, as was worry about the degree of autonomy and self-management required during treatment episodes within adult services. Although the majority (66%) of the small online poll among patients (n=6) said their experience of transition had been “okay”, the remaining 33% defined their transition as either “easy” or “very easy”. Despite this, there were clear indicators for improvement in the poll, including the provision of more information (17%), having access to a psychologist (17%), starting transition later (33%), having a nurse lead (33%), and the opportunity to meet the adult team prior to transition (83%).

Quote: “At the transition stage, I was never very far [from home]. I wasn’t comfortable. I wasn’t in a good place. It was a lot for me to deal with. Now…I feel safe to go anywhere. That’s because of the things I have in place.” Patient living with SCD.

Barriers and facilitators to transition

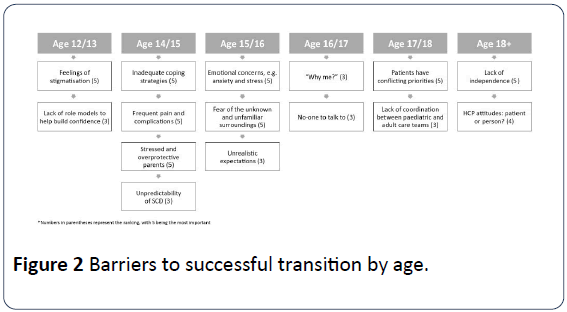

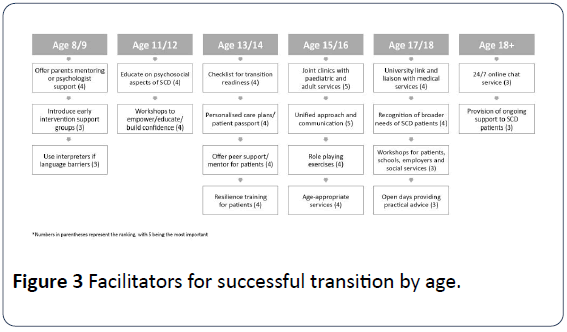

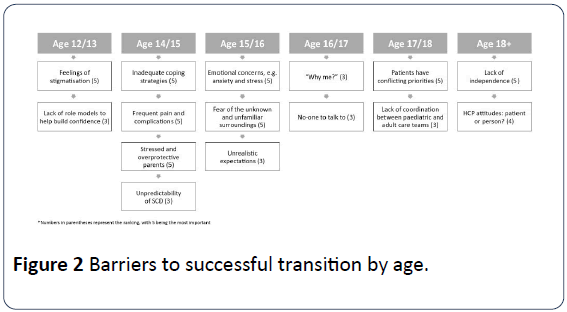

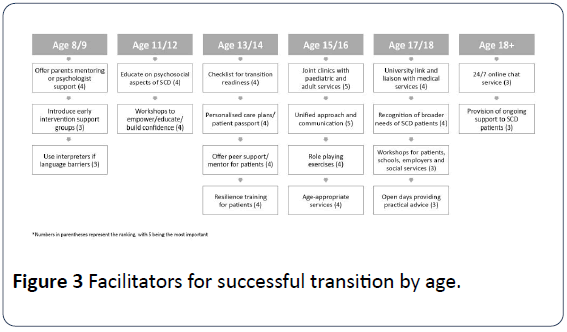

As part of the process, the expert panel identified more than 50 barriers and facilitators to a successful transition in young people with SCD from 8 through to 25 years. These are summarised in Tables 3, 4, Figures 2 and 3.

Table 3: Key barriers to transition: the whole patient journey.

