Keywords

Nurse education, programme evaluation, realistic evaluation

Introduction

During last decades realistic evaluation in nurse education has received a great deal of intention. Though the term ‘realist evaluation’ has its root in realism, a school of philosophy which asserts that both the material and the social worlds are ‘real’ and can have real effects however a theory called “realistic evaluation” was developed by Tilley and Pawson in 1997. More in detail, this theory was concerned with the identification of underlying casual mechanisms and how they work, under what conditions. Furthermore, a realist approach has particular implications for the design of an evaluation and the roles of participants. For example, rather than comparing changes for participants who have undertaken a program with a group of people who have not (as is done in random control or quasi-experimental designs), a realist evaluation compares mechanisms and outcomes within programs. It may ask, for example, whether a program works differently in different localities (and if so, how and why); or for different population groups (for example, men and women, or groups with differing socio-economic status). Therefore, its concern is with understanding causal mechanisms and the conditions under which they are activated to produce specific outcomes. Principles of realistic evaluation were praised and used in education since areas such as participants’ values, experiences, context, learning mechanisms and culture are thoroughly explored through this approach [1].

The review of the literature reflects a continuous effort to design and analyse a variety of evaluation processes and models in nurse education [2-6]. In United States systematic programme evaluation is a requirement for accreditation in order to assure educational effectiveness and public accountability [7]. Furthermore, evaluators strive towards attending to students’ voice for enhancing effectiveness and excellence of evaluation methods [8,9]. However, various implications for evaluation and its application to practice were yield [6]. Influential discussions on evaluation in education portray a strenuous effort to find a workable model for evaluation in practice. The outcome of these attempts suggested that finding a workable model for evaluation is not an easy task and often leads equally to frustration and enlightenment. It is also the reason that many of the evaluation models have been subjected to serious criticism and that evaluators have experienced disappointing difficulties in applying them in practice [10-12].

Mixed methods were appraised for their ability to integrate different concepts and theories and create complex and comprehensive evaluation designs. Issues of flexibility, synthesis, naturalism in evaluation and alternative paths of non traditional evaluation approaches considered by many evaluators as the cornerstone of developing workable and meaningful evaluation models, and various theories developed that involve mixed evaluation methods [13,14]. These advancements led to an intellectual shift towards reality and realistic exploration of phenomena in the field of educational evaluation.

This new era included concepts of creativity and discovery. Patton in early ‘90s motivated contemporary evaluators to use imagination, holistic perspectives and inductive processes rather than predetermined models in the practice of evaluation [14-16]. The significance of people, context, structures, mechanisms and values were also indicated in real world evaluation by many authors [17-21]. The concepts of humanising and personalising the evaluation process appeared on the modern evaluation scene. Evaluation in real settings became an ongoing concern for the researchers and realistic evaluation a new paradigm which can provide explicit knowledge and meaningful results for programme evaluation [22,23].

In the light of these developments, the establishment of qualitative methods in evaluation was appraised since they have proven their utility to practising evaluators, their distinctiveness to theorists and their attractiveness to readers [24]. This is an important point for evaluation in social science, especially when evaluation methods focus on real-life settings, which are idiosyncratic and unique such as education. For this purpose, issues of flexibility, openness, and inductive processes to evaluation based on realism appeared to be the most appropriate for planning the evaluation method.

The aim of this study was to highlight the benefits of using the principles of realistic evaluation in nurse education. It further attempt to provide evaluation guidelines for those researchers who would like to adopt flexible evaluation approaches based on a real – world educational context.

Methodology

At the beginning of the present study a method of traditional, experimental evaluation design was used. However, initial results showed that this design produced partly useful findings. Areas such as participants’ values, experiences, context, learning mechanisms and culture remained unexplored. In the light of this inadequacy, a reconsideration of the method and the evaluation approach be used was made. The focus of the study shifted from a quantitative to a qualitative perspective. This involved a re-interpretation of all the original data collected at the time of implementation together with new retrospective data and personal reflection. Principles of realistic evaluation were praised and used.

The process of evaluation applied on an English-speaking Quality Assurance module which developed within the frame of a post graduate nursing course and addressed to twelve post graduate Greek nurse students. The evaluation strategy consisted of two phases. The first phase focused on traditional evaluation approaches. This included self – reported structured questionnaires which were administered to the programme participants before and after the training in order to monitor changes in participants’ knowledge and attitudes. The findings at this phase although offered some insights on nurses’ knowledge and attitudes, did not provide information about holistic elements of the educational process such as participants’ values, experience, personal attributes, culture and context. In this respect, the need for further evaluation was highlighted.

