Keywords

myocardial infarction, sexual counseling, nursing

Introduction

More than 7.5 million in the United States alone have experienced a myocardial infarction (MI) (American Heart Association, 2002). Recovery from an MI includes adapting to physical changes and invokes psychosocial responses such as anxiety and depression. Patients are anxious to resume their usual activities after an MI, including sexual activity. However, they may be afraid that engaging in sexual activity could lead to further myocardial damage or even death. An individual may also be concerned about decreased sexual performance following the MI. Furthermore, some prescribed medications do have sexual side effects, further increasing the patient’s anxiety in this respect (Steinke & Swan, 2004).

Because such a major life event, both for patients and their families, as MI often demands modification of lifestyle following discharge from hospital (Briggs, 1994), patients naturally receive education relating to medications, diet, exercise, when to return to work, when to resume driving their car and how to deal with or modify stress in their lives (Crumlish, 2003). However, the resumption of sexual activity post-MI is one area that is frequently neglected, despite being of great concern to the patient and his or her partner (Albarran & Bridger, 1997). Sexual counseling is an area of nursing practice that is often overlooked (Steinke & Patterson-Midgley, 1996). While exchange of information concerning sexuality post-MI is accepted as an essential part of the nurse’s role (Steinke, 2000; Katz, 2003), the evidence suggests that nurses are not assessing each patient’s needs nor are they giving health advice about sexual concerns (Gamel et al, 1993; Albarran & Bridger, 1997; Albarran, 2000). Many nurses feel disinclined to provide sexual counseling because they have not had the educational preparation and thus lack confidence in dealing with these sensitive and intimate matters (Steinke & Patterson-Midgley, 1996).

A number of studies have looked at nurses’ perceptions of sexual counseling. Matocha & Waterhouse (1993) examined 155 nurse’s attitudes towards discussing sexual concerns with patients and found that 69% were uncomfortable discussing sexual concerns and only 31% felt they were knowledgeable about sexuality. It was also found that 59% thought that nurses usually have a responsibility to discuss sexual concerns with patients, and this was appropriate in practice areas such as gynecology, postnatal care and mental health, but otherwise they did not routinely implement sexual counseling (Crumlish, 2004).

Shuman & Bohachick (1987) asked 50 cardiac nurses about their knowledge, attitudes, level of comfort, sense of responsibility and preparedness regarding sexual counseling of post-MI patients. The results indicated that the majority (82%) believed that sexual counseling was part of their role, but only half of these cardiac nurses (52%) routinely included sexual counseling in their practice. Similar results were found by Steinke & Patterson (1995) who examined the extent to which 171 cardiac nurses offered assessment of sexual concerns and counseling to post-MI patients. Forty-two per cent of the nurses had not assessed or approached their patients to discuss sexual concerns in the previous year, and many of the others did it in relatively few cases: 33% had offered to discuss sexual concerns but with very few of their patients (less than 2%) and another 15% with fewer than one in ten of the patients they had cared for in the last 12 months. Although cardiac nurses often make referrals to other members of the multidisciplinary team, such as doctors or cardiac rehabilitation nurses, 71% of the cardiac nurses in that study had never instigated a referral of a post-MI patient to a specialist practitioner of sexual counseling.

Thus the picture is that post-MI patients do not routinely receive sexual counseling even though concerns about sexual dysfunction become particularly important after a crisis such as an MI. Lack of information on sexuality can be frustrating to patients after MI. Vague references to sexuality can lead to insecurity confusion and depression (Yura, 1983; Shuman & Bohachick, 1987). Patient often rely on myths, misinformation, and misconception as they try to cope with sexual concerns during an illness experience.

However, several of the previous studies in the literature are relatively old and moreover they do not cover a wide range of countries and cultures. The aim of the present study is to carry out an up-to-date investigation of Greek nurses’ knowledge, comfort, ease, responsibility and practical application of sexual counseling among post-infarction patients.