| 1 |

Fear of being different; potential stigma in some cultures and related to requirements for pain relief in the adult setting; cultural barriers primarily affecting parents |

| 2 |

Lack of reliable information available to patients and parents regarding this condition |

| 3 |

Lack of understanding and knowledge of the condition by wider healthcare professionals, particularly in the emergency setting. Poor understanding and knowledge of transition/adolescent needs by HCPs in the wider hospital and health community |

| 4 |

Lack of adequate preparation while in paediatrics and sudden transition into adult services |

| 5 |

Lack of non-health-related input, such as social support |

| 6 |

Patients’ lack of confidence/ability to adjust to an adult care setting; feelings of abandonment by paediatric team and unfamiliar/uninviting adult environment |

| 7 |

Lack of approach to empowering and supporting patients from an early age; adequate information and signposting for adult care services, e.g. how to make an appointment with the GP |

| 8 |

Lack of age-appropriate patient information, materials and signposting; lack of reliable age-appropriate digital media channels, e.g. YouTube videos |

| 9 |

Institutional barriers |

| 10 |

Lack of psychologists with an interest and experience in SCD across the NHS; many trusts have limited access to health and neuropsychologists |

Table 4: Key facilitators to transition: the whole patient journey.

| 1 |

Established timelines for transition shared and agreed between patients, parents and HCPs |

| 2 |

Use of SCD transition guidelines where available |

| 3 |

Patient access to a designated transition healthcare professional and psychologist; ensure clinic accessibility for patients and strategies to engage |

| 4 |

Psychological preparedness and expectation setting for adult care |

| 5 |

Social and psychological support groups for patients and their families, e.g. workshops, role play scenarios, confidence-building exercises, open evenings and peer support programmes and sessions with recently transitioned young people who can be role models/mentors. |

| 6 |

Adolescents and young people with SCD would benefit from a hands-on experience of the entire process before transition, i.e. what to expect from adult care services, including a tour of adult services, meeting the adult care team |

| 7 |

Structured education for HCPs within the broader hospital, in particular A&E and the emergency teams, and community settings on caring for adolescents and the importance of an effective transition process in SCD, including the psychosocial aspects |

| 8 |

Patient materials presented from the patient perspective in an age-appropriate and visual format, e.g. YouTube |

| 9 |

Ensuring the transition process encompasses personal development, education and confidence building, in addition to the medical aspects |

| 10 |

A holistic approach to the transition process needs to be adopted. Every aspect of the patient’s life should be considered and integrated into the transition process. |

Figure 2: Barriers to successful transition by age.

Figure 3: Facilitators for successful transition by age.

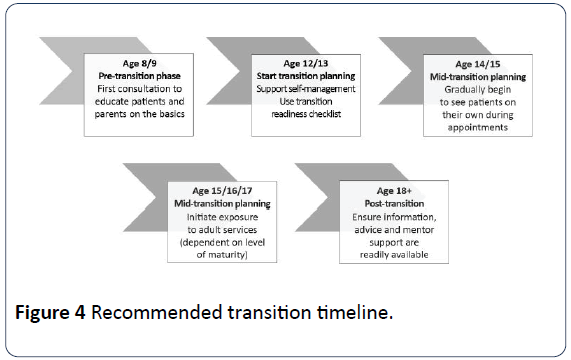

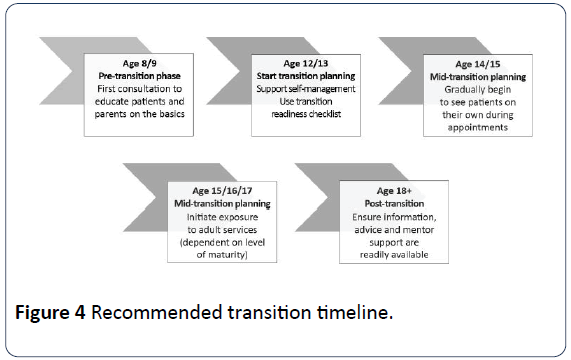

The panel observed several critical stages throughout the patient journey, including a pre-transition period to introduce the concept through family-oriented discussions and gradually leading to one-to-one consultations with the child, to encourage greater awareness and confidence about their condition and its complications (Figure 4). This educational aspect for parents and children should start early in life and by age 8ËÂâ€â€Â9 where possible. However, transition should not be discussed at this stage.

Figure 4: Recommended transition timeline.

Instead, transition planning should start age 12ËÂâ€â€Â13 with a readiness checklist [9] to assess gaps in patients’ knowledge and address fears or concerns about the transition process. This readiness assessment would also help ensure transition support is developmentally appropriate and aligns with each patient’s maturity, cognitive abilities and psychological status (Appendix 1).