In the second phase of evaluation the researchers focused on shedding light on the above mentioned holistic elements as these appeared throughout the programme process. Consequently, evaluation followed the principles of realistic evaluation as these reported by Patton14 and further discussed by Pawson and Tilley.1 According to these, consideration should be given to the programme process as well as to context, mechanisms and outcomes of the programme which emerge in each programme stage. For this reason the educational programme process was analysed and it became apparent that the programme development and implementation fell naturally into the following six consecutive stages:

1. Studying the participants in their social and professional context

2. Developing a support network

3. Involving the participants in the programme

4. Developing the programme

5. Implementing the programme

6. Evaluating the programme’s outcome

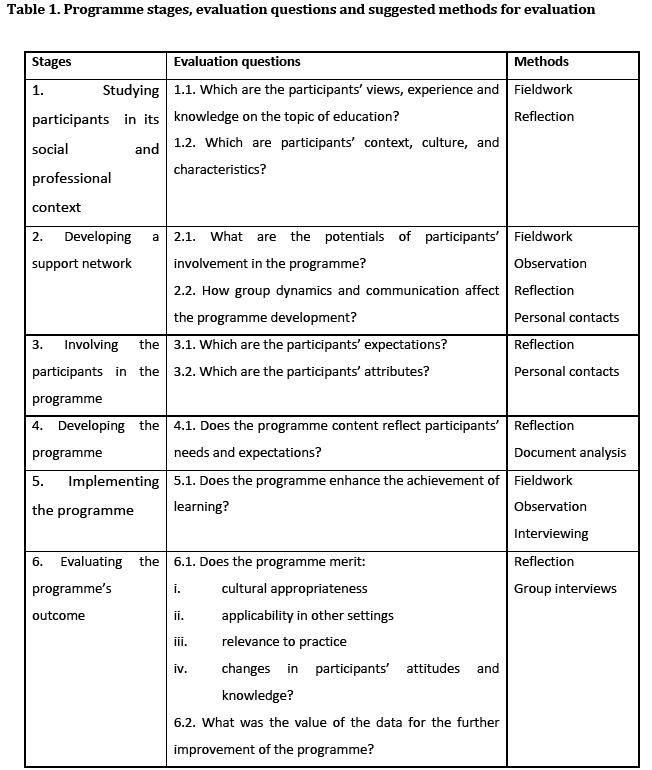

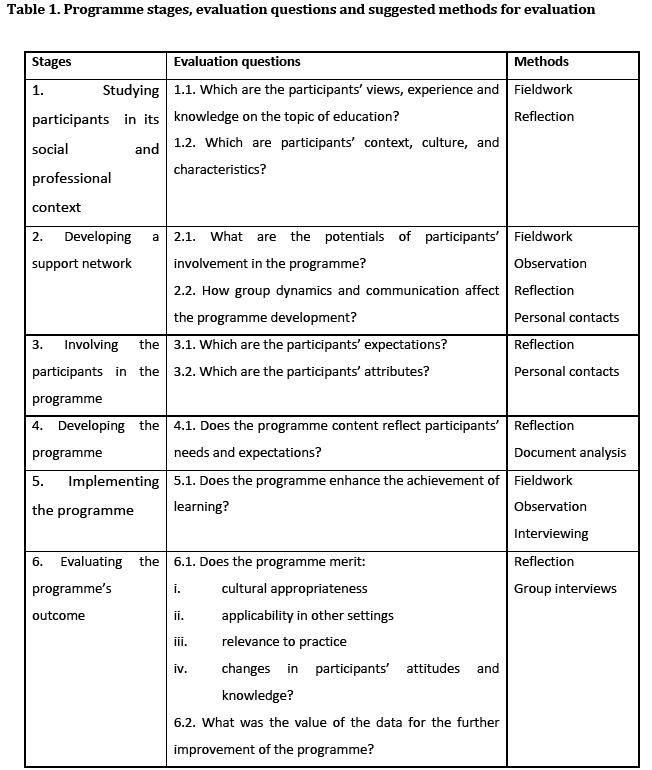

Each of these stages was seen as a distinct activity which can be described and evaluated in terms of its process. For each of the process stages, the key evaluation questions were specified. These dealt with the information needed to illuminate the qualitative elements of the educational process such as context and experience. At the second evaluation phase the data required to answer the questions were of a qualitative nature, although in some cases quantitative data from the first evaluation phase were applicable. Data were viewed through personal insights, empathy, holistic and dynamic perspectives. The notions of research pluralism, design flexibility, combination of different research approaches and Patton’s pragmatism, [14] which separates the world of theory from the world of practice were the focus of the researchers throughout the evaluation of each process stage. Table 1 presents the programme stages, the evaluation questions and the methods suggested in the proposed evaluation design.