Material and Methods

Data were collected by interviews conducted over three days at the 2006 cardiological conference of the Greek nursing association. Of 500 nurses enrolled in the conference, 203 (40.6%) participated in the study, of whom 78 (39.0%) were currently working in cardiac units, 16 (8.0%) in stepdown units, 57 (28.5%) in intensive care and 49 (24.5%) elsewhere. Five trained researchers carried out the interviews using a 35-item questionnaire. The first six questions recorded basic demographic information (age, gender) and data on the respondent’s nursing career (qualification, hospital and unit where currently working, years of experience in cardiac clinics). The next 13 items (based on Steinke & Patterson-Midgley, 1996) assessed the respondents’ comfort in providing information on sexuality to patients (sample item: “do you feel comfortable in discussing a post-infarction patient’s sexual concerns?”), whether they did so (sample item: “is advice on sexuality part of the rehabilitation programme after infarction?”), their perceived ability to provide advice (sample item: “do you believe that you have the training to provide advice on sexuality after infarction?”) and their perceived responsibility for giving advice (sample item: “do you believe that advising on sexuality forms part of nursing care?”). These items were answered yes or no. There followed three questions on the practice of providing advice on sexuality, after which the remainder of the questionnaire was devoted to testing the respondent’s knowledge relevant to sexual counseling after myocardial infarction. This part of the questionnaire consisted of multiple choice questions that were basically the same as those of Steinke (2000).

Statistical Analysis

The items on comfort, ability and responsibility were examined using principal components analysis with a view to constructing a summary score or scores. The analysis did not suggest the existence of clear subscales. Therefore, instead of using subscales such as those measuring comfort, responsibility and practice used by Steinke & Patterson-Midgley (1996), we took a single score – the number of “yes” answers –as an index of all aspects of the provision of sexual counseling. The internal reliability of this scale was very good (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.791). Up to two missing answers were allowed, with the scale score being multiplied up appropriately. Eleven respondents with more than two missing answers were excluded.

The questions concerning knowledge related to sexual counseling after myocardial infarction were summarized by taking the number of correct answers. In this case, missing responses were counted as incorrect but four respondents who did not answer this section at all were excluded entirely.

Scores were compared between groups using Student’s t test (for two groups) or one-way ANOVA (for three or more groups).