Furthermore, the panel recommended each young person have a named transition healthcare professional and an individualised transition plan to empower both parents/carers and patient with the skills required to facilitate better transition into the adult care setting and optimise their personal health outcomes. Strengthening the opportunities for two-way communication between the paediatric and adult services was also reinforced, with the understanding that if any of the steps outlined in Figure 2 are missed at an earlier age, these should be assessed/take place later in the process.

Active engagement of parents and carers in the transition process may be as important as engaging the young person themselves. Family can play a critically supportive role by promoting health maintenance and wellbeing from birth, establishing the foundations for future self-management, as well as dealing with acute and longer-term effects of the disease process (Appendix 2). The scope of this is evidenced in the transition care guide developed by Central Manchester University Hospitals, UK, and discussed at the consensus meeting, which includes 57 different goals that follow the child from birth through to age 20 and include numerous objectives that focus specifically on the role of parents (Appendix 2).

As the booklet on SCD in children developed by the Joint Red Cell Unit at the University College London Hospital states, “As your child gets older, we will expect them to take more responsibility for their health” [10]. In this way, parents need not only to prepare their children to take ownership of their health, but must also prepare themselves to step back at the appropriate time and encourage older adolescents to build their own relationships with the care team.

More broadly, it was also felt that this heightened focus on providing comprehensive transition programmes and provision of a mandatory lead may also see the future creation of a strategic role covering transition service development within NHS organisations. Advocating for representation at a strategic level where both transition and funding issues can be championed is likely to make it easier to develop a unified transition protocol that acts as an umbrella for all paediatric to adult chronic conditions and can be embedded within a health service framework.

This publication does not intend to define every step of the process, but to propose a framework for transition, including consensus recommendations which were agreed by the panel following extensive discussion. The practical nature of these recommendations, outlined below, should enable them to be tailored to individual patient needs, as well as those of the local hospital and healthcare community.

Consensus recommendations

To ensure successful delivery of the patient from paediatric into adult care will require key principles and pathways to be established:

• The process of transition should start in early adolescence, but education about their condition and self-management should begin much earlier (pre-transition phase), where possible.

• A named transition healthcare professional within a multidisciplinary team should be appointed who will take responsibility for the individual’s transition.

• Each patient should have an individualised transition plan and should include a formal referral process from paediatrics to adult services if required.

• HCPs should prepare young people for the practical and operational differences between paediatrics and adult care settings in the hospital and the community. There should be efforts made by paediatric and adult services to provide representation for each other’s clinics or, ideally, host joint clinics.

• HCPs should aim to establish peer-support programmes and weave them into the transition model.

• Successful transition will require close collaboration between the hospital, community services, general practice, schools and further education, as well as other health and social care providers. There should be a HCP as a point of contact at the adult services to encourage young people to engage with the new team and attend appointments.

• Communication is crucial and may include multidisciplinary meetings and/or patient-held shared care records, with a named key contact for advice [5]. Either a hand-held patient passport, phone-held record or app would enable individuals and HCPs to know where they are in the transition process, though validation of such tools may be required within the context of the UK.

• Support should be offered to HCPs within the broader hospital environment and wider health community to recognise that young people have different needs compared to adult patients. Establishing connections with other hospitals could be considered, particularly in low prevalence areas and where transition protocols may have been developed in other therapy areas (e.g. diabetes).

• Ideally, there should be a national initiative to develop validated transition readiness and assessment tools that can be used as a benchmark to assess the gaps and to measure the outcomes, examples of which include the Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) [11,12] and the transitional care guide Based on patients’ responses, HCPs can equip and empower young people and their parents to better understand their disease and build confidence to express their needs. The process should be streamlined between paediatric and adult services, supported by the provision of local guidelines where applicable and a checklist to ensure the required stages have been completed. Measures should be put in place to ensure such validated tools are routinely implemented and any steps missed at an earlier age are addressed.

• Healthcare professionals should ensure that educational institutions are equipped with a healthcare plan to support students with SCD in their education, their health and future employment. In addition, further education institutes, such as universities and colleges, should also bear responsibility for developing and monitor strategies to support students with SCD [5].