At the first evaluation phase data collected from the twelve programme participants. Structured self-reported questionnaires measuring the participants’ knowledge on the topic of education were disseminated prior to the programme implementation. In addition two sets of structured questionnaires focusing on participants’ attitudes and knowledge were disseminated to the participants before and after the educational intervention.

At the second evaluation phase data were collected through document analysis, personal contacts, fieldwork, observation, reflection and interviewing. The notions of research pluralism, design flexibility, combination of different research approaches and Patton’s pragmatism, were on the focus of the researchers throughout the evaluation of each process stage.

Results

Evaluation of the first process stage was limited to the nurses’ knowledge about quality. At the first evaluation phase, self-reported structured questionnaires were used. The resultant data provided partial answers to the evaluation questions (Table 1). For example, the findings from the structured questionnaires suggested that the influence of social and working contexts might have some effects on nurses’ views and knowledge about quality of care. They did not however, provide precise details about these contextual factors and their likely impact on the programme and on stakeholders’ decisions. The evaluation process at the second phase focused on studying the programme participants within their social and professional context. For this purpose further fieldwork was undertaken, employing methods derived from the qualitative research paradigm, such as reflection. The findings demonstrated that culture, context and people’s specific qualities are important factors that should be taken into account if we want to develop successful educational programmes.

The purpose of the second process stage concerned with the development of a support network for facilitating programme implementation. Issues of interpersonal interactions and group dynamics were central to this stage. These issues remained unexplored in the first evaluation phase. For this reason, in the second evaluation phase, methods of observation, reflection, personal contacts and fieldwork were applied. Network activities were explored taking into account people’s interactions and group dynamics. Findings demonstrated that participants who were living in rural areas were facing problems regarding the accessibility of the actual programme location and the communication with programme stakeholders. Findings emphasised more structured communication patterns, appreciation of communication styles and acknowledgement of different cultural attitudes. These facets are essential or supporting the tasks of the network and facilitating the programme process.

In the third process stage, the purpose was the exploration of participants’ expectations from the programme. At the first evaluation phase a self-reported structured questionnaire was used. The data although provide some knowledge for the further development of the programme they did not reveal issues regarding the individuals’ characteristics and idiosyncrasies. In the second evaluation phase researchers focused on the involvement of the participants in the programme. Methods of personal contact and reflection were used for this purpose. The findings revealed that people’s specific attributes, personal values and prior educational experiences are important in designing appropriate educational programmes. For this reason, these specific elements should be examined and acknowledged throughout programme development.

The purpose of fourth process stage was to explore issues related to programme development. Meeting the participants’ needs and expectations was central to this stage. These issues were not sufficiently explored in the first evaluation phase. For this reason, in the second evaluation phase, reflection and document analysis were used. The findings valued the stakeholders’ and participants’ philosophy and values in developing the programme and in paving the way to programme implementation. The data also demonstrated that evaluation has not always to be a complex process. Evaluation in the real world can be simple for certain purposes and stages.

The purpose of the fifth process stage was to examine the attributes of the programme itself. Structured questionnaires were used. The resultant data revealed little about real programme implementation and people’s experiences at that stage. For example, the issue of the English language –in which the module was taught– was raised by the participants and appeared to relate to learning process. However, data did not provide more explicit knowledge in the achievement of learning. The second evaluation phase focused on exploring programme implementation aspects through the participants’ eyes. Reflection, observation, depth interviewing, and fieldwork were found to be the most appropriate methods for this purpose. The findings revealed aspects of programme applicability, appropriateness and relevancy to practice. Issues of environment and culture and their influence to the achievement of learning were mentioned by the participants. It appeared that traditions, ways of living and backgrounds affect the process of learning and data on these issues should be taken into account when programme implementation is planned.

The last process stage concerned with programme’s outcomes and improvement. Self-reported structured questionnaires were employed at the first evaluation phase to obtain outcome data in a pre-test post-test design. Data provided limited insight on programme outcome and improvement for three reasons. Firstly, the pre-post design was subject to a number of validity threats which cast doubt on the relationship between outcomes and process. Second, the numbers involved in the programme were small and thus any estimates of change in outcome measures would have very large confidence intervals. Finally, the data collection instrument did not address personal factors, such as people’s experiences, beliefs and feelings about the programme. The second evaluation phase focused on collecting outcome data, which would enlighten areas of programme improvement as viewed by the participants. Depth interviewing and reflection were used for this purpose. Findings reflected the participants’ experiences and stressed the importance of culture, context and of people’s unique profiles in successfully developing and introducing programmes.