Results

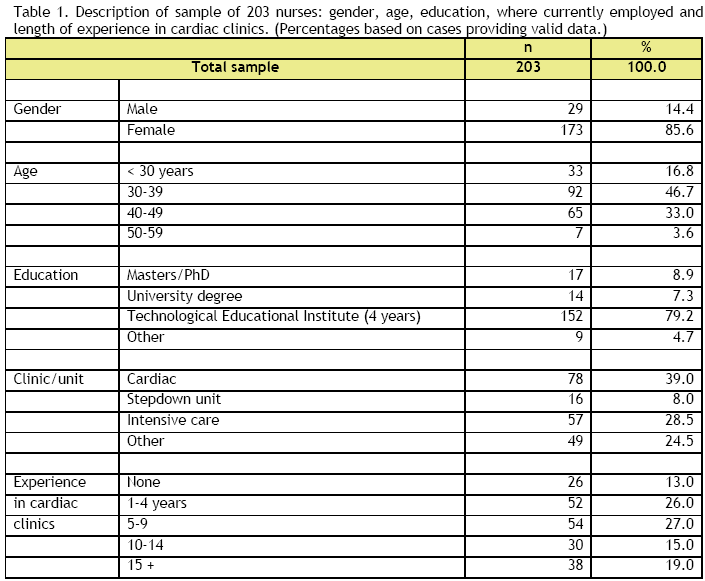

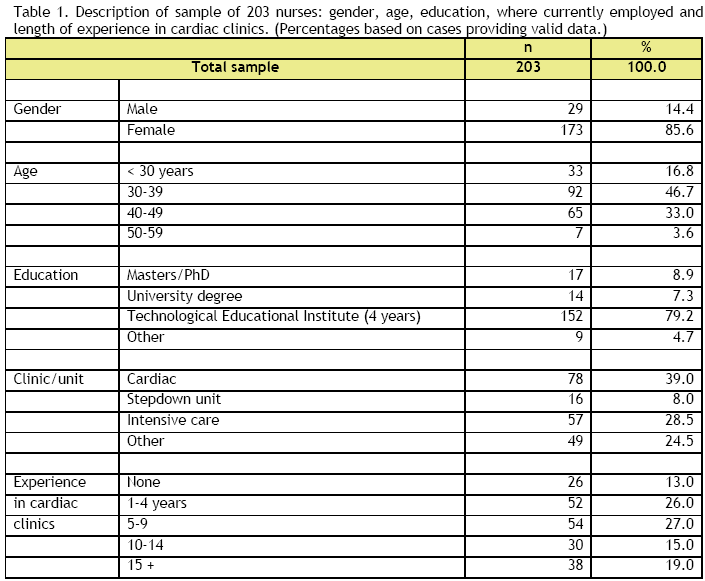

Table 1 shows the description of the 203 nurses participating in the study in terms of gender, age, education, in what type of unit they were currently working and the length of their experience in cardiac clinics. Respondents were employed in 30 different health care institutions, the greatest number from any one being 35 (16.8% of the sample). Their mean age was 36.9 years (standard deviation 7.0, range 21-56 years).

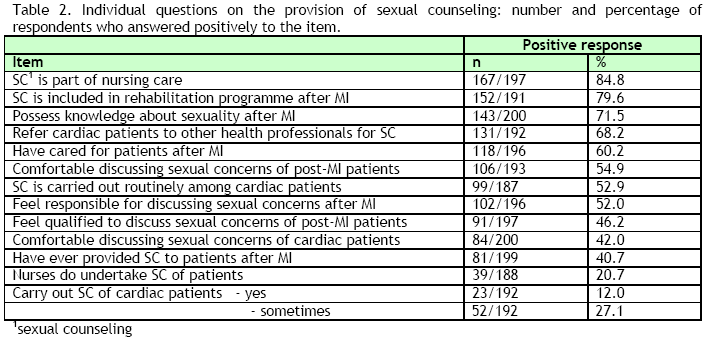

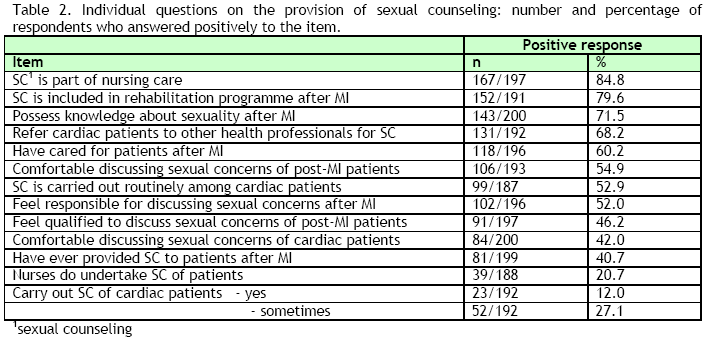

Table 2 shows responses to the individual questions on providing sexual counseling. Although the large majority (84.8%) agreed with the general principle that sexual counseling forms part of nursing care, the practice appeared to be quite different. Only 20.7% said that nurses do in fact undertake sexual counseling and although 39.1% said that they carry it out themselves, most only did so “sometimes”. Less than half of the respondents (42.0%) felt comfortable in discussing the sexual concerns of post-MI patients and only 46.2% felt qualified to handle such a discussion - although rather more (71.5%) claimed that they possessed the technical knowledge about sexuality after MI.