Discussion

The importance of a positive transition process for an SCD patient’s understanding and self-management of their condition is recognised as being central to improving outcomes associated with their long-term care. Conversely, if young people are not supported through a planned transition it can result in a negative impact on their physical, emotional and social care needs [2]. Furthermore, without appropriate support to manage the transition process, there is evidence of disengagement with services and poorer health outcomes [4].

However, while there are recognised recommendations for healthcare systems to develop structured transition plans for all patients moving from child to adult services [4] there is little specificity regarding the shape of such programmes and a lack of evidence relating to outcomes [5,13].

Consequently, recent data from patient-reported surveys serve to highlight the poor encounters of care experienced by adolescents with SCD [14] which may be compounded by feeling unable to express their needs or adequately explain their health condition [15]. Patients should, therefore, be helped to adjust to the adult care environment and equipped with strategies that enable them to deal with these challenging situations [13].

Considering this, the panel proposed a series of consensus recommendations for transition, specific to SCD but leaning on knowledge of existing frameworks in other chronic conditions, including diabetes and cystic fibrosis. These are shown in the preceding section and discussed further below.

Critical elements for successful transition

There is broad consensus that this early implementation of the transition process is essential for successful transfer to adult services [8].

This process may require the inclusion of various professionals crossing health, social and educational care, to mitigate additional challenges for the young person during this critical time. Therefore, appointing a healthcare professional to coordinate and support the young person and their family/carer before, during and after transition may result in an improved experience, increased attendance in adult services and better overall outcomes [2].

While no one transition model has been universally adopted, there are broad similarities with those most frequently implemented, including the Ready, Steady, Go framework created by the University of Southampton, and the ‘patient passport’ model employed by Guy’s and St Thomas’ (Appendix 3). Although it is important to align nationally, each protocol should be adapted to suit local circumstances.

Emphasis should also be placed on strengthening shared working practices and two-way communication between the children ’ s and adult services to ensure the transition recommendations are cohesive, routinely implemented and underpinned by a well-thought-through engagement strategy. As medical complications requiring emergency care are likely to fall to adult teams during transition, improving knowledge among non-specialist HCPs and alerting them of SCD patients’ complex acute needs is also recommended.

It is critical, therefore, to also consider the time points at which transition into adult services takes place as the process can be quickly interrupted, resulting in additional challenges to the provision of care and support [4]. Similarly, weight must be given to the structure, frequency and practical accessibility of any transition programme, moving from the paternalistic approach toward engaging young people in this process, even when they are well, to lay the foundations for a positive experience of their move into adult services.

Measuring outcomes

Evaluating the outcomes in terms of practical execution of the transition model is complex, although models exist for other chronic conditions that can be applied and assessed in the context of sickle cell [16,17].

Outcomes may be measured both qualitatively and quantitatively (Table 5), but emphasis should be given to the creation of validated qualitative tools that offer the opportunity for more meaningful results pertaining to patient experience and quality of life pre- and post-transition.

Table 5: Measures of pre and post transitions.

| Quantitative measures pre and post-transition |

Qualitative measures pre and post-transition |

| Rates of hospitalisation |

Transition readiness checklists, before, during and after formal transfer of care |

| Patient reported experience measures, e.g. Experience of transition Illness perception |

| Assessment of coping skills |

| Length of hospital stay |

Knowledge base |

| Uptake of scheme by young people/families |

| Quality of life measures |

| e.g. EQ-5D-can be used from pre-transition phase |

| Mortality |

Health utility index-QALY |

| Patient satisfaction surveys and rating scales |

| Unplanned admissions |

How smooth was this process? |

| How do you feel now you are in adult care? |

| Do not attend rates in clinic |

Patient journal, including pain tracker |

| Traffic light system for mild, moderate or severe pain to aid recall |

This qualitative approach would also reveal information relating to the issues and challenges of the transition process at the individual hospital level from the patient perspective, analysed in a clear and scientific way to determine the impact of intervention. However, more research is required to identify these optimal processes and develop an evidence base to promote best practice.