Discussion

From the presentation of the evaluation methods used, it may be seen that for most of the stages a similar pattern of evaluation developed. The initial deficient exploration gave rise to consideration of alternatives and finally to selection of a more appropriate exploration. The terms “deficient” and “appropriate” have been carefully chosen in order to demonstrate the researcher’s position in relation to the evaluation design. The initial evaluation phase is defined as “deficient” because although it did provide some useful findings and revealed issues for further consideration, in most of the cases it failed to provide integrated knowledge and complete answers to important evaluation questions. The second phase of evaluation is defined as “appropriate”, because it is important to underline the concept of “personalising” in the application of process evaluation and to favour at the same time “methodological appropriateness” in evaluation.14 These concepts stand for the pragmatic orientation of qualitative inquiry as explored by Patton who calls for flexibility in evaluation rather than the imposition of predetermined models.14 They also stand for the field of education, which involves historical backgrounds, cultures, social needs, personal preferences and ambitions and thus makes each educational programme a unique endeavour.25 The two evaluation phases may be seen as forming parts of a continuum of approaches which was called the “artificial-realistic continuum”. This is shown schematically in Table 2 (The “artificial – realistic continuum” in process evaluation).

It should be noted that the Keywords occurring in all process stages refer to context and people. These terms embody concepts of culture, experience, values and attributes, which have been highlighted throughout the analysis and evaluation of the six process stages. The emergence of these Keywords not only triggered the inception of alternative paths but also explicitly determined their content, ensuring that they would address real life, natural contexts (social and professional), real characteristics and real experiences.

Furthermore, one of the aspects of evaluating the real-world of a situation was to examine how the participants moved and developed in the frame of the programme. This part of evaluation which follows the principles of process evaluation as described by Patton, identified potential changes which may not be caused by the programme itself [14]. Group dynamics, communication patterns and participants’ feelings were taken into consideration. It was highlighted thus, how participants might have been changed or influenced by others throughout the programme. The findings were viewed under these changes and thus the researcher was enabled to consider issues of maturation. The utilisation of different methods of data generation in the evaluation design minimised the effect that the pre-test might had to the findings and advanced the credibility of the findings through triangulation of data sources [14]. During the course of the study new understandings arose through a process very similar to the one described here of searching for a suitable strategy to deal with “real world” evaluation. Pawson and Tilley, the “Emergent Realists”, believe that realism can be a valuable foundation for evaluation and can provide an important service to the field of evaluation with greater promise than the paradigm war of the past decades [1]. The realist approach incorporates the realist notion of a stratified reality with real underlying generative mechanisms. Using these core realist ideas and others, Pawson and Tilley build their realistic evaluation around the notion of context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) pattern configurations. In their view, the central task in realistic evaluation is the identification and testing of CMO configurations. This involves deciding what mechanisms work for whom and under what circumstances [1].

In particular the shift from traditional evaluation design towards a more comprehensive approach to evaluation as reported in this paper was similar to that described by Pawson and Tilley [1]. The focus of evaluation shifted on the programme process within a particular cultural, social and professional context. The programme process was broken down into a series of sub-processes. This is described by Pawson and Tilley in 1997 as a broad feature of the realist understanding of programme mechanisms [1]. Analysis and evaluation of programme sub-processes in this way is considered beneficial because it:

• Uncovers areas of interest in programme evaluation which might otherwise be neglected (i.e. issues of social and cultural context unravelled in stage one)

• Identifies and examines mechanisms which are different for each particular sub-process (i.e. communication and group dynamics patterns identified in stages two and three)

• Identifies and examines participants’ characteristics and experiences which are different (or influence differently) for each particular sub-process (i.e. human interactions and peoples’ attributes identified and examined in stages one, three and five)

• Identifies and examines sets of outcomes which are different for each particular sub-process (i.e. outcomes related to programme implementation identified in stage five and outcomes related to participant’s changes identified in stage six)

• Identifies and examines the specific context underlying each sub-process (i.e. issues of specific contexts and settings identified in stages one and five)

• Allows appropriate explanations, recommendations and programme improvements (i.e. recommendations on specific standard setting for optimal programme process were made in stage six)

• Uncovers underlying concepts of the reality in which the programme operates (i.e. issues about environment and culture unravelled in stage five)

In this respect, the principles of realistic evaluation were applied with benefit to the evaluation of the programme.