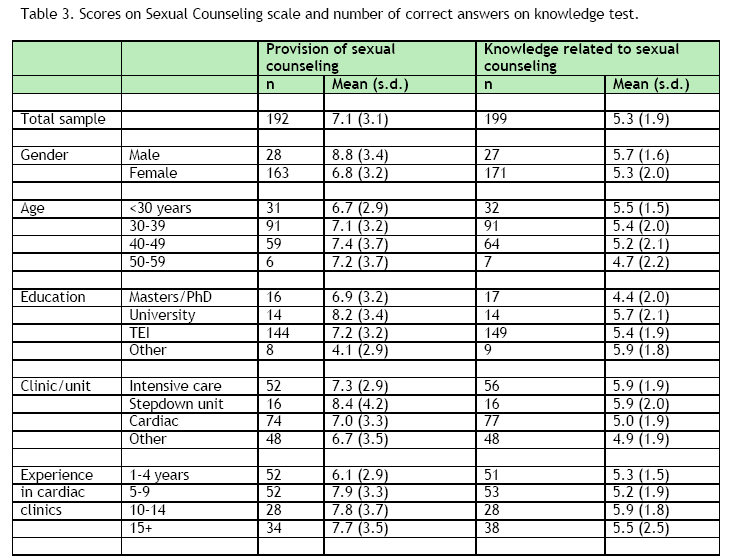

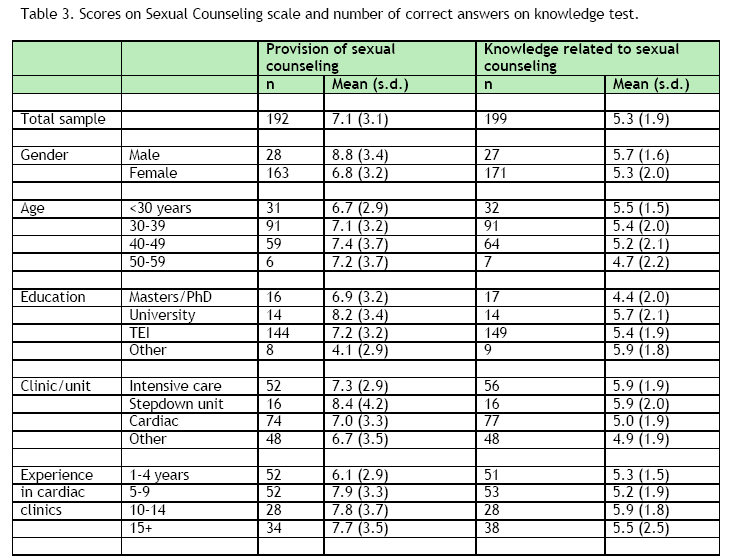

Table 3 shows mean scores on the scale of Provision of Sexual Counseling constructed from the above items, in relation to demographic data and the data on the respondent’s nursing career. Scores were statistically significantly lower for females than for males (P=0.004, t test) and for nurses with little experience in cardiac clinics compared to those with at least 5 years (P=0.018, ANOVA). In other words, male gender and longer experience in cardiac clinics were associated with a greater feeling of comfort, ability and responsibility in providing sexual counseling. Also, the few nurses with “other qualifications” had significantly lower scale scores than the rest (P=0.035, ANOVA). Scores were not significantly related to the other items in Table 3 (P>0.30, ANOVAs).

Concerning the practice of sexual counseling, the general question “Do nurses undertake discussing patients’ sexual concerns and suggesting solutions?” was answered positively by only 20.7% (39/188) respondents and the specific question “Do you carry out sexual counseling of cardiac patients?” was answered “yes” by only 12%, “sometimes” by 27% and negatively by 61%. It was generally felt that few specialized cardiac nurses included sexual rehabilitation in their counseling: 70.4% of respondents said that only about 1 in 10 cardiac nurses did so. The commonest practice may be to refer patients to other health professionals for counseling. More than half the respondents (106/192, 55.2%) said that they referred patients to doctors (cardiologists or general practitioners), 28.1% to psychologists, 28.1% to specialized nurses and 17.2% to sexologists (multiple responses allowed). However, we do not know how often referrals take place and whether advice is actually given in the end. In fact, the opinion of more than half of our respondents (115/201, 57.2%) was that only about one in ten post-MI patients receives advice about resuming sexual activity. Finally, among the nurses who answered a question about who instigated conversation about sexual concerns - and may therefore be presumed to be the ones who are from time to time involved in such discussions - only 9.7% (12/124) said that they themselves brought up the topic.

The mean numbers of correct responses to the items testing knowledge related to sexual counseling are also shown in Table 3. Scores varied statistically significantly only in relation to the unit in which the respondent was currently working (P=0.01, ANOVA). Respondents from intensive care units and stepdown units had higher mean scores than respondents from cardiac units and other units. Scores were not significantly related to the other items in Table 3 (P>0.17, ANOVAs).

Discussion

The resumption of sexual activity is an important aspect of quality of life for many cardiac patients. Managing the fears and worries of patients and their partners is an important part of educating the patient, yet health professionals are too often unwilling to discuss such a personal issue with the patient (Matocha & Waterhouse, 1993; Williams, et al., 2001; Shuman & Bohachick, 1987),