This qualitative approach would also reveal information relating to the issues and challenges of the transition process at the individual hospital level from the patient perspective, analysed in a clear and scientific way to determine the impact of intervention. However, more research is required to identify these optimal processes and develop an evidence base to promote best practice.

Our recommendations reflect that, rather than being a purely clinical process, transition should be multifaceted and active. It should ensure young people and their families or carers feel enabled to make the move from paediatric into adult care and for this to be a positive experience.

Rather than working in isolation, there should be a strategic vision for an NHS or hospital-wide programme regarding the transition process, as the onus shifts from the paediatric teams to careful coordination of care and responsibility among multidisciplinary HCPs who provide the network of support for people living with SCD [18].

This must ensure that ongoing initiatives, in well-established transition programmes, are adopted or adapted to offer consolidated guidelines for transition protocols that can be localised and specified according to the condition. Furthermore, the appointment of an individual able to operate at a strategic level within transition services across all relevant chronic conditions should be considered. In this context, it is important to identify how these services might be developed and appraised, as well as the skills and training required to enable healthcare professionals to take on these specialist roles.

Conclusion

People living with SCD are now anticipated to live a near normal lifespan. However, with this comes a complex array of challenges for resource-constrained healthcare systems, with the focus shifting from the clinical management of acute complications towards a holistic, person-centred future that looks to meet a broad spectrum of patient needs.

An additional challenge arises in people with chronic conditions such as SCD where their move into adult services coincides with the many other emotional, social, developmental and physical transitions representative of adolescence. Furthermore, there is greater likelihood of disease complications during this timeframe, a higher frequency of hospital admissions and need for more complex care arrangements [3,15].

These additional complications and challenges give rise to the necessity for early involvement of the patient and their families in the transition process, to create a level of confidence and empowerment to manage their health and SCD in an optimal way.

Involving young people in decisions about their health, treatment and transition planning, is outlined in existing recommendations [2]. However, evidence suggests that earlier guidance is not always being implemented, leading to variable provision and lack of standardisation throughout the country [19]. Consolidating the existing care networks to support transition in SCD wherever they are in the UK, would ensure patients living with SCD have equality in access to care and treatment wherever they live in the UK.

These consensus recommendations and transition protocol should be shared among services and HCPs wherever possible to ensure other specialty teams within the hospital and community settings are made aware of the process. While there is little evidence or clarity in how best determine the success of an individual’s transition, this paper aims to provide a starting point for the creation of universally deployed metrics and measures for HCPs wishing to adopt the guidelines. In this rapidly evolving field, the recent publication of a pilot study to trial a validated patient experience measurement tool on transition provides useful insights into the determinants of success [20].

As part of this, those HCPs and centers wishing to adopt these recommendations should consider setting a baseline and establishing metrics by which to measure success.

In conclusion, this consensus document builds on earlier general standard of care to set out a plan of action for optimal provision of transitional support and services for young people moving into the adult care setting, and to enable the translation of national standards into established local practice. The future of adolescent medicine, and specifically transition, will require collective thinking to provide the strategic oversight, investment in people, resources and services to deliver expert and optimal care in SCD.

Acknowledgements

Chris Toller, Havas Life Medicom, chaired the consensus meeting that was held at the Novotel London Paddington, London, UK, in May 2018.

The consensus group

Subarna Chakravorty, Kofi Anie, Sophie Dziwinski*, Banu Kaya, Elizabeth Green, Siann Millanaise, Luhanga Musumadi, Katherine Stevenson. *Sophie Dziwinski replaced Jane Miles as representative of the Roald Dahl Marvellous Children’s Charity following the latter ’ s retirement as Chief Executive of the charity.

Medical writing support was provided by Ada Ho and Claire Rodger at Havas Life Medicom, supported by Novartis. All drafts of the paper were reviewed and discussed by the consensus group prior to submission.

Disclosures

The online poll and consensus meeting were arranged and facilitated by Havas Life Medicom and funded by Novartis.

All authors or their corresponding organisations received a fee from Novartis for participation in the consensus meeting and contributed equally to the development of the paper. However, this manuscript in no way discusses or sponsors specific treatments or interventions.