Recommendations for the practice of evaluation

In the study described in this paper, the experience of searching to find a workable model for evaluation in practice led to an intellectual shift towards reality and realistic exploration of phenomena. This development emphasized holistic perspectives, flexibility, creativity and discovery in the practice of evaluation. Dynamic elements such as experiences, values, context and mechanisms were appraised in the context of the real-world evaluation [1,13,17,19,25-28].

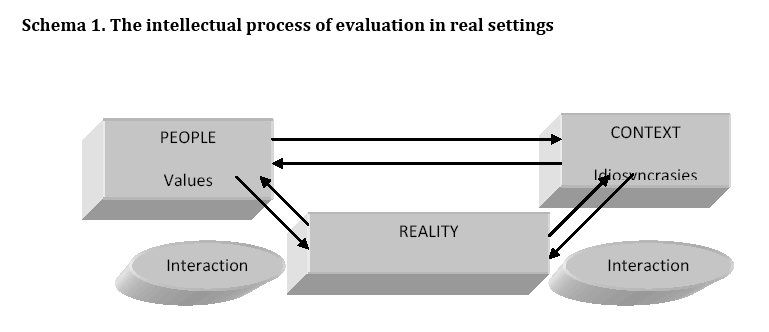

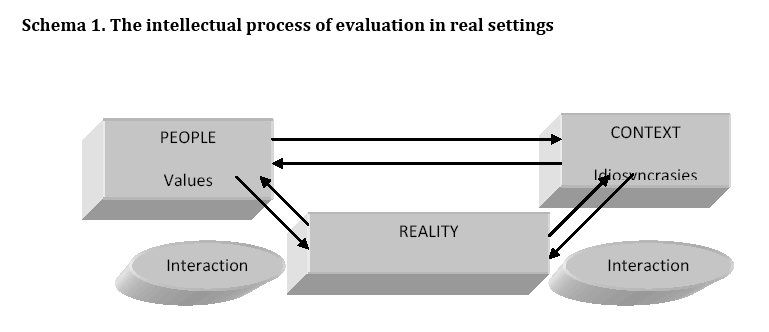

Experience gained throughout the course of this study, led to appraisal of the recently emerging debates on evaluation and consideration of its different aspects and their application to the real world. A schematic representation of this intellectual process is shown in schema 1.

Schema 1: The intellectual process of evaluation in real settings

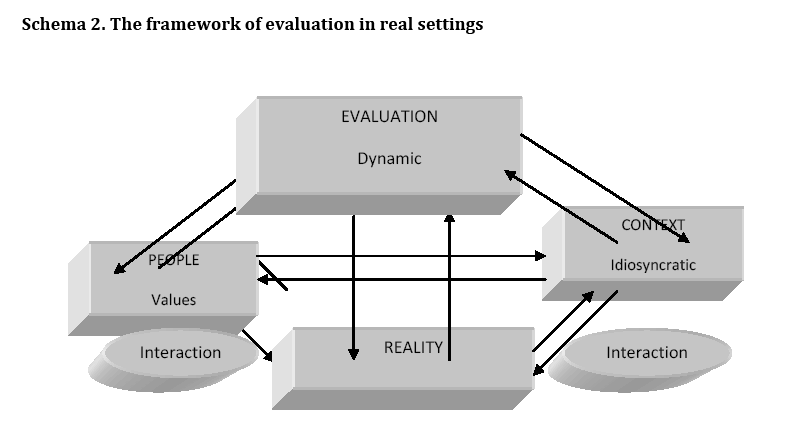

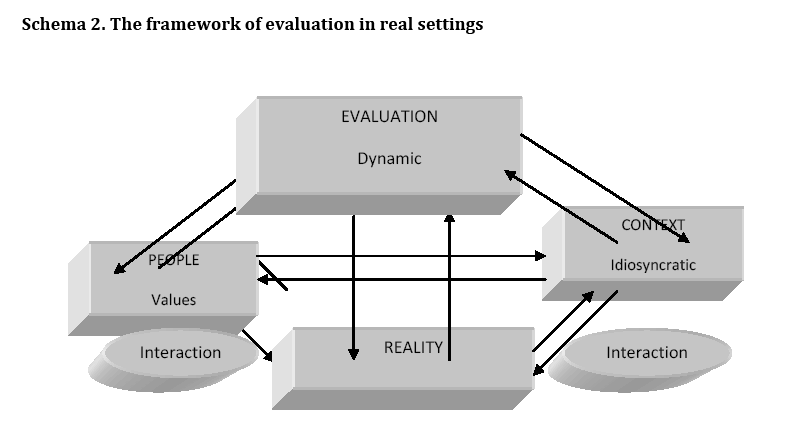

Reality is dynamic and constantly interacts with people and context. Evaluation in this context encompasses energetic and living components. Thus, evaluation in real settings should be dynamic representing the complex framework of schema 2.