This study found that a rather low proportion of the participating nurses themselves carry out sexual counseling (12%, plus another 27% who do it sometimes) and that they perceive that this is true of the profession in general, since the majority thinks that only about 1 in 10 provides counseling. These results agree with other studies on the implementation of sexual counseling (Matocha & Waterhouse, 1993; Steinke & Patterson-Midgley, 1996). Opinion was divided about whether sexual counseling falls within the nurses’ responsibilities: 52% thought that it did, but 48% that it did not. This is also in agreement with other studies (Shuman & Bohachick, 1987), as is the fact that 58% did not feel comfortable discussing cardiac patients’ sexual concerns (see Matocha & Waterhouse, 1993). Against this background, it is not surprising that only 41% had ever assisted an MI patient by providing sexual counseling. Similarly, Matocha & Waterhouse (1993) found that one third of their sample of nurses had never aided MI patients by discussing their sexual concerns. Results of Baggs & Karch (1987) are also along the same lines. These studies suggest that nurses do not feel competent to provide sexual counseling and as a result are reluctant to do so. Sexual counseling is frequently overlooked or ignored in rehabilitation programmes for cardiac patients, not because there is a lack of literature or guidelines on this topic, but because of the nurses’ discomfort at entering this sensitive area even though they may agree in principle that they have some responsibility for providing sexual counseling (Shuman & Bohachick, 1987; Matocha & Waterhouse, 1993). However, feelings of ease and responsibility are not sufficient to ensure that sexual counseling is carried out in practice (Williams et al., 2001; Shuman & Bohachick, 1987; Matocha & Waterhouse, 1993; Steinke, 1998; Steinke, 2002; Steinke & Patterson-Midgley, 1996).

Even when the exchange of information concerning sexuality post MI is accepted as an essential part of the nurse’s role (Steinke, 2000; Katz, 2003), the evidence suggests that nurses are not assessing each patient’s need nor are they giving health advice about sexual concerns (Gamel et al, 1993; Steinke & Patterson, 1995; Albarran & Bridger, 1997; Albarran, 2000). Despite the increasing complexity of nurses’ education and experience, the literature indicates that many nurses may not possess adequate knowledge and skill in educating clients about sexuality (Bennet, Demays & Germain, 1993; Billhorn, 1994; Gamel, Davis & Hengeveld, 1993; Hughes, 1996; Kautz, Dickey & Stevens, 1990; Marwick, 1999, Meerabeau, 1999; Steinke & Patterson-Midgley, 1996). Because of the post-MI patient’s life-threatening illness, sexual counseling is understandably given a low priority during the acute phase of the illness (Albarran, 2000). Unfortunately, it also remains a low priority in the rehabilitation phase of the illness (Steinke & Patterson, 1995; Crumlish, 2003).

However, such information helps to alleviate sexual concerns between the patient and his or her partner, and to clarify misconceptions that engaging in sexual activity after suffering an MI may lead to further myocardial injury or death (Steinke & Patterson-Midgley, 1996; Arino-Norris, 1997).

Sexual counseling is a vital part of nursing practice. Nurses have long assumed educative and supportive roles as they try to meet the educational and psychological needs of post-MI patients (Steinke & Patterson-Midgley, 1998; Crumlish, 2003). Lack of time, the critical severity of MI patients, the noisy CCU and lack of privacy, as well as the nurse’s embarrassment, have all been identified as barriers to initiating sexual counseling in CCU to post-MI patients (Steinke & Patterson-Midgley, 1998; Crumlish, 2003).

Although these barriers are real concerns for nurses, sexual counseling should be introduced early in the post-MI patients’ hospitalization and should continue throughout their hospital stay and after discharge (Steinke, 2002). Teaching can begin early in the CCU as part of nursing assessment by CCU nurses, and rehabilitation nurses can assess what has been discussed, plan future instruction and arrange for post-discharge follow-up (Steinke, 2002). This is particularly important, as concerns about resuming sexual activity can become more apparent after discharge when patients are returning to their usual activities (Wang, 1994).

Education programmes and teaching media are essential to equip nurses with the knowledge and skills for providing sexual counseling (Albarran & Bridger, 1997; Savage, 1998). Practice with sexual counseling in a classroom setting could serve to increase nurses’ comfort levels. An increased awareness of the type of information to be covered and the provision of teaching tools for use in their clinical area should improve nurses’ comfort with this topic. Steinke and Patterson-Midgley (1998) believe that these strategies could also influence the social norm in CCU and make it more acceptable for nurses to discuss post-MI patients’ sexual concerns with them.