Novartis reviewed the final consensus paper for factual accuracy but responsibility for opinions, conclusions and interpretation of clinical evidence, and the submitted draft, lies with the authors.

Declaration of Interests and Funding

All authors or their corresponding organisations received personal fees from Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK for participation in the consensus meeting in May 2018. In addition, Subarna Chakravorty has received personal fees from Novartis outside of the submitted work. Kofi Anie has undertaken research sponsored by grants from Novartis outside the submitted work. Banu Kaya has received sponsorship from Novartis to cover registration fees and travel expenses for conference attendance and has also received sponsorship from AstraZeneca to be part of a steering committee for a clinical trial. Siann Millanaise reports grants from Blue Bird Bio and Terumo BCT. All other authors Sophie Dziwinski, Elizabeth Green, Luhanga Musumadi and Katherine Stevenson report no relevant conflicts of interest outside of the submitted work.

24486

References

- Blum RW, Garell D, Hodgman CH (1993) Transition from childÃÂÃÂÃÂâÂÂÃÂâÂÂÃÂâÃÂÃÂââ¬Ã

¡ÃÂâââ¬Ã

¡ÃÂìÃÂÃÂââ¬Ã

¡ÃÂâÂÂÃÂÃÂcentered to adult healthÃÂÃÂÃÂâÂÂÃÂâÂÂÃÂâÃÂÃÂââ¬Ã

¡ÃÂâââ¬Ã

¡ÃÂìÃÂÃÂââ¬Ã

¡ÃÂâÂÂÃÂàcare systems for adolescents with chronic condition. A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health 14: 570-576.

- Montalembert M, Guitton C (2014) Transition from paediatric to adult care for patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol 164: 630-635.

- Sickle Cell Society (2018) Standards for the Clinical Care of adults with Sickle Cell Disease in the UK.

- Gardner K, Douiri A, Drasar E (2016) Survival in adults with sickle cell disease in a high-income setting. Blood 128: 1436-1438.

- Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR (2010) Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood 115: 3447-3452.

- Sivaguru H, Kemp SM, Crowley R (2015) G409(P) An evaluation of the transition to adult care for young patients with sickle cell disease. Arch Dis Child 100: A168-A169.

- Howard J, Woodhead T, Musumadi L, Martell A, Inusa BP (2010) Moving young people with sickle cell disease from paediatric to adult services. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 71: 310-314.

- University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Joint Red Cell Unit. Sickle Cell Disease in Children. 2015.

- Wood DL, Sawicki GS, Miller MD (2014) The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ): its factor structure, reliability, and validity. Acad Pediatr 14: 415-422.

- Brown L, Sobota A (2016) Measuring transition readiness of young adults with sickle cell disease using the transition readiness assessment questionnaire. Blood 128: 3534.

- Bemrich-Stolz C, Halanych J, Howard T, Hilliard L, Lebensburger J (2015) Exploring adult care experiences and barriers to transition in adult patients with wickle cell disease. Int JHematol Ther 1: 1-5.

- Chakravorty S, Tallett A, Witwicki C (2018) Patient-reported experience measure in sickle cell disease. Arch Dis Child 103: 1104-1109.

- Lebensburger JD, Bemrich-Stolz CJ, Howard TH (2012) Barriers in transition from pediatrics to adult medicine in sickle cell anemia. J Blood Med 3: 105-112.

- Van Walleghem N, Macdonald CA, Dean HJ (2008) Evaluation of a systems navigator model for transition from pediatric to adult care for young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 31: 1529-1530.

- Johnson VL, Simon P, Mun EY (2014) A peer-led high school transition program increases graduation rates among Latino males. J Educ Res 107: 186-196.

- White PH, Cooley WC (2018) Transitions Clinical Report Authoring Group, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians. Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics 142: e20182587.

- West Midlands Quality Review Service (2016) Services for people with haemoglobin disorders: Peer review programmes 2014-16 overview report, Version 2.

- Witwicki C, Hay H, Tallett A (2015) Piloting a new Patient Reported Experience Measure for Sickle Cell Disease: A report of the findings. Picker Institute Europe, pp: 1-55.