Schema 2: The framework of evaluation in real settings

In order to make this framework usable in practice, broad guidelines for evaluation in real settings are presented in the next paragraphs. The recommended guidelines refer to different programme stages:

The first stage of evaluation is to identify the nature and the purpose of evaluation. This involves the analysis of the topic of evaluation and its elements. A thoughtful exploration of the purpose of the evaluation in relation to the topic and the stakeholders is taking place. At this stage it is important to consider the stakeholders and those who are going to use the evaluation findings.

The second stage is to consider the type of inquiry which would be more suitable for the evaluation. The nature of the topic and the purpose of evaluation determine the type of inquiry which will be used to frame the evaluation. The evaluator, who decides to adopt an approach based on principles of realistic evaluation, will be considering the broad objectives of the evaluation, such as whether to seek for some kind of regularity, classification of cases or CMO configurations.

The third stage is the selection of methods. This stage requires flexibility and creativity and access to the range of skills needed in order to employ the selected methods. Considering and anticipating possible validity threats are of significant importance for selecting the appropriate methods and for effectively applying them in the evaluation context.

The application of methods is the fourth stage which requires skill, sophistication and creativity. Expertise required generating, analysing and interpreting the data, taking into account the reflexive nature of this process.

The fifth stage is the utilisation of findings from stakeholders, interested parties and other evaluators. This is an interactive process and involves communication, dissemination of findings and specific recommendations for improving the evaluated programme or situation.

The final stage involves the application of corrective actions and the programme’s improvement. This necessitates consensus and common understanding between stakeholders and evaluators concerning the evidence which the evaluation has produced. A further stage of evaluation, which is recommended, is the dissemination of the evaluation strategy used and its application in similar contexts. The purpose of this stage is the elaboration of the process and the advancement of evaluation theory in real settings.