The guidelines also seek to increase the understanding, competence and confidence of nurses by developing their knowledge and skills in a way that will enable them to engage effectively with patients in responding to their sexual health needs (Albarran, 2000).

Coronary care nurses must realize that they can play a pivotal role in educating post-MI patients in this sensitive area and overcome their apparent reluctance to incorporate this information in post-MI education sessions. It must be remembered that not all post-MI patients will be interested or ready to discuss sexual concerns when approached by nursing staff, especially in the acute care setting, and their wishes must be respected (Crumlish, 2004). Nurses must be aware of what resources and aids are available and be creative in using them to ensure that the patient’s sexual concerns are addressed. Sexual counseling, started in the acute care setting and continued in the community setting, is essential to meet the sexual integrity and quality-of-life needs of the post-MI patient and his or her partner.

3671

References

- American Heart Association. 2002 Statistical Update. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association; 2002

- Steinke EE, Swan HJ. Effectiveness of a videotape for sexual counseling after myocardial infarction. Res Nurs Health 2004; 27:269-280

- Briggs LM. Sexual healing: caring for patients recovering from myocardial infarction. Br J Nurs 1994; 3:837-42

- Crumlish B. The nurse’s role in post-MI patient education: incongruent perceptions among nurses and patients in a general hospital in Northern Ireland. All Ire J Nurs Midwif 2003; 2(11):29-39

- Albarran J, Bridger S. Problems with providing education on resuming sexual activity after myocardial infarction: developing written information for patients. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 1997; 13: 2-11

- Steinke EE, Patterson-Midgley P. Sexual counseling of MI patients: nurses’ comfort, responsibility and practice. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 1996; 15:216-23

- Steinke EE. Sexual counseling after myocardial infarction. Am J Nurs 2000; 100:38-44

- Katz A. Sexuality after hysterectomy: a review of the literature and discussion of nurses’ role. J Adv Nurs 2003; 42:297-303

- Gamel C, Davis B, Hengeveld M. Nurses’ provision of teaching and counseling on sexuality: A review of the literature. J Adv Nurs 1993; 18:1219-1227

- Steinke E, Patterson P. Sexual counseling of MI patients by cardiac nurses. J Cardiovasc Nurs 1995; 10:81-7

- Albarran J. Time to embrace the concepts of sexuality and sexual health in critical care nursing practice? Nurs Crit Care 2000; 5: 213-214

- Matocha LK, Waterhouse JK. Current nursing practice related to sexuality. Res Nurs Health 1993; 16:371-8

- Crumlish B. Sexual counselling by cardiac nurses for patients following an MI. Br J Nurs 2004; 13: 710-713

- Shuman N, Bohachick P. Nurses’ attitudes towards sexual counselling. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 1987; 6:75-80

- Yura H, Walsh MB. Human needs and the nursing process. Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1983

- Steinke EE. A videotape intervention for sexual counseling after myocardial infarction. Heart Lung 2002; 31:348-54

- Williams T. Talking about cancer and sexual health. Practice Nurs 2001; 12:319-22

- Baggs JG, Karch AM. Sexual counselling of women coronary heart disease. Heart Lung 1987; 16:154-7

- Steinke EE, Patterson-Midgley P. Perspectives of nurses and patients on the need for sexual counseling of MI patients. Rehabil Nurs 1998; 23:64-70

- Bennet J, DeMays M, Germain M. Caring in the time of AIDS: The importance of empathy. Nurs Admin Q 1993; 17(2): 46-60

- Billhorn D. Sexuality and the chronically ill older adult. Geriatr Nurs 1994; 15:106-108

- Hughes M. Sexuality issues: Keeping your cool. Oncol Nurs Forum 1996; 23:1597-1600

- Kautz DD, Dickey CA, Stevens MN. Using research to identify why nurses do not meet established sexuality nursing care standards. J Nurs Qual Assur 1990; 4:69-78

- Marwick C. Survey says patients expect little physician help on sex. J Amer Med Assoc 1999; 281:2173-2174

- Meerabeau L. The management of embarrassment and sexuality in healthcare. J Adv Nurs 1999; 29:1507-1513

- Arino-Norris N. Sexual concerns after an MI. Am J Nurs 1997; 97(8):48-9

- Wang WW. The educational needs of myocardial infarction patients. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs 1994; 9(4):28-36