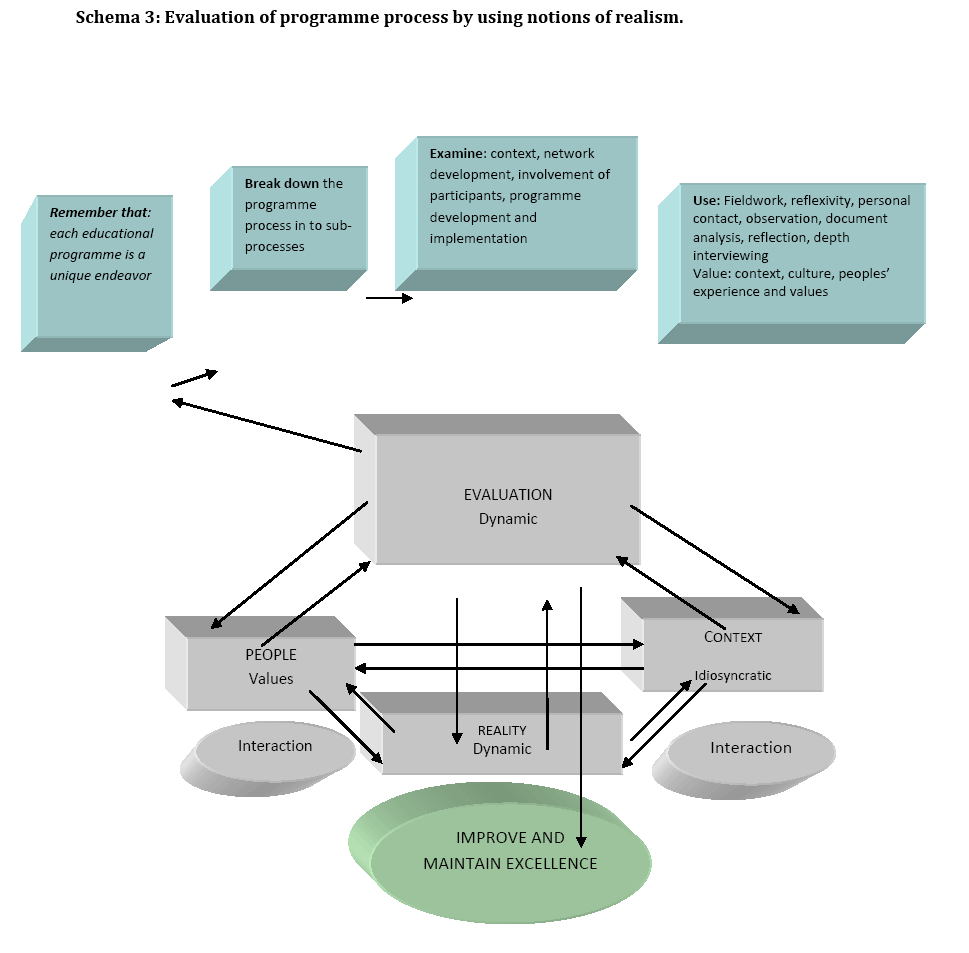

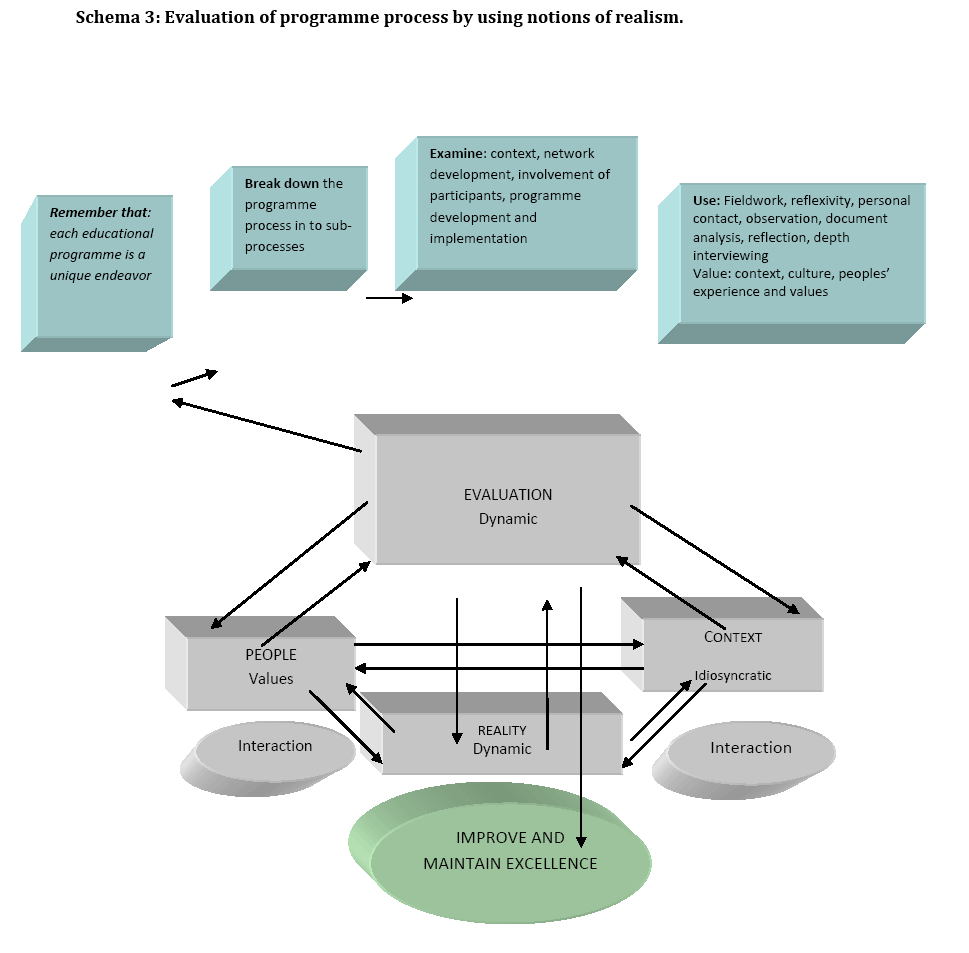

Although the evaluation described in this paper was confined to a single educational intervention, the findings carry some suggested policy implications for education providers. The active involvement of the programme stakeholders, the exploration of the context, culture and the participants’ unique profile is critical throughout the programme stages. This may include a specific standard setting which should focus on programme’s appropriateness, setting’s applicability, practical relevance, and feasibility, conformity with contexts and participants’ expectations and experience. Central to these are the evaluators’ unique qualities and personality. The interplay between the stakeholders’ and the evaluators’ idiosyncrasy will give to the evaluation a unique character which will lead to useful and meaningful findings. This approach to evaluation can provide a sound basis for programme reform and programme accreditation. Evaluation of programme process and sub-processes by using notions of realism, methods of fieldwork, reflexivity, depth interviewing, observation, values’ exploration, involvement of stakeholders and group dynamics may support continuous programme reform and improvement, as clearly demonstrated throughout the six stages of the present programme (Table 1) and presented in schema 3. Accreditation mechanisms may also be enhanced by applying realistic evaluation approaches, since elements of realistic evaluation such as described above are essential for improving and assuring excellence in nursing education.

Schema 3: Evaluation of programme process by using notions of realism.

Conclusion

Experience showed that realism can be a valuable foundation for evaluation, with its assertion that real processes are at work and the relationship between these processes and their outcomes can be described. As Pawson and Tilley put it, realism can provide an important service to the field of evaluation with greater promise than the paradigm war of the past decades.

Values inquiry, involvement of stakeholders and methods of personal contact, fieldwork, reflection and reflexivity are central to realistic evaluation. Consideration of realistic evaluation as a paradigm which cannot be value-free may bring new developments in evaluation inquiry. Such developments are likely to produce a more credible and meaningful portrait of social reality and define more explicitly the role of realistic evaluation in it.

2633

References

- Stake R. The countenance of educational evaluation. In: Hamilton D., et al. Beyond the numbers game. Macmillan Education, 1967; 146-155.

- Stufflebeam DL. Educational Evaluation and Decision Making. Peacock Publishing, Itasca. Illinois, 1971.

- Horsley A, Battrick C. Promoting excellence in children's nursing practice. Br J Nurs 2010;19(19):1213

- Kenworthy N, Nicklin P. Teaching and Assessing in Nursing Practice. An experiential approach. Eds., Scutari Press. London, 1989.

- Leibbrandt L, Brown D, White J. National comparative curriculum evaluation of baccalaureate nursing degrees: A framework for the practice based professions. Nurse Education Today 2005; 25 (6):418-429.

- Pross AE. Promoting Excellence in Nursing Education (PENE): Pross evaluation model. Nurse Education Today 2010; 30 (6): 557-561.

- Cook M, Moyle K. Students? evaluation of problem-based learning. Nurse Education Today 2002; 22 : 330-339.

- Rolfe G. Listening to students: course evaluation as action research. Nurse Education Today 1994; 14 (3): 223-227

- Whiteley SJ. Evaluation of nursing education programmes-theory and practice. International Journal of Nursing Studies 1992; 29 (3):315-323.

- Parahoo K. Student-controlled evaluation - a pilot study. Nurse Education Today 1991; 11 (3): 220-224.

- Sconce C, Howard J. Curriculum evaluation a new approach. Nurse Education Today 1992; 14: 280-286.

- Patton MQ. How to Use Qualitative Methods in Evaluation. Sage Publications, USA,1987.

- Patton MQ. 2nd ed. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills,1990.

- Attree M. Evaluating health care education: Issues and methods. Nurse Education Today 2006, 26: 640-646.

- Suhayda R, Miller JM. Optimizing evaluation of nursing education programs. Nurse Educator 2006; 31 (5): 200-206.

- Robson C. Real World Research. A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-Researchers. Blackwell Publishers LTD, UK, 1993.

- Wholey JS. Evaluation and Effective Public Management. Boston MA. Little Brown, 1983.

- Henry GT. Does the Public Have a Role in Evaluation? Surveys and Democratic Discourse. In: Braverman M.,T. Slater J., K. (Eds.) Advances in Survey Research. New Directions for Evaluation. CA: Jossey Bass, San Francisco, 1996.

- Henry GT, Julnes G. Realist Values and Valuation. In: Henry G.,T., Julnes G., & Mark M.,M. (Eds.) Realist Evaluation: An Emerging Theory in Support of Practice. New Directions for Program Evaluation. San Francisco, 1998.

- House ER. Howe KR. Values in Evaluation and Social Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1999.

- Julnes G, Mark MM, Henry GT. Promoting Realism in Evaluation. Realistic Evaluation and the Broader Context. Evaluation 1998; 4 (4): 483-504.

- Shadish W.R. Philosophy of science and the quantitative-qualitative debates: thirteen common errors. Evaluation and Program Planning 1995; 18 (1): 63-75.

- Jantzi J, Austin C. Measuring learning, student engagement, and program effectiveness. A strategic process. Nurse Educator 2005; 30 (2): 69-72.

- Papanoutsos E.,P. Meters of our Era. Crisis ? Philosophy - Art- Education ? People - Humanity. Fillipotis Publication. Athens, 1981. (In Greek).

- Weaver K., Olson J.K. Understanding paradigms used for nursing research. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2006; 53 (4): 459-469.

- Tolson D, McIntosh J, Loftus L, Cormie P. Developing a managed clinical network in palliative care: a realistic evaluation. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2007; 44 (2):183-195.

- Mc Evoy P, Richards D. Critical Realism: a way forward for evaluation research in Nursing? Journal of Advanced Nursing 2003; 43 (4): 411-420.